По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

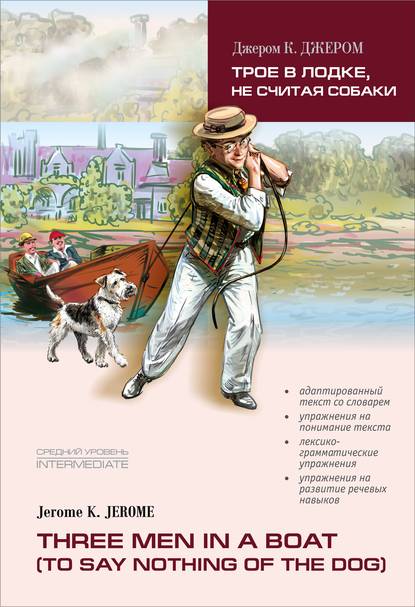

Three men in a boat / Трое в лодке, не считая собаки. Книга для чтения на английском языке

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“Um,” I replied, “lucky for you that I do. If I hadn’t woken you, you’d have lain there for the whole fortnight.”

We were growling at one another for the next few minutes, when we were interrupted by a snore from George. It reminded us of his existence. There he lay – the man who had wanted to know what time he should wake us – on his back, with his mouth wide open, and his knees stuck up.

I don’t know why it should be, but the sight of another man asleep in bed when I am up, makes me mad. It seems to me so shocking to see the precious hours of a man’s life – the priceless moments that will never come back to him again – being wasted in mere brutish sleep. There was George, throwing away the inestimable gift of time. He might have been up stuffing himself with eggs and bacon or irritating the dog instead of sprawling there.

It was a terrible thought. Harris and I seemed to be struck by it at the same instant. We determined to save him, and our own dispute was forgotten. We rushed to him and pull his blanket off him, and Harris hit him with a slipper, and I shouted in his ear, and he awoke.

“Wasermarrer?[55 - Wasermarrer? = What’s the matter? – В чем дело?]” he observed, sitting up.

“Get up, you fat-headed chunk![56 - Get up, you fat-headed chunk! – Вставай, безмозглый чурбан!]” roared Harris. “It’s quarter to ten.”

“What!” he exclaimed, jumping out of bed into the bath; “Who put this thing here?”

We told him he must have been a fool not to see the bath. We finished dressing, and, when it came to the other procedures, we remembered that we had packed the tooth-brushes and the brush and comb (that toothbrush of mine will be the death of me[57 - that tooth-brush of mine will be the death of me – эта моя зубная щетка когда-нибудь сведет меня в могилу], I know), and we had to go downstairs, and fish them out of the bag. And when we had done that George wanted the shaving tackle. We told him that he would have to go without shaving that morning, as we weren’t going to unpack that bag again for him, nor for anyone like him.

We went downstairs to have breakfast. Montmorency had invited two other dogs to come and see him, and they were whiling away the time[58 - to while away the time – коротать время] by fighting on the doorstep. We calmed them with an umbrella, and sat down to chops and cold beef.

Harris said:

“The great thing is to make a good breakfast,” and he started with a couple of chops, saying that he would take these while they were hot, as the beef could wait.

George got hold of the newspaper, and read us out the boating fatalities, and the weather forecast, which predicted “rain, cold, wet to fine[59 - wet to fine – переменная облачность]” (the worst thing that may be in weather), “occasional local thunderstorms, east wind.”

I do think that, of all the silly, irritating nonsense by which we are ill, this “weather-forecast” fraud is about the most annoying. It “forecasts” precisely what happened yesterday or the day before, and precisely the opposite of what is going to happen today.

I remember a holiday of mine being completely ruined one late autumn by our paying attention to the weather report of the local newspaper. “Heavy showers[60 - heavy showers – cильные ливни], with thunderstorms, may be expected today,” it said on Monday, and so we gave up our picnic, and stayed indoors all day, waiting for the rain. And people would pass the house, going off in cabs and coaches as jolly and merry as could be, the sun shining out, and not a cloud to be seen.

“Ah!” we said, as we stood looking out at them through the window, “won’t they come home soaked!”

And we chuckled to think how wet they were going to get, and came back and made a fire, and got our books, and arranged our collection of seaweed and shells. By twelve o’clock, with the sun pouring into the room, the heat became quite oppressive, and we wondered when those heavy showers and occasional thunderstorms were going to begin.

“Ah! They’ll come in the afternoon, you’ll find,” we said to each other. “Oh, won’t those people get wet. What a lark![61 - What a lark! – Как забавно!]”

