По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

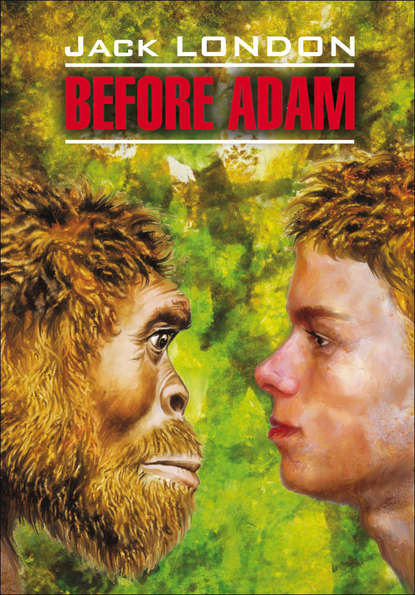

Before Adam / До Адама. Книга для чтения на английском языке

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

But they make the mistake of ignoring their own duality. They do not recognize their other-personality. They think it is their own personality, that they have only one personality; and from such a premise they can conclude only that they have lived previous lives.

But they are wrong. It is not reincarnation. I have visions of myself roaming through the forests of the Younger World; and yet it is not myself that I see but one that is only remotely a part of me, as my father and my grandfather are parts of me less remote. This other-self of mine is an ancestor, a progenitor of my progenitors in the early line of my race, himself the progeny of a line that long before his time developed fingers and toes and climbed up into the trees.

I must again, at the risk of boring, repeat that I am, in this one thing, to be considered a freak. Not alone do I possess racial memory to an enormous extent, but I possess the memories of one particular and far-removed progenitor. And yet, while this is most unusual, there is nothing over-remarkable about it.

Follow my reasoning. An instinct is a racial memory. Very good. Then you and I and all of us receive these memories from our fathers and mothers, as they received them from their fathers and mothers. Therefore there must be a medium whereby these memories are transmitted from generation to generation. This medium is what Weismann[8 - Weismann – Август Вейсман (1834–1914), немецкий биолог, теоретик эволюционного учения] terms the “germplasm.” It carries the memories of the whole evolution of the race. These memories are dim and confused, and many of them are lost. But some strains of germplasm carry an excessive freightage of memories – are, to be scientific, more atavistic than other strains; and such a strain is mine. I am a freak of heredity, an atavistic nightmare – call me what you will; but here I am, real and alive, eating three hearty meals a day, and what are you going to do about it?

And now, before I take up my tale, I want to anticipate the doubting Thomases[9 - the doubting Th omases – ср. русск. Фома неверующий] of psychology, who are prone to scoff, and who would otherwise surely say that the coherence of my dreams is due to overstudy and the subconscious projection of my knowledge of evolution into my dreams. In the first place, I have never been a zealous student. I graduated last of my class. I cared more for athletics, and – there is no reason I should not confess it – more for billiards.

Further, I had no knowledge of evolution until I was at college, whereas in my childhood and youth I had already lived in my dreams all the details of that other, long-ago life. I will say, however, that these details were mixed and incoherent until I came to know the science of evolution. Evolution was the key. It gave the explanation, gave sanity to the pranks of this atavistic brain of mine that, modern and normal, harked back to a past so remote as to be contemporaneous with the raw beginnings of mankind.

For in this past I know of, man, as we to-day know him, did not exist. It was in the period of his becoming that I must have lived and had my being.

Chapter III

The commonest dream of my early childhood was something like this: It seemed that I was very small and that I lay curled up in a sort of nest of twigs and boughs. Sometimes I was lying on my back. In this position it seemed that I spent many hours, watching the play of sunlight on the foliage and the stirring of the leaves by the wind. Often the nest itself moved back and forth when the wind was strong.

But always, while so lying in the nest, I was mastered as of tremendous space beneath me. I never saw it, I never peered over the edge of the nest to see; but I KNEW and feared that space that lurked just beneath me and that ever threatened me like a maw of some all-devouring monster.

This dream, in which I was quiescent and which was more like a condition than an experience of action, I dreamed very often in my early childhood. But suddenly, there would rush into the very midst of it strange forms and ferocious happenings, the thunder and crashing of storm, or unfamiliar landscapes such as in my wake-a-day life I had never seen. The result was confusion and nightmare. I could comprehend nothing of it. There was no logic of sequence.

You see, I did not dream consecutively. One moment I was a wee babe[10 - was a wee babe – (разг.) был младенцем] of the Younger World lying in my tree nest; the next moment I was a grown man of the Younger World locked in combat with the hideous Red-Eye; and the next moment I was creeping carefully down to the water-hole in the heat of the day. Events, years apart in their occurrence in the Younger World, occurred with me within the space of several minutes, or seconds.

