По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

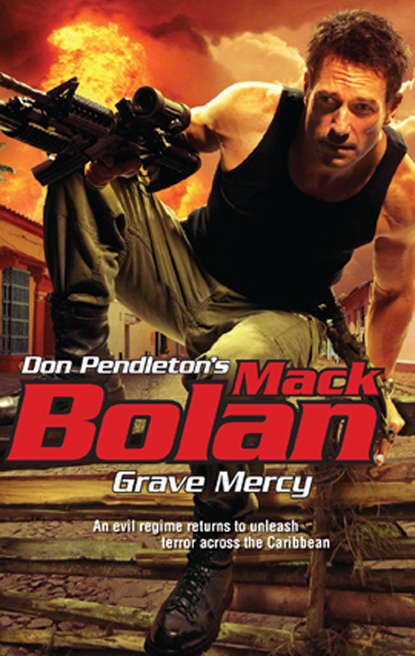

Grave Mercy

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

And that’s when the tall man on the surfboard did something Morrot had never expected—he charged a machete-wielding berserker without even pausing to pull the knife from its calf sheath. In moments, the black-haired surfer had flattened Rojas and turned his attention to one of the women.

All told, the savage squad he’d released onto the Spaulding Youth Surf Camp had been eliminated in the space of two minutes by a single combatant. There were wounded, there were dead, but one lone human had stood against five people whose nerves had been numbed to pain and whose strength had been boosted by chemical-induced ferocity.

“Should we turn the other group back?” Pierre Fortescue asked, watching the same video feed on a monitor of his own.

Morrot shook his head. His mismatched eyes were locked on the screen, looking at the man who had stood for only a brief moment over the unconscious form of the woman. “There won’t be anyone like him in the resort.”

“Who is he?” Fortescue asked.

Morrot could only see the man from the top down, but his shoulders were broad, and his arms were long and wrapped in corded cables of muscle. He was of European descent, despite the darkened tan of his skin. “That man is a professional soldier.”

Fortescue glared at the shaman, but subdued his spite before Morrot took notice. Fortescue himself was the son of one of the strongmen in the old Haitian guard, the Tonton Macoute. The Macoute wasn’t only a cadre of highly trained gunmen, it was backed by ties to superstition and the skills of houngans like Morrot himself. Though Fortescue hadn’t been one of those elite, murderous soldiers, he’d been taught by his father and had sharpened those skills in exile, being a hired gun for various Jamaican gang members.

The implication of Morrot’s words made him bristle, but Fortescue was nothing if not smart. If he’d said or done anything in response to the accusation, Morrot would find a reason and a way to eliminate him. Morrot was ruthless and too damned smart, and Fortescue wasn’t the kind of man to take unnecessary risks. Showing his temper under the one-eyed voodoo priest’s verbal abuse wasn’t just a risk, it was an invitation to slow, painful death after a horrific road of pain and insanity.

“He took down all five. There were a few casualties, but nothing truly usable to increase the panic,” Fortescue said, keeping his voice clinical and cool. “The delivery to the resort will have to bring in some major carnage to instill the proper panic in Kingston.”

“There will be blood and terror,” Morrot told him. “Do not worry, my friend.”

Fortescue looked at the half-mutilated face of the scrawny shaman in front of him. If anyone could manipulate the nations of the Caribbean Sea, it was this dark-hearted wizard of mayhem and madness.

The promise Morrot made would be backed by his programmed-for-madness minions.

WHATEVER GUILT Mack Bolan might have felt at his inability to save lives at the Spaulding Youth Surf Camp was dispelled when he saw that the Pleasant Shore Resort, two miles up the coastal road, had been turned into an abattoir. Dozens were dead, and hundreds injured, many in critical condition. The local news was inundated and trumped by international press circling the Jamaican getaway like sharks now that they had smelled blood in the water, literally.

One of the hotel’s swimming pools had been turned to the color of red wine, the badly mutilated corpses of two people staining what would have been crystal-clear water. The filtration systems were plugged by chunks of flesh, preventing the thinning of the murky pool. The work of five insane people in the resort, armed with machetes that could carve through flesh and bone, was brutally efficient. At the surf camp, their victims had been spread out, giving the Executioner time to intercept the berserkers. The crowds at poolside and on the beach had been caught unaware, and the violent fury released found dozens of targets.

There had been security guards on the scene, but Bolan knew that nothing short of a contact-range shotgun blast or a bullet right in the medulla oblongata would slow the attackers. Handguns were a poor substitute for true fight-stopping firepower, though the Executioner’s skill with his preferred pistols had made him deadly enough to survive combat against opponents with bigger, more powerful guns.

As it was, the security at the resort wasn’t equipped to deal with armed maniacs. It was there to prevent drunks from hurting themselves or harassing the other patrons. The hotels spent big money keeping the drug gangs from bringing their business squabbles into their backyard, and what handguns were available were just that—pistols. The United States military learned a long time ago, during the Moro uprising in the Philippines, the uselessness of a mere sidearm against someone who was on painkillers and in the grip of fanatical rage. The machete-wielding killers would have died from their wounds, but for the fifteen minutes of fury that they were still operating, they were rampaging machines, lashing out at everything.

