По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

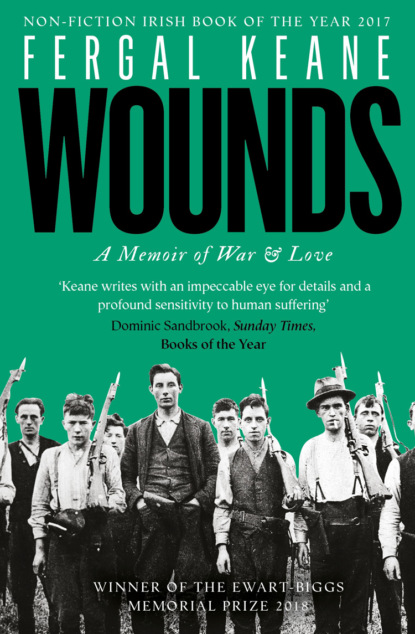

Wounds: A Memoir of War and Love

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

In January 1833 the Morning Chronicle recorded that a bailiff working for the Reverend Anthony Stoughton and his brother Colonel Stoughton of Listowel was murdered by being ‘struck on the back of the head with a stone and received about twenty bayonet wounds’.22 (#litres_trial_promo) On another occasion a horse belonging to the brothers was cut in two. The so called ‘Tithe War’ witnessed a familiar ritual of midnight raids but also the politics of highly organised intimidation, not just aimed at the clergy but against those who agreed to pay their tithes. State retribution was harsh, with instances of troops shooting on protesting crowds. But the conflict marked the beginning of the end of the Church of Ireland as the established church and in 1838 the government acted to transfer responsibility for the upkeep of Anglican clerics to the landlords.* (#ulink_a36dd26b-1c9b-504f-b409-02b930308e0c)

Poverty is not a necessary precondition for civil strife, but mix it with memories of dispossession, in a system based on the supremacy of a minority, and the emergence of groups such as the Whiteboys, and others in years to come, seems utterly logical. They were men and women with nothing to lose and the raw courage of youth. They did not fight for a nation state, or the republican ideals of Wolfe Tone and the United Irishmen. They fought for the ground beneath their feet.

* (#ulink_3b2acfc6-57c2-5fba-9a34-ed7b1e3bfb85) The final phase in the decline of Church of Ireland power came with the Irish Church Act of 1869 which did away with the payment of tithes and replaced them with a life annuity.

3

My Dark Fathers (#ulink_bfb58a22-a978-5fcc-a4b8-9a5e07450977)

My Dark Fathers lived the intolerable day

Committed always to the night of wrong,

Stiffened at the hearthstone, the woman lay,

Perished feet nailed to her man’s breastbone.

Grim houses beckoned in the swelling gloom

Of Munster fields where the Atlantic night

Fettered the child within the pit of doom,

And everywhere a going down of light.

Brendan Kennelly, ‘My Dark Fathers’, 19621 (#litres_trial_promo)

I

The Earl was well pleased with his welcome. The gentry had assembled, as had the local clergy, including the formidable Father Jeremiah Mahony, parish priest of St Mary’s, who delivered a vote of thanks to his Protestant counterpart, Reverend Edward Denny, ‘for his dignified conduct on this, and every other occasion, when called on’.2 (#litres_trial_promo) The occasion was a welcome party for the new Earl of Listowel, William Hare, and the language was indicative of something more than the ritual flattery reserved for visits of the mighty. The priest had reason to welcome the Earl, who had been a supporter of Catholic emancipation and provided land for the new Catholic church on the square directly opposite the Protestant St John’s. His liberalism on religion put him at odds with several powerful fellow landowners in the area. The formal address urged the Earl to make his visits ‘frequent and prolonged’ and sought his ‘protection and tutelage’ for ‘a grateful tenantry’.3 (#litres_trial_promo) At that moment, seated behind the ivy-clad walls of the Listowel Arms Hotel, among the smiles and handshakes of the men of property, within yards of the Protestant church and its new, taller-spired Catholic counterpart, the Earl might have hoped for a tranquil residence. But beyond the Feale bridge on either side of the road towards Limerick, by the Tarbert road and the road to Ballydonoghue, in every field in north Kerry where potatoes were planted, a catastrophe was taking root.

They were used to hunger. Seven Irish famines of varying extremes had struck since the middle of the eighteenth century. Outside the rapidly industrialising north-east the country was mired in poverty with average income half that of the rest of the United Kingdom. The rural population had grown rapidly, encouraged by the nourishment provided by the widespread cultivation of the potato, and the growing trend to marry young. In the twenty years before the Famine the number of people subsisting in the area increased by nearly two thousand souls.