It was all a jumble, but this jumble I shall not inflict upon you. It was not until I was a young man and had dreamed many thousand times, that everything straightened out and became clear and plain. Then it was that I got the clew of time, and was able to piece together events and actions in their proper order. Thus was I able to reconstruct the vanished Younger World as it was at the time I lived in it – or at the time my other-self lived in it. The distinction does not matter; for I, too, the modern man, have gone back and lived that early life in the company of my other-self.

For your convenience, since this is to be no sociological screed, I shall frame together the different events into a comprehensive story. For there is a certain thread of continuity and happening that runs through all the dreams. There is my friendship with Lop-Ear, for instance. Also, there is the enmity of Red-Eye, and the love of the Swift One. Taking it all in all, a fairly coherent and interesting story I am sure you will agree.

I do not remember much of my mother. Possibly the earliest recollection I have of her – and certainly the sharpest – is the following: It seemed I was lying on the ground. I was somewhat older than during the nest days, but still helpless. I rolled about in the dry leaves, playing with them and making crooning, rasping noises in my throat. The sun shone warmly and I was happy, and comfortable. I was in a little open space. Around me, on all sides, were bushes and fern-like growths, and overhead and all about were the trunks and branches of forest trees.

Suddenly I heard a sound. I sat upright and listened. I made no movement. The little noises died down in my throat, and I sat as one petrified. The sound drew closer. It was like the grunt of a pig. Then I began to hear the sounds caused by the moving of a body through the brush. Next I saw the ferns agitated by the passage of the body. Then the ferns parted, and I saw gleaming eyes, a long snout, and white tusks.

It was a wild boar. He peered at me curiously. He grunted once or twice and shifted his weight from one foreleg to the other, at the same time moving his head from side to side and swaying the ferns. Still I sat as one petrified, my eyes unblinking as I stared at him, fear eating at my heart.

It seemed that this movelessness and silence on my part was what was expected of me. I was not to cry out in the face of fear. It was a dictate of instinct.[11 - It was a dictate of instinct. – (разг.) Так требовал инстинкт.] And so I sat there and waited for I knew not what. The boar thrust the ferns aside and stepped into the open. The curiosity went out of his eyes, and they gleamed cruelly. He tossed his head at me threateningly and advanced a step. This he did again, and yet again.

Then I screamed… or shrieked – I cannot describe it, but it was a shrill and terrible cry. And it seems that it, too, at this stage of the proceedings, was the thing expected of me. From not far away came an answering cry. My sounds seemed momentarily to disconcert the boar, and while he halted and shifted his weight with indecision, an apparition burst upon us.

She was like a large orangutan, my mother, or like a chimpanzee, and yet, in sharp and definite ways, quite different. She was heavier of build than they, and had less hair. Her arms were not so long, and her legs were stouter. She wore no clothes – only her natural hair. And I can tell you she was a fury when she was excited.

And like a fury she dashed upon the scene. She was gritting her teeth, making frightful grimaces, snarling, uttering sharp and continuous cries that sounded like “kh-ah! kh-ah!” So sudden and formidable was her appearance that the boar involuntarily bunched himself together on the defensive and bristled as she swerved toward him. Then she swerved toward me. She had quite taken the breath out of him. I knew just what to do in that moment of time she had gained. I leaped to meet her, catching her about the waist and holding on hand and foot – yes, by my feet; I could hold on by them as readily as by my hands. I could feel in my tense grip the pull of the hair as her skin and her muscles moved beneath with her efforts.

As I say, I leaped to meet her, and on the instant she leaped straight up into the air, catching an overhanging branch with her hands. The next instant, with clashing tusks, the boar drove past underneath. He had recovered from his surprise and sprung forward, emitting a squeal that was almost a trumpeting. At any rate it was a call, for it was followed by the rushing of bodies through the ferns and brush from all directions.

From every side wild hogs dashed into the open space – a score of them. But my mother swung over the top of a thick limb, a dozen feet from the ground, and, still holding on to her, we perched there in safety. She was very excited. She chattered and screamed, and scolded down at the bristling, tooth-gnashing circle that had gathered beneath. I, too, trembling, peered down at the angry beasts and did my best to imitate my mother’s cries.

From the distance came similar cries, only pitched deeper, into a sort of roaring bass. These grew momentarily louder, and soon I saw him approaching, my father – at least, by all the evidence of the times, I am driven to conclude that he was my father.

He was not an extremely prepossessing father, as fathers go. He seemed half man, and half ape, and yet not ape, and not yet man. I fail to describe him. There is nothing like him to-day on the earth, under the earth, nor in the earth. He was a large man in his day[12 - in his day – (зд.) для своего времени], and he must have weighed all of a hundred and thirty pounds. His face was broad and flat, and the eyebrows overhung the eyes. The eyes themselves were small, deep-set, and close together. He had practically no nose at all. It was squat and broad, apparently without any bridge, while the nostrils were like two holes in the face, opening outward instead of down.

