По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

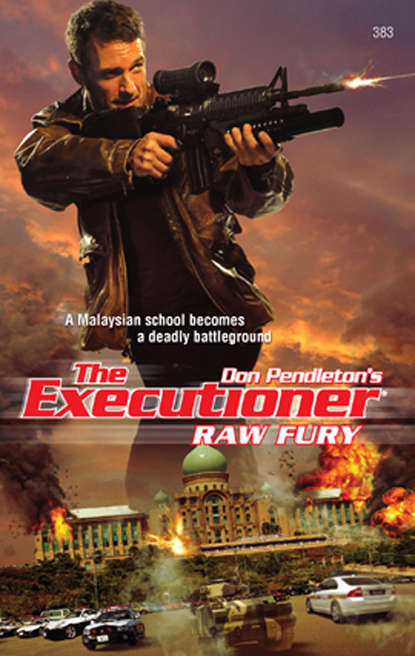

Raw Fury

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“Get in, get in,” the driver said, leaning toward the open passenger window. “Your friend Hal says hello.”

Bolan got into the passenger seat. The taxi growled as the driver put the accelerator to the floor, causing the little car to shudder and buck as it pulled away from the outraged cabbie in the rearview mirror.

“And you are?” Bolan raised an eyebrow as his driver pushed the Hyundai through the dense city traffic, cutting off other drivers with reckless abandon.

“You may call me Rosli,” he said. His English was excellent, with just a hint of an accent. “You are Mr. Cooper, yes?”

“Yes,” Bolan nodded. Matt Cooper was a cover identity he frequently used.

Rosli was of slight build, with a shaved head and a dark complexion. Deep laugh lines made him look older than he probably was. He wore a pair of lightly tinted, round sunglasses, a loose, beige, short-sleeved shirt and a pair of knee-length shorts. Bolan caught a glimpse of his sandaled feet as the man tromped the accelerator for all he was worth.

They drove in silence for a while, Bolan taking in the cityscape. He could see the glass-shelled Petronas Towers in the distance, at one time the tallest buildings in the world. The city was a mix of modern and post-modern architecture, with a healthy dose of nineteenth- and twentieth-century Colonial mixed in.

“I am surprised,” Rosli said finally, “that you are so trusting. I was led to believe you were…a dangerous man. How do you know I am not sent to, what is the word…waylay you?”

“If you were,” Bolan said casually, “I’d kill you, take the wheel and use the curb to bring the car to a stop.”

Rosli opened his mouth to say something, caught something in Bolan’s expression and thought better of it. Finally, he laughed. “Fair enough, Mr. Cooper,” he chuckled. “Fair enough. I do believe you would, too.”

Bolan did not comment.

“We will be at the school within ten minutes, depending on the traffic,” Rosli said, darting around a small panel truck. “There is no time to waste. Your airdrop could not have come too soon.”

“I wouldn’t call a commercial flight an air drop,” Bolan said.

“First class,” Rosli said, “and faster than we could have arranged a charter.”

“Luck,” Bolan said.

“Providence,” Rosli said with a grin. “And therefore the same thing. Regardless, we shall have you in place as quickly as possible, which is not soon enough. You will find what you requested under your seat. You will be pleased to see that everything is there. It was not easy. Your request was very specific. Very difficult.”

Bolan nodded. He reached under the passenger seat to retrieve the olive-drab canvas messenger bag hidden there. He put it on his lap, below the level of the passenger-side windowsill, and inspected the contents.

The bag contained a Beretta 93-R machine pistol. There was also a stainless steel .44 Magnum Desert Eagle. A sound-suppressor and a leather shoulder-harness rig for the Beretta, several loaded magazines and a KYDEX inside-the-waistband holster for the Desert Eagle rounded out the bag’s contents. The Executioner checked the action of one pistol, then the other, before loading both weapons and chambering live rounds. He set both guns on his lap.

In one of the outer pockets of the bag, Bolan found a locking stiletto with a six-inch blade. He pocketed the knife and shrugged into the shoulder harness under his shirt, holstering the Beretta and clipping the Desert Eagle in its holster behind his right hip. He slung the bag across his body, where it could hang on his left side.

Rosli had watched all this activity with interest. “You are impressively armed, Mr. Cooper,” he said. “I am told the weapons were test-fired yesterday, and all is in order.”

Bolan again made no comment. Either the guns would work or they wouldn’t. He didn’t like fielding gear untested by him or the Farm’s armorer, John “Cowboy” Kissinger, but there was nothing to be done about it and no time not to do it. Mentally shrugging, he looked at Rosli and inclined his chin. When the Malaysian operative offered nothing, Bolan said, “And you?”

“A revolver, by my belt buckle,” Rosli said, shrugging. “It is enough.”

“It might be,” Bolan said grudgingly. “It might not. That’s going to depend.”

“On what?” Rosli asked.

“Your proximity to me,” the soldier said frankly.

“Ah.” Rosli nodded, grinning widely through crooked but bright, white teeth. “Yes, that is as your friend Hal warned me it would be.”

