По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

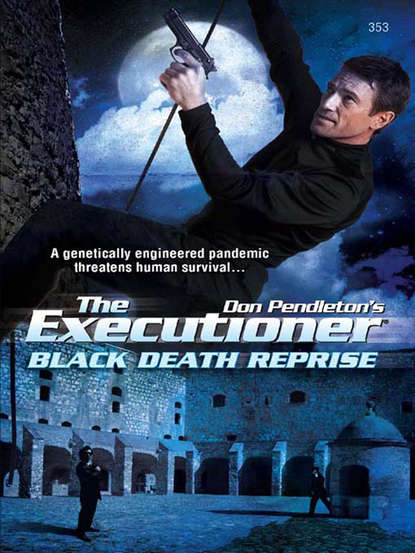

Black Death Reprise

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

In addition to their submachine guns, the sentries wore shoulder holsters carrying FN Five-seveNs. Weighing a mere 1.6 pounds, the Belgium-made pistol used the same 5.7 mm ammunition as the P-90, fed from a clip holding twenty rounds. Although the lightweight handguns lacked the punch that a 9 mm Glock or a Smith & Wesson .45 might deliver, its bullets were available in a version with steel-hardened tips that penetrated Kevlar, making them the ideal choice when anticipating an assault by law-enforcement personnel.

Pulling his goggles over his eyes in order to see the pockets of infrared security placed randomly around the monastery’s perimeter, Bolan inched away from the helipad. The natural foliage was plenty thick to provide good concealment, but it was also short, forcing him to circle the building by alternating between a low crawl and half-crouched sprints until he came to the side he had selected ahead of time from the satellite photos.

In person, the side wall was exactly what he expected. It was close enough to the woods to enable a swift approach, and angled in a way that placed it out of sight from the driveways leading to the front and rear entrances. Most importantly, a window approximately sixty feet off the ground, which Bolan believed was the lab’s only escape route, gleamed brightly against the cold stone walls under the enhanced ambient moonlight created by the goggles. Dropping to one knee, he scanned the wall and area directly beneath, ensuring there were no infrared sensors.

From one of the pouches on his web belt, he withdrew a folding titanium grappling hook tied to a coiled length of thin cord resembling braided dental floss. Developed at NASA by the same team responsible for giving the world Velcro, a three-hundred-foot length was fine enough to fold entirely into the palm of his hand while possessing all the strength of mountaineering rope.

After locking the grappling tines into their open position so they formed a claw resembling an eagle’s talons, Bolan stepped from the woods. While walking toward the building, he began swinging the hook in an increasing arc above his head, playing out the line until he felt the proper tug. When the twine started vibrating slightly in response to the pull exerted by the hook’s momentum, he twirled and snapped his wrist with the finesse of an accomplished fly fisherman, releasing the grappling hook onto a trajectory that sent it sailing over the two-hundred-foot-high wall more than thirty feet to the left of the lab window. Using a hand-over-hand motion to pull in the slack, he found that the hook had caught purchase on his first try.

Before scaling the building, Bolan pushed the goggles onto his forehead where he’d be able to pull them quickly into place if needed. He checked his watch. Two patrolling guards were due to make their rounds within ten minutes, but if they stayed true to the schedule Homeland Security had recorded throughout the previous three weeks of satellite flyovers, Bolan had plenty of time to make his ascent.

Drawing the Beretta from his shoulder holster, he checked the sound suppressor while making sure the safety was off. With one hand, he placed the pistol under the strap holding his knife sheath in place on his outer calf where it would be readily accessible. With the other, he grabbed the thin cord and pulled with all his weight. The line remained taut, and after taking a moment to secure the rest of his gear, he began walking up the side of the fortress like a human fly.

The wall was rough, with thick mortar seams and uneven joints making it easy to climb. As Bolan moved higher, he looped the line around his left hand and elbow, taking in the slack his ascent created.

The assault occurred at approximately seventy feet above ground, when a colony of between ten and fifteen short-nosed fruit bats, apparently attracted by the supersonic whine emanating from Bolan’s infrared goggles, attacked as if they were a school of airborne piranha. With a frantic fluttering of papery wings accompanied by barely audible squeaks, the furry mammals zeroed in on the soldier’s face and neck, biting and scratching with tiny claws as they sought the source of the offending noise.

Wrapping the scaling cord tightly around his left hand in order to free his right, Bolan planted his feet onto the wall and leaned away until he was parallel to the ground. The extended position shifted his entire weight onto his left forearm, causing the tendons to stand out like steel cables stretched to the point of snapping. While reaching up with his freed right hand to switch the goggles’ power switch to the off position, he swatted the bats away from his face and head. Once the goggles were turned off, the colony departed as abruptly as they had arrived, leaving Bolan hanging straight out at a right angle from the rock wall.

An image flashed through his mind of a previous mission conducted years earlier in the tropical jungles of Guatemala when his five-man task force had been attacked by a similar colony of short-nosed bats. Assuming that most wild bats were rabid, the men who had been bitten were afraid they were destined to die a horrible death until one of them who had studied the animals ensured the group that the species’ reputation was undeserved.

