По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

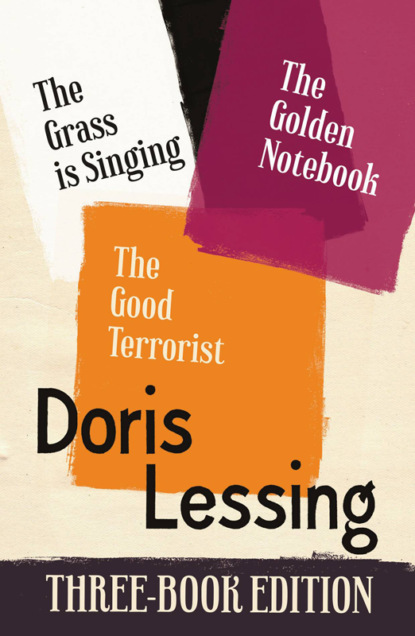

Doris Lessing Three-Book Edition: The Golden Notebook, The Grass is Singing, The Good Terrorist

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

He took his meals with the Turners. Otherwise, he was expected to pick up enough knowledge in a month to keep this place running for six, until Dick returned. He spent all day with Dick on the lands, rising at five, and going to bed at eight. He was interested in everything, well-informed, fresh, alive – a charming companion. Or perhaps Dick might have found him so ten years before. As it was he was not responsive to Tony, who would start a comfortable discussion on miscegenation, perhaps, or the effects of the colour bar on industry only to find Dick staring, with abstract eyes. Dick was concerned, in Tony’s presence, only to get through these last days without losing his last shreds of self-respect by breaking down, by refusing to go. And he knew he had to go. Yet his feelings were so violent, he was in such a turmoil of unhappiness, that he had to restrain crazy impulses to set fire to the long grass and watch the flames destroy the veld he knew so well that each bush and tree was a personal friend; or to pull down the little house he had built with his own hands and lived in so long. It seemed a violation that someone else would give orders here, someone else would farm his soil and perhaps destroy his work.

As for Mary, Tony hardly saw her, He was disturbed by her, when he had time to think about the strange, silent, dried-out woman who seemed as if she had forgotten how to speak. And then, it would appear that she realized she should make an effort, and her manner would become odd and gauche. She would talk for a few moments with a grotesque sprightliness that shocked Tony and made him uncomfortable. Her manner had no relation to what she was saying. She would suddenly break into one of Dick’s slow, patient explanations about a plough or a sick ox, with an irrelevant remark about the food (which Tony found nauseating) or about the heat at this time of the year. ‘I do so like it when the rains come,’ she would say conversationally, giggle a little, and relapse suddenly into a blank, staring silence. Tony began to think she wasn’t quite all there. But then, these two had had a hard time of it, so he understood; and in any case, living here all by themselves for so long was enough to make anyone a bit odd.

The heat in that house was so great that he could not understand how she stood it. Being new to the country he felt the heat badly; but he was glad to be out and away from that tin-roofed oven where the air seemed to coagulate into layers of sticky heat. Although his interest in Mary was limited, it did occur to him to think that she was leaving for a holiday for the first time in years, and that she might be expected to show symptoms of pleasure. She was making no preparations that he could see; never even mentioned it. And Dick, for that matter, did not talk about it either.

About a week before they were due to leave, Dick said to Mary over the lunch table, ‘How about packing?’ She nodded, after two repetitions of the question, but did not reply.

‘You must pack, Mary,’ said Dick gently, in that quiet hopeless voice with which he always addressed her. But when he and Tony returned that night, she had done nothing. When the greasy meal was cleared away, Dick pulled down the boxes and began to do the packing himself. Seeing him at it, she began to help; but before half an hour was gone, she had left him in the bedroom, and was sitting blankly on the sofa.