The forehead slanted back from the eyes, and the hair began right at the eyes and ran up over the head. The head itself was preposterously small and was supported on an equally preposterous, thick, short neck.

There was an elemental economy about his body – as was there about all our bodies. The chest was deep, it is true, cavernously deep; but there were no full-swelling muscles, no wide-spreading shoulders, no clean-limbed straightness, no generous symmetry of outline. It represented strength, that body of my father’s, strength without beauty; ferocious, primordial strength, made to clutch and gripe and rend and destroy.

His hips were thin; and the legs, lean and hairy, were crooked and stringy-muscled. In fact, my father’s legs were more like arms. They were twisted and gnarly, and with scarcely the semblance of the full meaty calf such as graces your leg and mine. I remember he could not walk on the flat of his foot. This was because it was a prehensile foot, more like a hand than a foot. The great toe, instead of being in line with the other toes, opposed them, like a thumb, and its opposition to the other toes was what enabled him to get a grip with his foot[13 - what enabled him to get a grip with his foot – (разг.) что позволяло ему хватать и цепляться ногами]. This was why he could not walk on the flat of his foot.

But his appearance was no more unusual than the manner of his coming, there to my mother and me as we perched above the angry wild pigs. He came through the trees, leaping from limb to limb and from tree to tree; and he came swiftly. I can see him now, in my wake-a-day life, as I write this, swinging along through the trees, a four-handed, hairy creature, howling with rage, pausing now and again to beat his chest with his clenched fist, leaping ten-and-fifteen-foot gaps, catching a branch with one hand and swinging on across another gap to catch with his other hand and go on, never hesitating, never at a loss[14 - never hesitating, never at a loss – (разг.) не колеблясь, не задумываясь] as to how to proceed on his arboreal way.

And as I watched him I felt in my own being, in my very muscles themselves, the surge and thrill of desire to go leaping from bough to bough; and I felt also the guarantee of the latent power in that being and in those muscles of mine. And why not? Little boys watch their fathers swing axes and fell trees, and feel in themselves that some day they, too, will swing axes and fell trees. And so with me. The life that was in me was constituted to do what my father did, and it whispered to me secretly and ambitiously of aerial paths and forest flights.

At last my father joined us. He was extremely angry. I remember the outthrust of his protruding underlip as he glared down at the wild pigs. He snarled something like a dog, and I remember that his eye-teeth were large, like fangs, and that they impressed me tremendously.

His conduct served only the more to infuriate the pigs. He broke off twigs and small branches and flung them down upon our enemies. He even hung by one hand, tantalizingly just beyond reach, and mocked them as they gnashed their tusks with impotent rage. Not content with this, he broke off a stout branch, and, holding on with one hand and foot, jabbed the infuriated beasts in the sides and whacked them across their noses. Needless to state, my mother and I enjoyed the sport.

But one tires of all good things, and in the end, my father, chuckling maliciously the while, led the way across the trees. Now it was that my ambitions ebbed away, and I became timid, holding tightly to my mother as she climbed and swung through space. I remember when the branch broke with her weight. She had made a wide leap, and with the snap of the wood I was overwhelmed with the sickening consciousness of falling through space, the pair of us. The forest and the sunshine on the rustling leaves vanished from my eyes. I had a fading glimpse of my father abruptly arresting his progress to look, and then all was blackness.

The next moment I was awake, in my sheeted bed, sweating, trembling, nauseated. The window was up, and a cool air was blowing through the room. The night-lamp was burning calmly. And because of this I take it that the wild pigs did not get us, that we never fetched bottom; else I should not be here now, a thousand centuries after, to remember the event.

And now put yourself in my place for a moment. Walk with me a bit in my tender childhood, bed with me a night and imagine yourself dreaming such incomprehensible horrors. Remember I was an inexperienced child. I had never seen a wild boar in my life. For that matter[15 - For that matter – (разг.) Раз уж на то пошло; если уж говорить об этом] I had never seen a domesticated pig. The nearest approach to one that I had seen was breakfast bacon sizzling in its fat. And yet here, real as life, wild boars dashed through my dreams, and I, with fantastic parents, swung through the lofty tree-spaces.

Do you wonder that I was frightened and oppressed by my nightmare-ridden nights? I was accursed. And, worst of all, I was afraid to tell. I do not know why, except that I had a feeling of guilt, though I knew no better of what I was guilty. So it was, through long years, that I suffered in silence, until I came to man’s estate and learned the why and wherefore of my dreams.

