По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

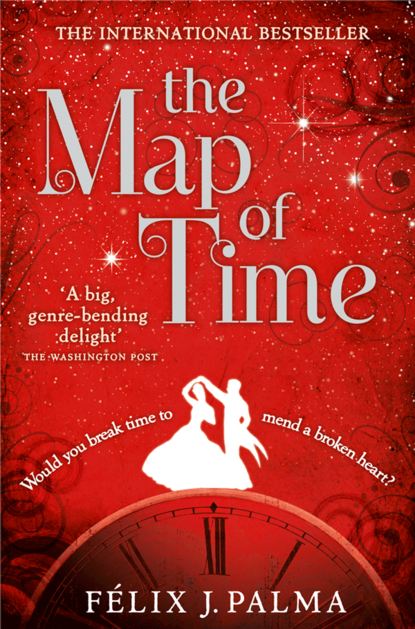

The Map of Time

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Hm, it’s just a suspicion … but when our company first started, there was someone who vehemently opposed it. He insisted time travel was too dangerous, that it had to be taken slowly. I always suspected he said this because he had a time machine, and wanted to experiment with it before making it public. Or perhaps he wanted to keep it to himself, to become the only master of time.’

‘Who are you talking about?’ asked Andrew.

Murray sat back in his chair, a smug grin on his face. ‘Why, Mr Wells, of course,’ he replied.

‘But, whatever gave you that idea?’ asked Charles. ‘In his novel Wells only writes about journeying into the future. He doesn’t even envisage the possibility of going back in time.’

‘That’s exactly my point, Mr Winslow. Just imagine, gentlemen, if somebody were to build a time machine, the most important invention in the history of humanity. Given its incredible potential, they would have no choice but to keep it secret, to prevent it falling into the hands of some unscrupulous individual who might use it for their own ends. But would they be able to resist the temptation to divulge their secret to the world? A novel would be the perfect way of making their invention known without anyone ever suspecting it was anything but pure fiction. Don’t you agree? Or if vanity doesn’t convince you as a motive, then what if they weren’t trying to satisfy their ego at all? What if The Time Machine were merely a decoy, a message in a bottle cast into the sea, a cry for help to somebody who might know how to interpret it? Who knows? Anyway, gentlemen, Wells did contemplate the possibility of going back in time, and with the aim of changing it, moreover, which I imagine is what motivates you, Mr Harrington.’

Andrew jumped, as if he had been discovered committing a crime. Murray smiled at him wryly, then rifled through one of his desk drawers. He pulled out a copy of Science Schools Journal dating from 1888 and threw it on to the table. The title on the cover of the dog-eared periodical was The Chronic Argonauts, by H. G. Wells. He handed it to Andrew, asking him to take good care of it as it was a rare copy.

‘Exactly eight years ago, as a young man having recently arrived in London and ready to conquer the world, Wells published a serial novel entitled The Chronic Argonauts. The main character was a scientist called Moses Nebogipfel, who travelled back in time to commit a murder. Perhaps Wells considered he had overreached himself, and when he recycled the idea for his novel, he eliminated the journeys into the past, perhaps so as not to give his readers ideas. In any case, he decided to concentrate solely on travelling into the future. He made his protagonist a far more upright character than Nebogipfel, as you know, and never actually mentions his name in the novel. Perhaps Wells could not resist this gesture.’ Andrew and Charles stared at one another, then at Murray, who was scribbling something in a notebook. ‘Here is Wells’s address,’ he said, holding out a scrap of paper to Andrew. ‘You have nothing to lose by seeing whether my suspicions are well founded or not.’

Chapter X

Drifting through the scent of roses suffusing the lobby, the cousins left the offices of Murray’s Time Travel. In the street, they hailed the first hansom cab they saw and gave the driver the address in Woking, Surrey, where the author H. G. Wells lived. The meeting with Gilliam Murray had plunged Andrew into a profound silence where God only knew what dark thoughts he was grappling with. But the journey would take at least three hours, and therefore Charles was in no hurry to draw his cousin into conversation. He preferred to leave him to gather his thoughts. They had experienced enough excitement for one day, and there was still more to come. In any case, he had learned to sit back and enjoy the frequent unexpected bouts of silence that punctuated his relationship with Andrew, so he closed his eyes and let himself be rocked by the cab as it sped out of the city.