Bolan could imagine the exchange the big Fed might have had with Rosli, whom Brognola had described as a CIA asset of some sort, a local boy in long-distance employ of Central Intelligence. Bolan’s own hurried conversation with Hal Brognola had taken place by phone only scant hours before, most of it occurring as Bolan was racing to make the international flight that was, simply by good fortune, scheduled to leave within the half hour. Had Bolan not been concluding some…business…in New York City that put him within a breakneck cab ride to JFK, he’d never have made it. As it was, the hundred dollars he’d tipped the cabbie before the ride had gotten him to the airport with no time to spare despite his near-suicidal driver’s most earnest efforts.

“Striker,” Brognola had said, using Bolan’s code name, “you’re needed in Malaysia. Are you still in New York?”

When Bolan had acknowledged that, yes, he was, Brognola had asked him to catch the nearest cab as fast as he could for the airport, telling the soldier he would explain on the way.

“Okay, you’ve got my attention, Hal,” Bolan had told him, hanging on for all he was worth as his taxi driver burned rubber while weaving in and out of traffic. “I’m on my way.”

“There’s a hostage situation in Kuala Lumpur,” Brognola had explained. “An exclusive private school. It was seized by guerillas today.”

“That sounds bad, Hal—” Bolan nodded, even though the big Fed couldn’t see him and the very focused cabbie couldn’t hear him and wouldn’t care “—but that also sounds like a local problem.”

“It would be,” Brognola said, sounding tired. “But nothing is ever that simple, these days. Have you heard of—” Brognola paused, then recited as if reading from something “—Dato Seri Aswan Fahzal bin Abdul Tuan?”

Bolan blinked. To Brognola, he said, “I can’t say I have.”

“He’s the prime minister of Malaysia,” Brognola said. “Dato Seri is his title. Abdul Tuan was his father, if it matters.”

“So this…Aswan Fahzal, is it?” Bolan said. “What’s his connection?”

“He’s referred to as just Fahzal, usually,” Brognola said. “He swept into power last year amid a flurry of jingoistic fervor, as the media like to call it. His Nationalist Party has some pretty nasty overtones. ‘Malaysia for Malaysians,’ that kind of thing.”

“Understood,” Bolan said, his jaw clenching slightly.

“Well, Fahzal’s government has been putting pressure on Malaysia’s ethnic Indian and Chinese populations, of which there are significant numbers,” Brognola continued. “It started slowly and was initially dismissed as caste-system politics or simple government favoritism. When it got worse, people started to complain, in the United Nations and on the international grassroots scene. I know the folks involved tried to get the attention of Amnesty International, among others.”

“Did they?” Bolan asked.

“Not to the satisfaction of a very vicious few, apparently,” Brognola said. “A new and violent Malaysian rebel group has risen up over the last, oh, six months. The members call themselves what translates roughly to something like, ‘Birth Rights.’ The Farm tagged the group ‘BR’ for simplicity’s sake, because a few of the international terrorist-tracking groups call it that. The Malaysian government has taken to calling it that, too, for the sake of convenience, if nothing else, at least when they refer to it in English. I couldn’t say about the Malay translation.”

“I’m with you so far,” Bolan said.

“BR has claimed responsibility for taking and holding the school,” Brognola said. “If history is any guide, this will not end well. BR may claim to have noble goals, but its members have shown themselves to be terrorists. They’ve staged dozens of actions over the past few months, and in each case, innocents have died, and died hard. Lots of those have been children. BR likes to target young people to make the parents pay. It hasn’t hit the international news because Fahzal’s government has covered it up, suppressed it in the local media, but word has filtered out through other channels.”

“You said BR has taken a school.”

“I did. Among the VIPs who have children in that school is the prime minister himself. His son, Jawan, was the explicit target of the rebel action. They’ve threatened to kill him, not to mention the other students, if Fahzal does not publicly repudiate the Nationalist Party’s agenda and then publicly step down. The crisis has been dragging on, with the terrorists periodically issuing demands. But, while the threat against Fahzal’s son is in force, the government won’t send anyone in to break the stalemate. The terrorists are dug in but good and there’s no telling what defenses they’ve rigged on-site. The longer the standoff goes, the greater the chances that it will end with something deadly on a massive scale. Something’s got to be done to break it.”

“You know I don’t like to see that kind of thing,” Bolan acknowledged, “but I still don’t see what our involvement is. It still sounds like something for the locals to work out for themselves.”

“As I said, it would be,” Brognola told him, “if not for Malaysia’s somewhat delicate diplomatic involvement in Southeast Asia.”

“And that is?” Bolan asked.

“For all its faults internally,” Brognola said, “Fahzal’s government has been a very strong one. Malaysia is doing well economically and, until now, the nation has been very stable. Malaysia’s neighbors are anything but stable at the moment. Border tensions between Thailand and Cambodia are threatening to spill over into Burma and further destabilize that country, which is having its own problems getting along with its rival and neighbor, Bangladesh. Fahzal’s government has extended feelers to both Burma and Bangladesh to see if it can help mediate the dispute, and they’ve been asked, not for the first time, to play diplomatic go-between for the Thais and Cambodians. As far as we can tell, it’s working, too. Fahzal’s diplomatic corps has managed to get all the parties to their respective tables for a series of premeeting confabs, ironing out the ground rules for the eventual peace talks.”

“What does Fahzal get from all of that?” Bolan asked.