По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

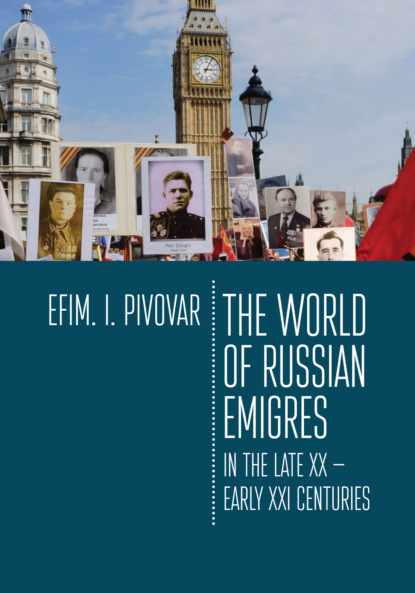

The World of Russian emigres in the late XX – early XXI centuries

Автор

Год написания книги

2021

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

As the role of international supranational organizations will increase in the context of globalization, so will that of institutional structures of the Russian world as an integral part of the global intellectual system. This offers a wide range of opportunities for intellectual and technological modernization of the Russian world, which in the future by all appearances will significantly differ from what it is now, in terms of organization, scientific and information activities, however it will preserve its cultural and mental self-identification with the historical Russian civilization. Without a doubt, new forms of realization and new areas of focus for the Russian world will emerge, and its qualitative characteristics will improve.

Thus, the Russian world in the 21

century is capable of creating new forms and perhaps specific institutional structures of beneficial and adequate transnational interaction that can “fit” Russian historical culture into the global intellectual space and the world system of new geopolitical alliances and associations. In the 21

century, the Russian world institutions will contribute to the greater promotion of Russia’s interests in the new global political and economic system, shaping those structural, informational, and cultural “islands” for the Russian business, culture, science, and society as a whole to rely on.

The present publication presents the author’s reflections on the modern situation in the Russian world and its interaction with Russia and the world civilization in the face of complex geopolitical transformations of the late 20

-early 21

centuries. Among other things, it seems important to study the role of the Russian community abroad in today’s world, to follow up its role in domestic and foreign policy of the Russian Federation over time. In my opinion, evolution of the social and cultural image of Russian-speaking diasporas in the CIS, the Baltic states, and European Union and development of a dialogue with their historical homeland, states and societies in the countries of residence, etc. is another topic of high scientific interest.

At the same time, my intention is to give a personal touch to this work, to reveal the role of the history and culture of the Russian community abroad in my research and academic activities.

The book is intended for scholars of history and other humanities, government officials responsible for interaction with compatriots residing abroad, and the scientific and cultural community of the Russian world itself, as well as all readers interested in the subject of Russian community abroad in the late 20

– early 21

centuries.

Chapter 1

The world of Russian compatriots and national historical consciousness

January 2014 witnessed an important development in the life of the Russian historical community and personally for me as the Head of the Russian State University for the Humanities. Together with other participants of the working group on the preparation of a new cultural-historical standard on history for secondary schools, I took part in a meeting in the Kremlin with the Russian President Vladimir Putin. The Chairman of the Russian Historical Society Sergey Naryshkin, members of the Russian government, heads of historical institutes at the Russian Academy of Sciences, leading university professors of history, history teachers, media, etc. contributed to this discussion. All those present were unanimous in assessing the task facing the historical community as difficult and responsible. In practice, the Concept of a new history standard took considerable effort and generated a lot of controversy that in the end did the Concept a lot of good. ‘Competing history schools are the driver behind new historical knowledge,’ Sergey Naryshkin said.[10 - Transcript of the meeting of Vladimir Putin, President of Russia with the authors of the new history textbook concept. Moscow, the Kremlin. (2014, January 16). Retrieved from http: www.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/200071]

The Kremlin meeting definitely stimulated further work, both because the President thanked the participants for their work and civic position, and above all else because the meeting confirmed at the highest state level some very important principles for history academic courses, i. e. objectivity and impartiality, education aimed at bringing up educated citizens who can think for themselves. Vladimir Putin, in particular, stressed the following:

Unified approaches to history academic courses do not mean public, official, and ideological consensus at all. On the contrary, we mean the common logic of teaching history, understanding the inseparability and interconnection of all stages of the development of our state and our statehood, the fact that the most dramatic and controversial events constitute an integral part of our past. Despite all the differences in assessments and opinions, we should treat them with respect, because this is the life of our people, this is the life of our ancestors, and our national history is the basis for our national identity, cultural, and historical code.[11 - Ibid.]