At one o’clock, the landlady came in to ask if we weren’t going out, as it seemed such a lovely day.

“No, no,” we replied, with a knowing chuckle, “not we. We don’t mean to get wet – no, no.”

And when the afternoon was nearly gone, and still there was no sign of rain, we tried to cheer ourselves up with the idea that it would come down all at once, just as the people had started for home, and were out of the reach of any shelter[62 - out of the reach of any shelter – вдали от всякого убежища], and that they would thus get more soaked than ever. But not a drop ever fell, and it finished a grand day, and a lovely night after it.

The next morning we read that it was going to be a “warm, fine day; much heat;” and we put light clothing on, and went out, and, half-an-hour after we had started, it began raining hard, and an extremely cold wind sprang up, and both would keep on steadily for the whole day, and we came home with colds and rheumatism all over us, and went to bed.

The weather is a thing that is beyond me[63 - to be beyond smb – быть выше чьего-либо понимания] altogether. I never can understand it. The barometer is useless: it is as misleading as the newspaper forecast.

There was one barometer hanging up in a hotel at Oxford at which I was staying last spring, and, when I got there, it was pointing to “set fair[64 - set fair – ясно].” It was simply pouring with rain outside, and had been all day; and I couldn’t quite make matters out[65 - I couldn’t quite make matters out – я не мог понять, в чем дело]. I tapped the barometer, and it jumped up and pointed to “very dry.” I tapped it again the next morning, and it went up still higher, and the rain came down faster than ever. On Wednesday I went and hit it again, and the pointer went round towards “set fair,” “very dry,” and “much heat,” until it was stopped by the peg, and couldn’t go any further. It tried its best, it evidently wanted to go on, and prognosticate drought, and water famine, and sunstroke, and such things, but the peg prevented it, and it had to be content with pointing to the commonplace “very dry.”

Meanwhile, the rain came down in a steady torrent, and the lower part of the town was under water, because the river had overflowed. The fine weather never came that summer. I expect that machine must have been referring to the following spring.

Then there are those new styles of barometers, the long straight ones. I never can make head or tail of those[66 - to make head(s) or tail(s) of smb / smth – понять кого-то / что-то]. There is one side for 10 a.m. yesterday and one side for 10 a.m. today; but you can’t always get there as early as ten, you know. It rises or falls for rain and fine, with much or less wind, and if you tap it, it doesn’t tell you anything. And you’ve to correct it to sea-level, and reduce it to Fahrenheit, and even then I don’t know the answer.

But who wants to be foretold the weather? When it becomes bad enough, we don’t want to have the misery of knowing about it beforehand. The prophet we like is the old man who, on the particularly gloomy-looking morning of some day when we particularly want it to be fine, looks round the horizon with a particularly knowing eye, and says:

“Oh no, sir, I think it will clear up all right. It will break[67 - it will break – прояснится] all right enough, sir.”

“Ah, he knows”, we say, as we wish him good morning, and start off; “wonderful how these old fellows can tell!”

And we feel affection for that man which is not at all lessened by the circumstances of its not clearing up, but continuing to rain steadily all day.

“Ah, well,” we feel, “he did his best.”

Of the man that prophesies us bad weather, on the contrary, we have only bitter and revengeful thoughts.

“Going to clear up, do you think?” we shout, joyfully, as we pass.

“Well, no, sir; I’m afraid it’s settled down[68 - it’s settled down – установилось] for the day,” he replies, shaking his head.

“Stupid old fool!” we mutter, “what’s he know about it?” And, if his words prove correct, we come back feeling still more angry with him, and with a vague feeling that, somehow or other, he has had something to do with[69 - to have something to do with – иметь какое-то отношение (к делу)] it.

It was too bright and sunny on this especial morning for George’s gloomy readings about bad weather to upset us very much: and so, finding that he could not disappoint us, and was only wasting his time, he stole the cigarette that I had carefully rolled up for myself, and went.

Then Harris and I, having finished up the few things left on the table, carried out our luggage on to the doorstep, and waited for a cab.

There seemed a good deal of luggage, when we put it all together. There was the Gladstone[70 - Gladstone – сумка Глэдстоун (вместительная дорожная сумка из коричневой кожи, появившаяся в Англии в конце XIX в., часто упоминается в произведениях британских классиков)] and the small hand-bag, and the two hampers, and a large roll of rugs, and some four or five overcoats and mackintoshes, and a few umbrellas, and then there was a melon by itself in a bag, because it was too bulky to go in anywhere, and a couple of pounds of grapes in another bag, and a Japanese paper umbrella, and a frying pan, which, being too long to pack, we had wrapped round with brown paper.

