По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

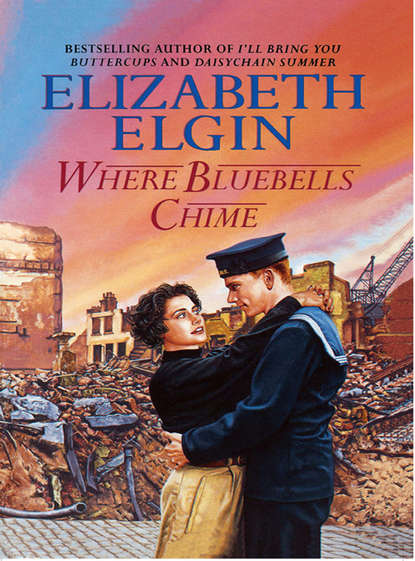

Where Bluebells Chime

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Drew! Don’t go for Ark! Every week, Lord Haw-Haw says the Germans have sunk her!’

‘And every week we know they haven’t. Still, I won’t have a say in the matter. I’m a name and a number for the duration. I do as I’m told. Chiefie in signal school told us to keep our noses clean and our eyes down and we’d be all right. And that’s what I shall do – and count the days to my next leave.’

‘Drew – do you remember how it used to be?’ They had reached the iron railings that separated Rowangarth land from the fields of Home Farm, and stopped to gaze at the shorthorn cows grazing in Fifteen-acre Meadow. ‘It seems no time at all since that last Christmas the Clan was together. Remember? Aunt Julia took a snap of us all. Keth, me, Bas and Kitty and you and Tatty. In the conservatory. We’d all been dancing …’

‘I remember. After that, Uncle Albert started getting a bit huffy about coming over from Kentucky twice a year, but that last summer we were all together was fun, wasn’t it – except for Aunt Clemmy and the fire in Pendenys tower?’

‘And Bas’s hands getting burned. I’m glad Mr Edward had that tower demolished – what was left of it.’

‘Poor Aunt Clemmy. It was an awful way to die. I think, really, it was because she took to brandy after Uncle Elliot was killed. He was her favourite son, Grandmother said. She never got over it. Elliot was her whole life, I believe.’

‘Yes, but I know Mam and Aunt Julia didn’t like him. Even now, if ever his name is mentioned, your mother screws up her mouth like she’s sucking on a lemon. I once heard her say he’d been a womanizer – but we shouldn’t speak ill of the dead, should we, and Tatty hasn’t grown up like him, Mam says. Tatty’s okay.’

‘Yes, but Tatty’s going to have to watch it. You know how strict Aunt Anna can be and Tatty has really fallen for that air-gunner. She said she doesn’t care what happens – nobody is going to stop her seeing him. She’ll have to sneak out, tell lies.’

‘Well, I’m on Tatty’s side. Tim’s a nice young man and someone should remind Tatty’s mam that there’s a war on and that young girls don’t need chaperoning now!’

‘But Tatty’s so innocent, Daiz. She’s always been fussed over and protected. And if Aunt Anna wasn’t fussing, there was always Karl in the background to look after her.’

‘Yes, and teach her to swear in Russian,’ Daisy giggled. ‘Don’t worry about Tatty. She’ll be all right. She’s good fun – away from home. But oh, Drew, I could stand here for ever. It’s all so beautiful I can’t believe there’s a war on.’

The distant sound of aero-engines at once took up her words and made a mockery of them. A bomber flew overhead, big and black and deadly.

‘Looks as if they’re going again tonight.’ Daisy looked up, preparing to count. ‘Take care, Tim,’ she said softly as another aircraft roared over Brattocks Wood. ‘Come home safely, all of you.’

Helen Sutton sat quietly in the conservatory, watching the sun set over the stable block. It tinted the wispy night clouds to salmon pink and shaded the darkening sky to red.

Red sky at night, sailors’ delight …

Rowangarth’s sailor had gone back to his barracks on the noon train from Holdenby. Soon now he should be in barracks, then where? She shivered as the short, sharp pain stabbed inside her chest. In yesterday’s papers she had read that Somewhere in England – They always called a place Somewhere in England when it suited them not to name it – close-packed German bombers with fighter escorts had attacked harbours, fighter stations and naval bases on the south coast.

Naval bases. Plymouth and Portsmouth must surely have been targeted by the Luftwaffe. It was a part, Helen was sure, of the softening-up process so there would be less resistance when the tides were right – right for the Germans, that was. In September.

Where would Drew be then? At sea, Helen hoped fervently. He’d be safer at sea. How proud she had been today of the son Giles never lived to see, tall now, and straight and Sutton fair, with eyes grey as those of his grandfather John; like his great-uncle Edward’s, too.

Drew would come back whole from this war. Fate could not be so fiendish as to take him. Besides, Helen had spoken to Jinny Dobb at the wedding this afternoon, with Jin asking why she was so sad; telling her she was not to fret over young Sir Andrew because his aura was healthy, she insisted, and was Jin Dobb ever wrong, she’d demanded.

‘Take care of yourself, milady,’ she’d urged. ‘He’ll come back safe to claim his own, just see if he doesn’t.’

