По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

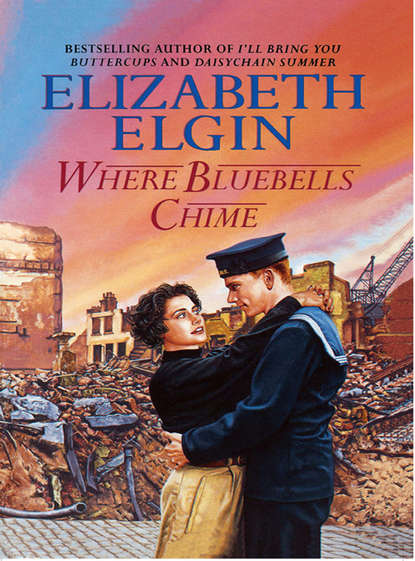

Where Bluebells Chime

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Packed to overflowing it had been with soldiers with respirators and kitbags, airmen with kitbags and respirators and a great many sailors with the added encumbrance of rolled and lashed hammocks and all of them sleeping and snoring not only where they ought to have been, but in corners, corridors and anywhere space was to be found.

‘We were held up at Newcastle for almost an hour and if it hadn’t been for an ATS girl, I don’t know what I’d have done – you know what I mean …?’

No need to go into intimate detail, but the resourceful young lady had left the train, marched up to the engine driver and loudly threatened, ‘Now listen ’ere, mate! If you start your bleedin’ engine before me and this lady have found somewhere to have a widdle, I’ll burst yer!’ To which the driver replied that it looked as if they’d have time to sit there for the rest of the night and make their Wills if they were so minded, before he got the green light to move.

So embarrassing it had been and surely obvious to everyone awake that they were about to search the blacked-out railway station for the ladies’ room!

‘But wasn’t there a lavvy on the train?’ Tilda quickly sized up the cause of the upset.

‘There were several, and all of them filled with luggage.’ If she could have reached one, that was. They’d had the greatest difficulty getting off the train and they had struggled and pushed their way back to their compartment only to find their seats occupied by two burly sergeants who gazed at the ATS girl’s single stripe and told her where she could go. Pulling rank, Miss Clitherow later discovered it was called, and bleedin’ sergeants were always doing it!

‘And the train was dirty and blacked out.’ Except for the odd blue light bulb, that was, and if she never set foot on a train again for the entire duration of hostilities, it wouldn’t bother her one iota. And that, she supposed was something of a contradiction in view of the decision she had made.

‘Never you mind, Miss Clitherow, dear. Just take off your hat and wash your hands, then I’ll pour you a cup.’ Tilda had never seen the housekeeper so distraught, not in all her thirty-odd years at Rowangarth. ‘And then I’d get a bath, if I were you, and pop straight into bed.’

‘Oh, no!’ A bath maybe, but she must see her ladyship as soon as maybe, thank her for the time off, then explain the position fully, a thought which brought tears to her eyes and Tilda to place a comforting arm around her shoulders – a liberty she would once never have dreamed of taking – and tell her that she was home and safe now, and must never go away again. Which immediately caused the tears to flow faster and for Miss Clitherow to murmur, amid gasps, ‘Tilda! Please don’t say that!’

The tears came again when she and her ladyship were comfortably seated in the small parlour, windows wide to the July afternoon. It was her ladyship’s fault, the housekeeper reluctantly admitted, her being so genuinely pleased to see her back from her bereavement.

‘We have missed you, Miss Clitherow,’ Helen smiled. ‘It’s so good to see you again. Julia tells me your journey was very uncomfortable, but never mind – you are home now.’

‘Oh dear, Lady Helen, but I’m not you see. Well, not for so very much longer.’

And she had gone on to explain how her cousin Margaret – the elder sister of Elizabeth, whose funeral Miss Clitherow had gone to attend – had begged her, almost, to leave domestic service and spend her remaining years close to kin amid the beautiful – and safe – hills and lochs of Scotland. ‘It’s time for you to retire, stop working for the gentry, Agnes, my dear. And it’s so peaceful and quiet, here.’

Her cousin was right, of course. Apart from the blackout, there was little sign of the war in the tiny village between Oban and Connel. Just sight of the ferry from Achnacroish to Oban and the odd merchant ship making for the Sound of Mull. Certainly there were no aircraft armed with bombs and bullets, their wings heavy with fuel, struggling to take off. The bombers from RAF Holdenby Moor worried Agnes Clitherow. She flinched when they roared overhead, awoke with a start when, in the early hours of the morning, they returned from raids over Germany.

‘We are safer here on the west coast. If the invasion comes it will be from the south or the east,’ Margaret had urged and she was right without a doubt. Hitler’s divisions occupied France, Belgium and the Netherlands, had ports and aerodromes there in plenty. ‘Mark my words, Agnes, Hitler will not do the obvious. They are waiting for him to invade the south coast of England but in my opinion he’ll land in Yorkshire or Northumberland. He’s a sly one!’

‘Not for so very much longer?’ Helen’s words cut into the housekeeper’s troubled thoughts. ‘You aren’t ill, Miss Clitherow?’

‘No, milady, but I am getting older, and my cousin has offered me my own room. It’s so peaceful there in Scotland, and safe somehow.’

‘And you don’t feel safe here at Rowangarth?’ Helen Sutton knew how much her housekeeper disliked having the aerodrome so near. ‘You really want to go, Miss Clitherow? Are you and I to part after so long?’