It did look a lot, and Harris and I began to feel rather ashamed of it, though why we should be, I can’t see. No cab came by, but the street boys did, and got interested in the show, apparently, and stopped.

Biggs’s boy was the first to come round. Biggs is our greengrocer, and his chief talent is to obtain the services of the most abandoned and unprincipled errand-boys[71 - errand-boy – посыльный, курьер, мальчик на побегушках] that civilisation has ever produced. If anything more than usually wicked in the boy line happens in our neighbourhood, we know that it is Biggs’s latest boy. I was told that, at the time of the Great Coram Street murder[72 - Great Coram Street murder – 24 декабря 1872 г. на лондонской Грейт-Корам-cтрит в своей комнате была найдена девушка с перерезанным горлом, ее убийца так и не был найден. Есть предположения, что к этому убийству причастен Джек-потрошитель, потрясший Лондон серией подобных по почерку убийств в 1888 г., личность которого также остается неизвестной.], it was quickly concluded by our street that Biggs’s boy (for that period) was at the bottom of it[73 - to be at the bottom of smth – быть настоящей причиной чего-либо]. In reply to the severe cross-examination to which he was subjected, when he came for orders the morning after the crime, he managed to prove a complete alibi. Otherwise it would have gone hard with him. I didn’t know Biggs’s boy at that time, but, from what I have seen of them since, I should not have attached much importance to that alibi[74 - to attach importance to smth – придавать значение чему-либо] myself.

Biggs’s boy, as I have said, came round the corner. He was evidently in a great hurry, but, on catching sight of Harris and me, and Montmorency, and the things, he stopped up and stared. Harris and I frowned at him. This might have wounded a more sensitive nature, but Biggs’s boys are not, as a rule, touchy. He came to a dead stop, a yard from our step, and, leaning up against the railings, and fixed his eyes on us, he evidently meant to see this thing out[75 - he evidently meant to see this thing out – он, очевидно, намеревался досмотреть все до конца].

In another moment, the grocer’s boy passed on the opposite side of the street. Biggs’s boy cried to him:

“Hi! They are moving.”

The grocer’s boy came across, and took up a position on the other side of the step. Then the young gentleman from the boot-shop stopped, and joined Biggs’s boy.

“They are not going to starve, are they?” said the gentleman from the boot-shop.

By this time, quite a small crowd had collected, and people were asking each other what was the matter. One party (the young and silly portion of the crowd) held that it was a wedding, and pointed out Harris as the bridegroom; while the elder and more thoughtful inclined to the idea that it was a funeral, and that I was probably the corpse’s brother.

At last, an empty cab turned up (it is a street where, as a rule, and when they are not wanted, empty cabs pass at the rate of three a minute, and hang about, and get in your way), and packing ourselves and our belongings into it, and keeping out a couple of Montmorency’s friends, who had evidently sworn never to leave him, we drove away surrounded by the cheering crowd. Biggs’s boy threw a carrot after us for luck.

We got to Waterloo at eleven, and asked where the eleven-five train started from. Of course nobody knew; nobody at Waterloo ever knows where a train is going to start from, or where a train is going to, or anything about it. The porter who took our things thought it would go from number two platform, while another porter, with whom he discussed the question, had heard a rumour that it would go from number one. The station-master, on the other hand[76 - on the other hand – с другой стороны], was convinced it would start from the local platform.

To put an end to the matter[77 - to put an end to smth – положить конец чему-либо], we went upstairs, and asked the traffic superintendent, and he told us that he had just met a man, who said he had seen it at number three platform. We went to number three platform, but the authorities there said that they thought that train was the Southampton express, or else the Windsor loop. But they were sure it wasn’t the Kingston train, though why they were sure they couldn’t say.

Then our porter said he thought that it must be on the high-level platform; said he thought he knew the train. So we went to the high-level platform, and saw the engine-driver[78 - engine-driver – машинист], and asked him if he was going to Kingston. He said he couldn’t say for certain of course, but that he rather thought he was. Anyhow, if he wasn’t the 11.05 for Kingston, he said he was pretty confident he was the 9.32 for Virginia Water, or the 10 a.m. express for the Isle of Wight, or somewhere in that direction, and we should all know when we got there. We slipped half-a-crown into his hand, and begged him to be the 11.05 for Kingston.

“Nobody will ever know, on this line,” we said, “what you are, or where you’re going. You know the way, you slip off[79 - to slip off – ускользнуть] quietly and go to Kingston.”