По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

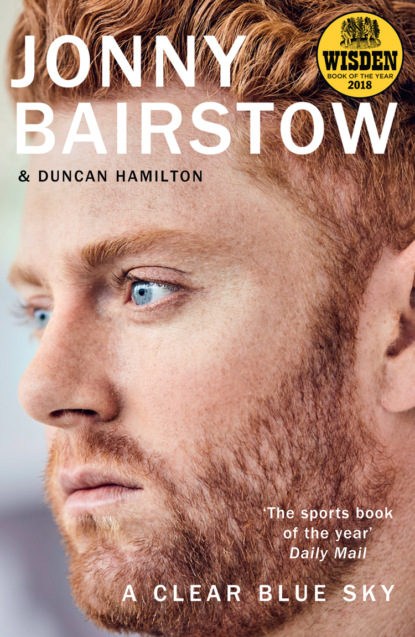

A Clear Blue Sky: A remarkable memoir about family, loss and the will to overcome

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Van Zyl has been put on to remind me of Durban. To lull me into relaxing against him and committing another error. The difference between him and Morkel, who is fielding on the boundary, is as stark as the difference between a light breeze and a lashing wind. Van Zyl sends down innocuous-looking deliveries, the odd one drifting away or cutting back. I’m wary of him purely because of my score. To get from 95 to 99, I filched one single off Morkel and three off Van Zyl. I’m still waiting for the unexpected from him. The Wonder Ball. Something he’s hidden so far. Something that seems nothing in the air but is everything off the pitch – either dipping low, towards my bootstraps, or darting up, forcing me to fend it off.

Like Donald Bradman before him, Brian Lara said he didn’t focus so much on the fielders as on the gaps between them. I’m checking and rechecking the set of the field, looking for the spaces too, so that I’ll know with a nailed-on certainty where to send anything loose. South Africa are tinkering with the field. It’s dragged in before minor adjustments are made – a yard here, a few paces there. It’s an attempt to deprive me of a single and persuade me to hit over the top. This drawn-out process is also an attempt to niggle and make me feel nervous. It won’t. I’m telling myself three things:

Patience … Patience … Patience.

The crowd is pent-up. There’s cheering and hollering and chanting until just before the ball is bowled, when a silence engulfs the ground. It’s as though everyone is holding their breath for me.

It’s the fourth ball of the 118th over. It’s the 161st ball of my innings.

Possibly the heat has wearied Van Zyl. Or possibly he is just a tad too eager to get at me, and the strenuous effort he puts into the delivery throws his stride out, leaving him fractionally off-balance. Whatever the reason, his arm gets dragged down just a sliver as he heaves his body into it. As a batsman, you’re constantly dealing with the infinitesimal. Judgements are made in millimetres and in microseconds. Get any calculation wrong, and you’re likely to perish. Everything happens so quickly, the ball on top of you after a blur and a kerfuffle of movement. In the time it takes to blink you’re working out speed, trajectory and direction. Even someone of Van Zyl’s relatively sedate pace demands that. But I see this ball early. And, almost as soon as it leaves his hand, I know its length and line. I also know which stroke I’ll play – a cut past backward point, a shot I’ve executed in games innumerable times and practised innumerable times more. My dad loved the cut. ‘If they bowl short outside the off stump, it’s bingo,’ he used to say. This is bingo for me too. I go back and across my stumps, ever so slightly crouching. I’m in position, waiting for it before it arrives. This is my moment and I’ve come to meet it.

You know when you’ve hit a good shot. I use a bat that weighs 2 pounds and 9 ounces, and it makes a reassuringly solid sound when I connect properly. The ball pings off the middle. I start to run, but there’s no need. It’s going for four.

The ‘YES’ I scream in response is half roar, half rebel yell. It’s loud enough for someone to hear it in Leeds. I’m still shouting it, and still wearing my helmet, when I lean back, arms outstretched. Then I yank my helmet off, kiss the badge on the front of it and hold my bat aloft. I tilt my head upwards. All I see is the unblemished arch of the sky, clearer and bluer than ever. All I hear is the crowd – the clapping, the cheers, the thunder of voices. What I feel is absolute relief and the profoundest joy. I am experiencing what I can only describe as the sense of complete fulfilment, which is overwhelming me.

