По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

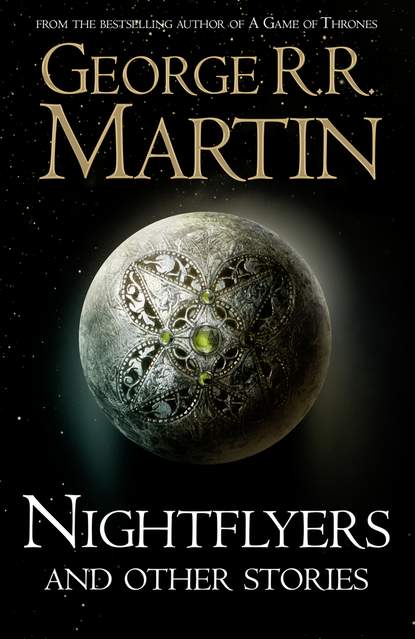

Nightflyers and Other Stories

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“And it can be studied closely on our return,” d’Branin said.

“Which should be immediate,” said Northwind. “Tell Eris to turn this ship around!”

D’Branin looked stricken. “But the volcryn! A week more and we shall know them, if my figures are correct. To return would take us six weeks. Surely it is worth one additional week to know that they exist? Thale would not have wanted his death to be for nothing.”

“Before he died, Thale was raving about aliens, about danger,” Northwind insisted. “We’re rushing to meet some aliens. What if they’re the danger? Maybe these volcryn are even more potent than a Hrangan Mind, and maybe they don’t want to be met, or investigated, or observed. What about that, Karoly? You ever think about that? Those stories of yours – don’t some of them talk about terrible things happening to the races that meet the volcryn?”

“Legends,” d’Branin said. “Superstitition.”

“A whole Fyndii horde vanishes in one legend,” Rojan Christopheris put in.

“We cannot put credence in these fears of others,” d’Branin argued.

“Perhaps there’s nothing to the stories,” Northwind said, “but do you care to risk it? I don’t. For what? Your sources may be fictional or exaggerated or wrong, your interpretations and computations may be in error, or they may have changed course – the volcryn may not even be within light years of where we’ll drop out.”

“Ah,” Melantha Jhirl said, “I understand. Then we shouldn’t go on because they won’t be there, and besides, they might be dangerous.”

D’Branin smiled and Lindran laughed. “Not funny,” protested Alys Northwind, but she argued no further.

“No,” Melantha continued, “any danger we are in will not increase significantly in the time it will take us to drop out of drive and look about for volcryn. We have to drop out anyway, to reprogram for the shunt home. Besides, we’ve come a long way for these volcryn, and I admit to being curious.” She looked at each of them in turn, but no one spoke. “We continue, then.”

“And Royd?” demanded Christopheris. “What do we do about him?”

“What can we do?” said Dannel.

“Treat the captain as before,” Melantha said decisively. “We should open lines to him and talk. Maybe now we can clear up some of the mysteries that are bothering us, if Royd is willing to discuss things frankly.”

“He is probably as shocked and dismayed as we are, my friends,” said d’Branin. “Possibly he is fearful that we will blame him, try to hurt him.”

“I think we should cut through to his section of the ship and drag him out kicking and screaming,” Christopheris said. “We have the tools. That would write a quick end to all our fears.”

“It could kill Royd,” Melantha said. “Then he’d be justified in anything he did to stop us. He controls this ship. He could do a great deal, if he decided we were his enemies.” She shook her head vehemently. “No, Rojan, we can’t attack Royd. We’ve got to reassure him. I’ll do it, if no one else wants to talk to him.” There were no volunteers. “All right. But I don’t want any of you trying any foolish schemes. Go about your business. Act normally.”

Karoly d’Branin was nodding agreement. “Let us put Royd and poor Thale from our minds, and concern ourselves with our work, with our preparations. Our sensory instruments must be ready for deployment as soon as we shift out of drive and reenter normal space, so we can find our quarry quickly. We must review everything we know of the volcryn.” He turned to the linguists and began discussing some of the preliminaries he expected of them, and in a short time the talk had turned to the volcryn, and bit by bit the fear drained out of the group.

Lommie Thorne sat listening quietly, her thumb absently rubbing her wrist implant, but no one noticed the thoughtful look in her eyes.

Not even Royd Eris, watching.

Melantha Jhirl returned to the lounge alone.

Someone had turned out the lights. “Captain?” she said softly.

He appeared to her; pale, glowing softly, with eyes that did not see. His clothes, filmy and out-of-date, were all shades of white and faded blue. “Hello, Melantha,” the mellow voice said from the communicators, as the ghost silently mouthed the same words.

“Did you hear, captain?”

“Yes,” he said, his voice vaguely tinged by surprise. “I hear and I see everything on my Nightflyer, Melantha. Not only in the lounge, and not only when the communicators and viewscreens are on. How long have you known?”

“Known?” She smiled. “Since you praised Alys’ gas giant solution to the Roydian mystery. The communicators were not on that night. You had no way of knowing. Unless …”

“I have never made a mistake before,” Royd said. “I told Karoly, but that was deliberate. I am sorry. I have been under stress.”

“I believe you, captain,” she said. “No matter. I’m the improved model, remember? I’d guessed weeks ago.”

For a time Royd said nothing. Then: “When do you begin to reassure me?”

“I’m doing so right now. Don’t you feel reassured yet?”

The apparition gave a ghostly shrug. “I am pleased that you and Karoly do not think I murdered that man. Otherwise, I am frightened. Things are getting out of control, Melantha. Why didn’t she listen to me? I told Karoly to keep him dampened. I told Agatha not to give him that injection. I warned them.”

“They were afraid, too,” Melantha said. “Afraid that you were only trying to frighten them off, to protect some awful plan. I don’t know. It was my fault, in a sense. I was the one who suggested esperon. I thought it would put Thale at ease, and tell us something about you. I was curious.” She frowned. “A deadly curiosity. Now I have blood on my hands.”

Melantha’s eyes were adjusting to the darkness in the lounge. By the faint light of the holograph, she could see the table where it had happened, dark streaks of drying blood across its surface among the plates and cups and cold pots of tea and chocolate. She heard a faint dripping as well, and could not tell if it was blood or coffee. She shivered. “I don’t like it in here.”

“If you would like to leave, I can be with you wherever you go.”

“No,” she said. “I’ll stay. Royd, I think it might be better if you were not with us wherever we go. If you kept silent and out of sight, so to speak. If I asked you to, would you shut off your monitors throughout the ship? Except for the lounge, perhaps. It would make the others feel better, I’m sure.”

“They don’t know.”

“They will. You made that remark about gas giants in everyone’s hearing. Some of them have probably figured it out by now.”

“If I told you I had cut myself off, you would have no way of knowing whether it was the truth.”

“I could trust you,” Melantha Jhirl said.

Silence. The spectre stared at her. “As you wish,” Royd’s voice said finally. “Everything off. Now I see and hear only in here. Now, Melantha, you must promise to control them. No secret schemes, or attempts to breach my quarters. Can you do that?”

“I think so,” she said.

“Did you believe my story?” Royd asked.

“Ah,” she said. “A strange and wondrous story, captain. If it’s a lie, I’ll swap lies with you any time. You do it well. If it’s true, then you are a strange and wondrous man.”

“It’s true,” the ghost said quietly. “Melantha …”

“Yes?”

“Does it bother you that I have … watched you? Watched you when you were not aware?”

“A little,” she said, “but I think I can understand it.”

“I watched you copulating.”

She smiled. “Ah,” she said, “I’m good at it.”

“I wouldn’t know,” Royd said. “You’re good to watch.”