Although they were not troubled by the silence, I imagine that you, who are in a sense sharing their journey, might find it a little tiresome. Therefore, rather than lecture you on the nature and quality of this inviolate calm, scarcely broken by the cab’s creaks and groans, or describe to you the view of the horses’ hindquarters upon which Andrew’s gaze was firmly fixed, and, since I am unable even to relate in any exciting way what was going on in Andrew’s head (where the prospect of saving Marie Kelly was slowly fading because, although a method of travelling through time had apparently been discovered, it was still impossible to do so with any accuracy), I propose to make use of this lull in proceedings to tell you about something still pending in this story. I alone can narrate this, as it is an episode about which the cab’s occupants are completely unaware.

I refer to the spectacular ascent up the social ladder of their respective fathers, William Harrington and Sydney Winslow. William Harrington presided over it, with his typical mixture of good fortune and rough-and-ready abilities, and although both men resolved to keep it secret, they cannot do so from me, as I see everything whether I wish to or not.

I could give you my honest opinion of William Harrington, but what I think is of no consequence. Let us rather stick with Andrew’s idea of his father, which is not far from the truth. Andrew saw his father as a warrior of commerce, capable, as you will discover, of the most heroic exploits in the field of business. However, when it came to everyday hand-to-hand combat, in which the struggles that make us human take place, allowing us to show kindness or generosity, he was apparently incapable of anything but the meanest acts, as you have already seen. William Harrington was of the class of person who possesses a self-assurance that is both their strength and their downfall, a cast-iron confidence that can easily turn into excessive, blind arrogance. In the end, he was like someone who stands on his head, then complains that the world is upside down, or, if you prefer, like someone who believes God created the Earth for him to walk upon, with which I have said enough.

William Harrington returned from the Crimea to a world dominated by machines. He realised straight away that this would not supersede the old way of doing things since even the glass in the Crystal Palace, that transparent whale then marooned in Hyde Park, had been made by hand. That was evidently not the way to grow rich, a goal he had set himself, with the typical insouciance of a twenty-year-old, as he lay in bed at night with his new wife, the rather timid daughter of the match manufacturer for whom he worked. The thought of being trapped in the dreary life already mapped out for him kept him awake, and he wondered whether he ought not to rebel against such a common fate. Why had his mother gone to the trouble of bringing him into the world if the most exciting moment in his life was having been lamed by a bayonet? Was he doomed to be just another anonymous cipher, or would he pass into the annals of history?

His lamentable performance in the Crimea would appear to suggest the former, yet William Harrington had too voracious a nature to be content with that. ‘As far as I can tell, I only have one life,’ he said to himself, ‘and what I don’t achieve in this one I won’t achieve in the next.’

The following day he called on his brother-in-law Sydney, a bright, capable young man who was wasting his life as an accountant in the family match firm, and assured him that he, too, was destined for greater things. However, in order to achieve the rapid social ascent William envisaged, they must forget the match business and start up their own enterprise, easily done if they made use of Sydney’s savings. During the course of a long drinking session, William convinced his brother-in-law to let him play with his money, declaring that a small amount of entrepreneurial risk would inject some excitement into his dull life. They had little to lose and much to gain. It was essential they find a business that would bring in large profits quickly, he concluded.

To his amazement, Sydney agreed, and soon put his imaginative mind to work. He arrived at their next meeting with the plans for what he was convinced would be a revolutionary invention. The Bachelor’s Helpmate, as he had called it, consisted of a chair designed for lovers of erotic literature, and was equipped with a lectern that automatically turned the pages, allowing the reader to keep both hands free. William could see from Sydney’s detailed drawings that the device came with accessories, such as a small washbasin, and even a sponge, so that the client did not have to interrupt his reading to get up from the chair. Sydney was convinced his product would make their fortune, but William was not so sure: his brother-in-law had clearly confused his own necessities with those of others. However, once William had succeeded in the difficult task of convincing him that his sophisticated seat was not as essential to the Empire as he had imagined, they found themselves without a decent idea to their names.

Desperate, they concentrated on the flow of merchandise coming in from the colonies. What products had not yet been imported? What unfulfilled needs did the British have? They looked around carefully, but it seemed nothing was wanting. Her Majesty, with her tentacular grasp, was already divesting the world of everything her subjects required. Of course, there was one thing they lacked, but this was a necessity no one dared to mention.