Chapter IV

There is one puzzling thing about these prehistoric memories of mine. It is the vagueness of the time element. I do not always know the order of events; – or can I tell, between some events, whether one, two, or four or five years have elapsed. I can only roughly tell the passage of time by judging the changes in the appearance and pursuits of my fellows.

Also, I can apply the logic of events to the various happenings. For instance, there is no doubt whatever that my mother and I were treed by the wild pigs and fled and fell in the days before I made the acquaintance of Lop-Ear, who became what I may call my boyhood chum. And it is just as conclusive that between these two periods I must have left my mother.

I have no memory of my father than the one I have given. Never, in the years that followed, did he reappear. And from my knowledge of the times, the only explanation possible lies in that he perished shortly after the adventure with the wild pigs. That it must have been an untimely end, there is no discussion. He was in full vigor, and only sudden and violent death could have taken him off. But I know not the manner of his going – whether he was drowned in the river, or was swallowed by a snake, or went into the stomach of old Saber-Tooth, the tiger, is beyond my knowledge.

For know that, I remember only the things I saw myself, with my own eyes, in those prehistoric days. If my mother knew my father’s end, she never told me. For that matter I doubt if she had a vocabulary adequate to convey such information. Perhaps, all told, the Folk in that day had a vocabulary of thirty or forty sounds.

I call them SOUNDS, rather than WORDS, because sounds they were primarily. They had no fixed values, to be altered by adjectives and adverbs. These latter were tools of speech not yet invented. Instead of qualifying nouns or verbs by the use of adjectives and adverbs, we qualified sounds by intonation, by changes in quantity and pitch, by retarding and by accelerating. The length of time employed in the utterance of a particular sound shaded its meaning.

We had no conjugation. One judged the tense by the context. We talked only concrete things because we thought only concrete things. Also, we depended largely on pantomime. The simplest abstraction was practically beyond our thinking; and when one did happen to think one, he was hard put to communicate it to his fellows. There were no sounds for it. He was pressing beyond the limits of his vocabulary. If he invented sounds for it, his fellows did not understand the sounds. Then it was that he fell back on pantomime, illustrating the thought wherever possible and at the same time repeating the new sound over and over again.

Thus language grew. By the few sounds we possessed we were enabled to think a short distance beyond those sounds; then came the need for new sounds wherewith to express the new thought. Sometimes, however, we thought too long a distance in advance of our sounds, managed to achieve abstractions (dim ones I grant), which we failed utterly to make known to other folk. After all, language did not grow fast in that day.

Oh, believe me, we were amazingly simple. But we did know a lot that is not known to-day. We could twitch our ears, prick them up and flatten them down at will. And we could scratch between our shoulders with ease. We could throw stones with our feet. I have done it many a time[16 - many a time – (разг.) не раз, неоднократно]. And for that matter, I could keep my knees straight, bend forward from the hips, and touch, not the tips of my fingers, but the points of my elbows, to the ground. And as for bird-nesting – well, I only wish the twentieth-century boy could see us. But we made no collections of eggs. We ate them.

I remember – but I outrun my story. First let me tell of Lop-Ear and our friendship. Very early in my life, I separated from my mother. Possibly this was because, after the death of my father, she took to herself a second husband. I have few recollections of him, and they are not of the best. He was a light fellow. There was no solidity to him. He was too voluble. His infernal chattering worries me even now as I think of it. His mind was too inconsequential to permit him to possess purpose. Monkeys in their cages always remind me of him. He was monkeyish. That is the best description I can give of him.

He hated me from the first. And I quickly learned to be afraid of him and his malicious pranks. Whenever he came in sight I crept close to my mother and clung to her. But I was growing older all the time, and it was inevitable that I should from time to time stray from her, and stray farther and farther. And these were the opportunities that the Chatterer waited for. (I may as well explain that we bore no names in those days; were not known by any name. For the sake of convenience I have myself given names to the various Folk I was more closely in contact with, and the “Chatterer” is the most fitting description I can find for that precious stepfather of mine. As for me, I have named myself “Big-Tooth.” My eye-teeth were pronouncedly large.)

But to return to the Chatterer. He persistently terrorized me. He was always pinching me and cufing me, and on occasion he was not above biting me. Often my mother interfered, and the way she made his fur fly[17 - made his fur fly – (разг.) от него пух и перья летели] was a joy to see. But the result of all this was a beautiful and unending family quarrel, in which I was the bone of contention[18 - was the bone of contention – (разг.) был яблоком раздора].

No, my home-life was not happy. I smile to myself as I write the phrase. Home-life! Home! I had no home in the modern sense of the term. My home was an association, not a habitation. I lived in my mother’s care, not in a house. And my mother lived anywhere, so long as when night came she was above the ground.

