По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

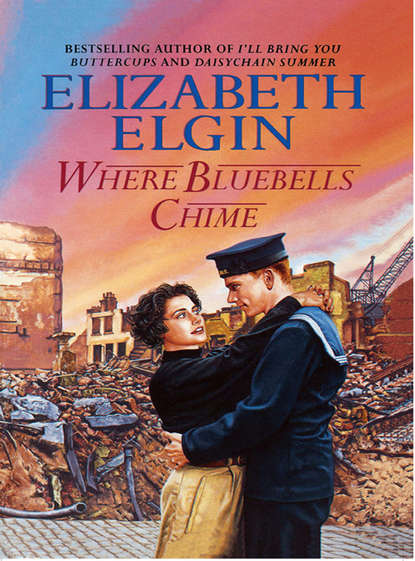

Where Bluebells Chime

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

But things were bad: the French overrun and British soldiers snatched off Dunkirk beaches reeling with the shock of it. It was all on account of that Maginot Line, Tom considered gravely. Smug, the French had been. No one would ever breach their defences; not this war.

But they hadn’t reckoned with Hitler’s cunning in invading the Low Countries. Never a shot fired in anger, because his armies had just marched round the end of the invincible Maginot Line and had been in Paris before the French could say Jack Robinson. Only Hitler could have thought of pulling a fast one like that and getting away with it. A genius was he, or mad as they come?

Tom reached again for his tobacco. He needed a fill. Things were writhing inside him that only a pipe could soothe. It wasn’t just the invasion and taking care of Alice and Daisy and Polly, if it happened; it was that Local Defence lot in the village. He had left Keeper’s Cottage expecting to join it and be treated with the respect due to an ex-soldier, but all they’d done was witter amongst themselves, tie on their Local Defence Volunteer armbands and agree to meet another night. And there was nothing like an armband for scaring the wits out of a German Panzer Division!

‘That you, love?’ He half turned as the back door opened and shut.

‘It’s me, Dada. Mam not home, yet?’

‘No, lass. She rang up from the village, summat about getting the loan of a tea urn. Be about half an hour, she said.’

‘I’d better see to the blackout, then. Won’t take me long, then I’ll put the kettle on.’

Daisy had expected both her parents to be home; had got herself in the mood to come out with it, straight and to the point. That Mam still wasn’t back had thrown her.

She pulled the curtain over the front door then walked upstairs, drawing the thick black curtains over each window. She should have asked Dada, she brooded, how long ago Mam had phoned. She was getting more and more nervous. If Mam wasn’t soon home, she’d have to blurt her news out to Dada and she didn’t want to do that.

Mind, she was glad they had a telephone at last. They wouldn’t have got one if it hadn’t been for the coming of the Land Army, and them taking over Rowangarth bothy. Aunt Julia had been glad for the land girls to have the place because since the apprentices who lived there had been called up into the militia it had stood empty, and Polly living there alone, rattling round like a pea in a tin can.

The Land Army people had had so many requests from the local farmers for land girls to help out, and Rowangarth bothy would be ideal quarters for a dozen women. A warden would be installed to run the place and a cook, too. Aunt Julia had said they could have it for the duration with pleasure if they would consider Mrs Polly Purvis as warden or cook. Mrs Purvis had given stirling service, Aunt Julia stressed, looking after the garden apprentices, and would be ideally suited to either position.

So Keth’s mother was offered the cooking, and accepted gladly, especially when they’d mentioned how much wages she would be paid, as well as her bed and keep. And the GPO came to put the phone in.

That was when the engineer had asked Dada, Daisy recalled, why he didn’t get a phone at Keeper’s Cottage whilst they were in the area.

‘There’ll be a shortage of telephones before so very much longer, and that’s a fact,’ the GPO man said. ‘Soon you’ll not be able to get one for love nor money. The military’ll have taken the lot!’

Daisy could have hugged Dada when he said yes and now a shiny black telephone stood importantly in the front passage at Keeper’s Cottage.

For the first week, Mam had jumped a foot in the air every time it rang because Aunt Julia was tickled pink that Keeper’s was on the phone at last and rang every morning for a chat. And she, Daisy, so often sat on the bottom step of the stairs, gazing at it, willing it to ring so that when she lifted it and whispered ‘Holdenby 195’, Keth would be on the other end, calling from Kentucky and he’d say –

But Keth couldn’t call and she couldn’t call Keth, not even if she didn’t mind giving up a whole week’s wages just to talk to him for three minutes, because civilians weren’t allowed to ring America now. The under-sea cable was needed for more important things by the Government and the armed forces. Indeed, civilians were having a bad time all round, Daisy brooded. Asked not to travel on public transport unless their journey was really necessary; their food rationed, clothes so expensive in the shops that few could afford them, and no face cream nor powder nor lipstick to be had – even a shortage of razor blades, would you believe? But that was as nothing compared to what was soon to come, she thought as she pulled down the kitchen blind, drew together the blackout curtains then pulled across the bright, rose-printed curtains to cover them, because not for anything was she looking at those dreary black things night after night, Mam said.

‘Shall I make a drink of tea, Dada?’ Daisy switched on the light.

‘Best not, sweetheart. Wait till your mam gets back.’