They discovered it one day while strolling through the commercial district of New York, where they had gone in search of inspiration. They were preparing to return to the hotel and soak their aching feet in a basin of salt water, when their eye fell on a product displayed in a shop window. Behind the glass was a stack of strange packets containing fifty sheets of moisturised paper. Printed on the back were the words ‘Gayetty’s Medicated Paper’. What the devil was this for? They soon discovered the answer from the instructions pasted in the window, which, without a hint of embarrassment, depicted a hand applying the product to the most intimate area of a posterior. This fellow Gayetty had obviously decided that corncobs and parish newsletters were a thing of the past.

Once they had recovered from their surprise, William and Sydney looked at each other meaningfully. This was it! It did not take a genius to imagine the warm reception thousands of British backsides, raw from being rubbed with rough newspaper, would give this heaven-sent gift. At fifty cents a packet, they would soon make their fortune. They purchased enough stock to furnish a small shop they acquired in one of London’s busiest streets, filled the window with their product, put up a poster illustrating its correct usage, and waited behind the counter for customers to flock in. But not a single soul walked through the door on the day the shop opened, or in the days that followed, which soon turned into weeks.

It took William and Sydney three months to admit defeat. Their dreams of wealth had been cruelly dashed at the outset, although they had enough medicated paper never to need worry about procuring another Sears catalogue. However, at times society obeys its own twisted logic, and the moment they closed their disastrous shop, their business suddenly took off. In the dark corners of inns, in alleyway entrances, in their own homes during the early hours, William and Sydney were assailed by a variety of individuals who, in hushed tones and glancing furtively about them, ordered packets of their miraculous paper before disappearing back into the gloom.

Surprised at first by the cloak-and-dagger aspect they were obliged to adopt, the two young entrepreneurs soon became accustomed to tramping the streets at dead of night, one limping along, the other puffing and panting, to make their clandestine deliveries far from prying eyes. They soon grew used to depositing their embarrassing product in house doorways, or signalling with a tap of their cane on window-panes, or tossing packets off bridges on to barges passing noiselessly below, slipping into deserted parks and retrieving wads of pound notes stashed under a bench, whistling like a couple of songbirds through mansion railings. Everyone in London wanted to use Gayetty’s wonderful paper without their neighbour finding out, a fact of which William slyly took advantage, increasing the price of his product to what would eventually become an outrageous sum – which most customers were nevertheless willing to pay.

Within a couple of years they were able to purchase two luxurious dwellings in the Brompton Road area, from where they soon upped sticks for Kensington. In addition to his collection of expensive canes, William measured his success by the ability to acquire ever larger houses.

Amazed that the reckless act of placing his entire savings at his brother-in-law’s disposal had provided him with a fine mansion in Queen’s Gate from whose balcony he could survey the most elegant side of London, Sydney resolved to enjoy what he had, giving himself to the pleasures of family life, so extolled by the clergy. He filled his house with children, books, paintings by promising artists, took on a couple of servants and, at a safe distance from them now, cultivated the disdain he claimed he had always felt towards the lower classes to the extent that it became contempt. In brief, he quietly adapted to his new affluence even though it was based on the ignoble business of selling toilet paper.

William was different. His proud, inquisitive nature made it impossible for him to be satisfied with that. He needed public recognition, to be respected by society. In other words, he wanted the great and the good of London to invite him foxhunting, to treat him as an equal. But, much as he paraded through London’s smoking rooms doling out his card, this did not happen. Faced with a situation he was powerless to change, he built up a bitter resentment of the wealthy élite, who subjected him to the most abysmal ostracism while wiping their distinguished backsides with the paper he provided. During one of the rare gatherings to which the two men were invited, his anger boiled over when some wag bestowed on them the title ‘Official Wipers to the Queen’. Before anyone could laugh, William Harrington hurled himself on the insolent dandy, breaking his nose with the pommel of his cane before Sydney managed to drag him away.

