По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

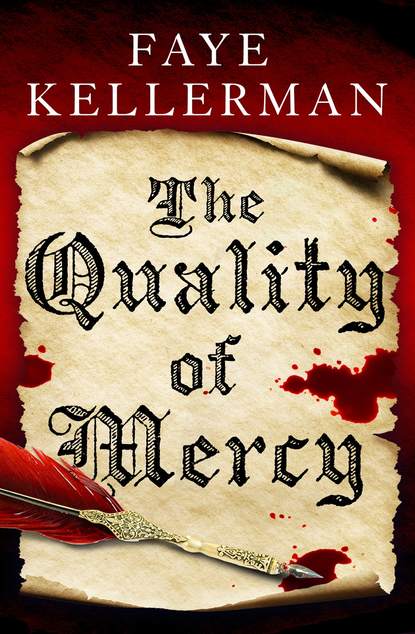

The Quality of Mercy

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“When you had no one to turn to, twas Harry—”

“I know,” Shakespeare interrupted. “What would you like me to do?”

“Find this fiend,” Margaret announced.

She stated it so simply, as if it were the only agenda open to him.

“I suppose I could take a brief trip up North,” Shakespeare said. “Make a few inquiries … Although without Harry, the fellowship is sadly lacking competent players. And the theaters have just reopened—”

“If the fellowship can go on without Harry, production can proceed without you. Find my husband’s murderer!”

Shakespeare said he’d try, though his stomach had become knotted at the thought. He would depart in a few days.

Margaret whispered breathlessly, “Hints are that the killer is well versed in the Italianate style of dueling. The rapier’s thrust cut deep into Harry’s heart.”

“Then the murderer must have been very adroit,” noted Shakespeare. “Harry was a fine swordsman.”

“Yes,” Margaret answered in a small voice. “Precaution, Will. Be clever or you’ll find your fortune as Harry’s.”

“I shall step lightly,” Shakespeare said. For a moment, he wondered how she had ensnared him to do her bidding. But deep in his heart he knew that she really didn’t talk him into anything. Shakespeare wanted to avenge his mentor. He also knew that had the situation been reversed, Harry would have done the same for him. “If I find this Hell-rot scum, I shall be well prepared.”

“And I shall love you all the more for my Harry’s revenge.” Margaret’s face had become alive with the desire for retribution. “God bless you, Will Shakespeare. An honorable man, you are.” Margaret kissed his cheek and dropped his hand. “I must rejoin my children and friends. You’ll keep me informed?”

“Of everything I disclose.”

“I wish you luck, William.” She let down her veil, tightened her cloak, and hurried away.

Cuthbert waited for Shakespeare at the mouth of the open road. The overcast had started to lift, giving way to the green velvety hillside, a smooth verdant wave speckled with silver brush, ancient oaks, wildflowers, and the white nap of unshorn sheep. Taking a deep breath, he tried to exhale slowly, but instead let out a hacking cough. He cleared his lungs, spat out a large ball of phlegm and flexed his stiffened fingers. His eyes swelled with water and he blew his red, round nose.

Bells from the church tower rang out the time—eleven-thirty by the clock. Burbage was well aware of the hour before it was announced. His stomach had told him it was time to take dinner. So late, he thought. And the sets still needed repairs. With Whitman’s funeral and so little time to prepare, the production would be a disaster! The troupe could no longer afford to play half-empty galleries. Not with the new batch of costumes recently purchased—genuine furs for the king’s robes. Such extravagance his brother, Richard, insisted upon. And the new swords! Not to mention the two new hired men and another member demanding to be a sharer.

Then there was the constant threat of Black Death. The outbreaks of plague had subsided long enough to allow the Master of the Revels to reopen the theaters. But if this year’s epidemic proved to be as deadly as last year’s, the theater doors again would be locked. Gods, would that be calamitous financially!

Shakespeare caught up with him and the two of them began their journey back to Southwark just across London Bridge.

“You seem lost in thought, friend,” Shakespeare said.

“The business of providing pleasure to others,” Cuthbert answered. “No matter. How’d you fare with the widow?”

Shakespeare looked impish. “Margaret will be well provided for.”

“Good,” sighed Cuthbert. “The lady always did prefer you to me.”

“My waifish eyes, dear cousin. They tug at the heartstrings.”

“Or leer at the chest,” mumbled Cuthbert. “Depending on your mood.”

“She refused my crowns, my friend—no surprise, eh? But did agree to take them should there be a time of need.”

“Fair enough.”

Shakespeare stopped walking, “Cuthbert, who would do this to Harry? Yes, someone might filch Harry’s purse as he lay sleeping off one of his drunken states. That has happened before. But murder him? He had not a true enemy this side of the channel.”

“Vagabonds knew nothing of his kindness.”

“True—if his murderer was a highwayman …”

“And you think it might be someone else? Someone he knew?”

“I’ve no pull to one theory or the other.”

Cuthbert said, “There is the possibility that Harry became drunk and a foolish fight ensued after words were spoken in choler. Harry often spoke carelessly when drunk.”

“Yet he was equally quick with the apologies,” Shakespeare said. “Besides, he died in an open field and not on the floor of a tavern.”

Alone, Shakespeare thought.

“He could have been moved to the field,” Cuthbert said.

“A lot of bother,” Shakespeare said.

Cuthbert agreed. He asked,

“What about the coins he was carrying? Margaret made mention that Harry had pocketed several angels before he left for his trip up North. They were gone when the body was discovered. Harry was robbed, Willy.”

“Or Harry spent the money before he was murdered,” Shakespeare said.

Cuthbert conceded the point. They resumed walking. It seemed to Shakespeare that Harry could have easily done in an ordinary highwayman itching for a scrap. Whitman was a deft swordsman. But was he caught off guard? Had the attacker been a fiercesome enemy or a madman possessed by an evil spirit? Shakespeare stepped in silence for several minutes, brooding over the fate of his partner and friend. Again Cuthbert placed a hand on his shoulder. He said, softly,

“What’s the sense, Will? Harry is dead and gone. But we are still among the living. We’ve a performance at two and our stomachs are empty.”

“I’ve not an appetite,” Shakespeare said. “But a pint of ale would well wet my throat.”

Cuthbert coughed.

“And yours, also,” added Shakespeare. “Have you seen an apothecary about the cough?”

“Aye.”

“And what did he say?”

“Quarter teaspoon dragon water, quarter teaspoon mithridate, followed by a quart of flat warmed ale. If it worsens, perhaps more drastic measures need to be taken.”

“What kind of measures?”

“He made mention of leeching.”

They were silent for a moment.