По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

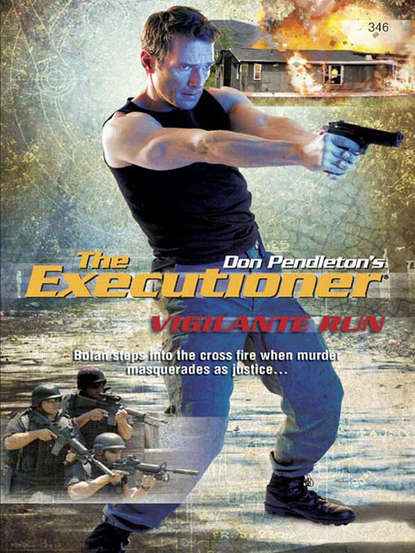

Vigilante Run

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Price stared at the blank screen for a moment before turning to examine the incoming data. There was work to be done.

Camillus, New York

T HE E XECUTIONER LEANED against the black-and-white Syracuse police car, his arms folded across his chest. He’d spent a long night telling and retelling his story, doing his best to wear out the Justice credentials Brognola had provided in the name of Agent Matt Cooper. Now he was simply waiting for the all clear so he could resume his work.

The delay was annoying, but necessary. He would need the cooperation of local law enforcement, and he needed to know who the federal players were. In addition, making himself known might shake loose whomever Brognola’s source believed was cooperating with the murderer or murderers Bolan sought. If he made a big enough target of himself, it was a sure bet someone would take a crack at him to get him out of the way.

At least three government agencies were represented—DEA, FBI and ATF—while the county sheriff’s office and two neighboring police districts had sent units, as well. Bolan had waited patiently while they worked through their histrionics and exaggerated outrage at his presence. One of the ATF agents had held the Beretta 93-R by two fingers as if examining a venomous snake; the FBI duo had threatened to haul him in for interrogation if his ID and story didn’t hold up. The city and suburban police had steered clear of him but shot him suspicious looks. About the only one of them Bolan didn’t immediately dislike was a rookie named Paglia, who watched him carefully but expressed no emotion. That one had the look of a decent lawman who, if he stayed on the force and kept his wits about him, would go far, Bolan thought. He’d seen the type. He’d seen the opposite, too.

When their phone calls and computer queries came back verifying Cooper’s affiliation with the Justice Department, the squawking had largely stopped. Bolan was, however, obliged to stick around until cleared to leave, if he didn’t want to burn any bridges. The mobile home had long since burned itself out, and the agents and police were busily picking through the smoldering debris.

Officer Paglia, who looked impossibly young to Bolan despite his air of competence, returned to his car to drop off several evidence bags. They contained shell casings and a few other odds and ends. Bolan did not expect any of the departments involved to turn up much of use from the burned wreckage, but there was always a chance.

Paglia also carried with him Bolan’s leather shoulder harness, in which was slung the 93-R and its spare magazines. He handed the harness to Bolan and then, from behind his belt, produced the Desert Eagle. “They say you can have your roscoes back,” Paglia chuckled. “They weren’t too happy about it.”

“I’m surprised they let you take any of the evidence,” Bolan commented, nodding at the agents in their variously lettered windbreakers.

“There’s enough to go around,” Paglia told him. Something caught his eye as he turned from his vehicle. He bent to retrieve a singed and empty cardboard carton. Several more just like it were scattered across the field, hurled there by the explosion. The agents and police officers had been walking on them for most of the night.

“Cold medicine,” he said.

“Pseudoephedrine,” Bolan told him. “It’s a precursor chemical, cooked from the over-the-counter drugs in order to manufacture methamphetamine.”

“Crystal meth,” the cop said. “This is a drug house?”

“It used to be,” Bolan said.

F ROM THE TREE LINE ACROSS the snow-covered field, Gary Rook watched the big man in black collect his things and return to the unmarked Chevy Blazer in which he’d arrived the previous night. Through the powerful scope of the Remington 700, the dark-haired man’s face was clearly visible. Rook did his best to memorize the intruder’s features. He had a feeling they would meet again, soon.

Rook had watched as the commando rolled up and entered the meth lab. There was something very unusual about the interloper. He moved like Rook himself—like a man who knew his way around a battlefield. His armed entry into the trailer was textbook, though Rook could have told him there was no one alive in the trailer.