It had been the Executioner’s training that had carried the day at the surf camp, and even then, there had been casualties. Too many for Bolan’s taste, enough to feel that he’d failed at the standards he’d set for himself. Bystanders were to be protected at all costs, even to the point of catching a bullet in the chest. He’d never staged a battle where civilian noncombatants were on hand, and in instances where others had been endangered, Bolan had done his best to attract attention to himself.

The blood samples that Bolan had collected in water bottles sat in the little humming refrigerator, a box with a door and its sides and front covered in plastic sheeting colored to look like wooden paneling. He’d transfer it to a cooler to take it to a laboratory for examination, but even refrigerated, the blood and the chemicals within weren’t going to last forever. Within twenty-four hours, natural enzyme breakdowns could erase traces of some toxins and drugs. Freezing the blood was an option, but then again, there was the problem of crystallization of water affecting the chemical makeup.

Bolan’s laptop screen flickered to life, an incoming call from Stony Man Farm jarring it from sleep mode. Barbara Price, her face illuminated by her monitor’s bleak, harsh light, appeared in the web camera chat box. She was mission controller at Stony Man Farm, the installation that was home to the nation’s elite antiterrorist teams. Bolan sat in front of his own camera, dressed in a black T-shirt and khaki-colored cargo pants. Price’s eyes flicked left, then right, noting the straps of his shoulder holster in place.

“You’re aware of the attack in the resort,” Price said.

“I caught a preview. It looked like someone wanted to release my marauders into the wild after they tore up a camp full of unarmed surfers and other kids,” Bolan answered.

Price pursed her lips in a frown before speaking again. “You said you’d suffered casualties.”

Bolan didn’t answer.

“Hal and the President have been going over this. They know that you’re in the region, but they aren’t certain that the situation warrants your involvement,” Price said.

Bolan still remained quiet, his slitted eyes providing the only sign of a response, a show of annoyance that the Sensitive Operations Group and the White House were able to dictate where and why the Executioner would take action. He finally spoke. “They don’t have to be. I’m certain.”

Price nodded. “Hal knows better than to deny you your choice of operations.”

“I’ve got refrigerated blood samples from the berserkers I encountered. Is there a lab handy where I can get this looked at?” Bolan asked.

“We’ve been checking local laboratories and most in the country don’t have the kind of toxicology skills you’d need,” Price replied. “But we have help in the area.”

“Hospital ships off Haiti,” Bolan surmised. “U.S. Navy? I don’t want to pull personnel off of the relief effort.”

“No problem in that regard. We have someone on hand who is a trained medic,” Price said.

“Is Cal coming to pick me up himself, or do I meet him on the ship?” Bolan asked.

“A navy helicopter’s coming to get you and the samples to meet him,” Price replied. “Since there’s no need for forensic toxicology, the facilities on board the aircraft carrier devoted to that won’t take away from things.”

“Good,” Bolan returned. “What’s my cover?”

“Colonel Brandon Stone,” Price returned. “We’ve already set it so that you can be armed on the carrier, but you do have to carry concealed.”

Bolan shrugged. “Even military brass can’t be armed on a Navy ship.”

“Not everyone believes in the inherent goodness of the U.S. Armed Forces,” Price replied. “Unfortunately that includes many commanders in the Navy, the Army…”

“I’ll deal with it,” Bolan said, tugging on a BDU overshirt, concealing the Beretta 93-R in its holster. As a soldier in the field, and years of interacting with servicemen abroad, the soldier had learned that the Pentagon policies about disarming troops when not in direct contact with the enemy had lead to countless being left vulnerable to ambushes. The death toll, thanks to those policies, was high, a level of loss that caused suffering among families at home and crippling deficiencies among active-duty personnel.

“The helicopter is coming to the camp, correct?”

“The less you have to travel with the blood before it can be brought to the lab, the better,” Price told him.

Bolan nodded. “ETA?”

“Ten minutes.”

The soldier looked up from buttoning the jacketlike uniform blouse. “I’ll be ready. Any news on who is claiming responsibility for the attack?”

“No word per se,” Price said. “Though the zombie-like rage exhibited by the attackers have people talking about voodoo. Someone leaked videos through the internet and they have hit cable news stations.”

“That may be the point,” Bolan replied.

Price tilted her head. “How so?”

“Phoenix, Able and I have had plenty of encounters with real-life voodoo zombies over the years,” Bolan said, referring to Phoenix Force and Able Team, Stony Man’s two action units. “Some were just makeup and bulletproof vests while others were people whose minds were destroyed by traditional houngan treatments, either as cheap slave labor or purpose constructed.”

Price frowned. “No one is taking responsibility because the targets of this attack will know who was behind it.”

“It could be part of the local Jamaican drug war, trying to fill in the void I recently knocked in the status quo,” Bolan added. “Or it could be something political, because I can’t see the cocaine cowboys on this island making a mess of their target demographic.”

“Tourists looking for nose candy and herb,” Price said.

Bolan nodded. “If they scare off tourism, a lot of their local dealers lose customers. With no income, they can’t bribe the hotels to let them hang around and deal, and the addition of violence in the hotels makes them really out of luck.”