I’m so grateful to Ben Stokes. It’s second nature to dash to your partner when he reaches a hundred, sharing the stage with him. Stokesy doesn’t. He stands back, a spectator like everyone else, allowing me a minute alone. He knows. Finally, he throws one of those big, tattooed arms around me and says: ‘Soak it up. Take it all in, mate.’

I do.

And what comes back, of course, crowding into my mind, is the past, which puts everything into context. My dad. My grandpa. My grandma. My mum. My sister. I could weep now. I could let the tears out, but I fight against them instead, closing my eyes to dam them up.

My dad always liked to know where my mum was sitting before he went in to bat. He drew comfort from the fact that she was there and giving her support – even when he couldn’t see her distinctly. At the beginning of his innings he’d search for her from the crease and settled only when he’d fastened on to the approximate location or, better still, actually spotted her in a row, usually because of something she was wearing. I’m exactly the same. I’ll always look in her direction, searching for her face among a thousand others.

My mum is sometimes unable to look when I bat; she might hide in a corridor when I get near a landmark score. I know she’ll have braved this one out, but everyone is standing and applauding so I can’t see her at first. I point with my bat towards where I know for certain she and Becky are sitting, a gesture for them alone.

Eventually the noise of the crowd dies away, and I think of starting my innings again. But first I take one last look at the sky. If heaven has a pub, I hope my dad is in it now. I hope he’s ordering a pint to celebrate.

Then I hope he orders another.

CHAPTER 1

THE VIEW FROM THE VERANDA (#ulink_0626a159-ecb3-5245-90e2-c870136fab66)

First, the bare, stark fact – the matter of public record.

My dad was only 46 years and 126 days old when he committed suicide. My mum, my sister Becky and I found him when we returned home at 8.30 p.m., which was one of those typically lampblack and cold January nights. He had hanged himself from the staircase.

Now, the speculation – the what ifs, the what-might-have-beens, the guesswork.

The great risk of being alive is always that something can happen to you – or to someone you dearly love – at any moment. I learnt that lesson on a Monday evening so ordinary that otherwise it would be indistinguishable from a thousand-and-one others. Everything seemed normal to me. They say that even the sensibilities of infants can pick up a minute shift of mood at home, alerting them when something is a little odd or off. I’d gone past the stage of infancy – I was a young child – but I’d registered nothing untoward. To me, my dad was just my dad, as ebullient and as energetic as ever. I never saw him down or doubtful, or fretful about either himself or our future. I had no inkling that anything was wrong. He didn’t seem like a man full of distractions to me.

In the morning I said goodbye to him and walked to school with Becky, the Christmas holidays over and a new term beginning. In the early evening my mum took me to football training at Leeds United, bringing Becky too. That our lives changed irrevocably while the three of us were away seemed to me – then as well as now – inconceivable and incomprehensible.

The inquest into my dad’s death, which I didn’t attend, heard evidence about his mental state. That he’d been suffering from depression and stress. That he’d seen both his own doctor and a consultant psychiatrist because of it. That he’d experienced extreme mood swings, veering between the dramatically high and the dramatically low, leaving my mum unsure about ‘which version of him would come through the door’. That he’d been for a drink at one of his favourite pubs a few hours before he died (though the toxicology report revealed no extravagant level of alcohol in his system). That he’d been concerned about my mum’s health and the treatment she was undergoing for breast cancer, diagnosed less than three months before and far more aggressive than even she appreciated at the time. She’d undergone chemotherapy, radiotherapy and then chemotherapy again. She was wearing a wig because her hair had fallen out. I didn’t know – but I learnt later – that the hospital became more concerned about my dad’s emotional state than my mum’s. He was afraid she was going to die. He was also afraid of how he would cope – and what would happen to us – if she did.

Also, my dad had been particularly anxious about an impending court appearance to answer a drink-driving charge, which would certainly have meant the loss of his licence, a potentially grievous blow to his promotional and marketing business – and to our family finances. The incident precipitating it was an accident on a quiet country road the previous October. My dad was bringing me home from training at Leeds in his Volkswagen Scirocco. A car, coming in the opposite direction, dazzled him with its headlights, which were unusually bright. For a split second, my dad lost control of the wheel. We veered off the road, struck a slight bank and the car tipped over. The Scirocco ended up on its right side, leaving me on top of my dad.

