По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

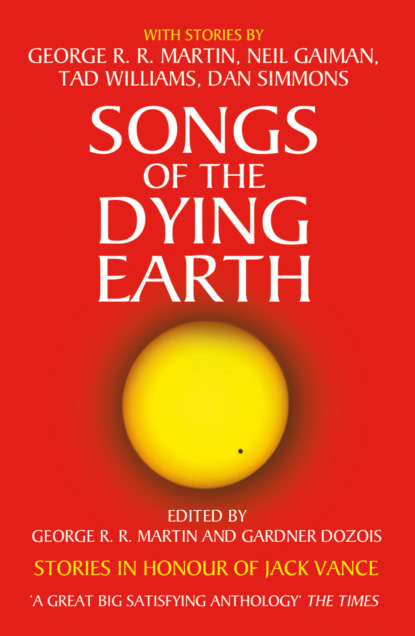

Songs of the Dying Earth

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“Now,” the owl-killer said, fixing Caulk with a beady glare. “About redress.”

Caulk, disconcerted by this buffoon’s evident abilities, found himself able to speak. “An accident!”

“Nevertheless.”

“I intended no harm! The thing attacked me!”

“Doubtless you startled it.”

“I was asleep!”

“The authorities in Azenomei take a dim view of folk who trample and stamp over the purlieus of others,” the owl-killer mused. “I know of one such who, only last week, was hoisted onto a gibbet of pettish-wood and lambasted by the populace, before being transported to the midst of the Old Forest and obliged to find his own way home. He has not yet succeeded in this endeavor, that I am aware of.”

“But—”

“It is doubly unfortunate that my brother, Pardua Mott, happens to be the head of the Azenomei Board of Fair Trading. A man of the most upright and correct rectitude, a respectability so pronounced that he had his own daughter exhibited in the Hall of Reproachable Conduct minus her undergarments, after her branding.”

“I—”

“I am, however, a fair man,” the owl-killer Mott went on judiciously. “I am prepared to concede a measure of inadvertency in your actions.”

“That’s very—”

“Rather than have you hauled in irons before my relative, which admits little other than a mild form of personal satisfaction, I shall demand an alternative form of reparation. You see,” the owl-killer said, beadily, “I need a particular owl…”

AS HE passed the distant humps of the erg-barrows along the upper shore of the estuary, Caulk relived this unfortunate course of events and grew exceedingly sour. White Alster was known to be a dismal place, with little to recommend it, unless one happened to be a connoisseur of remote rocky spars, ruined fortresses, and black sucking bogs. Moreover, Mott had been unreassuringly vague as to the whereabouts of his quarry.

“Besides,” Caulk had protested, still beneath the unnerving dictates of the pervulsion, “I am a witch-chaser, not an owl-finder. Surely that’s your remit.”

The owl-killer gave an avian blink. “Indeed, and I am, of course, aware of your profession. Your high boots, the enfoldments of your hat, the multiple hems of your coat, all speak of your calling. However, lamentable circumstances entail that should I set foot on the shores of White Alster, I will activate a locater spell and a vast shrieking will alert the hags to my presence. Besides, all that you are likely to encounter is largely within your own area of expertise. Sea-hags and tarn-wights are witches, after all, not to mention shape shifters.”

Bitterly, Caulk conceded this to be true.

“I shall give you an aid—a strand of owl-witch hair. Watch it closely. It will twitch you in the required direction.”

Steal a witch’s hair and you stole a piece of her power. Even novices knew that. Caulk looked narrowly at the strand and asked, “And if I refuse?”

He did not care to recall what came next: the indignities of a further pervulsion and the contortions it entailed. Mott’s merry laughter still stung his ears. Now here he was, sailing towards White Alster on a following wind and leaving Almery and its manses far behind. Caulk was aware of a pang, from more than the spell, that prodded him onward.

He sailed for several days, becoming increasingly bored by the dull expanse of choppy sea. Occasionally, bloat-fish rose up from the depths and regarded him with bland white eyes, whereupon Caulk was forced to summon a frothing conjuration and drive them off. Once, a great flapping bird moved ponderously from horizon to horizon, but otherwise there was little sign of life. It was with a relief mingled with apprehension that Caulk saw a broken shore rise up in the far reaches of the sea: White Alster.

It was not immediately obvious how to approach a suitable landing site, if any existed. What initially appeared to be a range of shattered turrets resolved itself into mere rock; a squat cylinder of stone that had seemed only an outcrop bore windows on its far side, but there was no sign of jetty or pier, and when Caulk looked back, the windows themselves were gone.

A bleak place, overlain with a sanguine glow in the last light of the dying sun. Caulk had seen worse, but also better. He thought with a shudder of the Land of Falling Wall, its ergs and leucomances. But White Alster, too, was said to have forests: who knew what lay within? Tempting to simply turn back towards Almery—but the pervulsion snagged at his neuronal pathways and Caulk grimaced.

At last, when he was beginning to fear that he would be obliged to sail fruitlessly along the coast forever, a flat plateau of rock became apparent, slimed with black weed and underlying a stump of castle. With renewed enthusiasm, Caulk drove the boat forward, sending out a spine of rope which clung relentlessly to the weed-decked stone. By degrees, Caulk hauled the boat inward until it was possible to make it secure by means of an ancient bronze ring and for him to step out onto the rock.

Once upon the shore of White Alster, Caulk became aware of a plangent sensation, comprised of subtle melancholy and longing. At once, the lowering sky above him, with its shades of grey and rose, and the foam lashed coast, appeared less forbidding, more appealing. He turned his face to the castle, to find that a face was watching him in return.