‘Complete nervous breakdown,’ diagnosed Tony, who was just off to bed. He had the kind of mind that is relieved by putting things into words: the phrase was an apology for Mary; it absolved her from criticism. ‘Complete nervous breakdown’ was something anyone might have; most people did, at some time or another. The next night, too, Dick packed, until everything was ready. ‘Buy yourself some material and make a dress or two,’ said Dick diffidently, for he had realized, handling her things, that she had, almost literally, ‘nothing to wear’. She nodded, and took out of a drawer a length of flowered cotton stuff that had been taken over with the stock from the store. She began to cut it out, then remained still, bent over it, silent, until Dick touched her shoulder and roused her to come to bed. Tony, witness of this scene, refrained from looking at Dick. He was grieved for them both. He had learned to like Dick very much; his feeling for him was sincere and personal. As for Mary, while he was sorry for her, what could be said about a woman who simply wasn’t there? ‘A case for a psychologist,’ he said again, trying to reassure himself. For that matter, Dick would benefit by treatment himself. The man was cracking up, he shivered perpetually, his face was so thin the bone structure showed under the skin. He was not fit to work at all, really; but he insisted on spending every moment of daylight on the fields; he could not bear to leave them when dusk came. Tony had to bring him away; his task now was almost one of a male nurse, and he was beginning to look forward to the Turners’ departure.

Three days before they were due to leave, Tony asked to stay behind for the afternoon, because he was not feeling well. A touch of the sun, perhaps; he had a bad headache, his eyes hurt, and nausea moved in the pit of his stomach. He stayed away from the midday meal, lying in his hut which, though warm enough, was cold compared to that oven of a house. At four o’clock in the afternoon he woke from an uneasy aching sleep, and was very thirsty. The old whisky bottle that was usually filled with drinking water was empty; the boy had forgotten to fill it. Tony went out into the yellow glare to fetch water from the house. The back door was open, and he moved silently, afraid to wake Mary, whom he had been told slept every afternoon. He took a glass from a rack, and wiped it carefully, and went into the living-room for the water. A glazed earthenware filter stood on the shelf that served as a sideboard. Tony lifted the lid and peered in: the dome of the filter was slimy with yellow mud, but the water trickled out of the tap clear, though tasting stale and tepid. He drank, and drank again, and, having filled his bottle, turned to leave. The curtain between this room and the bedroom was drawn back, and he could see in. He was struck motionless by surprise. Mary was sitting on an upended candle-box before the square of mirror nailed on the wall. She was in a garish pink petticoat, and her bony yellow shoulders stuck sharply out of it. Beside her stood Moses, and, as Tony watched, she stood up and held out her arms while the native slipped her dress over them from behind. When she sat down again she shook out her hair from her neck with both hands, with the gesture of a beautiful woman adoring her beauty. Moses was buttoning up the dress; she was looking in the mirror. The attitude of the native was of an indulgent uxoriousness. When he had finished the buttoning, he stood back, and watched the woman brushing her hair. ‘Thank you, Moses,’ she said in a high commanding voice. Then she turned, and said intimately: ‘You had better go now. It is time for the boss to come.’ The native came out of the room. When he saw the white man standing there, staring at him incredulously, he hesitated for a moment and then came straight on, passing him on silent feet, but with a malevolent glare. The malevolence was so strong, that Tony was momentarily afraid. When the native had gone, Tony sat down on a chair, mopped his face which was streaming with the heat, and shook his head to clear it. For his thoughts were conflicting. He had been in the country long enough to be shocked; at the same time his ‘progressiveness’ was deliciously flattered by this evidence of white ruling-class hypocrisy. For in a country where coloured children appear plentifully among the natives wherever a lonely white man is stationed, hypocrisy, as Tony defined it, was the first thing that had struck him on his arrival. But then, he had read enough about psychology to understand the sexual aspect of the colour bar, one of whose foundations is the jealousy of the white man for the superior sexual potency of the native; and he was surprised at one of the guarded, a white woman, so easily evading this barrier. Yet he had met a doctor on the boat coming out, with years of experience in a country district, who had told him he would be surprised to know the number of white women who had relations with black men. Tony felt at the time that he would be surprised; he felt it would be rather like having a relation with an animal, in spite of his ‘progressiveness’.

And then all these considerations went from his mind, and he was left simply with the fact of Mary, this poor twisted woman, who was clearly in the last stages of breakdown, and who was at this moment coming out of the bedroom, one hand still lifted to her hair. And then he felt, at the sight of her face, which was bright and innocent, though with an empty, half-idiotic brightness, that all his suspicions were nonsense.

When she saw him, she stopped dead, and stared at him with fear. Then her face, from being tormented, became slowly blank and indifferent. He could not understand this sudden change. But he said, in a jocular uncomfortable voice: ‘There was once an Empress of Russia who thought so little of her slaves, as human beings, that she used to undress naked in front of them.’ It was from this point of view that he chose to see the affair; the other was too difficult for him.