Back then we also discussed some questions related to certain key dates in the Russian history and their approaching anniversaries. They also needed some balanced approaches to complex historical events and phenomena like the 100th anniversary of World War I, the 70th anniversary of the victory in the Great Patriotic War, the 100th anniversary of the February and October Revolutions. Projects of the Russian History Society, like scientific conferences, exhibitions, new publications concerning the anniversaries of WWI and the Great Victory, the 100th anniversary of the Russian Revolution received wide media coverage both in Russia and in the Russian community abroad. As far as I can judge, the success of all these projects depended on the fact that they promoted a comprehensive range of ideas and images rather than some commonplace official narrative. This created conditions for a positive intellectual dialogue and laid the foundation of the true patriotism, i. e. understanding of all the complexity and unique features of our national history. In many ways, that is why the response of foreign compatriots, representatives of different countries and generations, was so sincere and massive with exhibitions, meetings, and veteran commemoration events taking place all over the Russian community abroad, from New York to Beijing.

Greater focus on history, history science, and education in the Russian society is quite a natural reaction to Russia affirming its status as a world power. Real patriotism in the best sense of the word is inextricably linked to the knowledge and understanding of the history of one’s Fatherland. I firmly believe that patriotic education is education through knowledge about one’s country, its history, and culture of its peoples, and at the same time, about other peoples and civilizations. Such education is designed to develop a broadly educated and cultured individual, including a habit of tolerant perception of ideas and opinions and different historical experience. It is possible to understand events of the pre-revolutionary and Soviet history in different ways, but it is impossible to deny the hard work and the great feat of the peoples of our country, i. e. the feat of overcoming the trials faced by Russian in the 20

century. Those who did this were not some abstract entities but real people, someone’s parents and grandparents. The action “Immortal Regiment,” which triumphantly took place throughout the country and in the Russian community abroad in 2015–2016 and has already become our national tradition, has clearly showed it by addressing the historical memory of thousands of real families. Many students and teachers from Russian universities took part in the “Immortal Regiment” campaign, including the Russian State University for the Humanities, Lomonosov Moscow State University, etc. It is also possible that for some of the younger participants, learning about family history has become the first step towards the profession of a historian.

This principle, education through knowledge, is the foundation of the activities of Russian higher education institutions, including RSUH, the firstborn humanitarian university in the modern Russia. It is based on, in my opinion, the main elements of culture and true patriotism, i. e. national history, Russian literature, the wealth of world languages, cultures, and scientific theories. In this context, a scientific and cultural dialogue with the Russian world abroad has become an intrinsic part of the university life, including projects and events designed to restore the true historical past of Russia. For example, on March 4, 2011, RSUH and the Russkiy Mir Foundation held a scientific conference The Great Reforms of 1861 commemorating the 150

anniversary of the emancipations of serfs in Russia. The University was significantly interested in discussing the modern vision of the issue in the context of shaping the history education concept, including the development of questions for the Unified State Exam on history. Before that, under the auspices of the Moscow Patriarchate and the Russkiy Mir Foundation, there was a conference held in the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour on Great Reforms of Emperor Alexander II as a success story of modernization with the participation of scientists and public leaders from the near and far abroad. It should be noted that the Russian emigre community, especially university and law corporations, laid significant emphasis on the era of the 1860s reforms and saw it as an era of law and civil liberties in the country. Therefore, the intellectual circles in the Russian community abroad paying attention to the history of the Great Reforms in modern Russia was another sign of the unity of historical memory, civilizational community of Russia and the Russian world abroad.

The intellectual heritage of the Russian community abroad has been one of the key elements of the society’s consolidation in creating a new historical consciousness in Russia. It was a consequence of global processes at the turn of the century. The current geopolitical situation has led to the emergence of new trends in the development of world intellectual, information, and cultural processes. The concept of a multipolar world, which is becoming increasingly influential, involves the diversity of civilizations and flourishing national cultures that interact and enrich each other on a constructive basis. Russia’s commitment to these principles of international life was formulated back in 2000 in the “The foreign policy concept of the Russian federation”, which proclaimed Russia’s aspiration “to achieve a multi-polar system of international relations that really reflects the diversity of the modem world with its great variety of interests.”[12 - Concept of Foreign Policy of the Russian Federation. Moscow 2000, June 28 (2004). In A. D. Bogaturov’s (Ed.) Systemic History of International Relations in four volumes 1918–2003, V.4. Documents (pp. 538–539), Moscow.] At the same time, attention to one’s own culture, awareness of one’s unique historical experience and promotion of such values in global media has become one of the prerequisites for strengthening the international influence of a country.

The President of Russia Vladimir Putin in his Address to the Federal Assembly of the Russian Federation in 2018 noted the growing impact of global processes on the economy and culture of all subjects of international politics and the important role of our country in ensuring a positive vector of global development:

This is a turning period for the entire world and those who are willing and able to change, those who are taking action and moving forward will take the lead. Russia and its people have expressed this will at every defining moment in our history.

As Mr Putin stressed, Russia was consistently developing its foreign policy:

… Our policies will never be based on claims to exceptionalism. We protect our interests and respect the interests of other countries. We observe international law and believe in the inviolable central role of the UN. These are the principles and approaches that allow us to build strong, friendly and equal relations with the absolute majority of countries.[13 - Presidential Address to the Federal Assembly (2018, March 1) Retrieved from http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/56957]

Highly intensive global cultural dialogue and informational exchange is also taking place between metropolises and the diaspora across the world amplifying their mutual attraction and interest in each other. Ideas of historical, cultural, and civilizational unity, communicated from the metropolis to the diaspora in the media and on the Internet, art, scientific publications exert significant influence on the public opinion of compatriots in communities abroad by actively engaging them in the international diplomatic and cultural dialogue.

Russia in the early 21

century lays special emphasis on the shaping historical consciousness based on traditional and social values, in particular as a factor of consolidation of the Russian society. It addresses challenges of modernization transit in the context of dramatically increasing global financial, economic, and political competition. In this context, the engagement between Russia and the world of Russian compatriots abroad provides ample opportunities and at the same time contradictions and challenges. They arise from the complex structure and heterogeneity of the Russian community abroad with three main segments: Russian-speaking diasporas of the post-Soviet states (the near abroad); several waves of Russian military, political, and economic emigration in the 1920-1980s and their ancestors (the far abroad). There are also migrants of the 20–21

century from Russia and other territories of the former USSR living in different countries and regions across the world. Formally, the last group is part of the Far Abroad community, but it has some significant social and moral differences from the “old” emigration.

The cooperation with compatriots abroad in the last quarter of a century (from the 1980-1990s) was the most fruitful and intense in terms of shaping the national historical consciousness of the Russians. This experience can be seen as a qualitatively important and unique in the Russian history, when a diaspora that existed in almost complete isolation from the metropolis for several decades has given its historical Motherland a huge cultural heritage filling some considerable gaps in the social, political, intellectual, spiritual, and artistic development of the country.

In the 20

century, Russia went through a tragedy of ideological and informational split with its compatriots abroad. It was based inter alia on fundamentally different vision of the national history and cultural traditions. In the USSR, this resulted in a decisive elimination of many names, events, and facts from the scientific and educational environment that did not ht into the official doctrine of “the history of the USSR in the pre-Soviet period” as well as in totally negative views on the Russian emigration and hushing up its contribution to the global culture. On the contrary, the Russian community abroad developed a cult of the pre-Revolutionary period and underestimated the achievements of the Soviet era in many areas, including economy, science, and culture. Nevertheless, from the very start, the Russian emigre community had an idea for renewing the common historical path and reuniting the divided flows of the “river of time” that embraced the history of Russia in its entirety. The events of the Great Patriotic War have shifted significantly the community’s perception of the post-revolutionary emigration. For many people, patriotism, and love for their homeland lost its retrospectivity and vagueness no longer concerning the old or the imaginary new Russia, but an actual country with its advantages and disadvantages. The Soviet authorities also became more tolerant to the representatives of the post-revolutionary emigration, but the development of the opposition movement among the Soviet intelligentsia, which increasingly took the form of political and religious emigration; the ideological support of the opposition from abroad during the Cold War era became a major new watershed dividing the Soviet Union and Russian community abroad. According to the official Soviet doctrine, their relations could not even be close to the system of “metropolis – diaspora”. The Russia abroad in the 20

century was almost completely excluded from the overall picture of the national history and culture.

In the 1990s-2000s, an intensive multidimensional dialogue between the state, the society of the Russian Federation and the world of foreign compatriots outside the former USSR ensured the restoration of the unity of cultural and historical tradition and the de-ideologization of their images. Gradually, information gaps were filled, and mental contradictions were largely smoothed out, which was facilitated by extensive contacts between Russians and communities of Russian emigrants and their descendants on a personal and public level. Hundreds of scientific publications, articles, numerous publishing and museum projects, ample information on the media convincingly testify to the fact that the legacy of the Russian emigration of the 1920 – mid-1980s has become an organic part of the Russian science and culture. Thus, many values and meanings (from deep inborn knowledge of traditions of the pre-revolutionary era to creative achievements of outstanding Russian intelligentsia in the late 20

century) became a starting point for shaping modern scientific knowledge, education, art, various public initiatives.

The current modernization of the Russian Federation and the search for possible directions of its further historical development are largely related to the adoption of traditional cultural values of the Russia abroad, based on centuries-old cultural foundations. At the same time, a new vision of Russia and Russian history, including a keener and more objective view of the Soviet era and the social and cultural life in the USSR, has emerged in the Russian community abroad.

In the 1990s, the emergence of Russian-speaking communities and their socially and politically difficult life in the young states of the former Soviet republics created a completely new model of relations between the metropolis and the diaspora in the Russian history. This time Russia acted as a focal point for Russian compatriots living in “new foreign countries,” and later, after overcoming its own social and economic problems and regaining international influence, Russia became a champion of their civil rights and cultural and linguistic identity. Migration flows from the CIS and the Baltic States to Russia in the 1990s included a significant number of Russian-speaking migrants who left the territories of the young post-Soviet states due to social and political instability and changing legal status of the Russian language. The adoption of the languages of the title peoples as State languages has become a major challenge for administrative staff, teachers, and higher education teachers, especially the older generation. In addition, the Russian-speaking population was subjected to moral pressure, and, in a number of countries, to direct threats from radical nationalists with the tacit support of some local elites. The result of this process was the exodus of a mass of diploma holders and qualified workers to Russia and the West resulting in smaller number and lower quality of Russian-speaking communities in the near abroad.[14 - O. Zharenova, N. Kechil, E. E. Pahomov (2002) Intellectual migration of Russians: Near and far abroad. Moscow] Later, the young generation of foreign compatriots in the post-Soviet space for the most part chose the integration into the societies of their countries, but many also sought to preserve family traditions, the Russian language. They educated their children in the spirit of the Russian culture, thus being involved in the social life of their diasporas and Russian cultural policy centers abroad. At the same time, the most socially active representatives of Russian compatriots in the CIS countries (entrepreneurs, students, artists) joined the Russian-speaking communities in Western Europe, the USA, Canada, Israel, and Australia. In the 2000s, the majority of institutional structures of the Russian community abroad outside the post-Soviet space were small Russian societies and clubs in large cities, regions or states in different countries based on the principle of association of fellow-countrymen or knowledge of the Russian language. As a rule, they were united in associations within the country. The founder and most active participants were mainly first or second-generation emigrants or citizens of the Russian Federation (as well as of other post-Soviet states) permanently residing abroad. Such associations were most common in those regions of the world where the number of Russian compatriots had increased significantly in recent years, for example in Italy, Spain, Greece, Czech Republic, Bulgaria, Germany, Norway, China, etc. By this time, the 20

century emigrants and their descendants had been strongly assimilated and dissociated with the exception of communities of Russian compatriots in France and the USA. They were the largest centers of Russian emigration, which preserved the system of traditional diaspora structures (military historical societies, Russian schools and youth organizations, church parishes, publishing houses, bookstores, etc.). A key aspect of the institutional development of the modern Russian community abroad was the emergence of various communities on-line. The majority originated from international social media, feedback from readers of e-magazines in Russian, advertising needs of businesses that used the Russian-language Golden Pages and other similar information sources, etc.

The public policy of the Russian Federation on the promotion of the cultural dialogue with the Russian community abroad promotes regular World Congress of Compatriots Living Abroad and the Coordinating Council of Russian Compatriots, as well as the activities of the Russkiy Mir Foundation, Russian diplomatic institutions and representative offices of the Federal Agency for CIS Affairs, compatriots living abroad, and international humanitarian cooperation (Rossotrudnichestvo). The result of these projects was the Russian Centers of Science and Culture operating in the Russian community abroad under the auspices of Russian public and private organizations. They have helped the society of foreign compatriots to bond over their interest in the culture, language, modern life, and traditions of their historical homeland. At the same time, a considerable information space (including the Russian-language foreign press, literature, and the Internet) was filled with a lot of historical documents, memoirs, studies, popular scientific texts, which more and more fully revealed the complex, contradictory nature of historical ways of Russia and Russians in the 20

century. Russian state institutions and public organizations working in the held of cooperation with foreign compatriots have created information portals that allow to develop cooperation and cultural dialogue on a global level.