Shoeless, and still wearing my football kit, I freed myself and then clambered over him, escaping through the back window. With only the odd cut and bruise, which was miraculous, I stood in the middle of the road and waited. The driver who’d blinded my dad hadn’t stopped; he’d sped away, long gone and unidentifiable. A friend of mine, also on Leeds’ books, was being taken home by his father. I flagged them down, and the police and an ambulance were called. That afternoon my dad had been at the funeral of a golfing buddy. Like everyone else, he’d gone to the wake afterwards. The police routinely brought out the breathalyser, finding him over the limit. I can’t condone my dad’s drink-driving, but the circumstances surrounding the case – the car responsible for it, the driver absconding afterwards without a care for our well-being, the fact that my dad hadn’t been speeding – didn’t seem to interest the police. I, the only other witness, wasn’t even asked to give a statement. I am still livid about that.

The repercussions of the crash rippled out. My dad was mortified that he’d put me in danger, mulling over afterwards how much worse the crash could have been. It left him with a debilitating arm injury. His future in local cricket, and also the enormous pleasure he got from playing golf, were both jeopardised. His right arm and shoulder required an operation, and 16 pins and a plate were put in to support his joints, which brought him considerable pain during his ongoing recovery.

Fraught with worry as the court case loomed and his other problems accumulated, my dad had not only been drinking too much generally – and he accepted as much – but a few weeks earlier he had also swallowed an overdose of painkillers at home: the same painkillers that had been prescribed for his injuries. He described taking them as ‘a cry for help’. My mum had for months urged him to go to a doctor and talk openly about his depression. Either he refused or, after giving in and going to an appointment, he threw up a smokescreen for the doctor’s benefit. He pretended there wasn’t anything wrong with him that wouldn’t soon be shaken off. ‘He and the doctor ended up talking mostly about sport,’ my mum said.

The coroner was patient and sympathetic, aware of my dad’s popularity and the accounts of him as a decent family man. He recorded an open verdict, as certain as he could be that my dad hadn’t meant to die. He was making a further ‘cry for help’, and it had gone wrong in a way that he hadn’t foreseen and didn’t intend because his illness confused him and clouded his judgement. My dad, knowing that we were on our way home, thought we would rescue him, added the coroner. As it turned out, one small innocent delay after another – none of them anyone’s fault – meant we arrived back half-an-hour later than we’d planned.

The coroner’s concise, concluding sentence encapsulated the difficulty for those of us left behind looking for closure and searching for The Why behind his death.

‘I do not know what happened,’ the coroner said. ‘He is the only one who did.’

Though almost 20 years have passed, I’m no closer to an explanation for what happened, which makes it harder to accept. Why my dad decided to end his life, and why he did so that evening, is an unsolvable puzzle. There was no note to read, no definitive clue to discover. There were fragments, just bits and pieces of information, but putting them together to reconstruct his last months never created a coherent whole that made absolute sense and explained everything, especially about what he must have been thinking. No matter how hard I tried, from what I knew as I grew up or discovered subsequently, there were always gaping holes. Questions that can’t be answered. Things that don’t add up. The truth is snagged somewhere in between them, caught in one of those places that’s impossible to reach.

I live with that.

The following day was my mum’s 42nd birthday. Only a few hours before he died my dad had gone to a nearby town and booked a celebratory meal for the two of them. He’d also booked a babysitter to look after Becky and me. That act makes what he did seem even more illogical to us than ever. So did something he said not long before. After a friend of his died, also committing suicide by hanging, he’d asked my mum, disbelievingly: ‘Why on earth would anyone do that?’

I suppose I could track down everyone my dad saw or spoke with towards the end, but I’m sure doing so would produce only more contradictions, more confusion. For on the one hand he’d recently told a journalist friend, during a train journey to London, that he was in fine fettle and eager for 1998 to start. ‘I’m at the top of my form,’ he’d insisted. On the other, he’d told Mike Brearley, who had been his England captain, completely the opposite. ‘He felt awful … things were not good,’ reported Brearley.