The gathering proved a turning point in their lives. William Harrington learned from it a harsh but valuable lesson: the medicinal paper to which he owed everything, and which had generated so much wealth, was a disgrace that would stain his life for ever unless he did something about it. He began to invest part of his earnings in less disreputable businesses, such as the burgeoning railway industry. In a matter of months he had become the majority shareholder in several locomotive repair shops. His next step was to buy a failing shipping company called Fellowship, inject new blood into it, and turn it into the most profitable of ocean-going concerns. Through his tiny empire of successful businesses, which Sydney managed with the easy elegance of an orchestra conductor, in less than two years William had dissociated his name from medicinal paper, cancelling the final shipment and leaving London plunged in silent despair.

In the spring of 1872, Annesley Hall invited him to his first hunt gathering on his Newstead estate, which was attended by all of London society, who eagerly applauded William’s extraordinary achievements. It was there that the witty young man who had made a joke at his expense regrettably perished. According to the newspaper account, the ill-fated youth accidentally shot himself in the foot.

It was around that time when William Harrington dusted off his old uniform and commissioned a portrait of himself bursting out of it, smiling as though his unadorned chest were plastered with medals, and greeting all who entered his mansion with the masterful gaze of sole owner of that corner opposite Hyde Park.

This, and no other, was the secret their fathers so jealously guarded and whose air of light entertainment I considered appropriate for this rather wearisome journey. But I am afraid we have reached the end of our story too soon. Total silence still reigns in the cab and is likely to do so for some time because, when he is in the mood, Andrew is capable of daydreaming for hours, unless prodded with a red-hot poker or doused in boiling oil – neither of which Charles is in the habit of carrying around with him. Therefore I have no other choice but to take flight again so that we reach their destination, Mr Wells’s house, more quickly than they do. Not only, as you will have gathered from some of my commentaries, am I not subject to the cab’s tortuous pace but I can travel at the speed of light, so that – voilà! - in the blink of an eye, or faster still, we find ourselves in Woking, floating above the roof of a modest three-storey house with a garden overrun by brambles and silver birch, whose frail façade trembles slightly as the trains to Lynton roar past.

Chapter XI

I immediately discover I have picked an inopportune moment to intrude upon Herbert George Wells’s life. In order to inconvenience him as little as possible, I could quickly pass over the description of his physical appearance by saying no more than that the celebrated author was a pale, skinny young man who had seen better days. However, of all the characters swimming like fish in this story, Wells is the one who appears most frequently, no doubt to his regret, which compels me to be a little more precise in my depiction of him.

Besides being painfully thin, with a deathly pallor, Wells sported a fashionable moustache, straight with downward-pointed ends that seemed too big and bushy for his childish face. It hung like a dark cloud over an exquisite, rather feminine mouth, which, with his blue eyes, would have lent him an almost angelic air were it not for the roguish smile playing on his lips. In brief, Wells looked like a porcelain doll with twinkling eyes, behind which roamed a lively, penetrating intellect. For lovers of detail, or those lacking in imagination, I shall go on to say that he weighed little more than eight stone, wore a size eight and a half shoe and his hair neatly parted on the left. That day he smelt slightly of stale sweat – his body odour was usually pleasant – as some hours earlier he had been for a ride with his new wife through the surrounding Surrey roads astride their tandem bicycle, the latest invention that had won the couple over because it needed no food or shelter and never strayed from where you left it. There is little more I can add, short of dissecting the man or going into intimate details such as the modest proportions and slight south-easterly curvature of his manhood.

At that very moment, he was seated at the kitchen table, where he usually did his writing, a magazine in his hands. His stiff body, bolt upright in his chair, betrayed his inner turmoil. For while it might have seemed as though Wells were simply letting himself be enveloped by the rippling shadows cast by the afternoon sun shining on the tree in the garden; he was in fact trying to contain his simmering rage. He took a deep breath, then another and another, in a desperate effort to summon a soothing calm. Evidently this did not work, for he ended up hurling the magazine against the kitchen door. It fluttered through the air like a wounded pigeon and landed a yard or two from his feet.

Wells gazed at it with slight regret, then sighed and stood up to retrieve it, scolding himself for this outburst of rage unworthy of a civilised person. He put the magazine back on the table and sat in front of it again, with the resigned expression of one who knows that accepting reversals of fortune with good grace is a sign of courage and intelligence.