‘Was there?’ she said doubtfully at last, looking puzzled.

‘Does that native always dress and undress you?’ he asked.

Mary lifted her head sharply, and her eyes became cunning. ‘He has so little to do,’ she said, tossing her head. ‘He must earn his money.’

‘It’s not customary in this country, is it?’ he asked slowly, out of the depths of his complete bewilderment. And he saw, as he spoke, that the phrase ‘this country’, which is like a call to solidarity for most white people, meant nothing to her. For her, there was only the farm; not even that – there was only this house, and what was in it. And he began to understand with a horrified pity, her utter indifference to Dick; she had shut out everything that conflicted with her actions, that would revive the code she had been brought up to follow.

She said suddenly, ‘They said I was not like that, not like that, not like that.’ It was like a gramophone that had got stuck at one point.

‘Not like what?’ he asked blankly.

‘Not like that.’ The phrase was furtive, sly, yet triumphant. God, the woman is mad as a hatter! he said to himself. And then he thought, but is she, is she? She can’t be mad. She doesn’t behave as if she were. She behaves simply as if she lives in a world of her own, where other people’s standards don’t count. She has forgotten what her own people are like. But then, what is madness, but a refuge, a retreating from the world?

Thus the unhappy and bewildered Tony, sitting on his chair beside the water filter, still holding his bottle and glass, staring uneasily at Mary, who began to talk in a sad quiet voice which made him say to himself, as she was speaking, changing his mind again, that she was not mad, at least, not at that moment. It’s a long time since I came here,’ she said, looking straight at him, in appeal. ‘So long I can’t quite remember…I should have left long ago. I don’t know why I didn’t. I don’t know why I came. But things are different. Very different.’ She stopped. Her face was pitiful; her eyes were painful holes in her face. ‘I don’t know anything. I don’t understand. Why is all this happening? I didn’t mean it to happen. But he won’t go away, he won’t go away.’ And then, in a different voice, she snapped at him, ‘Why did you come here? It was all right before you came.’ She burst into tears, moaning, ‘He won’t go away.’

Tony rose to go to her: now his only emotion was pity; his discomfort was forgotten. Something made him turn. In the doorway stood the boy, Moses, looking at them both, his face wickedly malevolent.

‘Go away,’ said Tony, ‘go away at once.’ He put his arm round Mary’s shoulders, for she was shrinking away and digging her fingers into his flesh.

‘Go away,’ she said suddenly, over his shoulder at the native. Tony realized that she was trying to assert herself: she was using his presence there as a shield in a fight to get back a command she had lost. And she was speaking like a child challenging a grown-up person.

‘Madame want me to go?’ said the boy quietly.

‘Yes, go away.’

‘Madame want me to go because of this boss?’

It was not the words in themselves that made Tony rise to his feet and stride to the door, but the way in which they were spoken. ‘Get out,’ he said, half-choked with anger. ‘Get out before I kick you out.’

After a long, slow, evil look the native went. Then he came back. Speaking past Tony, ignoring him, he said to Mary, ‘Madame is leaving this farm, yes?’

‘Yes,’ said Mary faintly.

‘Madame never coming back?’

‘No, no, no,’ she cried out.

‘And is this boss going too?’

‘No,’ she screamed. ‘Go away.’

‘Will you go?’ shouted Tony. He could have killed this native: he wanted to take him by his throat and squeeze the life out of him. And then Moses vanished. They heard him walk across the kitchen and out of the back door. The house was empty. Mary sobbed, her head on her arms. ‘He’s gone,’ she cried, ‘he’s gone, he’s gone!’ Her voice was hysterical with relief. And then she suddenly pushed him away, stood in front of him like a mad woman, and hissed, ‘You sent him away! He’ll never come back! It was all right till you came!’ And she collapsed in a storm of tears. Tony sat there, his arm round her, comforting her. He was wondering only, ‘What shall I say to Turner?’ But what could he say? The whole thing was better left. The man was half-crazy with worry as it was. It would be cruel to say anything to him – and in any case, in two days both of them would be gone from the farm.

He decided that he would take Dick aside and suggest, only, that the native should be dismissed at once.