So, instead of certainties, there are only theories, and always will be. My mum believes there were ‘small bereavements inside him’, among them the loss of his cricket career, his search for something to replace it – which he never found – and also the death of his father. My dad was an only child. His father raised him all but alone after his mother abandoned the two of them. He was only three years old. My dad never saw his mother again, relying on his aunts to offer the maternal care every child needs. When, shortly before she died, his mother wrote and finally wanted to see him, my dad didn’t want to meet her. He was still playing for Yorkshire then. ‘She’s known where I’ve been for the last thirty years and hasn’t bothered to visit,’ he told my mum. ‘I don’t want to hear from her now. It’s too late.’ My mum tried conciliation, telling him: ‘There are always two sides to a story … perhaps she’ll explain why she left and why she hasn’t been in touch since.’ My dad wasn’t interested. One of the most perplexing letters of condolence we received after my dad’s death came with an Australian postmark. The writer, a complete stranger to us, asked my mum to pass on his sympathies to my dad’s ‘brother’. She wrote back explaining that, as far as she knew, my dad didn’t have a brother. If he did, we still don’t know anything about him.

Apart from the hurt and anger that her unexplained absence left simmering in him, perhaps my dad didn’t want to see his mother again because doing so would have been a betrayal of his father. He was christened Leslie, but everyone called him Des after his own father – apart, of course, from my dad, who referred to him as ‘Pops’. He was a smaller version of my dad with bow legs so pronounced that stopping a pig in a passage would have been difficult for him. He was born on the last day of 1916, the year in which the Battle of the Somme claimed more than a million casualties. Some of the killed, maimed and injured belonged to battalions made up of Bradford Pals, including members of the extended Bairstow family. He was given the middle name Somme because of it. He’d played cricket for Laisterdyke, both before and after the Second World War as a wicketkeeper, served overseas in the army and ended his working life in a chemical factory. He was an old-fashioned sort of gent, usually seen carrying a rolled-up newspaper. As a greeting back to anyone who said hello, he’d tap the top of his forehead with the newspaper, a show of northern politeness.

My dad adored his father. Early in his career he would often dedicate a catch, a stumping or an innings to him, telling reporters: ‘Pops will be proud of that.’ The two of them were good companions and each loved and felt indebted to the other. My dad kept a black-and-white photograph of his father in his wallet and put another much larger and colourised version of it on the wall at home. Every year, paying tribute to his father’s military background, he’d wear his poppy proudly and we would attend the Remembrance Day service at Boroughbridge, the town closest to us.

My dad died almost to the day that his own father had died 16 years before. Was that a coincidence? I don’t know; I never will.

Illness does its early work in secret, so another crucial aspect I don’t know is when his own began. My dad once declared ‘I love life’. For so long he gave every indication of doing that, making it impossible to pinpoint precisely when feeling a little down became melancholy and then tipped into an engulfing depression. My dad had suffered a succession of setbacks. He’d applied for the job as Yorkshire’s Cricket Manager, believing he was the ideal candidate. He didn’t get it. He considered standing for the committee until the prospect of success dimmed for him. He’d been doing occasional commentaries for the BBC, and listeners liked him, but a more permanent role went to someone else. He’d been steadily hunting down promotional work, which was becoming harder to get. He’d been running his own company, winning a contract to merchandise World Cup ties.

Life without cricket was initially harder for my dad than playing the game had ever been. He missed it, and also the adrenalin pump of a performance. He missed the crack and the camaraderie of the dressing room eight years after leaving it too. For two decades he’d got himself set for the glad rush of each new summer, and he sincerely believed he had a few more of them left in him. But, when he was 38, Yorkshire nudged him reluctantly into retirement before he was ready or properly prepared for it. He remained convinced, for at least a season or two afterwards, that he was still good enough for the County Championship team. He was almost waiting for Yorkshire to realise this and recall him, which in the beginning made it more difficult to settle into an alternative career. There is nothing he wouldn’t have done for them. His roots were in Yorkshire cricket. So were his inspirations. And so was his identity, his sense of self.

My dad wore the White Rose on his sleeve, the county’s emblem becoming his own. The county was bone and blood and breath to him. He once stood on top of the huge concrete marker post, emblazoned with that White Rose, which tells the traveller on the M62 where Lancashire ends and Yorkshire begins. He wore his full kit, and brandished a bat with his arms flung wide. This wasn’t a pose. Nor was the beaming expression he wore put on for the sake of a good picture. My dad really did believe that Yorkshire was the epicentre of the world.