By the summer of 1839, two years after the new Lord Listowel was welcomed to the town, there were warnings of crisis. At a public meeting in Listowel, the gentry and the clergy (Protestant and Catholic) and prominent townspeople heard reports of the ‘increasing difficulties of the labouring classes of this district from the enormous prices which the commonest provisions have reached; agricultural labour, about the only source of employment, has now already terminated’.4 (#litres_trial_promo) The meeting noted ominously that the potato crop of the previous harvest had failed. Public works schemes to alleviate the distress of the poor were already under way and 4,000 people each day received rations of oatmeal. The novelist William Makepeace Thackeray passed through Listowel in the same year and saw a town that ‘lies very prettily on a river … [but] it has, on a more intimate acquaintance, by no means the prosperous appearance which a first glance gives it’.5 (#litres_trial_promo)

The writer, at best a condescending witness to Irish travails, went on to record the poverty of the scene, the numerous beggars (their number undoubtedly swollen by the growing hunger in the countryside), the appearance of ‘the usual crowd of idlers round the car: the epileptic idiot holding piteously out his empty tin snuff-box; the brutal idiot, in an old soldier’s coat, proffering his money-box and grinning and clattering the single halfpenny it contained; the old man with no eyelids, calling upon you in the name of the Lord; the woman with a child at her hideous, wrinkled breast; the children without number’.6 (#litres_trial_promo) The following year the Kerry Evening Post recorded the failure of the potato crop in the north of the county. A landowner near Ballydonoghue noted in his journal: ‘we were concerned to hear many complain of a dry rot appearing more extensively than hitherto … The farmers are very apprehensive of it.’7 (#litres_trial_promo) In early February the first of the destitute were admitted to the workhouse in Listowel.

The Purtills and their neighbours watched as a vast withering engulfed the fields of north Kerry in the late summer of 1845. The land agent, William Trench, gave a vivid account of his first encounter with the blight:

The leaves of the potatoes on many fields I passed were quite withered, and a strange stench, such as I had never smelt before, but which became a well-known feature in ‘the blight’ for years after, filled the atmosphere adjoining each field of potatoes. The crop of all crops, on which they depended for food, had suddenly melted away, and no adequate arrangements had been made to meet this calamity, the extent of which was so sudden and so terrible that no one had appreciated it in time, and thus thousands perished almost without an effort to save themselves.8 (#litres_trial_promo)

Soon the smell of the rotting crop was thick around Ballydonoghue. It would be followed soon enough by the smell of corpses.

The newspapers of Kerry and Cork provide us with a picture of deepening distress over the Famine years. There was relief, but never enough. Concern by some landlords, but indifference and cruelty from others. In August 1846 the correspondent of the Cork Examiner reported that the potato crop ‘was not partially but totally destroyed in the neighbourhood of Listowel … the common cholera has set in there without a particle of doubt’.9 (#litres_trial_promo) By autumn desperation had given way to rage. In November a crowd of up to six thousand came to Listowel ‘shouting out “Bread or Blood” and proceeded in the greatest state of excitement to attack the Workhouse … with the intention of forcibly helping themselves to whatever provisions they might find within the building.’10 (#litres_trial_promo) They were stopped by the intervention of a popular priest.

North Kerry was devastated. The Tralee Evening News of 16 February 1847 described how: ‘Fever and dysentery prevail here to a frightening extent.’ The ‘bloody flux’ reduced its victims to hopelessly defecating shadows who squatted and lurched in roads, lanes, fields, market squares, on the seashore and riverside, reduced by the mayhem of disease, covered in their own waste, uncared for, and, when they died, often left unburied. ‘Men women and children [are] thrown into the graves without a coffin,’ reported the Kerry Examiner, ‘no inquests inquire as to how they came by their death, as hunger has hardened the hearts of the people. Those who survive cannot long remain so – the naked wife and children staring them in the face – their bones penetrating through the skin.’11 (#litres_trial_promo)

A parish historian recorded the deaths of eighty people in 1847, nearly half of whom were buried without coffins.* (#ulink_cf0d13a1-e851-5f97-8b44-1aaedb1213ff) Kerry had the second-highest rate of recorded deaths from dysentery during the Famine. Starvation and disease would take the lives of around 18,000 people in just a single decade.