Bolan knew bats had a relatively low probability of carrying rabies, much less than for other mammals such as raccoons or skunks. And when the disease did strike, it would wipe out an entire colony within weeks, limiting the communicable danger to a very narrow time period.

As he pulled on the scaling cord to bring himself into a more upright posture, Bolan knew that the guards he suddenly heard coming around the corner of the north parapet posed a much greater threat to his life than the bites and scratches that stung his face and neck in a dozen places.

Upon hearing the sentries, Bolan immediately stopped reeling himself into the wall, halting when he was still at a forty-five-degree angle to the rough surface. Moving in ultra-slow motion, he drew his Beretta 93-R from the strap holding his knife sheath in place and waited for the men below to pass by.

Since he was unable to use his goggles, Bolan couldn’t get a good look at the guards, but from the sounds reaching his ears, he thought they were walking with rifles slung behind their shoulders. The play in the metal clasp where a sling attached to a weapon’s stock created a distinctive click he had heard thousands of times coming from soldiers with their weapons carried at sling arms.

As they approached his position, he tracked them with his 93-R, hoping they would pass without incident. Not that the combat veteran was adverse to killing them both if they so much as looked up—countless corpses littering hellfire trails across the globe were testament to his willingness to survive at all costs—but Bolan found no pleasure in taking life. He was a quintessential soldier, willing to answer the call of duty as defined by his personal values, but he would not kill cavalierly. Despite a career testifying to the contrary, he held a deep respect for the sanctity of life.

The guards were progressing at a steady pace that would bring them directly below his spot in less than a minute. They were speaking softly in French, their tone and cadence causing Bolan to think they were reciting scripture. Beneath his feet, he could suddenly feel a section of the ancient mortar begin to shift under the burden of his angled weight, sending tiny pieces of centuries-old limestone trickling noisily down the wall.

The men looked up, and appearing as if they were performing a synchronized move they had rehearsed a thousand times, grabbed to pull the rifles off their shoulders.

Bolan’s Beretta coughed twice within the span of a second.

The first round caught a guard square in his upturned face, delivering 9 mm Parabellum lead that jerked his head back while lifting him entirely off his feet. He landed two or three yards away, dead before his body impacted the ground.

His partner was hit in the neck, the force of the steel-jacketed slug spinning him in a graceful pirouette while his severed carotid artery sprayed a crimson geyser, making him resemble for a few moments a pulsating lawn sprinkler. As he crumpled to the ground, his heart pumped four or five progressively smaller spurts, which, under the moonlight, took on a rich black hue.

Bolan slid swiftly down the line, intent on hiding the bodies. He knew his entry would eventually be discovered and he’d be forced to fight his way out, but the longer his presence and his point of access remained unknown, the better his chances for getting away with Dr. Zagorski. When he reached the ground, he dragged the corpses into the woods where he arranged them out of sight behind a clump of elms.

A passing cloud cleared the face of the moon, and in the improved light, an oddity caught Bolan’s eye. Both guards possessed what appeared to be identical diamond-shaped scars about the size of a dime on the back of their left hands, the rough tissue standing out in the silvery moonlight against the smoother neighboring skin. As he turned away from the bodies to resume his entry, the soldier filed the detail into a corner of his mind.

Without the encumbrance of the bats, Bolan’s second attempt to scale the wall went quickly. There was no barrier at the top, and he easily pulled himself over the turret’s lip with one arm. Although none of the satellite photos he had studied contained evidence of a roof patrol, Bolan held his Beretta 93-R in his free hand as he came over the parapet, landing softly on the roof’s pebbly surface. When he was sure he was alone, he retrieved the grappling hook and pushed it into its pouch, laying the bunched cord on top.

Occupying the same footprint as the building it capped, the roof’s area was large. Air pumps and condensers for heating systems were arranged in groups interspaced among communication antennas across the top of the ancient building, indicating various heating and communication zones within. Moving in a crouch to reduce his silhouette, Bolan walked straight to the northwest corner, where a series of unique vents and ductwork characteristic of research laboratories sprouted in the shadow of huge air conditioning units like wild orchards on the floor of a redwood forest. Although the air intake tunnel was large enough for a man to enter, a heavy metal grate had been spot-welded across the opening.

From a pouch on his web belt next to where he carried two M-18 smoke canisters, Bolan withdrew a roll of incendiary tape and a small plastic tube containing a substance like petroleum jelly. Using his combat knife, he cut short sections from the half-inch roll and wound them around each of the dozen crossbeams where the grate was welded to the tunnel’s frame. The tape’s active ingredient was a waxy allotrope of white phosphorous that CIA scientists had altered to prevent its reaction to atmospheric oxygen, thus making it a portable product. They had also developed a reagent designed to eliminate the dense white smoke white phosphorous usually produced while burning, which in addition to being undesirably visible, also contained toxic amounts of both phosphorous pentoxide and phosphoric acid.

Once the tape was in place, Bolan used his combat knife to slice open one end of the tube and quickly smear a dollop of the reagent onto each piece. The goop was a sodium-based oxidant that would react in about a minute with the white phosphorous in the tape, bringing it to its flash point.