My mother was old-fashioned. She still clung to her trees. It is true, the more progressive members of our horde lived in the caves above the river. But my mother was suspicious and unprogressive. The trees were good enough for her. Of course, we had one particular tree in which we usually roosted, though we often roosted in other trees when nightfall caught us. In a convenient fork was a sort of rude platform of twigs and branches and creeping things. It was more like a huge bird-nest than anything else, though it was a thousand times cruder in the weaving than any bird-nest. But it had one feature that I have never seen attached to any bird-nest, namely, a roof.

But they are wrong. It is not reincarnation. I have visions of myself roaming through the forests of the Younger World; and yet it is not myself that I see but one that is only remotely a part of me, as my father and my grandfather are parts of me less remote. This other-self of mine is an ancestor, a progenitor of my progenitors in the early line of my race, himself the progeny of a line that long before his time developed fingers and toes and climbed up into the trees.

I must again, at the risk of boring, repeat that I am, in this one thing, to be considered a freak. Not alone do I possess racial memory to an enormous extent, but I possess the memories of one particular and far-removed progenitor. And yet, while this is most unusual, there is nothing over-remarkable about it.

Follow my reasoning. An instinct is a racial memory. Very good. Then you and I and all of us receive these memories from our fathers and mothers, as they received them from their fathers and mothers. Therefore there must be a medium whereby these memories are transmitted from generation to generation. This medium is what Weismann[8 - Weismann – Август Вейсман (1834–1914), немецкий биолог, теоретик эволюционного учения] terms the “germplasm.” It carries the memories of the whole evolution of the race. These memories are dim and confused, and many of them are lost. But some strains of germplasm carry an excessive freightage of memories – are, to be scientific, more atavistic than other strains; and such a strain is mine. I am a freak of heredity, an atavistic nightmare – call me what you will; but here I am, real and alive, eating three hearty meals a day, and what are you going to do about it?

And now, before I take up my tale, I want to anticipate the doubting Thomases[9 - the doubting Th omases – ср. русск. Фома неверующий] of psychology, who are prone to scoff, and who would otherwise surely say that the coherence of my dreams is due to overstudy and the subconscious projection of my knowledge of evolution into my dreams. In the first place, I have never been a zealous student. I graduated last of my class. I cared more for athletics, and – there is no reason I should not confess it – more for billiards.

Further, I had no knowledge of evolution until I was at college, whereas in my childhood and youth I had already lived in my dreams all the details of that other, long-ago life. I will say, however, that these details were mixed and incoherent until I came to know the science of evolution. Evolution was the key. It gave the explanation, gave sanity to the pranks of this atavistic brain of mine that, modern and normal, harked back to a past so remote as to be contemporaneous with the raw beginnings of mankind.

For in this past I know of, man, as we to-day know him, did not exist. It was in the period of his becoming that I must have lived and had my being.

Chapter III

The commonest dream of my early childhood was something like this: It seemed that I was very small and that I lay curled up in a sort of nest of twigs and boughs. Sometimes I was lying on my back. In this position it seemed that I spent many hours, watching the play of sunlight on the foliage and the stirring of the leaves by the wind. Often the nest itself moved back and forth when the wind was strong.

But always, while so lying in the nest, I was mastered as of tremendous space beneath me. I never saw it, I never peered over the edge of the nest to see; but I KNEW and feared that space that lurked just beneath me and that ever threatened me like a maw of some all-devouring monster.

This dream, in which I was quiescent and which was more like a condition than an experience of action, I dreamed very often in my early childhood. But suddenly, there would rush into the very midst of it strange forms and ferocious happenings, the thunder and crashing of storm, or unfamiliar landscapes such as in my wake-a-day life I had never seen. The result was confusion and nightmare. I could comprehend nothing of it. There was no logic of sequence.

You see, I did not dream consecutively. One moment I was a wee babe[10 - was a wee babe – (разг.) был младенцем] of the Younger World lying in my tree nest; the next moment I was a grown man of the Younger World locked in combat with the hideous Red-Eye; and the next moment I was creeping carefully down to the water-hole in the heat of the day. Events, years apart in their occurrence in the Younger World, occurred with me within the space of several minutes, or seconds.

It was all a jumble, but this jumble I shall not inflict upon you. It was not until I was a young man and had dreamed many thousand times, that everything straightened out and became clear and plain. Then it was that I got the clew of time, and was able to piece together events and actions in their proper order. Thus was I able to reconstruct the vanished Younger World as it was at the time I lived in it – or at the time my other-self lived in it. The distinction does not matter; for I, too, the modern man, have gone back and lived that early life in the company of my other-self.