The big, bearded man smiled through red-orange whiskers. His forearms tightened as he flexed his fingers on the synthetic stock of the Remington. Briefly he had considered putting a .308 slug through the commando’s head, but he’d decided to wait. It was a very informative delay. When the Purists arrived, more or less silently on foot, he assumed they’d walked in from wherever they’d left their vehicles, responding to some desperate call made from within the trailer before Rook had finished dealing with the occupants. He’d written off the newcomer then, only to watch in surprise as the man finished each of the bikers in turn. By the time the cops began to show it was too late to move without alerting them to his presence, so he stayed where he was. He watched as they detained the commando, went through their usual songs and dances, then grudgingly turned loose the man in black. Whoever he was, he had powerful connections to go with the ordnance he was packing.

The commando was rolling out in his SUV. Rook resigned himself to waiting until the police and the Feds cleared out, as well. Then he’d make his way back to his own truck and plan his next strike. He’d steer clear of the man in black if he could. If not, well, that was too bad.

If necessary, Rook would kill him, just like the others.

2

Syracuse, New York

Roger Kohler was a busy man. As CEO and majority shareholder of Diamond Corporation, Kohler shepherded an empire spanning everything from low-income rental properties throughout Syracuse, to paid city parking lots, to a piece of the Salt City’s inner harbor development area. He owned three of New York State’s six largest shopping malls—though not, much to his chagrin, one in the city itself. He was working to change that; he was brokering a deal to build the largest shopping mall yet in the state, on the city’s south side.

The project was not without its detractors. The Supreme Court had done him the favor of ruling that local governments could seize property for private investors if that property could be used to generate more revenue. Ostensibly that was for the “public good.” Whatever the justification, this de facto elimination of private property worked to Kohler’s advantage—or it would, once he got approval to seize a large enough chunk of the city’s southwest quarter. It had been done before. One of Kohler’s competitors, another major property concern, had successfully muscled out two dozen established businesses in the city to erect a high-priced luxury hotel that had yet to turn a profit. With that precedent set, Kohler expected only token resistance to his new mall. If legitimate companies could be shown the door in the name of higher tax revenues, who would care about a handful of drug addicts and gang members living in the city’s biggest slum?

Listen to any radio or television newscast in Syracuse and the words “There was a shooting today” or “There was a stabbing today” would be immediately followed by the phrase “on the south side.” Every American city had such a place, if not more than one—an overwhelmingly poor ghetto wherein most of the local crime and the criminals committing it could be found. What better place to clear away for dynamic economic development, for commerce? Kohler couldn’t imagine why everyone in the city didn’t embrace the idea.

There was squawking from the local activist groups, of course. These included wealthy liberals consumed with guilt about their own success, neighborhood sign-wavers belonging to political action and protest organizations, and a scattered few local politicians who had refused to join Kohler’s unofficial payroll. They wouldn’t stop him. Those who couldn’t be marginalized or ignored could simply be eliminated. Kohler maintained certain “business contacts” for that purpose.

Those were not the only problems. There were those who said the city’s depressed economy—the natural outcome of a state whose taxes consistently ranked it among the highest in the nation—couldn’t support such a large project. They didn’t see the opportunities for tourism that Kohler and Diamond promised. They didn’t see the sales tax revenues his consumer and community development center offered. There were those who claimed the city was still reeling from his competitor’s failure to successfully implement the competitor’s own pie-in-the-sky dreams of consumer paradise.

It didn’t help that the failed project—a tremendous mall expansion included absurd plans for everything from a water park and amusement center to a monorail linking the expanded facility to downtown Syracuse—was irrevocably coupled in the minds of locals to a series of bizarre publicity stunts.

Kohler had himself helped sink the project to make way for his own plans, though he regretted just how well it had worked. His own operatives had signed on for the supposed jobs that were created during the project’s opening stages, doing everything from enforcing mall curfew policies to cleaning up area subsidized homes in a bid to perform community service busywork. He made sure that his operatives were among those kept most discreetly in his employ—those who had criminal records. Then he leaked the records to the local newspaper, whose editorial board gleefully reported both the busywork and the felonies. The resulting public relations nightmare put an end to Kohler’s competitor’s dream of revitalizing the city. That left Kohler in what was supposed to have been the perfect position to take up the slack.

The problem was that Kohler’s own project was losing money every day and didn’t seem likely to break even once ground was broken and construction started. The business plan simply wasn’t viable, and Kohler knew it. He could not and would not accept failure, however. That left him with only one option—supplementing his business plan off the books with income from another source.