Rural labourer in Famine era (Sean Sexton Collection)

Thousands fled, emigrating to Britain and further afield. Taking ship to escape poverty was an established feature of life in the area and the expanding frontiers of North America offered opportunity. Garret and Mary Galvin from Listowel arrived in Canada with only meagre belongings but within a few years were farming thirty-six acres in Ontario, with twelve cattle, two horses, seventeen pigs and forty sheep. That was in 1826. Two decades later conditions were unrecognisably worse: the government logs of passengers do not even list their names. A few entries picked from the records of the year 1851, hint at the great migration:

18 July: twenty-eight from Listowel make the crossing to Quebec on the ship Jeannie Johnstone.

29 August: sixty-five from Listowel board for Canada on the ship Clio.

26 September: thirteen from Listowel sail on the John Francis …12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Passengers were often selected by their landlords, being of no further economic use on the land, or by the guardians of the workhouses, and sent away to North America with just the price of their fare.

At Quebec the immigrants disembarked at Grosse Isle in the St Lawrence archipelago. Five thousand were buried there, the majority killed by typhus. A priest who went on board the arriving ships left an account of desolation:

Two to three hundred sick might be found in one ship, attacked by typhoid fever and dysentery, most lying on the refuse that had accumulated under them during the voyage; beside the sick and the dying were spread out the corpses that had not yet been buried at sea. On the decks a layer of muck had formed so thick that footprints were noticeable in it. To all this add the bad quality of the water, the scarcity of food and you will conceive but feebly of the sufferings that people endured during the long and hard trip. Sickness and death made terrible inroads on them. On some ships almost a third of the passengers died. The crew members themselves were often in such bad shape that they could hardly man the ship.13 (#litres_trial_promo)

A report from the government in Quebec noted that those ‘sent out by their landlords were chiefly large helpless families, and in many instances widows and their children’ and that they ‘were generally very scantily supplied … The condition of many of the emigrants, I need not inform you, was deplorable.’14 (#litres_trial_promo) A priest gave the last rites to the dying. ‘I have not taken off my surplice today,’ wrote Father Bernard McGauran, ‘they are dying on the rocks and on the beach, where they have been cast by the sailors who simply could not carry them to the hospitals. We buried 28 yesterday, 28 today, and now (two hours past midnight) there are 30 dead whom we will bury tomorrow. I have not gone to bed for five nights.’15 (#litres_trial_promo)

The Listowel passengers on the ship Clio were told to expect a sum of money from the Listowel Union on arrival. Nothing was sent and they were left ‘entirely without means’. The colonial government moved them on to where they might find work.

In the same period Scots Highlanders were also being shipped out by their landlords. A Colonel Gordon sent his entire tenantry – 1,400 people from the islands of Barra and Uist – to Canada. But to those Irish who were forced into migration, and to those left behind, what mattered was their particular circumstance. Even if they had been aware of the sufferings inflicted on the Scottish and English poor it would not have ameliorated their sense of loss, or the accumulation of grievance that the Famine caused. Nor would it have disposed them to think more highly of the government and the landlords. The wider context is everything until it is nothing at all.

My grandmother Hannah and her brother Mick and their friends were brought up with stories of the Famine as passed on by their grandparents. Moss Keane from Ballygrennan outside Listowel recalled his grandfather’s memories: ‘The families used to get sick and die. The fever was so bad in the end they used to bury the people by throwing their mud houses down on them; then they were buried. The English could relieve them if they wished … Many a person was found dead on the roadside with grass on their mouths.’16 (#litres_trial_promo) As always the spirit world was invoked in memory of the dead. People told of meeting them along the road.

They were in the ground but walking still.

One story relates how a prosperous landowner came to gloat at a starving old woman. She was so ashamed of her plight that she boiled stones in the pot and pretended they were potatoes. ‘But when the time came, she found flowery bursting spuds in the pot.’17 (#litres_trial_promo) Another tells of a great fiddler from the locality who was buried in a mass grave and whose music could still be heard on certain nights. I found out that there had indeed been such a man, a famous dancing master who died of exposure in Listowel Workhouse.* (#ulink_615082d1-3f4c-5955-978f-8ccfd89fc1d6)

I met a woman walking past Ballydonoghue church one evening who turned out to be a family friend of the Purtills. Nora Mulvihill was born and reared here and came from a line that went back to the nineteenth century. Nora was middle-aged with grown-up children, and most evenings she walked the local roads to keep fit. Drive the roads of rural Ireland any evening and weather and you will see women like her, heads down and arms swinging. She knew the land and its stories.