For your convenience, since this is to be no sociological screed, I shall frame together the different events into a comprehensive story. For there is a certain thread of continuity and happening that runs through all the dreams. There is my friendship with Lop-Ear, for instance. Also, there is the enmity of Red-Eye, and the love of the Swift One. Taking it all in all, a fairly coherent and interesting story I am sure you will agree.

I do not remember much of my mother. Possibly the earliest recollection I have of her – and certainly the sharpest – is the following: It seemed I was lying on the ground. I was somewhat older than during the nest days, but still helpless. I rolled about in the dry leaves, playing with them and making crooning, rasping noises in my throat. The sun shone warmly and I was happy, and comfortable. I was in a little open space. Around me, on all sides, were bushes and fern-like growths, and overhead and all about were the trunks and branches of forest trees.

Suddenly I heard a sound. I sat upright and listened. I made no movement. The little noises died down in my throat, and I sat as one petrified. The sound drew closer. It was like the grunt of a pig. Then I began to hear the sounds caused by the moving of a body through the brush. Next I saw the ferns agitated by the passage of the body. Then the ferns parted, and I saw gleaming eyes, a long snout, and white tusks.

It was a wild boar. He peered at me curiously. He grunted once or twice and shifted his weight from one foreleg to the other, at the same time moving his head from side to side and swaying the ferns. Still I sat as one petrified, my eyes unblinking as I stared at him, fear eating at my heart.

It seemed that this movelessness and silence on my part was what was expected of me. I was not to cry out in the face of fear. It was a dictate of instinct.[11 - It was a dictate of instinct. – (разг.) Так требовал инстинкт.] And so I sat there and waited for I knew not what. The boar thrust the ferns aside and stepped into the open. The curiosity went out of his eyes, and they gleamed cruelly. He tossed his head at me threateningly and advanced a step. This he did again, and yet again.

Then I screamed… or shrieked – I cannot describe it, but it was a shrill and terrible cry. And it seems that it, too, at this stage of the proceedings, was the thing expected of me. From not far away came an answering cry. My sounds seemed momentarily to disconcert the boar, and while he halted and shifted his weight with indecision, an apparition burst upon us.

She was like a large orangutan, my mother, or like a chimpanzee, and yet, in sharp and definite ways, quite different. She was heavier of build than they, and had less hair. Her arms were not so long, and her legs were stouter. She wore no clothes – only her natural hair. And I can tell you she was a fury when she was excited.

And like a fury she dashed upon the scene. She was gritting her teeth, making frightful grimaces, snarling, uttering sharp and continuous cries that sounded like “kh-ah! kh-ah!” So sudden and formidable was her appearance that the boar involuntarily bunched himself together on the defensive and bristled as she swerved toward him. Then she swerved toward me. She had quite taken the breath out of him. I knew just what to do in that moment of time she had gained. I leaped to meet her, catching her about the waist and holding on hand and foot – yes, by my feet; I could hold on by them as readily as by my hands. I could feel in my tense grip the pull of the hair as her skin and her muscles moved beneath with her efforts.

As I say, I leaped to meet her, and on the instant she leaped straight up into the air, catching an overhanging branch with her hands. The next instant, with clashing tusks, the boar drove past underneath. He had recovered from his surprise and sprung forward, emitting a squeal that was almost a trumpeting. At any rate it was a call, for it was followed by the rushing of bodies through the ferns and brush from all directions.

From every side wild hogs dashed into the open space – a score of them. But my mother swung over the top of a thick limb, a dozen feet from the ground, and, still holding on to her, we perched there in safety. She was very excited. She chattered and screamed, and scolded down at the bristling, tooth-gnashing circle that had gathered beneath. I, too, trembling, peered down at the angry beasts and did my best to imitate my mother’s cries.

From the distance came similar cries, only pitched deeper, into a sort of roaring bass. These grew momentarily louder, and soon I saw him approaching, my father – at least, by all the evidence of the times, I am driven to conclude that he was my father.

He was not an extremely prepossessing father, as fathers go. He seemed half man, and half ape, and yet not ape, and not yet man. I fail to describe him. There is nothing like him to-day on the earth, under the earth, nor in the earth. He was a large man in his day[12 - in his day – (зд.) для своего времени], and he must have weighed all of a hundred and thirty pounds. His face was broad and flat, and the eyebrows overhung the eyes. The eyes themselves were small, deep-set, and close together. He had practically no nose at all. It was squat and broad, apparently without any bridge, while the nostrils were like two holes in the face, opening outward instead of down.

The forehead slanted back from the eyes, and the hair began right at the eyes and ran up over the head. The head itself was preposterously small and was supported on an equally preposterous, thick, short neck.