Since tea was rationed six months ago, the caddy on the mantelshelf was strictly under Alice’s supervision.

‘Dada?’ Daisy sat down in the chair opposite. ‘There’s something –’ She stopped, biting on the words.

‘Aye, lass?’ Her father did not shift his gaze from the empty fireplace and it gave her the chance she needed to call a halt to what she had been about to say.

‘I – well, I know it’s stupid to ask, but can you tell me,’ she rushed on blindly, warming to her words, ‘what will happen to my money if the Germans invade us? Will I get it?’

‘Well, if you wait another year till you’re one-and-twenty, you’ll know, won’t you? Not long to go now, so I wouldn’t worry over much. But if you really want my opinion, that inheritance of yours is going to be the least of our worries if the Germans do get here. So let’s wait and see, shall us?’

Daisy’s inheritance. Money held in trust by solicitors in Winchester. Only a year to go and then it would be hers to claim, Tom brooded – if the Germans didn’t come, that was; if all of them lived another year.

‘Silly of me to ask.’ And silly to have almost blurted out what she had done yesterday, during her dinner hour. ‘You’re right, Dada. Either way now, it doesn’t matter.’

And it didn’t, when Drew was in the Navy and Keth was in Kentucky not able to get home, and people having to sleep in air-raid shelters and already such terrible losses by all the armed forces. When you thought about that, Daisy Dwerryhouse’s fortune was immoral, almost.

It came as a relief to hear the opening of the back door and her mother calling, ‘Only me …’

Then Mam, opening the kitchen door, hanging her coat on the peg behind it, patting her hair as she always did, popping a kiss on the top of Dada’s head like always.

‘Sorry I’m late, but I’d the offer of the use of a grand tea urn for the canteen. And talking of tea, set the tray, Daisy, there’s a love.’

She sat down in her chair, pulling off her shoes, wiggling her toes.

Then, as she put on her slippers Daisy said, ‘Mam, Dada, before we do anything – please – there’s something I’ve got to tell you …’

2 (#ulink_4a2ad59a-120f-5c29-9191-2f226d23e0eb)

‘Tell us?’ Tom gazed into the empty fireplace, puffing on his pipe, reluctant to look at his daughter. ‘Important, is it?’ Which was a daft thing to ask when the tingling behind his nose told him it was. Loving his only child as he did, he knew her like the back of his own right hand.

‘Anything to do with the shop?’ Alice frowned.

‘Yes – and no. I don’t like working there, you know.’

‘But whyever not, lass?’ Tom shifted his eyes to the agitated face. ‘You’ve just had a rise without even asking for it.’

‘Never mind the rise – it’s still awful.’ Daisy looked down at her hands.

‘Oh, come now! Morris and Page is a lovely shop, and the assistants well-spoken and obliging. All the best people go there and it’s beautiful inside.’ Twice since her daughter went to work there, curiosity got the better of Alice and she had ventured in, treading carefully on the thick carpet, sniffing in the scent of opulence. She bought a tablet of lavender soap on the first occasion and a remnant of blue silk on the second. Paid far too much for both she’d reckoned, but the extravagance had been worth it if only to see what a nice place Daisy worked in.

‘I’ll grant you that, Mam. The shop is very nice, but once you are in the counting house where I work, there are no carpets – only lino on the floor. And we are crowded into one room with not enough windows in it. And as for those ladylike assistants – well, they’ve got Yorkshire accents like most folk. A lot of them put the posh on because it’s expected of them. And obliging? Well, they get commission on what they sell and they need it, too, because their wages are worse than mine!’

‘So what’s been happening? Something me and your dada wouldn’t like, is it?’

‘Something happened, Mam, but nothing that need worry anyone but me. Yesterday morning, if you must know. There was this customer came to the outside office, complaining that we’d overcharged her. She gets things on credit, then pays at the end of the month when the accounts are sent out. Anyway, yesterday morning she said she hadn’t had half the things on her bill, so I had to sort it out. She was really snotty; treated me like dirt when I showed her the sales dockets with her signature on them.’

‘But accounts are nothing to do with you, love. You’re a typist.’

‘I know, Mam, but the girl who should have seen to it is having time off because her young man is on leave from the Army, so there was only me to do it.’

‘So you told this customer where to get off, eh?’ Tom knew that flash-fire temper; knew it because she had inherited it from him.

‘As a matter of fact, I didn’t. I just glared back at her and she said I was stupid and she’d write to the manager about me, the stuck-up bitch!’

‘Now there’s no need for language!’ Alice snapped. ‘But if you didn’t answer back nor lose your temper, what’s all the fuss about?’

‘Oh, I did lose my temper, but I didn’t let that one see it. When she’d slammed off, I realized it was my dinner break, so I got out as fast as I could. She got me mad when there are so many awful things happening and all she could find to worry about was her pesky account!’

‘But you cooled down a bit in your dinner break?’

‘Well, that’s just it, you see.’ Daisy swallowed hard. No getting away from it, now. ‘I ate my sandwiches on a bench in the bus station, then I walked into the Labour Exchange and asked them for a form. And I filled it in. I’m changing my job. I’m not kowtowing any longer to the likes of that woman.’