По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

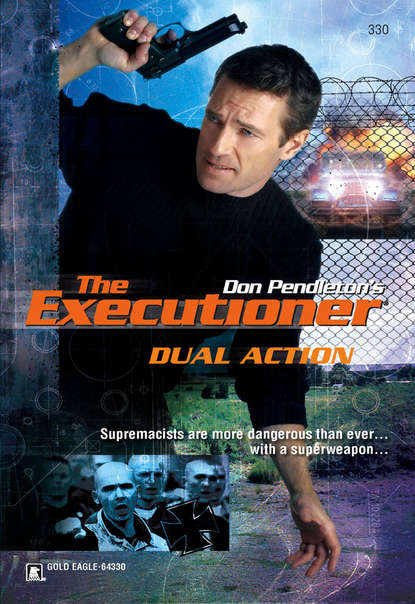

Dual Action

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

2

Two days earlier

A coded-access steel door barred them from the War Room at Stony Man Farm. Barbara Price keyed in her access code, then crossed the threshold as the heavy door slid open. Mack Bolan followed, heard the door shut behind him as he scanned the conference table for familiar faces.

Hal Brognola sat at the head of the table, flanked by Aaron Kurtzman in a wheelchair on his left, two empty chairs immediately on his right for Price and Bolan. Next to Kurtzman, facing one of the empties, sat Huntington Wethers, an African/American cybernetics specialist who’d been lured to the Farm team from a full professorship at Berkeley.

Bolan nodded all around in lieu of handshakes, took his seat and answered the usual small talk about his flight. Even with the chitchat still in progress, he could see Brognola stewing, anxious to be on about the business that had brought them all together.

“We’ve been saddled with a problem,” Brognola began, as if the team had ever been assembled to receive good news.

“I’m listening,” Bolan replied.

“Maybe you heard about the tank incident in Baghdad a few months ago?”

Bolan frowned. “Specifics?”

“An Abrams tank was on routine patrol when it was hit by something that burned through the side skirts and armor on one side, grazed the gunner’s flack jacket and sliced through the back of his seat, then drilled a pencil-sized hole almost two inches deep into the four-inch armor on the turret’s other side. No projectile was recovered. Officially, the incident remains unexplained.”

“And unofficially?” Bolan asked.

“The Pentagon’s as worried as hell. They don’t know what they’re dealing with, who’s got it, how many are out there—in short, they don’t know a damned thing.”

“A secret weapon,” Bolan said. “Each war produces innovations and surprises. Put the SEALs or Special Forces on it. Shake things up. They’ll find a guy who knows a guy and track it down.”

“No luck with that so far,” Kurtzman said. “Top priority or otherwise, they’re pumping dry holes over there.”

“One logical alternative,” Bolan replied, “is a defective weapon of some kind. Guerrillas mix and match. Sometimes they fabricate to meet their needs. New weapons frequently have unpredictable results when they’re first used in combat. Maybe your hotshot was a mistake, and they’ve worked out the bugs.”

“We don’t think so,” Brognola said.

“Why not?”

“Because it’s surfaced in the States.”

Bolan leaned forward in his chair. “Say what?”

“On Wednesday morning, in Ohio,” the big Fed confirmed. “There’s no mistake.”

“Go on.”

“Somebody hit an armored truck en route from Dayton to Columbus, carrying 65 million dollars. Somebody fired twice through the back doors with the supergun—whatever. Cooked the guard back there and spooked the driver, so he rolled it. After that, they used conventional C-4 to pop the doors, iced the witnesses, then made off with the cash.”

“That’s all we have?” Bolan asked.

“Not quite,” Brognola said. “The guards up front got off a radio alarm about the hit. An old gray van, they said, and ‘something weird,’ which pretty much describes the supergun. A couple of state troopers saw the van and started a pursuit.”

“I’m guessing that they didn’t catch it,” Bolan said.

“You’re right. The fugitives lit up a gasoline truck, killed the driver, forced the troopers off the highway, set the fields on fire.”

“The troopers?” Bolan asked.

“One of them’s in a Cincinnati burn ward as we speak. The other didn’t make it.”

“What about the van?”

“Stolen out of St. Louis two weeks earlier,” Brognola said. “Painted and overhauled. They torched it outside Louisville, Kentucky. Wiped out anything forensically significant, but they left stolen license plates from Little Rock, and we could still see how they modified the van inside.”

“Is that significant?” Bolan asked.

“Absolutely,” Wethers interjected. “First, they built a swivel unit where the backseat used to be, then ditched the shotgun seat and fixed the windshield so the right-hand side would lower on a hinge.”

“To fire the supergun,” Bolan said.

“In our estimation, yes. With the arrangement we discovered, they could aim it fore or aft. They made it mobile, and it served them well.”

“Too bad we don’t know who they are,” Bolan remarked.

“I just might have a lead on that,” Brognola said. “It isn’t definite, by any means, but—”

“Give me what you have,” the Executioner replied.

“How much do you know about Christian Identity?” Brognola asked.

“A neo-Nazi version of King James. The Nordic tribes of Israel. Jews are demons, nonwhites are mud people, the usual racist garbage.”

“That’s it, in a nutshell,” Brognola said, “with the emphasis on nuts. It used to be the creed of choice with white supremacists until the 1990s, when a lot of them turned Odinist to claim their Viking roots. The hard core hanging with Identity is more extreme than ever now, maybe to balance what they lost in numbers.”

“If you want to call that balanced,” Wethers said.

“In any case,” Brognola said, forging ahead, “we’ve got a clique of suspects who line up with the events in question geographically. Are you familiar with an outfit called the Aryan Resistance Movement?”

“Not offhand,” Bolan replied.

“Aaron?”

Kurtzman keyed a button from his chair, and Bolan watched a screen descend behind Brognola. From the far wall opposite, a slide projector hummed to life, projecting a map of the central U.S. on the screen. Brognola half turned in his chair to eye the map, as he continued speaking.

“They’re a neo-Nazi outfit, as you might imagine from the name. Still clinging to Identity theology, against the far-right trend. They have a compound here.” He pointed to the northeastern corner of Arkansas with an infrared beam. “You’ll find their background information in the file I brought you, but to summarize, they started in Missouri, then moved south, and they’ve been getting more extreme—more militant—as time goes by. Nonsense about the call to topple ZOG, and so on.”

“That’s the Zionist Occupation Government,’” Barbara Price reminded him. “Otherwise known as the U.S. of A.”

Bolan nodded, familiar with the term from other contacts on the fascist fringe. He waited for Brognola to continue.

“Anyway,” Brognola said, “geography.” The pointer danced across the broad projected map as he continued. “Here we’ve got the ARM, holed up in what they call Camp Yahweh. A hundred miles to the southwest is Little Rock, source of the stolen license plates. Due north, St. Louis, where the movement got its start—”

“And where the van was stolen,” Bolan finished for him.