Kohler was a realist. He had no family. He had no gods. He had only one goal, and that was to enrich himself. He was perfectly at ease with this fact. If it meant he had to consort with a certain class of people, so be it. They were necessary as long as they were useful. They were also easily removed once they stopped being useful.

It was with this thought in mind that Kohler told his secretary to admit Gerald “Pick” McWilliams. It was extremely unusual for Mr. McWilliams to show his face in the Kohler Towers. It was, in fact, forbidden, as far as Kohler was concerned. Only a matter of extreme urgency could bring McWilliams here. Only the severity of Kohler’s financial situation prompted him to permit such an intrusion.

McWilliams came dressed in a thrift store tweed suit that was at least a size too large for him, complete with a polyester tie as thick as a scarf that had to have dated back to the 1970s. The secretary admitted him without a word, and McWilliams almost managed to restrain a leer. Under other circumstances, Kohler would have had trouble blaming the man, as he’d hired Lori specifically to look good. She was blond, she looked great in a tight white blouse, and she never wore skirts longer than midcalf. She was even a passable typist. Mostly, however, she simply guarded the portal to Kohler’s domain and impressed anyone who came calling.

“Pick,” Kohler said without preamble, “what the hell are you doing here?”

McWilliams was a mouse of a man, thin and gaunt, missing a few teeth and suffering from questionable personal hygiene. He was Kohler’s go-between to the CNY Purists, a crude but effective local gang that had proved to be very useful in the less legal aspects of Diamond’s operations. McWilliams was easily intimidated, which was why Kohler tolerated him.

Roger Kohler was formidable enough in his own right. He stood three inches over six feet tall and had the thick build to show for the hours spent in his private gymnasium. He was also a third-degree black belt in karate, the knuckles of his hands scarred and thick from punching bricks and breaking boards. Though his silver hair was growing sparse, Kohler’s granite-hard features left no doubt that he was a man in his physical prime who had no qualms about crushing anyone who got in his way. Kohler permitted himself the visual fantasy of throwing an edge-of-hand strike into McWilliams’s throat simply for being beneath him.

“Mr. Kohler, sir.” McWilliams practically bowed and scraped as he spoke. “There’s a…a problem with the shipment.”

“A problem.”

“Yes, sir.”

“With the shipment.”

“Yes, sir,” McWilliams confirmed again.

“Would you mind telling me, Pick, just what the fuck I pay you people for? ”

Kohler came around from behind the desk, grabbing McWilliams by his wide lapels. “You and your friends have exactly one job to do, and that is to see that the product reaches Ithaca by Sunday! You have exactly five days to meet that deadline. If you do not, we have a serious problem. I will most certainly kill you, but I will have to get in line behind the Chinese and I’ll have to do it before they kill me! ”

“It’s not my fault!” McWilliams whined, making no attempt to protect himself as Kohler shook him like a dog worrying a chew toy. “They hit the cook house we were using. All the product’s gone and the place was blown to shit! We lost a lot of guys, man. You don’t know!”

Kohler paused and released McWilliams, straightening his own suit as he took a deep breath. “That,” he told McWilliams, “is precisely why I pay you and your fellow miscreants. These things happen. Straighten it out. Have a turf war, or something. Do whatever it is you people do. I don’t care who you have to kill. Just do it. Make the problem go away and make damned sure the shipment is all there, on time, by Sunday. Otherwise I swear I’ll break every bone in your body before Chang and his people get to me. ”

McWilliams nodded so hard that Kohler thought the unctuous little man’s head might snap off. The middleman scuttled away without another word, leaving Kohler to consider his empty office, his empty bank accounts and his very full schedule. He decided, then and there, that outside help was in order. He paused to bring up a few relevant files on his computer, including everything he had on McWilliams and his key associates. Then he accessed several of his confidential files. If the Purists couldn’t get the job done, he would bring in someone who could.

While he was at it, he’d see to it that McWilliams was erased simply for annoying him one time too many. McWilliams’s medical records contained an interesting fact. He’d pass that along in the spirit of cooperation. With luck, his new consultant could speed up the process and Kohler could get his business ventures back on track all the sooner.

Despite what he’d told McWilliams, he knew it was unlikely they’d make Chang’s shipment deadline. Given that, he’d have to make alternate arrangements, and given Chang’s difficult temperament, he’d have to make them himself.

Kohler sighed.

It was so hard to get good help these days.

Armory Square, Syracuse