But Moses did not return. He was not there that evening at all. Tony heard Dick ask where the native was, and her answer that she ‘had sent him away’. He heard the blank indifference of her voice: saw that she was speaking to Dick without seeing him.

Tony, at last, shrugged in despair, and decided to do nothing. And the next morning he was off to the lands as usual. It was the last day; there was a great deal to do.

11 (#ulink_5fc75be8-3094-52bf-b6c4-03db8686db47)

Mary awoke suddenly, as if some big elbow had nudged her. It was still night. Dick lay asleep beside her. The window was creaking on its hinges, and when she looked into the square of darkness, she could see stars moving and flashing among the tree boughs. The sky was luminous; but there was an undertone of cold grey; the stars were bright; but with a weak gleam. Inside the room the furniture was growing into light. She could see a glimmer that was the surface of the mirror. Then a cock crowed in the compound, and a dozen shrill voices answered for the dawn. Daylight? Moonlight? Both. Both mingled together, and it would be sunrise in half an hour. She yawned, settled back on her lumpy pillows, and stretched out her limbs. She thought, that usually her wakings were grey and struggling, a reluctant upheaval of her body from the bed’s refuge. Today she was vastly peaceful and rested. Her mind was clear, and her body comfortable. Cradled in ease she locked her hands behind her head and stared at the darkness that held the familiar walls and furniture. Lazily she created the room in imagination, placing each cupboard and chair; then moved beyond the house, hollowing it out of the night in her mind as if her hand cupped it. At last, from a height, she looked down on the building set among the hush – and was filled with a regretful, peaceable tenderness. It seemed as if she were holding that immensely pitiful thing, the farm with its inhabitants, in the hollow of her hand, which curved round it to shut out the gaze of the cruelly critical world. And she felt as if she must weep. She could feel the tears running down her cheeks, which stung rawly, and she put up her fingers to touch the skin. The contact of rough finger with roughened flesh restored her to herself. She continued to cry, but hopelessly for herself, though still from a forgiving distance. Then Dick stirred and woke, sitting up with a jerk. She knew he was turning his head this way and that, in the dark, listening; and she lay quite still. She felt his hand touch her cheek diffidently. But that diffident, apologetic touch annoyed her, and she jerked her head back. ‘What is the matter, Mary?’

‘Nothing,’ she replied.

‘Are you sorry you are leaving?’

The question seemed to her ridiculous; nothing to do with her at all. And she did not want to think of Dick, except with that distant and impersonal pity. Could he not let her live in this last short moment of peace? ‘Go to sleep,’ she said. ‘It’s not morning yet.’

Her voice seemed to him normal; even her rejection of him was too familiar a thing to waken him thoroughly. In a minute he was asleep again, stretched out as if he had never stirred. But now she could not forget him; she knew he was lying there beside her, could feel his limbs sprawled against hers. She raised herself up, feeling bitter against him, who never left her in peace. Always he was there, a torturing reminder of what she had to forget in order to remain herself. She sat up straight, resting her head on locked hands, conscious again, as she had not been for a very long time, of that feeling of strain, as if she were stretched taut between two immovable poles. She rocked herself slowly back and forth, with a dim, mindless movement, trying to sink back into that region of her mind where Dick did not exist. For it had been a choice, if one could call such an inevitable thing a choice, between Dick and the other, and Dick was destroyed long ago. ‘Poor Dick,’ she said tranquilly, at last, from her recovered distance from him; and a flicker of terror touched her, an intimation of that terror which would later engulf her. She knew it: she felt transparent, clairvoyant, containing all things. But not Dick. No; she looked at him, a huddle under blankets, his face a pallid glimmer in the growing dawn. It crept in from the low square of window, and with it came a warm airless breeze. ‘Poor Dick,’ she said, for the last time, and did not think of him again.

She got out of bed and stood by the window. The low sill cut across her thighs. If she bent forward and down, she could touch the ground, which seemed to rise up outside, stretching to the trees. The stars were gone. The sky was colourless and immense. The veld was dim. Everything was on the verge of colour. There was a hint of green in the curve of a leaf, a shine in the sky that was almost blue, and the clear starred outline of the poinsettia flowers suggested the hardness of scarlet.