The magazine in question was an edition of the Speaker, which had published a devastating review of his most recent novel, The Island of Doctor Moreau, another popular work of science fiction. Beneath the surface lurked one of his pet themes: the visionary destroyed by his own dreams. The protagonist is a man called Prendick, who is shipwrecked and has the misfortune to be washed up on an uncharted island that turns out to be the domain of a mad scientist exiled from England because of his brutal experiments on animals. On that remote island, the eponymous doctor has become like a primitive god to a tribe made up of the freakish creations of his unhinged imagination, the monstrous spawn of his efforts to turn wild animals into men.

The work was Wells’s attempt to go one step further than Darwin by having his deranged doctor attempt to modify life by speeding up the naturally slow process of evolution. It was also a tribute to Jonathan Swift, his favourite author: the scene in which Prendick returns to England to tell the world about the phantasmagorical Eden he has escaped from is almost identical to the chapter in which Gulliver describes the land of the Houyhnhnm. And although Wells had not been satisfied with his book, which had evolved almost in fits and starts from the rather haphazard juxtaposition of more or less powerful images, and had been prepared for a possible slating by the critics, it stung all the same.

The first blow had taken him by surprise, as it had come from his wife, who considered the killing of the doctor by a deformed puma he had tried to transform into a woman a jibe at the women’s movement. How could Jane possibly have thought that? The next jab came from the Saturday Review, a journal he had hitherto found favourable in its judgements. To his further annoyance, the objectionable article was written by Peter Chalmers Mitchell, a young, talented zoologist who had been Wells’s fellow pupil at the Normal School of Science, and who, betraying their once friendly relations, now declared bluntly that Wells’s intention was simply to shock. The critic in the Speaker went still further, accusing the author of being morally corrupt for insinuating that anyone succeeding through experimentation in giving animals a human appearance would logically go on to engage in sexual relations with them. ‘Mr Wells uses his undoubted talent to shameless effect,’ declared the reviewer. Wells asked himself whether his or the critic’s mind was polluted by immoral thoughts.

Wells was only too aware that unfavourable reviews, while tiresome and bad for morale, were like storms in a teacup that would scarcely affect the book’s fortunes. The one before him now, glibly referring to his novel as a depraved fantasy, might even boost sales, smoothing the way for his subsequent books. However, the wounds inflicted on an author’s self-esteem could have fatal consequences in the long-term: a writer’s most powerful weapon, his true strength, was his intuition and, regardless of whether he had any talent, if the critics combined to discredit it, he would be reduced to a fearful creature who took a mistakenly guarded approach to his work that would eventually stifle his latent genius. Before cruelly vilifying them, mud slingers at newspapers and journals should bear in mind that all artistic endeavours were a mixture of effort and imagination, the embodiment of a solitary endeavour, of a sometimes long-nurtured dream, when they were not a desperate bid to give life meaning.

But they would not get the better of Wells. Certainly not. They would not confound him, for he had the basket.

He contemplated the wicker basket sitting on one of the kitchen shelves, and his spirits lifted, rebellious and defiant. The basket’s effect on him was instantaneous. As a result, he was never parted from it, lugging it around from pillar to post, despite the suspicions this aroused in his nearest and dearest. Wells had never believed in lucky charms or magical objects, but the curious way in which it had come into his life, and the string of positive events that had occurred since then, compelled him to make an exception in the case of the basket. He noticed that Jane had filled it with vegetables. Far from irritating him, this amused him. In allocating it that dull domestic function, his wife had at once disguised its magical nature and rendered it doubly useful: not only did the basket bring good fortune and boost his self-confidence, not only did it embody the spirit of personal triumph by evoking the extraordinary person who had made it, it was also just a basket.

Calmer now, Wells closed the magazine. He would not allow anyone to put down his achievements, of which he had reason to feel proud. He was thirty years old and, after a long, painful period of battling against the elements, his life had taken shape. The sword had been tempered and, of all the forms it might have taken, had acquired the appearance it would have for life. All that was needed now was to keep it honed, to learn how to wield it and, if necessary, allow it to taste blood occasionally. Of all the things he could have been, it seemed clear he would be a writer – he was one already. His three published novels testified to this. A writer. It had a pleasant ring to it. And it was an occupation that he was not averse to: since childhood it had been his second choice, after that of becoming a teacher – he had always wanted to stand on a podium and stir people’s consciences, but he could do that from a shop window, and perhaps in a simpler and more far-reaching way.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: