По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

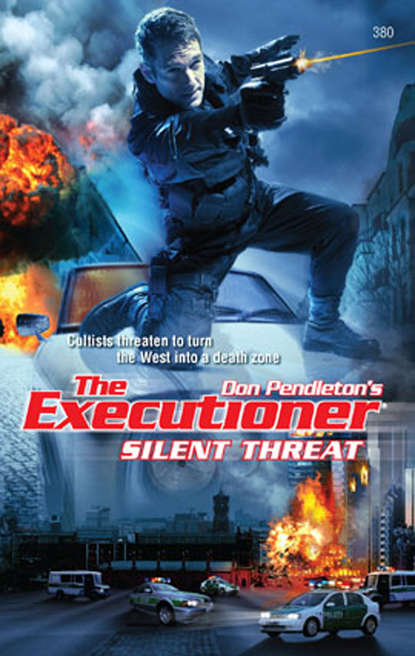

Silent Threat

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Bolan went prone, rolling into position under the middle of his car. He placed the Beretta on the pavement and aimed the Desert Eagle with both hands, targeting the retreating, then running men. These would be difficult shots.

There was no better marksman than the Executioner.

The first .44 slug caught the trailing shooter in the ankle. He screamed and fell, rolling on the wet pavement. The MP-5 was still in his fists, so Bolan dealt him a shot to the head.

The soldier’s third bullet caught the middle runner in mid-calf. He folded over without a sound, almost somersaulting as he lost his footing. Bolan could hear his skull crack on the pavement.

Bolan’s fourth bullet took the farthest gunner in one thigh. He stumbled and nearly fell, but somehow managed to keep moving. The momentary crouch was all the Executioner needed. He snapped another long-distance shot into the man’s head. The body hit the sidewalk on the far side of the street, a crumpled heap beside a storm drain.

Rieck popped up and brought the Uzi forward. He stalked ahead, just a few steps at a time, scanning the surrounding area. Bolan did the same, watching his side while the Interpol agent covered the other. They moved around the cars once, then again, checking to make sure all of the new shooters had been taken.

“Clear!” Rieck called.

“Clear,” Bolan stated. He checked once more, then reloaded and holstered the Desert Eagle. The Beretta 93-R he reloaded but kept at the ready.

“Start checking bodies,” he instructed Rieck. “I’ll see if we’ve got any live ones.” Specifically, he was interested in the gunner who’d hit his head. It was possible he was still alive. Bolan checked the other two first, confirming they were dead, then knelt next to the man in question. He fingered the neck for a pulse and then rolled the body over.

The man stared back, eyes lifeless and glassy. Bolan could tell from the angle the head lolled that the shooter had broken his neck in the fall. Bolan swore. He’d hoped for a live enemy to interrogate, but that couldn’t be helped. Searching through the man’s pockets, he found an extra magazine for the MP-5 in the suit jacket. There was also a fixed-blade fighting knife strapped inside the dead man’s waistband at the small of his back. He carried nothing else. No identification. Bolan left the knife where it was and stood. Rieck was quietly and efficiently going through the other dead men’s pockets.

In the distance, the seesaw foghorn of German police sirens could be heard. The legitimate German authorities were responding, either to Rieck’s calls or to the sounds of gunfire. Bolan saw civilians, bystanders, poking their heads out from behind improvised cover: a man behind a kiosk here, a woman with two small children, out late, hiding in a doorway there. Keeping these people from the cross fire was the primary reason he had brought hell to the enemy, yet again.

Rieck looked mildly wild-eyed. He shucked the empties from his Smith & Wesson—a .357 Magnum, Bolan noted—and popped in a speedloader of fresh rounds.

“Did you find anything?” he asked.

“No.” Bolan shook his head. “You?”

Rieck held out a single laminated ID card. It bore credentials in German, with a photo ID. The name Sicherheit Vereinigung.

“The Security Consortium.” Bolan looked up at Rieck.

“Do you think those three in the shop—”

“No,” Bolan said. “Not likely, anyway.”

“I don’t understand what happened,” Rieck said. “First those three in the shop, and then this group.”

“Assassins,” Bolan said. “That much is obvious. The first three were amateurs. Vicious, but amateurs. These—” he nodded to the bodies of the shooters from the Mercedes “—are professionals. The Consortium sent its hired guns after you. Somebody wants you dead, Rieck.”

“But how? And why?”

“You had to have been followed,” Bolan said.

“I could believe I was followed by those three kids,” Rieck said. “They’d blend in easily enough. But three kids and a parade of Mercedes sedans full of professional soldiers? I may not have your experience, Cooper, but I’m not that stupid.”

“All right.” Bolan nodded. “These Consortium shooters’ involvement remains an unknown. But suddenly you’re very popular.”

“How do you know it was me, and not you?”