Slowly, across the sky, spread a marvellous pink flush, and the trees lifted to meet it, becoming tinged with pink; and bending out into the dawn she saw the world had put on the colour and shape. The night was over. When the sun rose, she thought, her moment would be over, this marvellous moment of peace and forgiveness granted her by a forgiving God. She crouched against the sill, cramped and motionless, clutching on to her last remnants of happiness, her mind as clear as the sky itself. But why, this last morning, had she woken peacefully from a good sleep, and not, as usually, from one of those ugly dreams that seemed to carry over into the day, so that there sometimes seemed no division between the horrors of the night and of the day? Why should she be standing there, watching the sunrise, as if the world were being created afresh for her. feeling this wonderful rooted joy? She was inside a bubble of fresh light and colour, of brilliant sound and birdsong. All around the trees were filled with shrilling birds, that sounded her own happiness and chorused it to the sky. As light as a blown feather she left the room and went outside to the verandah. It was so beautiful: so beautiful she could hardly bear the wonderful flushed sky, streaked with red and hazed against the intense blue; the beautiful still trees, with their load of singing birds; the vivid starry poinsettias cutting into the air with jagged scarlet.

The red spread out from the centre of the sky, seemed to tinge the smoke haze over the kopjes, and to light the trees with a hot sulphurous yellow. The world was a miracle of colour, and all for her, all for her! She could have wept with release and lighthearted joy. And then she heard it, the sound she could never bear, the first cicada beginning to shrill somewhere in the trees. It was the sound of the sun itself, and how she hated the sun! It was rising now; there was a sullen red curve behind a black rock, and a beam of hot yellow light shot up into the blue. One after another the cicadas joined the steady shrilling noise, so that now there were no birds to be heard, and that insistent low screaming seemed to her to be the noise of the sun, whirling on its hot core, the sound of the harsh brazen light, the sound of the gathering heat. Her head was beginning to throb, her shoulders to ache. The dull red disc jerked suddenly up over the kopjes, and the colour ebbed from the sky; a lean, sunflattened landscape stretched before her, dun-coloured, brown and olive-green, and the smoke-haze was everywhere, lingering in the trees and obscuring the hills. The sky shut down over her, with thick yellowish walls of smoke growing up to meet it. The world was small, shut in a room of heat and haze and light.

Shuddering, she seemed to wake, looking about her, touching dry lips with her tongue. She was leaning pressed back against the thin brick wall, her hands extended, palms upwards, warding off the day’s coming. She let them fall, moved away from the wall, and looked over her shoulder at where she had been crouching. ‘There,’ she said aloud, ‘it will be there.’ And the sound of her own voice, calm, prophetic, fatal, fell on her ears like a warning. She went indoors, pressing her hands to her head, to evade that evil verandah.

Dick was awake, just pulling on his trousers to go and beat the gong. She stood, waiting for the clanging noise. It came, and with it the terror. Somewhere he stood, listening for the gong that announced the last day. She could see him clearly. He was standing under a tree somewhere, leaning back against it. his eyes fixed on the house, waiting. She knew it. But not yet, she said to herself, it would not be quite yet; she had the day in front of her.

‘Get dressed, Mary,’ said Dick, in a quiet urgent voice. Repeated, it penetrated her brain, and she obediently went into the bedroom and began to put on her clothes. Fumbling for buttons she paused, went to the door, about to call for Moses, who would do up her clothes, hand her the brush, tie up her hair, and take the responsibility for her so that she need not think for herself. Through the curtain she saw Dick and that young man sitting at the table, eating a meal she had not prepared. She remembered that Moses had gone: relief flooded her. She would be alone, alone all day. She could concentrate on the one thing left that mattered to her now. She saw Dick rise, with a grieved face, pull across the curtain; she understood that she had been standing in the doorway in her underclothes, in the full sight of that young man. Shame flushed her; but before the saving resentment could countermand the shame, she forgot Dick and the young man. She finished dressing, slowly, slowly, with long pauses between each movement – for had she not all day? – and at last went outside. The table was littered with dishes; the men had gone off to work. A big dish was caked with thick white grease; she thought that they must have been gone some time.

Listlessly she stacked the plates, carried them into the kitchen, filled the sink with water, and then forgot what she was doing. Standing still, her hands hanging idly, she thought, ‘Somewhere outside, among the trees, he is waiting.’ She rushed about the house in a panic, shutting the doors, and all the windows, and collapsed at last on the sofa, like a hare crouching in a tuft of grass, watching the dogs come nearer. But it was no use waiting now: her mind told her she had all day, until the night came. Again, for a brief space, her brain cleared.

