По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

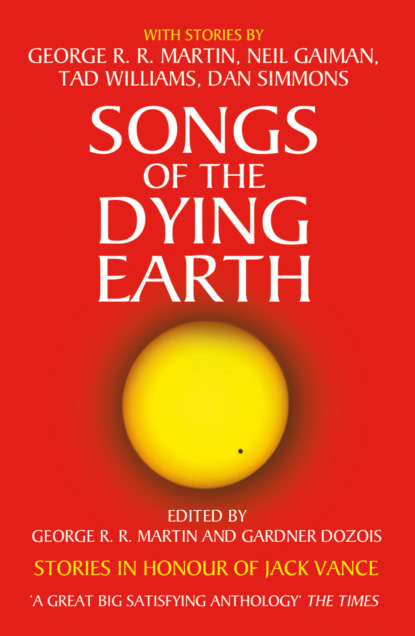

Songs of the Dying Earth

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The two gazed down at Ambius with expressions of superiority mingled with contempt.

“Ambius the Usurper,” said the Exarch, “you are proclaimed outlaw. If you do not surrender your fortress, your person, and your unnecessarily trigger-happy garrison, you will face the wrath of our united armies.”

“I see no reason why I should give you these things,” said Ambius, “when I might offer you instead the pleasure of trying to take them.”

The Basileopater of Pex smiled. “I rather thought that would be your attitude.”

Ambius sketched a bow. “I endeavor to provide satisfaction to my guests,” he said. He bowed again. “Perhaps you worthies would honor me by joining me for dinner tonight, here in the castle. I flatter myself that I set a good table.”

“Out of sensible caution,” said the Basileopater, “I fear we must decline. You gained your present position through treachery to a superior, and we cannot suppose that a usurper’s morals will have improved in the time since.”

Ambius shrugged. “You were so fond of my precursor that you waited a mere thirteen years to avenge him?”

The Exarch inclined his shaved head. “We assumed you would last no longer than your predecessors,” he said. “Though we deplore the efficiency with which you collect tolls that rightfully belong to us, we nevertheless congratulate you on your tenacity.”

“Your mention of tolls brings up an interesting question,” said Ambius. “Assuming that you manage to capture my stronghold, which of you will then occupy it? To whom will the tolls belong, and which of you will have to march home empty-handed? Which of you, in short, will succeed me?”

Ambius, Vespanus knew, had put his finger on the critical point. Whoever controlled the castle would be able to rake wealth out of the Cleft, while whoever did not would have to suffer the loss. Though it was possible that the two commanders had agreed to a joint occupation and a sharing of the wealth, Vespanus couldn’t imagine that two such ambitious rulers would keep such an agreement for very long.

As Ambius asked his question, the Basileopater and the Exarch exchanged glances, then looked down at the Protostrator, their faces again displaying those annoyingly superior smiles.

“Neither of us will occupy the fortress,” the Exarch said.

“You will appoint some third party?” Ambius asked. “How would you guarantee his loyalty?”

“There will be no third party,” the Exarch said. “Once the castle is ours, we will demolish it to the last stone. Each of us shall retire to our toll stations on our respective ends of the Cleft, which shall then be patrolled in order to make certain that Castle Abrizonde is not rebuilt by any new interloper.”

Ambius made no reply to this, but Vespanus could tell by the way he chewed his upper lip that this answer was both unexpected and vexing in the extreme. He could well believe that Ambius understood that he, his fortress, and his fortunes were doomed.

That being the case, Vespanus took the opportunity to secure his own safety.

“My lords!” he called. “May I address you?”

The two rulers looked at him without expression, and made no reply.

“I am Vespanus of Roë, a student of architecture,” Vespanus said. “I was on my way to Occul to further my studies when I passed a night here, and now by chance I find myself under siege. As I have nothing to do with this war one way or another, I wonder if it might be possible to pass the lines and go about my affairs, leaving the quarrel to those whose business it remains.”

The co-belligerents seemed sublimely uninterested in the problems of such as Vespanus.

“You may pass the lines,” the Exarch said, “if you agree to furnish us with complete intelligence of the castle and its defense.”

Vespanus tasted bitter despair. “I can hardly promise such a betrayal of hospitality,” he said, “not in public! The Protostrator would then have every reason to detain me, or indeed to cause me injury.”

The indifference of the two lords was irritating beyond measure.

“That is hardly our problem,” said the Basileopater.

Fury raged through Vespanus. He was tempted to spit at the two rulers, and only refrained because he could scarcely imagine his spittle rising so high.