‘Needs must, Lady Helen. You know how old I am and I’m mindful of the fact that there would always have been shelter for me here. But I’m of a mind to end my days with Margaret in Scotland. It’s why I’m giving notice now, and hoping it will be convenient for me to go in four weeks’ time.’

‘Miss Clitherow, you may leave as soon as you wish, but it will grieve me to see you go. I shall miss you greatly. Rowangarth will miss you.’

‘Oh, milady …’ Tears trembled on Agnes Clitherow’s voice.

‘Now don’t upset yourself,’ Helen soothed. ‘Scotland isn’t the other end of the world. We’ll all keep in touch. But promise me one thing? You know I wish you well in your retirement, but just if things don’t work out, I want you to know that you have only to ring me. There is room and to spare for you always here at Rowangarth. You’d never be too proud to admit that you missed us more than you thought, now would you?’

‘No. I wouldn’t,’ she sniffed. ‘This house has been like a home to me and where else would I turn, if trouble came? And like you say, Rowangarth is only a telephone call away. But if you’ll pardon me, milady – things to be done, you see …’ And if she didn’t get out of this dear little room she would break down and weep – a thing she had never done before – well, not in front of her ladyship, that was. ‘Perhaps if we could talk later? It has been distressing for me, telling you.’

‘And for me, too, learning I am to lose a splendid housekeeper and a dear friend. But if your mind is truly made up, then I promise not to try to persuade you to stay.’

‘Thank you. Thank you for everything, milady,’ the housekeeper choked as, for the first time in all her years with Lady Helen, she made a hasty, undignified exit.

Helen watched her go, heard the quiet closing of the door and the slow, sad steps along the passage outside, walking away from her.

But everything and everyone she had known and loved seemed to be leaving her now, she thought sadly. Soon there would be no one left. No one at all.

Jack Catchpole, son of the late Percy, and head – and since war started the only – gardener at Rowangarth, was not at all sure about the land girl Miss Julia had said would be coming. To help in the kitchen garden, she said, since they must grow all the food they could. Vegetables and fruits in season would help the war effort and Rowangarth, therefore, was entitled to apply for help from the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries – the Ag and Fish, most people called it.

What had surprised Catchpole, however, was that as in most things, Miss Julia had had her way in no time at all and now he must prepare himself for a female invasion of his domain.

He sucked on his empty pipe, contemplating the horrors of it. For one thing, she wouldn’t know a weed from a seedling and for another, she wouldn’t want to get her hands dirty nor break her fingernails which without a doubt would be long and painted bright red. And she would be late every morning, an’ all, and make up all kinds of female excuses when she wanted time off to meet her young man or have her hair permanently waved. In short, she was not welcome.

It came as a great surprise, therefore, and something of a shock to see a young woman, smartly dressed in Land Army uniform, advancing upon him just as the kettle on the potting shed hob was coming to the boil and he had emptied his twist of tea leaves and sugar into the little brown teapot he had used for years and years. He watched her, saying not a word until she stood before him, eyes wide.

‘Are you the head gardener?’ she asked.

‘Aye.’ His eyes did not waver.

‘I think you’re expecting me, sir. I’m your land girl and I’m willing to learn …’ She let go her breath in a little nervous huff.

‘Aye.’ Catchpole stuffed his pipe into the pocket of his shirt. ‘Well, the first thing you learn in my garden is not to call me sir. My name is Jack Catchpole – Mister Catchpole to you. And what might your name be?’

‘Grace Mary Fielding, Mr Catchpole, but people call me Gracie. Gracie Fielding – Gracie Fields, see? Well, when you come from Rochdale, what else?’

‘What else indeed?’ Catchpole liked Gracie Fields and her happy, brash voice. Made him laugh, Our Gracie did. ‘So, young Gracie Fielding, what made you choose market gardening in general and Rowangarth in particular?’

‘Oh, I didn’t, Mr Catchpole – choose either, I mean. I just got sick of streets and mills and joined the Land Army so I could be in the country – and do my bit, of course. And it was the Land Army chose to send me here.’

‘Mills, eh? Cotton mills?’

‘Mm. All the women in our family worked in the mills, but Mam said she wanted better for me. “Gracie isn’t going in t’mill,” she said and she worked extra hours to send me to the Grammar School.’

‘So you got yourself a better job – kept away from the looms, then?’

‘A better job – yes,’ she grinned, ‘but at the mill, as a wages clerk. Would make Dickie Hatburn’s cat laugh, wouldn’t it?’

‘And who might Dickie Hatburn be?’

‘Dunno, but he must have had a cat, that’s for sure.’ She threw back her head and laughed and her teeth were white and even. Her eyes laughed, too.

‘Do you like cats, Gracie Fielding?’

‘Not as much as dogs.’

‘Then that’s the second thing you learn in my garden. Cats is not welcome. When you see one you chase it, don’t forget. Cats wait till you’ve made a nice soft tilth and sown your seeds careful, like, in nice straight rows, then they’ve the cheek to think you’ve done it specially for them. Soon as your back is turned, they’re scratching about among your little seeds and you know what they leave behind them?’

‘Oh I do, Mr Catchpole, and I’ll chase them.’

‘And dogs, too. Dogs’re not welcome in my garden either, unless accompanied by a responsible adult and secure on the end of a lead.’

‘I’m learning,’ Gracie smiled.