What was it all about? she wondered dully, pressing her fingers against her eyes so that they gushed jets of yellow light. I don’t understand, she said. I don’t understand…The idea of herself, standing above the house, somewhere on an invisible mountain peak, looking down like a judge on his court, returned; but this time without a sense of release. It was a torment to her, in that momentarily pitiless clarity, to see herself. That was how they would see her, when it was all over, as she saw herself now: an angular, ugly, pitiful woman, with nothing left of the life she had been given to use but one thought: that between her and the angry sun was a thin strip of blistering iron; that between her and the fatal darkness was a short strip of daylight. And time taking on the attributes of space, she stood balanced in mid-air, and while she saw Mary Turner rocking in the corner of the sofa, moaning, her fists in her eyes, she saw, too, Mary Turner as she had been, that foolish girl travelling unknowingly to this end. I don’t understand, she said again. I understand nothing. The evil is there, but of what it consists, I do not know. Even the words were not her own. She groaned because of the strain, lifted in puzzled judgement on herself, who was at the same time the judged, knowing only that she was suffering torment beyond description. For the evil was a thing she could feel: had she not lived with it for many years? How many? Long before she had ever come to the farm! Even that girl had known it. But what had she done? And what was it? What had she done? Nothing of her own volition. Step by step, she had come to this, a woman without will, sitting on an old ruined sofa that smelled of dirt, waiting for the night to come that would finish her. And justly – she knew that. But why? Against what had she sinned? The conflict between her judgment on herself, and her feeling of innocence, of having been propelled by something she did not understand, cracked the wholeness of her vision. She lifted her head, with a startled jerk, thinking only that the trees were pressing in round the house, watching, waiting for the night. When she was gone, she thought, this house would be destroyed. It would be killed by the bush, which had always hated it, had always stood around it silently, waiting for the moment when it could advance and cover it, for ever, so that nothing remained. She could see the house, empty, its furnishings rotting. First would come the rats. Already they ran over the rafters at night, their long wiry tails trailing. They would swarm up over the furniture and the walls, gnawing and gutting till nothing was left but brick and iron, and the floors were thick with droppings. And then the beetles: great, black, armoured beetles would crawl in from the veld and lodge in the crevices of the brick. Some were there now, twiddling with their feelers, watching with small painted eyes. And then the rains would break. The sky would lift and clear, and the trees grow lush and distinct, and the air would be shining like water. But at night the rain would drum down on the roof, on and on, endlessly, and the grass would spring up in the space of empty ground about the house, and the bushes would follow, and by the next season creepers would trail over the verandah and pull down the tins of plants, so that they crashed into pullulating masses of wet growth, and geraniums grew side by side with the blackjacks. A branch would nudge through the broken windowpanes, and slowly, slowly, the shoulders of trees would press against the brick, until at last it leaned and crumbled and fell, a hopeless ruin, with sheets of rusting iron resting on the bushes, and under the tin, toads and long wiry worms like rats’ tails, and fat white worms, like slugs. At last the bush would cover the subsiding mass, and there would be nothing left. People would search for the house. They would come across a stone step propped against the trunk of a tree, and say, ‘This must be the Turners’ old house. Funny how quick the bush covers things over once they are left!’ And, scratching round, pushing aside a plant with the point of a shoe, they would come upon a door-handle wedged into the crotch of a stem, or a fragment of china in a silt of pebbles. And, a little further on, there would be a mound of reddish mud, swathed with rotting thatch like the hair of a dead person, which was all that remained of the Englishman’s hut; and beyond that, the heap of rubble that marked the end of the store. The house, the store, the chicken runs, the hut – all gone, nothing left, the bush grown over all! Her mind was filled with green, wet branches, thick wet grass, and thrusting bushes. It snapped shut: the vision was gone.