They had discounted him! In the brief moment in which he had held their interest, they had both derogated him as worthy of no consideration whatever—no threat to their power, no help to the Protostrator, nothing worthy of their attention. Never in his life had he been so insulted.

The two floating lords returned their attention to Ambius.

“You have not taken advantage of our offer of surrender,” said the Basileopater. “We shall therefore commence the entertainment at once.”

At that instant, an ice-blue bolt descended from the sky, aimed directly at Ambius. Without indication of surprise, Ambius raised an arm to display an ideograph graven on an ornate bracelet, and the bolt was deflected into the ground near Vespanus. Vespanus was thrown fifteen feet and landed in an indignified manner, but otherwise suffered no injury. He jumped to his feet, brushed muck from his robes, and directed a look of fury at the two placid lords.

“I note only for the record,” said Ambius, “that it was you who accused me of treachery, but were the first to employ it. I also remark that the employment of an aerial assassin, equipped with Aetherial Boots and a Spell of Azure Curtailment, is scarcely unanticipated.”

The Exarch scowled. “Farewell,” he said. “I trust we shall have no more occasion to speak.”

“I agree that further negotiations would be redundant,” said Ambius.

The illusory sphere brightened again, more brilliant than the old Earth’s dull red sun, and then vanished completely. Ambius searched the sky for a moment, perhaps in anticipation of another flying assassin, then shrugged and walked toward the Onyx Tower. Vespanus scrambled after, anxious to retrieve his lost dignity…

“I hope you are not offended,” he said, “that I attempted to remove myself from the scene of conflict.”

Ambius gave him a cursory glance.

“In our decayed and dying world,” he said, “no one can be expected to act with any motive other than self-interest.”

“You analyze my motives correctly,” said Vespanus. “My interest is in remaining alive—and in repaying those two dolts for their dismissal of me. Therefore I shall throw myself immediately into the defense of the fortress.”

“I await your contribution with breathless anticipation,” Ambius said, and the two ascended the tower.

No further attacks took place that day. Through the tower’s windows, which had the power of adjustment, so that they could view a subject from close range or far away, Ambius and Vespanus watched the two armies as they deployed into their camps. No enemy soldier approached within range of the castle, and, in fact, most seemed to remain out of sight, behind the crests and pinnacles of nearby ridges. Vespanus spent the afternoon trying to cram useful spells into his brain, but found that most were far beyond his art.

As the great bloated sun drifted toward its union with the western horizon, and as the first stars of the Leucomorph began to glimmer faintly in the somber east, Vespanus opened the compartment on his bezeled thumb-ring and summoned his madling, Hegadil.

Hegadil appeared as a dwarfish version of Ambius, clad in the same extravagant blue armor, with a round, vapid face gazing out from beneath the crested helm. Vespanus apologized at once.

“Hegadil has a tendency toward inappropriate satire,” he concluded.

“In fact,” Ambius said, “I had no idea the armor looked to well on me.” He looked at the creature with a critical aspect. “Do you send him to fight the enemy?”

“Hegadil is not a warlike creature,” Vespanus said. “His specialties are construction, and, of course, its obverse, demolition.”

“But if the army is guarded by sorcery…?”

“Hegadil willl not attack the army itself,” said Vespanus, “but rather its immediate environment.”

“I shall look forward to a demonstration,” Ambius said.

Vespanus first sent Hegadil on a whirlwind tour of the enemy camps, and within an hour the madling—reappearing as a caricature of the Basileopater of Pex, a tiny white-haired man dwarfed by his voluminous robes with their blazons and quarterings—gave a complete report as to the enemy’s numbers and deployment. Both armies proved to be larger than Ambius had suspected, and it was with a doomed, distracted air that he suggested Hegadil’s next errand.

Thus it was that, shortly after midnight, a peak overhanging part of the Exarch’s army, having been completely undermined, gave way and buried several companies beneath a landslide. The army leapt to arms and let fly in all directions, a truly spectacular exhibition of firepower that put to shame the morning’s demonstration by the castle defenders.

At the alarm, the army of Pex likewise stood to its arms, though in silence until, a few hours later, a bank of the river gave way and precipitated a part of the baggage train into the ice-laden river, along with all the memrils that had drawn the supplies up the trail. Then the camp of Pex, too, fell into disorder, as soldiers tried to get themselves and their remaining supplies as far from the river as possible. Scores got lost in the dark and fell into hidden ditches and canyons, and some into the river itself.