There was an elemental economy about his body – as was there about all our bodies. The chest was deep, it is true, cavernously deep; but there were no full-swelling muscles, no wide-spreading shoulders, no clean-limbed straightness, no generous symmetry of outline. It represented strength, that body of my father’s, strength without beauty; ferocious, primordial strength, made to clutch and gripe and rend and destroy.

His hips were thin; and the legs, lean and hairy, were crooked and stringy-muscled. In fact, my father’s legs were more like arms. They were twisted and gnarly, and with scarcely the semblance of the full meaty calf such as graces your leg and mine. I remember he could not walk on the flat of his foot. This was because it was a prehensile foot, more like a hand than a foot. The great toe, instead of being in line with the other toes, opposed them, like a thumb, and its opposition to the other toes was what enabled him to get a grip with his foot[13 - what enabled him to get a grip with his foot – (разг.) что позволяло ему хватать и цепляться ногами]. This was why he could not walk on the flat of his foot.

But his appearance was no more unusual than the manner of his coming, there to my mother and me as we perched above the angry wild pigs. He came through the trees, leaping from limb to limb and from tree to tree; and he came swiftly. I can see him now, in my wake-a-day life, as I write this, swinging along through the trees, a four-handed, hairy creature, howling with rage, pausing now and again to beat his chest with his clenched fist, leaping ten-and-fifteen-foot gaps, catching a branch with one hand and swinging on across another gap to catch with his other hand and go on, never hesitating, never at a loss[14 - never hesitating, never at a loss – (разг.) не колеблясь, не задумываясь] as to how to proceed on his arboreal way.

And as I watched him I felt in my own being, in my very muscles themselves, the surge and thrill of desire to go leaping from bough to bough; and I felt also the guarantee of the latent power in that being and in those muscles of mine. And why not? Little boys watch their fathers swing axes and fell trees, and feel in themselves that some day they, too, will swing axes and fell trees. And so with me. The life that was in me was constituted to do what my father did, and it whispered to me secretly and ambitiously of aerial paths and forest flights.

At last my father joined us. He was extremely angry. I remember the outthrust of his protruding underlip as he glared down at the wild pigs. He snarled something like a dog, and I remember that his eye-teeth were large, like fangs, and that they impressed me tremendously.

His conduct served only the more to infuriate the pigs. He broke off twigs and small branches and flung them down upon our enemies. He even hung by one hand, tantalizingly just beyond reach, and mocked them as they gnashed their tusks with impotent rage. Not content with this, he broke off a stout branch, and, holding on with one hand and foot, jabbed the infuriated beasts in the sides and whacked them across their noses. Needless to state, my mother and I enjoyed the sport.

But one tires of all good things, and in the end, my father, chuckling maliciously the while, led the way across the trees. Now it was that my ambitions ebbed away, and I became timid, holding tightly to my mother as she climbed and swung through space. I remember when the branch broke with her weight. She had made a wide leap, and with the snap of the wood I was overwhelmed with the sickening consciousness of falling through space, the pair of us. The forest and the sunshine on the rustling leaves vanished from my eyes. I had a fading glimpse of my father abruptly arresting his progress to look, and then all was blackness.

The next moment I was awake, in my sheeted bed, sweating, trembling, nauseated. The window was up, and a cool air was blowing through the room. The night-lamp was burning calmly. And because of this I take it that the wild pigs did not get us, that we never fetched bottom; else I should not be here now, a thousand centuries after, to remember the event.

And now put yourself in my place for a moment. Walk with me a bit in my tender childhood, bed with me a night and imagine yourself dreaming such incomprehensible horrors. Remember I was an inexperienced child. I had never seen a wild boar in my life. For that matter[15 - For that matter – (разг.) Раз уж на то пошло; если уж говорить об этом] I had never seen a domesticated pig. The nearest approach to one that I had seen was breakfast bacon sizzling in its fat. And yet here, real as life, wild boars dashed through my dreams, and I, with fantastic parents, swung through the lofty tree-spaces.

Do you wonder that I was frightened and oppressed by my nightmare-ridden nights? I was accursed. And, worst of all, I was afraid to tell. I do not know why, except that I had a feeling of guilt, though I knew no better of what I was guilty. So it was, through long years, that I suffered in silence, until I came to man’s estate and learned the why and wherefore of my dreams.

Chapter IV

There is one puzzling thing about these prehistoric memories of mine. It is the vagueness of the time element. I do not always know the order of events; – or can I tell, between some events, whether one, two, or four or five years have elapsed. I can only roughly tell the passage of time by judging the changes in the appearance and pursuits of my fellows.

Also, I can apply the logic of events to the various happenings. For instance, there is no doubt whatever that my mother and I were treed by the wild pigs and fled and fell in the days before I made the acquaintance of Lop-Ear, who became what I may call my boyhood chum. And it is just as conclusive that between these two periods I must have left my mother.