She raised her head and looked about her. She was sitting in that little room with the tin roof overhead, and the sweat was pouring down her body. With all the windows shut it was unbearable. She ran outside: what was the use of sitting there, just waiting, waiting for the door to open and death to enter? She ran away from the house, across the hard, baked earth where the grains of sand glittered towards the trees. The trees hated her, but she could not stay in the house. She entered them, feeling the shade fall on her flesh, hearing the cicadas all about, shrilling endlessly, insistently. She walked straight into the bush, thinking: ‘I will come across him, and it will all be over.’ She stumbled through swathes of pale grass, and the bushes dragged at her dress. She leaned at last against a tree, her eyes shut, her ears filled with noise, her skin aching. There she remained, waiting, waiting. But the noise was unbearable! She was caught up in a shriek of sound. She opened her eyes again. Straight in front of her was a sapling, its greyish trunk knotted as if it were an old gnarled tree. But they were not knots. Three of those ugly little beetles squatted there, singing away, oblivious of her, of everything, blind to everything but the life-giving sun. She came close to them, staring. Such little beetles to make such an intolerable noise! And she had never seen one before. She realized, suddenly standing there, that all those years she had lived in that house, with the acres of bush all around her, and she had never penetrated into the trees, had never gone off the paths. And for all those years she had listened wearily, through the hot dry months, with her nerves prickling, to that terrible shrilling, and had never seen the beetles who made it. Lifting her eyes she saw she was standing in the full sun, that seemed so low she could reach up a hand and pluck it out of the sky: a big red sun, sullen with smoke. She reached up her hand; it brushed against a cluster of leaves, and something whirred away. With a little moan of horror she ran through the bushes and the grass, away back to the clearing. There she stood still, clutching at her throat.

A native stood there, outside the house. She put her hand to her mouth to stifle a scream. Then she saw it was another native, who held in his hand a piece of paper. He held it as illiterate natives always handle printed paper: as if it is something that might explode in their faces. She went towards him and took it. It said: ‘Shall not be back for lunch. Too busy clearing things up. Send down tea and sandwiches.’ This small reminder from the outer world hardly had the power to rouse her. She thought irritably that here was Dick again; and holding the paper in her hand she went back into the house, opening the windows with an angry jerk. What did the boy mean by not keeping the windows open when she had told him so many times…She looked at the paper; where had it come from? She sat on the sofa, her eyes shut. Through a grey coil of sleep she heard knocking on the door and started up; then she sat down again, trembling, waiting for him to come. The knock sounded again. Wearily she dragged herself up and went to the door. Outside stood the native. ‘What do you want?’ she asked. He indicated, through the door, the paper lying on the table. She remembered that Dick had asked for tea. She made it, filled a whisky bottle with it, and sent the boy away, forgetting all about the sandwiches. The thought was in her mind that the young man would be thirsty; he was not used to the country. The phrase, ‘the country’, which was more of a summons to consciousness than even Dick was, disturbed her, like a memory she did not want to revive. But she continued to think about the youth. She saw him, behind shut lids, with his very young, unmarked, friendly face. He had been kind to her; he had not condemned her. Suddenly she found herself clinging to the thought of him. He would save her! She would wait for him to return. She stood in the doorway looking down over the sweep of sere, dry vlei. Somewhere in the trees he was waiting; somewhere in the vlei was the young man who would come before the night to rescue her. She stared, hardly blinking, into the aching sunlight. But what was the matter with the big land down there, which was always an expanse of dull red at this time of the year? It was covered over with bushes and grass. Panic plucked at her; already, before she was even dead, the bush was conquering the farm, sending its outriders to cover the good red soil with plants and grass; the bush knew she was going to die! But the young man…shutting out everything else she thought of him, with his warm comfort, his protecting arm. She leaned over the verandah wall, breaking off the geraniums, staring at the slopes of bush and vlei for a plume of reddish dust that would show the car was coming. But they no longer had a car; the car had been sold…The strength went out of her, and she sat down, breathless, closing her eyes. When she opened them the light had changed, and the shadows were stretching out in front of the house. The feeling of late afternoon was in the air, and there was a sultry, dusty evening glow, a clanging bell of yellow light that washed in her head like pain. She had been asleep. She had slept through this last day. And perhaps while she slept he had come into the house looking for her? She got to her feet in a rush of defiant courage and marched into the front room. It was empty. But she knew, without any doubt at all, that he had been there while she slept, had peered through the window to see her. The kitchen door was open; that proved it. Perhaps that was what had awakened her, his being there, peering at her, perhaps even reaching out to touch her? She shrank and shivered.