По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

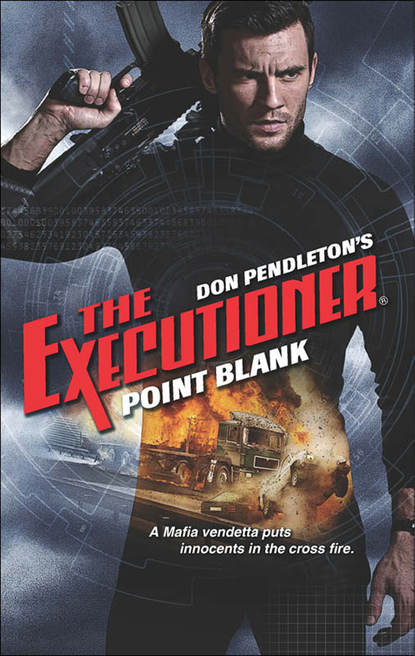

Point Blank

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The game was on in earnest now. And there was going to be blood.

Chapter 2 (#ulink_66e5e005-57aa-5fba-a9f9-96b0df4b0104)

Monday—National Museum of Crime & Punishment, Washington, D.C.

This has to be a joke, Bolan thought. But Hal Brognola, who worked at the U.S. Department of Justice, had proposed the meeting place, so Bolan handed some bills to a clerk behind the sales counter. He cleared the turnstile and passed through a mock medieval dungeon filled with torture devices into a room where a 1930s-era car sat behind velvet ropes, its windows and its paint job shot to hell.

Bolan ignored the serial killers gallery, slack-jawed faces watching him from eight-by-ten mug shots as he walked by. Hal had suggested meeting at the mob exhibit, and he saw it up ahead. More mug shots and blow-ups of newspaper clippings, an Uzi submachine gun next to a fedora and a photo of the neon sign from the original Flamingo hotel and casino, erected by Bugsy Siegel in Las Vegas. Bolan found the display more in tune with Hollywood’s portrayal of the underworld than anything he’d faced in real life.

Hal Brognola suddenly appeared at his elbow. “Let’s take a walk.”

They left gangland behind and ambled toward the museum’s CSI lab, where a mannequin lay on an operating table. Behind it stood displays on toxicology, dental I.D. procedures and the like.

“This must be like a busman’s holiday for you,” Brognola said.

“It cost me twenty-one ninety-five.”

“I get a discount with my badge.”

“Congratulations.”

“So, what do you know about the ’Ndrangheta?” Hal asked, cutting to the chase.

“One of the top syndicates in Italy,” Bolan replied. “Sometimes they collaborate with the Camorra and the Mafia. When that breaks down, they fight. They’re less well known than the Mafia but just as dangerous.”

“And not confined to Italy these days,” Brognola said. “They’re everywhere in Europe, east and west. They’ve also started cropping up in Canada, the States, down into Mexico, Colombia and Argentina. Hell, they’re even in Australia. Worldwide, we estimate they’re banking close to fifty billion annually. Much of that derives from trafficking in drugs. The rest, you name it: weapons, vice, loan-sharking and extortion, public contracts and so-called legitimate business.”

Nothing Hal had said so far was a surprise. Bolan walked beside him, letting him get to the point in his own good time.

“Two days ago, there was a shootout on Shelter Island. Well, a massacre’s more like it. Did you catch the news?”

“Some marshals and a witness,” Bolan said.

“Affirmative. Four deputy U.S. Marshals blown away while watching over one Rinaldo Natale, scheduled to testify next week in New York at the racketeering trial of three high-ranking ’ndranghetisti. Without him, let’s just say the prosecution’s sweating.”

“The time to call would’ve been before Natale bit the dust,” Bolan observed.

“Agreed. But spilled milk and all that. Anyway, we need to send a message back to the Old Country.”

“You know who gave the order?”

“Ninety-nine percent sure I do.”

“Okay,” Bolan said. “Tell me.”

“He’s Gianni Magolino, the capobastone of one of the strongest, if not the strongest, ‘ndrina families in the area.”

“I’m with you so far.”

“His lieutenants are the men awaiting trial in Manhattan.”

“So he has a solid foothold in the States?” Bolan asked.

“Aside from New York, he’s got people in Florida, Nevada, Southern California—and El Paso.”

“Ciudad Juárez,” Bolan replied.

“No doubt.”

The border city, with its countless unsolved murders, was a major gateway for narcotics passing out of Mexico and through El Paso, Texas.

“Any chance of working with the locals in Calabria?” Bolan asked, feeling fairly sure he already knew the answer to his question.

“You know how they are,” Brognola replied. “All good intentions on the surface, and a few hard-chargers in the ranks, but they get weeded out. Their DIA—the anti-Mafia investigators—has had a couple of its top men operating underground for fifteen, twenty years, but no one’s gotten close to Magolino so far.”

“Okay,” Bolan said. “So, I guess you need me out there yesterday.”