Once the tape was coated, Bolan averted his eyes and stood close to the grate in an attempt to shield the flashes. The tape buzzed briefly before bursting into a white-hot exothermic flame, each section of tape igniting in the order Bolan had applied the reactant. The burn-through was quick, less than five seconds, but it had taken slightly longer than fifteen to touch every section, which meant the light intensity peaked at seven seconds for a three-second period before dimming. When the tape wrapping the final crossbeam winked out, Bolan dropped to one knee, drawing his handguns. After remaining motionless for slightly longer than a minute, he concluded that the light from the burning white phosphorous had not been seen.

Holstering both his Desert Eagle and Beretta, he grasped the grate in the middle of its grid and pulled it away from the air vent. Before he climbed into the metal tunnel, he adjusted the night goggles over his eyes and switched the unit into IR mode. Seeing no infrared beams blocking his way, he moved headfirst into the vent.

As he progressed through the air tunnel, Bolan recalled the schematic Akira Tokaido had created on the bank of Cray SV2 supercomputers housed at Stony Man Farm. Using sonar data downloaded from satellite flyovers, the talented hacker had been able to produce a three-dimensional map charting air tunnels from the roof leading into the research lab.

“IT’S KIND OF LIKE AN echocardiogram,” Akira Tokaido had told Bolan while nodding slightly to the rhythm of rock music blasting through his ever present earbuds, “just not as accurate.”

“But you’re sure these vents lead into the lab?”

“Not exactly, Striker,” Aaron “The Bear” Kurtzman, head of the cybernetics team at Stony Man Farm had answered for his subordinate. “We have good photos of the roof. There’s no question these are not general air conditioning or heating inlets. We’re assuming they must be laboratory exhaust and intake. For the type of research Dr. Zagorski does, you’d want a dedicated air system. These fit the bill. We believe those vents lead into the lab.”

Using advanced computer modeling to enhance the sonar data stream echoed back to satellite transducers, Tokaido had also drawn a rough floor plan of the second story.

“There’s a stand-alone suite next to where I think the lab is,” he said, tracing with his finger the path Bolan would follow through the air tunnel from the roof to the second floor. He snapped his bubble gum a few times in quick succession before adding, “Private bathroom. Porcelain has a great sonar signature.”

On missions too numerous to count, Bolan had bet his life on the accuracy of information provided by Stony Man Farm. There was no reason for him to start doubting Aaron Kurtzman’s team now.

2

On hands and knees, Bolan moved swiftly through the pitch-black vent, reaching the first intersection at roughly the spot where Tokaido’s diagram had indicated it would be. The air system’s intersecting branches came together between floors, meaning Bolan was already past the third, and directly above the second story where the lab was located. When he came to the T in the tunnel he remembered was close to the end, he removed the goggles and put them away, confident there were no IR sensors in the vent. Although he had engaged enemies on many occasions while wearing night-vision gear, the view in IR mode occasionally shimmered and stalled for a split second when the gallium arsenide photocathode tubes refreshed. For that reason, Bolan avoided using them when he thought gunfire was imminent.

From his shirt pocket, he pulled a powerful penlight, switched it on, and, holding it between his front teeth, turned into the vent’s left branch. Ahead he could see the outline of an access door Tokaido had told him he thought opened onto a stairwell directly next to the lab. It was the spot where Bolan planned to enter the building proper.

Upon reaching the door, he found it was neither secured nor grated, enabling him to turn the latch from the inside and swing the hatch open. Dropping silently onto the landing, he switched off and put away the penlight, and while walking to the stairwell entrance, drew his Beretta 93-R. Taking a deep breath, he turned the knob with his free hand and opened the door on silent hinges.

A wide hallway with a shiny white linoleum floor stretched the entire length of the second floor, dimly illuminated by track lighting running along the ceiling. On both sides of the corridor, two or three doors were located at various points on otherwise blank windowless walls. One was guarded.

Approximately ten yards away, two men dressed in gray jumpsuits were sitting outside a door on which a security slot similar to those used for hotel rooms was mounted above the latch. As he stepped into the hallway, Bolan’s mind registered two critical facts—each man was wearing a lanyard with a magnetic key card clipped to the end and, within easy reach, two Herstal P-90 submachine guns with thirty-round banana clips extending from their ammo ports leaned against the wall. Before Bolan had progressed three steps, one of the men lunged for his weapon.

The Beretta 93-R whispered instant death, delivering a 9 mm Parabellum round that slammed into the side of the man’s face before exiting through the back of his skull in a rush of brain tissue and blood that sprayed a fan-shaped pattern of pink droplets onto the white linoleum. The other guard, apparently realizing that the intruder held a lethal advantage, raised his hands over his head and gazed at Bolan with calm eyes.

He was young, perhaps in his late twenties, with pale blue eyes and a pockmark in the middle of his forehead. Across his right cheek, a deep maroon port-wine stain ran from his temple to the line of his jaw.

“Do you speak English?” Bolan asked.

“Oui. Yes.”

“Where’s Dr. Zagorski?” Bolan asked.

The man’s eyes shifted for a split second in answer to the question before he replied, “I don’t know.”

“Are you ready to die?”

“Yes,” the young man said.