По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

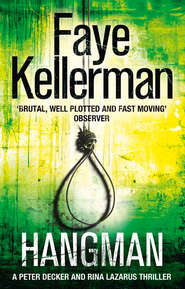

Peter Decker 2-Book Thriller Collection: Blindman’s Bluff, Hangman

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“Yes, I am. In a few years, I’ll be away at college and then you won’t have anyone to cook for anymore. You’ll miss these days.”

“I have your father.”

“He’s never home, and half the dinners you cook for him wind up in the warming drawer. Why do you bother?”

“Someone sounds resentful.”

“I’m not resentful, I’m just stating fact. I love Abba, but he just isn’t home very much.” She bit her thumbnail. “Is he going to make it to my choir performance tonight?”

“Your performance is tonight? I thought it was tomorrow.”

“Oh, Mrs. Kent changed it. I forgot to tell you.”

“If your performance is tonight, Hannah, are you even going to eat dinner at home?”

“No, I guess not,” Hannah said. “Is Abba going to make it?”

“He’s made it to your last two performances. I’m sure he’ll be there …” She thought about the morning news. “Unless something dire comes up.”

“Something dire like murder?”

“Murder is very dire.”

“It isn’t really. What difference does it make? The person’s already dead.”

It was clear that Hannah was in her own narcissistic world. There was no use in trying to reason with her. Instead, Rina changed the radio station to oldies. The Beatles were singing about eight days a week.

“I love this song!” Hannah turned up the volume knob and sat back contentedly, eating her bagel, humming along while tapping her toes.

All resentment toward her father seemed to have dissipated.

The attention span of a gnat was sometimes a good thing.

Walking into the courtroom, he was glad he’d taken extra time to make sure his tie was properly knotted and his shirt collar had the right amount of starch. With his shoulders erect and a jaunty stride, he owned the world.

He had a gift.

Like a composer with perfect pitch, he had what he called perfect sound. Not only could he translate words and decipher speech—the minimum requirements for his job—but equally as important, he could code nuances and know everything about that person’s background, often after just a few sentences. He could tell where the person grew up, where the person’s parents grew up, and where the person was currently residing.

Of course, he could discern simple things like race and ethnicity, but who among the living could also zero in on social class and educational level in a single breath? How many fellow human beings could detect whether the person was happy or sad—no biggie there—but also whether he or she was angry, peeved, jealous, annoyed, wistful, sentimental, considerate, empathetic, industrious, and lazy? And not by what they said, but how they said it. He could distinguish between nearly identical regional American accents, and he had a magic ear for international accents, too.

In his world, there was no need for visuals. The eye was a deceptive thing. He’d been given an otherworldly gift, not to be squandered on trivial things like a parlor game.

Name that accent.

People were such assholes.

His PDA buzzed. He fished it out of his pocket and pushed a well-worn button. The machine read the text message aloud in a staccato electronic voice: “See U for usual lunch.” He turned off the handy-dandy portable and stowed it back in his pocket. The time was twelve-thirty, the place was a sushi bar in Little Tokyo, and the date was Dana.

The day was shaping up to be a good one. Taking his seat on the bench, he adjusted his designer sunglasses, turned his head in the direction of the jury box, and flashed the good citizens of Los Angeles a blinding smile of perfectly straight white teeth.

Showtime!

After receiving instructions from the judge not to talk about the case, the jury filed out of the courtroom.

The woman in front was named Kate and that’s all that Rina knew about her. She looked to be in her thirties with pinched features, clipped blond hair, and hoop earrings dangling from her earlobes. She turned to Rina and said, “Ally, Ryan, and Joy are going to the mall. You want to join us for lunch?”

“I brought a sack lunch, but I’d love to sit with you. Anything to get out of this building.”

“Yeah, who’s really in jail?” Kate smiled. “I’m going to use the little girls’ room, and Ryan and Ally have to make a couple of phone calls. We’re all meeting outside in about ten minutes.”

“Sounds good.” As Rina pushed open one of the double glass doors of the criminal courthouse, a blast of furnace air hit her face, and the roar of traffic filled her ears. The asphalt seemed to be melting with heat waves shimmering in the smog. The only shade in the area was provided by the multistory buildings—not much shadow in the noonday sun—and a row of hardy trees that seemed pollution resistant.

She dialed Peter’s cell expecting to leave a message. She was delightfully surprised when he picked up.

“How’s it going?” she asked.

“I’m still alive.”

“That’s a good thing. Where are you?”

“I’m with Sergeant Dunn and we’re headed for St. Joseph’s hospital intensive care unit. Gil Kaffey is out of surgery.”

“That’s good news. I read the story this morning, although I’m sure it’s out of date already. You’ve got your hands full.”

“As always.”

“I love you.”

“I love you, too.”

“Am I going to see you anytime soon?”

“Eventually I’ll have to sleep.”

“Do you think you’ll make it to Hannah’s choir recital?”

A pause. “When is it again? Tomorrow at eight?”

“It’s actually tonight at eight. The choir teacher changed the date and Hannah forgot to tell me.”

“Oh boy.” Another pause. “Yes, I will make it; however, I will not vouch for my appearance or my hygiene.”

Rina felt relieved. “I’m sure that all Hannah wants is to see your face.”

“That will happen. Just do me a favor. Poke me in the ribs if you see my eyes start to close. How’s it going over there in beautiful downtown L.A.?”

“Summer is upon us.” She wiped sweat off her forehead with the back of her hand. “I shouldn’t have worn my sheytl today. It’s too hot for a wig.”