The Cricketer once ran a headline that said: ‘Bairstow ready to shed tears for Yorkshire’. Shed tears he did – and plenty of them. I’ve reliably heard that he played every match for Yorkshire – even a friendly – as though it was a Test; and also that every defeat was a grievous wound to him. He once said: ‘I took defeat quite badly. I tried not to show how much I cared to the others. More often than not I went for a long brisk walk on my own. I would march along, getting it out of my system … I was better on my own.’ He also admitted that there were ‘times when I feel down, just like everyone else, and then I need others to pat me on the back, crack a joke or two and take the job that I normally do’.

One of his colleagues, John Hampshire, even wrote in my dad’s benefit brochure that he was prone to ‘fits of depression’ when Yorkshire didn’t perform – or when he didn’t perform for them. ‘When this man is down the whole world knows about it,’ he added. After his death, the assessment was plucked out in isolation, over-analysed and misinterpreted. John, one of the nicest men I knew, was talking about the sad low of losing rather than highlighting the medical definition of clinical depression. For when my dad did have the condition, the evidence of how capably he concealed the fact – telling pretty white lies about it – was contained in the shock his suicide created.

A doctor can ask a patient who has a physical pain ‘where does it hurt?’ The patient will point to a specific spot. With a mental illness, it hurts everywhere. During the past decade in particular, we’ve only just begun to understand such a simple fact and take some long and welcome strides towards a more compassionate understanding of it. We’ve also developed an appreciation about the right and wrong ways of discussing and handling mental illness. The language we use when referring to depression has changed. Mercifully gone is the edge of mockery, condescension and flippancy that used to be commonplace. This change was slow in coming, and more change is still needed, but we’ve grown up and matured as a society, realising nowadays that no shame or stigma should ever be attached to the condition.

People in my dad’s day, especially those associated with a macho sport, were wary at best and petrified at worst about coming forward and confessing to a problem. For a man, it wasn’t manly, a situation that seems ridiculous to us now. You could be perceived as weak or written off as damaged goods. That is why my dad disguised his own depression with a façade in those conversations with his doctors. It was a convincing act in which he pretended to be himself, proving again that mental illness can be invisible to the naked eye when the sufferer never complains and presents a pasted-on smile to the world.

At Yorkshire, he’d been given two nicknames. The first was ‘Stanley’, after the Bradford-born writer Stan Barstow, author of A Kind of Loving, one of those popular kitchen-sink novels of the late 1950s and early 1960s. No one quibbled over the missing ‘i’. The second, which he relished, was ‘Bluey’, the slang word Australians use for anyone with red hair. My dad also had eyes that were bright blue, so the name, which John Hampshire gave him, stuck. It fitted him as well as a handmade suit; ‘Bluey Bairstow’ rolled off the tongue. There was something breezy and high-spirited about it that matched his approach to the game as well as to life. ‘After that,’ my dad said, ‘no friend ever called me David again – unless they were telling me off.’

However dreadful he surely felt inside during his bad days, I think my dad strove outwardly to be the Bluey everyone expected – confident, lively and always as full of bonhomie as he could be. The copious newspaper reports of his death, each of the cuttings torn and yellow with age now, show how successfully he maintained the pretence. Fred Trueman found his suicide ‘beyond belief’. Fooled like so many others, Brian Close thought my dad had been his ‘normal self’ when he last saw him only a few months before. Even his former teammate Phil Carrick, whose friendship with my dad almost went back to the time both of them were in short pants, was stupefied. ‘I just can’t take it in,’ he said. Another long-standing friend, Michael Parkinson (now Sir Parky), had latterly detected a certain ‘sadness in him’, but still couldn’t credit what had happened. His reply, when hearing about my dad’s suicide, was to dismiss the bringer of such awful news with the incredulous: ‘Don’t be daft. Not Bluey.’

Few knew my dad was sick, and fewer still knew the extent of that sickness, because he hid it far too well.

Torturing yourself with ‘what if?’ questions is pointless. No matter how long you dwell on them you only ever end up circling back to the spot where you started, absolutely no wiser. But you can’t help asking them anyway. So I wonder whether, if modern attitudes had been prevalent back then, allowing my dad to be more open about his depression – making his cry for help more public – he would still be here with us …

Possibly.