The key to understanding the essence of modern dialogue between the Russian Federation and communities of foreign compatriots is the ideology of the “Russian World.” The unity of the Russian community abroad and modern Russians is being created, i. e. it is based on a mutual recognition of the common historical past and tolerance toward it. In Moscow, a participant of the 5

World Congress of Compatriots Living Abroad presented the idea of the Russian world as a civilized historical and cultural community:

The Russian world is a planetary space with millions of people creating a Russian identity. And the Russian world does not need any proof of its existence! Here we have Russia with a unique and inimitable inflorescence of cultures of many ethnicities. There we have millions of our compatriots for whom the world without Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky, Tchaikovsky and Rachmaninov, Chaliapin and Hkhvorostovsky, Tupolev and Sikorsky, Rodnina and Kharlamov would be imperfect. The Russian world is a kind of noosphere, so to say, which includes both East and West. Rudyard Kipling once said ‘East is East, and West is West, and never the twain shall meet,” but in Russia, as in the Lobachevskian Geometry, those that cannot meet nevertheless do meet.[15 - Speech by Alexei Lobanov, Director of “Svetoch,” the Orthodox Charitable Society for the Development of Education and Culture in Kazakhstan, ex-chairman of the World Coordination Council at the V World Congress of Compatriots Living Abroad (2015, November 5) Retrieved from http://vksrs.com/publications/vystuplenie-alekseya-lobanova-na-v-vsemirnom-kongresse-sootechestvennikov]

An active promoter of the Russian world concept in the international information space is the Russkiy Mir Foundation and its centres overseas. It is noteworthy that the annual Assemblies of the Russian World are held on November 3, on the eve of the Day of National Unity. The Foundation, whose main task is to support and promote the Russian language worldwide, also implements the principle of moving to the future in line with a continuous historical tradition, focusing on new generations of the international community of the Russian world in all its diversity and uniqueness. Vyacheslav Nikonov, Executive Director of the Russkiy Mir Foundation, speaking at the opening of the Third Assembly of the Russian World in the MSU Intellectual Centre in 2009, said,

The Russian world is not a memory of the past, but a dream of the future of people belonging to a great culture, who are acutely responsive to injustice, who care about notions of honour, service, who are constantly striving for freedom.[16 - Nikonov, V. N. (2010). Not a memory of the past, but a dream of the future. In V. N. Nikonov (ed.) Meanings and values of the Russian world. Collection of articles and materials of the round tables organized by the Russkiy Mir Foundation (4-14). Moscow: Russkiy Mir Foundation.]

The concept of the unified cultural and spiritual space of the Russian world is extremely important for the further development of the domestic and foreign policy of the Russian Federation on compatriots abroad. It has been formulated for quite a long period of time. Obviously, the ideological and cultural gap that existed for decades cannot be bridged overnight. In the 1990s, when the Soviet historiography in Russia was being revised, including the period of the revolution and the Russian civil war, of the topic of the ideological confrontation between the USSR and Russian emigration remained highly politicized among the intelligentsia both at home and abroad. The dialogue with the Russian community living far abroad began to reach a qualitatively new, constructive level, when the Russian intellectual environment, education, and enlightenment systems and mass media established modern approaches to the Russian history which sought to create an objective picture of the historical process through a civilized and tolerant scientific discourse.

The visit of the President of the Russian Federation Vladimir Putin in November 2000 to Sainte-Genevieve-des-Bois Russian Cemetery near Paris was a symbolic step in this direction. The Russian President laid wreaths at the graves of Vika Obolenskaya, a prominent member of the French Resistance movement, and the great Russian writer Ivan Bunin. Standing at the graves of the White movement participants, Vladimir Putin expressed the sentiment that was later widely reported in the press: “We are children of the same mother, Russia, and it’s time for us to unite.” In 2003, during a meeting with representatives of the Russian emigration, again in France, at the Hotel de Ville in Paris, President of Russia Vladimir Putin reiterated that the memory of the tragic events endured by our country should become the basis for joint fruitful work of the Russian nationals and compatriots abroad for the benefit of the future Russia. The same idea was put forward in the opening speech of Vladimir Putin before the participants of the 4

World Congress of Compatriots in Moscow on October 26, 2012:

You share a common concern for Russia’s future and its people, a commitment to be useful to your historical homeland, to promote its socioeconomic development and strengthen its international authority and prestige.[17 - Speech by Vladimir Putin before participants of the World Congress of Compatriots (October 26, 2012). Retrieved from the official website of the President of Russia http://www.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/16719]