I have no memory of my father than the one I have given. Never, in the years that followed, did he reappear. And from my knowledge of the times, the only explanation possible lies in that he perished shortly after the adventure with the wild pigs. That it must have been an untimely end, there is no discussion. He was in full vigor, and only sudden and violent death could have taken him off. But I know not the manner of his going – whether he was drowned in the river, or was swallowed by a snake, or went into the stomach of old Saber-Tooth, the tiger, is beyond my knowledge.

For know that, I remember only the things I saw myself, with my own eyes, in those prehistoric days. If my mother knew my father’s end, she never told me. For that matter I doubt if she had a vocabulary adequate to convey such information. Perhaps, all told, the Folk in that day had a vocabulary of thirty or forty sounds.

I call them SOUNDS, rather than WORDS, because sounds they were primarily. They had no fixed values, to be altered by adjectives and adverbs. These latter were tools of speech not yet invented. Instead of qualifying nouns or verbs by the use of adjectives and adverbs, we qualified sounds by intonation, by changes in quantity and pitch, by retarding and by accelerating. The length of time employed in the utterance of a particular sound shaded its meaning.

We had no conjugation. One judged the tense by the context. We talked only concrete things because we thought only concrete things. Also, we depended largely on pantomime. The simplest abstraction was practically beyond our thinking; and when one did happen to think one, he was hard put to communicate it to his fellows. There were no sounds for it. He was pressing beyond the limits of his vocabulary. If he invented sounds for it, his fellows did not understand the sounds. Then it was that he fell back on pantomime, illustrating the thought wherever possible and at the same time repeating the new sound over and over again.

Thus language grew. By the few sounds we possessed we were enabled to think a short distance beyond those sounds; then came the need for new sounds wherewith to express the new thought. Sometimes, however, we thought too long a distance in advance of our sounds, managed to achieve abstractions (dim ones I grant), which we failed utterly to make known to other folk. After all, language did not grow fast in that day.

Oh, believe me, we were amazingly simple. But we did know a lot that is not known to-day. We could twitch our ears, prick them up and flatten them down at will. And we could scratch between our shoulders with ease. We could throw stones with our feet. I have done it many a time[16 - many a time – (разг.) не раз, неоднократно]. And for that matter, I could keep my knees straight, bend forward from the hips, and touch, not the tips of my fingers, but the points of my elbows, to the ground. And as for bird-nesting – well, I only wish the twentieth-century boy could see us. But we made no collections of eggs. We ate them.

I remember – but I outrun my story. First let me tell of Lop-Ear and our friendship. Very early in my life, I separated from my mother. Possibly this was because, after the death of my father, she took to herself a second husband. I have few recollections of him, and they are not of the best. He was a light fellow. There was no solidity to him. He was too voluble. His infernal chattering worries me even now as I think of it. His mind was too inconsequential to permit him to possess purpose. Monkeys in their cages always remind me of him. He was monkeyish. That is the best description I can give of him.

He hated me from the first. And I quickly learned to be afraid of him and his malicious pranks. Whenever he came in sight I crept close to my mother and clung to her. But I was growing older all the time, and it was inevitable that I should from time to time stray from her, and stray farther and farther. And these were the opportunities that the Chatterer waited for. (I may as well explain that we bore no names in those days; were not known by any name. For the sake of convenience I have myself given names to the various Folk I was more closely in contact with, and the “Chatterer” is the most fitting description I can find for that precious stepfather of mine. As for me, I have named myself “Big-Tooth.” My eye-teeth were pronouncedly large.)

But to return to the Chatterer. He persistently terrorized me. He was always pinching me and cufing me, and on occasion he was not above biting me. Often my mother interfered, and the way she made his fur fly[17 - made his fur fly – (разг.) от него пух и перья летели] was a joy to see. But the result of all this was a beautiful and unending family quarrel, in which I was the bone of contention[18 - was the bone of contention – (разг.) был яблоком раздора].

No, my home-life was not happy. I smile to myself as I write the phrase. Home-life! Home! I had no home in the modern sense of the term. My home was an association, not a habitation. I lived in my mother’s care, not in a house. And my mother lived anywhere, so long as when night came she was above the ground.

My mother was old-fashioned. She still clung to her trees. It is true, the more progressive members of our horde lived in the caves above the river. But my mother was suspicious and unprogressive. The trees were good enough for her. Of course, we had one particular tree in which we usually roosted, though we often roosted in other trees when nightfall caught us. In a convenient fork was a sort of rude platform of twigs and branches and creeping things. It was more like a huge bird-nest than anything else, though it was a thousand times cruder in the weaving than any bird-nest. But it had one feature that I have never seen attached to any bird-nest, namely, a roof.