Dear Jin. Those words gave her brief comfort, Helen smiled, for sure enough, Jinny Dobb could see into the future and read palms and tarot cards – with which she, Helen, did not entirely hold. But this afternoon, at Mary’s wedding, she snatched comfort from Jin’s prophecies and smiled and waved and threw confetti when Will and Mary left Holdenby for a weekend honeymoon in quite a grand hotel in York.

Mary had looked beautiful. Blue certainly suited her and she and Tom walked solemnly down the aisle to where Will and Nathan waited. How nice, those cosy country weddings.

The door knob turned, squeaking, and Tilda walked softly to Helen’s side.

‘I’ve brought your milk and honey, milady. Miss Julia asked me not to forget it.’

‘Tilda, you shouldn’t have bothered, especially as you’ll be managing alone until Mary gets back. You’ll have all your work cut out –’

‘Oh, milady, I’ll be right as rain. There’s only you and Miss Julia and the Reverend to see to and not one of you a bit of bother. It was a grand wedding, wasn’t it, though I gave up thinking long ago that anyone’d ever get Will Stubbs down the aisle. But fair play, Mary managed it though no one can say those two rushed headlong into wedlock, now can they?’

‘Tilda!’ Helen scolded smilingly. Then raising her glass she took a sip from it. ‘And here’s wishing them all the happiness in the world!’

‘Amen to that.’ Tilda turned in the doorway. ‘You’ll think on, milady, not to forget and switch the light on?’ An illuminated conservatory would fetch every German bomber on the Dutch coast zooming in over Rowangarth and would land them with a hefty fine and a severe telling-off from the police for doing such a stupid thing.

‘I’ll remember. I think you’d better remind me tomorrow to ask Nathan to take the light bulb out.’ A conservatory was too big and awkward to black out effectively. Best take no chances. ‘And don’t wait up. Goodness knows when the pair of them will be back from Denniston. They have a key. You’ve had a long day – off to bed with you.’

And Tilda said she thought she could do with an early night, but that she would see to the doors and windows first, then check up on the blackouts.

‘Good night, milady,’ she smiled, closing the door softly behind her.

Dear Lady Helen. They would have to take good care of her for there were few left from the mould she’d been made from; precious few, indeed.

Tom Dwerryhouse hung up his army-issue gas mask, took off his glengarry cap, then leaned the rifle in the corner.

There had been an urgent parade of the Home Guard called for this evening and he and several others had had to leave the wedding early and put on their khaki for a seven o’clock muster.

It was a relief to be told that their rifles – ammunition, too – had arrived at last and he opened the long, wooden boxes only to sigh in disbelief. Those long-promised rifles – and he knew it the minute he laid eyes on them – were leftovers from the last war and had lain, it seemed, untouched and uncared for in some near-forgotten store.

He took the rifle, breaking it at the stock to squint again down the barrel. Filthy! It would take a long time to get the inside of that barrel to shine like it ought to. There would have to be a rifle inspection at every parade to let them know that Corporal Dwerryhouse wasn’t going to allow any backsliding when it came to the care of rifles, old and near-useless though they were.

He snapped it shut, gazing at it, remembering against his will when last he fired such a rifle. It was something he would never forget. He knew the exact minute he took aim, awaiting the order to fire. And his finger had coldly, calmly, squeezed the trigger that Épernay morning.

It was the bullet from his own rifle, he knew it, that took the life of the eighteen-year-old boy. Aim at the white envelope pinned to the deserter’s tunic to show them where his heart was, that firing squad had been told. But the other eleven men had been so uneasy, so shocked that he, Tom Dwerryhouse, took it upon himself to make sure the end would be quick and clean.

A sharpshooter, he had been, but an executioner they made him that day. Refuse to take part and he too would have been shot for insubordination and another, less squeamish, would have taken his place.

Then, directly afterwards, the shelling started and heaven took its revenge for the execution of an innocent and directed a scream of shells on to that killing field so the earth shook. That was when he fell, surrendering to a blackness he’d thought was death.

Rifleman Tom Dwerryhouse did not die in that Épernay dawn. He awoke to stumble dazed, in search of the army camp he did not know had been wiped out by the German barrage.

How long he walked he never remembered, but a farmer had taken him in and given him food and shelter and civilian clothes to work in. And Tom acted out the part of a shell-shocked French soldier, and those who came to the farm looked with pity at the poilu who was so shocked he uttered never a word.

The Army sent a letter to his mother, telling her he had been killed in action and his sister wrote to the hospital at Celverte, to tell Alice he was dead.

The night of that letter, Alice was taken in rape. She had not fought, she told him, because she too wanted to die, but instead she was left pregnant with the child who came to be known as Drew Sutton.

Now white-hot anger danced in front of Tom’s eyes. He flung the rifle away as though it would contaminate him and it fell with a clatter to the stone floor.

He hoped with all his heart he had broken it.

9 (#ulink_a8ad30cf-e018-5234-871f-4cf41a5c30a3)

Tom stood hidden, unmoving. To a gamekeeper, stealth was second nature. Such a man must move without the snapping of a twig underfoot, learn to sink into night shadows or merge into sunlight dapples. It was, in part, to ensure that young gamebirds were not disturbed nor frightened unduly, but mostly that inborn stealth helped outwit poachers, out to take pheasants or partridge.

The sudden clicking of a rifle bolt was a sound he remembered well. Breath indrawn, he awaited the command he knew would follow.

‘Halt! Who goes there?’