Caulk took an involuntary step back and narrowly missed tumbling off the dock. The face—little more than a pallid oval with black slits of eyes—had withdrawn into the shadows of the castle. A sea-hag? Caulk was too far away to tell. A bell-like note filled the air, and Caulk stumbled forward.

No. He must leave, at once. Memories of a wight burrow in Falling Water beset him, he had met this kind of thing before. Caulk muttered a spell and all was as before: the cold coast, the churning sea. Then the spell drained away like bathwater and Caulk was once more pulled forward.

As he reached the edge of the dock furthest from the sea, he realized that an eroded stair led upwards. The bell sounded again, sweet and plaintive amid the crash and spray of the waves. Caulk blinked, trying to remember why he’d come. Something about owls…But the bell once more rang out and Caulk staggered up the stair, protest ringing inside his head.

It was close to dark. A mauve twilight hung over the coast and the world was suddenly calm and hushed, the boom of the sea muted by the thick rock walls between which he now stood. The bell came again and it wasn’t a bell, not quite, but contained faint notes amongst the main strike, a fading, ancient tune. Caulk smiled, now striding eagerly upward.

She sat in the middle of her chamber, wearing violet and grey. Black hair fell down her back, bound with silver. The white face was the same, and the long dark gaze. She sat before a complex thing, an ebony instrument that almost hid her from his view, comprised of many dangling pegs and latches which she struck with a small hammer.

Caulk hesitated at last, but it was too late. The song had already reached out and snared him in silver webs of sound. He snatched at a dagger but his hand fell uselessly to his side. The sea-hag began to whistle, louder and louder, until the noise wove itself into the echoes of the instrument and Caulk dropped to the floor.

The sea-hag rose and poked him with a long toe.

“Well, well, well,” she said. “A witch-chaser, eh? From Almery, by the fashion of your hat.” She licked white lips. “I think a tea party is called for.”

CAULK LAY enveloped in coils of writhing noise. It made it difficult to think. He was still cursing himself at having fallen for the sea-hag’s lure.

The sea-hag herself stood a little distance away, in the company of her sisters. There were three of them, all cast from a similar mold, though one had hair the colour of willow leaves, and the eyes of another were a whiteless jade. They murmured and smiled and whispered behind their long hands whenever they looked in Caulk’s direction. But mostly they were occupied with admiring his daggers.

The tea set sat on a nearby table, next to the curious instrument. Caulk could see lamplight through the thin china cups, which were embellished with roses. He strained at the bonds of sound, but they were as tight as ropes and his struggles only constrained him further. The sea-hags gave little glinting laughs.

“Not long now,” one of them said. She bent and drew a fingernail down Caulk’s cheek. He felt a trickle of wetness in its wake, followed by the familiar tang of iron.

“We want you to choose,” another sea-hag said. “Which one of us is the fairest? Whoever you choose shall take the longest knife.”

Death, to touch the daggers of a witch-chaser. They’d have to be cleansed, if he got out of here. Caulk took a long breath, storing it up.

“Shall we?” the willow-haired hag simpered. The sisters sat down at the table, arranging their tattered garments with fastidious care. The blackhaired hag poured tea, which descended in a steaming dark stream into the cups. It did not look like tea, thought Caulk, squinting up from the floor. It didn’t smell like it, either. He took another breath, judging the moment. The sound writhed around him, holding him fast.

“So,” the black-haired hag said, taking a bite of a small mossy cake. “Which one of us, then?”

Caulk clamped his mouth shut and glared at her.

“Oh,” green-hair whispered, “he doesn’t want to play!”

“We’ll make him play!” Black-hair rose, taking one of Caulk’s daggers, thin as a pin, from its holster. Caulk sucked in another breath.

“Speak!”

Caulk did not speak. He thought he had it now. He pursed his lips and whistled, emitting a high-pitched stream of sound. He heard it mesh with the bonds that held him, throwing them outward. The sea-hags screamed, clapping their hands to their ears. Caulk took a frantic breath and whistled louder, feeling his face grow redder with the effort, but the bonds held, and held…He felt the break a second before it happened, sensing the shift in tone which signified that the sound-web was about to snap. Then it shattered. In an instant Caulk was on his feet, snatching at the dagger as thin as a pin with his left hand, and a dagger as white as bone with his right. Two sea-hags went down in a rush of greenish blood over the tea cups, struck through the throat. That left the willow-haired woman, whom Caulk killed with the black dagger, up under the ribs. She cursed him as she died, but Caulk laughed and whistled it away.

Gasping, he lent on the wall to get his breath back. The stone felt rough and wet beneath his hand. At the end of the chamber, a little arched window looked out onto darkness. Caulk peered through it and saw the glint of the heaving sea far below. Salt water is always a power: Caulk, with a remaining scrap of a spell, called up an arch of foam and cleansed the daggers. The bodies of the sea-hags were already rotting down into kelp and slime.

His head clearing somewhat, he remembered the instructions given to him by the owl-killer.

They frequent a tarn called Llantow, to the north, between two hills, not far from the coast. I cannot provide you with a map. You will have to watch the hair.

Not very helpful, Caulk had thought at the time, with the pervulsion twinging inside his head. He thought the same now, but perhaps the seahag’s fortress contained a map? Gently, he tried the door and it swung open. Caulk stepped out, into a shadowy corridor. The sea wind blew through, a thin, eldritch whistling. Caulk looked right and left. The corridor appeared to be empty. For the next hour or so, he would have no magic to conjure up a light. He slipped down the passage, hearing the sea boom and crash through the holes in the ruin. Caulk ran through a maze of passages, seeing nothing except huge pale moths, floating about the ruin like ghosts. The eyes of the sea-hag? Possibly. But they did not seem to be paying any attention to him.