“Well,” Bolan said, “you’re the only person locally who even knew to meet me. I find it hard to believe my mission has been blown completely so quickly. That girl with the Uzi targeted you first, too.”

“You saw that?”

“I see everything,” Bolan said dismissively. “That’s not the point. Those ‘kids’ were obviously after you, so they must have been following you, unless someone else knew where we’d be meeting. It’s the only logical answer.”

“No,” Rieck said. “I picked the shop myself and had your people relay it. I assume you trust them and their communications?”

“Absolutely,” Bolan said. There was no way his secure satellite phone or Stony Man Farm’s scrambled up- and downlinks could be compromised, at least at this stage of the game. If the Consortium already knew he was here, and where to find him, the mission was over before it had started. He didn’t think that likely, though he’d been party to plenty of operations in which everything that could go wrong had.

“Did anyone else at Interpol locally know to whom you’d been assigned, or why?” Bolan asked.

“A few,” Rieck admitted. “I’d hate to think we have a leak in the agency.”

“You might,” Bolan said. “That, too, is the simplest explanation.”

“Well, we’ll see about that,” Rieck said. “Once they’ve been checked by the medics we’ll get those two women across the table in an interrogation room and see if we can get them to tell us anything.” They had reached the front of the coffee shop. Rieck put his hand out, swinging the door open.

He stopped. Somewhere in the corner of the shop, one of the witnesses was sobbing. Another man began to protest loudly in German. Bolan didn’t know the words, but he knew the tone: Hey, man, it wasn’t me, I didn’t do anything.

“Jesus,” Rieck said. The toe of his shoe was red with blood.

Bolan pushed past him and checked first one, then the other prisoner. He didn’t blame the bystanders for not interfering. Chances were, they’d been unaware of precisely what they were seeing until it was too late. Only a few minutes’ inattention, while Bolan and Rieck were contending with the new shooters, was all the captured shooters had needed. The two women had pushed themselves together on the floor, presumably after the blonde had regained consciousness. Then the two of them had evidently opened each other’s necks…with their teeth.

“Sweet mother of…” Rieck muttered. “Cooper, what could inspire such an act?”

Bolan looked down at the two dead women, adding the ghastly scene to the too-long catalog in his mind.

“Are they?” Rieck asked.

“Yeah,” Bolan said. “They are.”

The sirens outside grew louder. Rieck checked, his hand on his gun, ready for anything. “The police and two ambulances. Too late for them, I guess.” He nodded to the dead women.

Bolan shook his head. He’d seen plenty of fanatics willing to kill or die for their cause. Call it a gut instinct, but these women didn’t seem to be the type to take their lives for an abstract slogan. No, rather than a cause, rather than a vague “what,” this type of brutal self-sacrifice was most often, in Bolan’s experience, committed for a “who.”

So Rieck’s question stood. They’d have to answer it, too, because it was central to the battle they now fought. This force, this entity, this malevolent being, stood at the center of the maelstrom of violence now threatening to storm across Germany. They needed to know, sooner rather than later.

Just who could inspire this kind of bloodshed?

3

The man known to followers worldwide as Dumar Eon leaned back in his swiveling office chair, steepling his fingers as he stared out the grimy window to the rain-soaked nighttime streets of Berlin. The distant traffic, its rattle and roar incessant and rhythmic, was like a heartbeat. Often he listened to the city, this delightfully sick, this terminally ill city, and fancied he would be there on the day that Berlin’s heart stopped forever.

The austere and immaculately clean office was incongruous in the otherwise decrepit building it occupied. This was the heart of the worst, most crime-ridden, most crumbling section of Berlin’s Neukölln neighborhood. Dumar Eon had heard of Neukölln referred to as a “dynamic” and even “vibrant” suburb, and he supposed there were portions of it that could be considered that. The Neukölln he knew, however, was considerably more deadly than anyone might see written up in real estate periodicals.

Eon stood and went to the window, which was covered with dust. The rain and the headlights of passing vehicles on the narrow streets all but obscured the view, but he peered out placidly as if he could see every crack in the mortar of the surrounding structures. The vaguely L-shaped building, a throwback to the older European architecture of this part of the neighborhood, squatted miserably on a bustling corner, boarded windows like broken or missing teeth marring its otherwise graffiti-covered facade.

The heavy walnut desk that dominated the room was worth more than the building itself, he imagined. It was covered with multiple flat-screen monitors, not to mention a webcam and microphone. Behind the desk, centered in the webcam’s frame, was the black-and-white banner of Iron Thunder: a sledgehammer and a stylized chainsaw in white silhouette on the black field. Thus did the ranks of Iron Thunder smash and clear-cut all those who stood in their way, all those who refused to accept their message. Dumar Eon was well aware that the iconography was slightly less than timeless, but that didn’t matter. Iron Thunder was a religion for today, for the technology of today, and like a shark, it would have to keep moving forward if it wasn’t to die.