We drove to Gale cemetery where the dead of the Famine from Ballydonoghue were buried. ‘Do you know about the doctors that were here?’ she asked. I assumed she meant the medics who visited the workhouse during the disease epidemics. But no, Nora had another story. I would leave without knowing how to interpret what I was told. Maybe it was just a story, like so many of the others told over the generations by the old people, a story with some truth maybe or none, or maybe entirely true. But it was a story that lasted. ‘There was a house above in Coolard where there were doctors,’ Nora told me. ‘I don’t know who they were or what they were doing there, whether it was the one family or whatever. But at any rate they lived there through the hunger. At the time there was a lot of dead bodies lying around the place. People were falling on the roads. So the doctors sent their servants out to bring in bodies to them and they had a room upstairs in the house where they did experiments. When they were finished with them a man would come with a cart and take the corpses to the graveyard here.’ The man was known locally as ‘Jack the Dead’.

A local historian, John D. Pierse, found an account of a ‘Dr Raymond [who] used to buy bodies for a couple of shillings from the local people … he’d come at the diseased part of the body and examine it … they used to do that wholesale.’18 (#litres_trial_promo) The county archives showed that Dr Samuel Raymond was living in this area in 1843, on the eve of the Famine, and was still serving as a magistrate in 1862. It may have been that he was carrying out sample autopsies on behalf of the government. But in the memory of the place he is a ghoulish exploiter to whom the bodies of the dead were mere biological material.

The stories offered the poor a promise that their suffering would be remembered, if not by individual names, then at least the manner of their death, a series of accusing fingers pointing out of the past at the English, the landlords, the big Catholic farmers who had food on their tables every night … at the whole army of their ‘betters’.

The Listowel Workhouse was the repository of the doomed. Those who ended up in this cramped, disease-ridden barracks had lost all hope of survival on the outside. A doctor treating smallpox sufferers found that ‘three or four fever patients are placed in beds that are unusually small’. He witnessed two children die soon after arriving ‘probably being caused by the cold to which such children were exposed to on account of being brought in so long a distance’.19 (#litres_trial_promo) The doctor found the body of a newborn baby in the latrines. A record for the 22 March 1851 documented the deaths of sixty-six people in the workhouse, of whom forty-nine were under the age of fifteen.

Out of this misery grew an ambitious scheme. A report at the height of the Famine quoted the Listowel Workhouse master as saying ‘the education of the female children appears to be very much neglected … very few could even read very imperfectly. Only one or two make any attempt at writing.’20 (#litres_trial_promo) The remedy to illiteracy and the prospect of death from starvation or disease was to pack thirty-seven girls off to Australia. They were among 4,000 Irish girls selected to find new lives in the colonies. Most ended up marrying miners or farmers in the outback. In the great departures that followed the Famine, some of my own Purtill relatives took ship for America, settling in Kentucky and New York, and bringing with them a memory of loss to be handed to the coming generations. Their children would learn that as many as half a million people were evicted from their homes during the Famine; that the government failed the starving when it might, through swifter action, have saved hundreds of thousands; they learnt that the poor were damned by the incompetence of ministers and by their rigid ideological beliefs, the conviction that the market was God; that the poor should learn a lesson about the ‘moral hazard’ of their own fecklessness; that too much charity would weaken the paupers’ determination to help themselves – and that all of this was part of God’s plan. It was not genocide in the manner I have known it. Genocide takes a plan for extermination with a defined course set at the outset. But it was a moral crime of staggering proportions.

The Famine changed the world around the Purtills. But they survived. How? Were they tougher than others? I will never know. There is only one narrative of the Famine when I am growing up. This is of English infamy, the clearances and evictions and the workhouse. But it is not the whole story. The story of survival and its psychological costs is not told: how some of the bigger Catholic farmers also evicted tenants, how the vanishing of the labouring class created the room for bigger farms, and how the Famine set in train the destruction of the landlord system. Hunger begets desperation, begets fierce survival strategies, and these beget shame which begets silence.

I find myself going back to Brendan Kennelly’s ‘My Dark Fathers’. I do so because I believe there are parts of history only the poets can convey, the deeper emotional scars that form themselves into ways of seeing things that inhabit later generations. Brendan told me he had written the poem after attending a wedding in north Kerry. A boy was called upon to sing. He had a beautiful voice but was painfully shy. So he turned to face the wall and in this way was able to perform. Kennelly was transfixed. He saw in that moment the shame of survival that had stalked his ancestors and mine.

Skeletoned in darkness, my dark fathers lay

Unknown, and could not understand

The giant grief that trampled night and day,