“Tomorrow’s soon enough.” Brognola handed him a USB key he’d fished out of a pocket. “Here’s a little homework for the flight.”

* * *

THE TRAVEL PREPARATIONS didn’t take much time. With an afternoon departure from Washington, Bolan made his way to the airport and spent his time there reviewing the information from Hal’s flash drive.

It turned out that the ’Ndrangheta had been operating since the 1860s. Its structure was similar to that of the Mafia, with strong emphasis on family and faith. The sons of members were christened at birth as giovane d’onore, “youth of honor,” expected to follow in their fathers’ footsteps. At age fourteen they graduated to picciotto d’onore—“children of honor”—indoctrinated into blind obedience and tasked with jobs considered “child’s play.” The next rung up the ladder, camorrista, brought more serious duties. Sgarrista was the highest rank of the ’Ndrangheta’s Società Minore and was as far as some members ever advanced.

The next step—into the Società Maggiore—made the member a Santista, or “saint,” the first degree of full membership. Above the saints stood vangelo—“gospels”—quartino, trequartino and padrino. Padrino was the Godfather. Bolan realized much of the ceremony was simply for show. The ’ndranghetisti made a mockery of Italy’s traditional religion and the values normally ascribed to family. For all their talk of sins against the family and stained honor, members of the ’Ndrangheta lived by a savage code of silence enforced by murder. They were no different than any other criminal or terrorist Bolan had confronted in the past, and they deserved no mercy from the Executioner.

Bolan turned his attention to the Magolino family in Catanzaro. Its padrino for the past ten years was one Gianni Magolino, forty-six years old. He had logged his first arrest in 1985, at age seventeen, for attempted murder—a charge dismissed after the victim and four witnesses refused to testify. From there, his rap sheet read like a menu of crime: armed robbery, extortion, aggravated assault, suspicion of drug trafficking, suspicion of gun-running and suspicion of murder (three counts). The only charge that stuck was one for operating an illegal casino. In that case, Magolino had served sixty days and paid a fine of ten thousand lira—about seven American dollars.

That kind of wrist-slap had taught Magolino that crime did pay. He’d clawed his way up to command the former Iamonte family, aided by longtime friend and current trequartino, Aldo Adamo. Four years Magolino’s junior and as ruthless as they came, Adamo was suspected by authorities of more than forty homicides. Most of his victims had been rival ’ndranghetisti, but the list also included two former girlfriends, a cousin and his stepfather. Adamo knew where the bodies were buried, and he’d planted some of them himself.

Together, Magolino and Adamo presided over an estimated four hundred soldiers, with outposts in Spain, Belgium, London, the United States and Mexico. Hal’s digging had turned up a list of friendly coppers in Calabria’s police along with suspected collaborators inside the Guardia di Finanza, a military corps attached to the Ministry of Economy and Finance charged with conducting anti-Mafia operations.

One rotten apple in that barrel could alert ’ndranghetisti to impending prosecutions and allow them to tamper with state’s evidence and mark potential witnesses for execution. Multiply that rotten apple by a dozen or a hundred, and it came as no surprise when top-flight mobsters walked away from court unscathed, time after time.

But living through a Bolan blitz was something else entirely.

As the Maglioni organization was about to learn.

Bolan would be traveling to Italy as Scott Parker, a businessman from Baltimore with diverse interests in petroleum, real estate and information technology. His passport was impeccable, as was the Maryland driver’s license, Platinum American Express card and the matching Platinum Visa. Any background check on “Parker” would reveal two years of military service in his teens, a B.A. in business administration from UM-Baltimore and a solid stock portfolio. As CEO of Parker International, he had the time and wherewithal to travel as he pleased, for business and for pleasure.

This would not be Bolan’s first trip to Italy, by any means. Even before his public “death” in New York City, while Brognola’s Stony Man project was still on the drawing board, Bolan had paid a hellfire visit to Sicily, ancestral home of the Mafia, reminding its godfathers that they were not untouchable. Since then, he’d been back several times, pursuing different angles in the war on terrorism but returning now brought on a flashback to old times.

It never failed. A mention of the Mafia, or any of the syndicates that mimicked it under other names, brought back the nightmare that had devastated Bolan’s family and launched him into a crusade he’d never imagined as a young man. Bolan had been a Green Beret, on track to a distinguished lifer’s career in the military, when he’d lost three-quarters of his family, only his younger brother still alive to tell a tale of murder-suicide provoked by vicious loan sharks. Bolan—already tagged as “The Executioner” for his cold eye and steady hand in battle—had settled that score, then decided personal vengeance fell short of the mark. A whole class of parasites still fed on society’s blood.

Old times, bad times—but what had changed?

Bolan was not religious, in the normal sense. He didn’t shun the notion of a higher power or discount any particular creed at a glance, but if he’d learned one thing from a lifetime of struggle, it was that predators never relented. They might “find the Lord” to impress a parole board, but once they hit the streets again, 99.99 percent reverted to their old ways.