По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

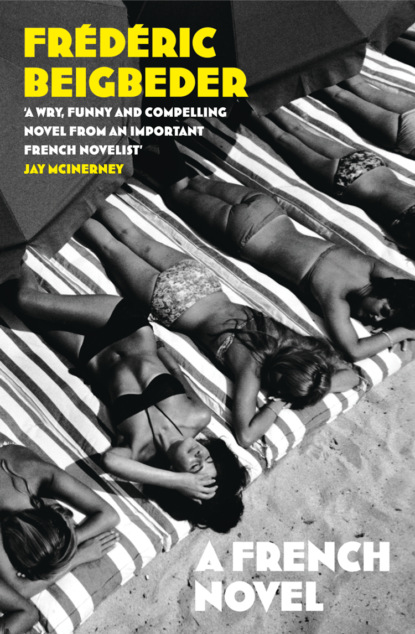

A French Novel

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

in the depths of these eyes that hold no promises,

in the back yards of ramshackle buildings, among lonely dancers and drunken barmen,

between green rubbish bins and silver convertibles,

I looked for you among fractured stars and violet perfumes,

in icy hands and syrupy kisses, at the bottom of rickety staircases,

at the top of brightly lit elevators,

in pallid joys, in seized opportunities, in fierce handshakes,

and in the end I had to stop looking for you

under a starless vault,

on white boats,

in downy necklines and dark hotels,

in mauve mornings and ivory skies, among marshy dawns,

my vanished childhood.

The police wanted to confirm my identity; I did not protest, it was something I too needed to confirm. ‘Who is it that can tell me who I am?’ asks Lear in Shakespeare’s play.

I haven’t slept a wink all night. I don’t know whether the day has dawned: my sky is a crackling white fluorescent tube. I am squeezed into a lightbox. Deprived of space and time, I occupy a container of eternity.

A custody cell is the part of France where maximum pain is concentrated into the minimum square footage.

It is impossible to cling to my youth.

I have to dig deep within myself, like the prisoner Michael Scofield digging a tunnel in Prison Break. To remember in order to go over the wall.

But how can someone take refuge in memories when he has none?

My childhood is not some paradise lost, nor some ancestral trauma. I imagine it more as a slow period of obedience. People have a tendency to idealise their childhood, but a child is first and foremost a bundle that you feed, carry and put to bed. In exchange for bed and board, the bundle conforms on the whole to policies and procedures.

Those who are nostalgic about their childhood are people who miss the time when they were looked after by others.

In the end, a police station is like a day-care centre: they undress you, feed you, keep an eye on you, stop you from leaving. It’s not illogical that my first night in prison should take me back so far.

There are no more adults, only children of all ages. To write a book about my childhood therefore means talking about myself in the present. Peter Pan is amnesiac.

It’s curious that we say someone ‘saved his own skin’ when he runs away. Isn’t it possible to save your skin while staying put?

I can taste salt in my mouth, just as I used to at the beach at Cénitz when I accidentally ended up swallowing seawater.

6

GUÉTHARY, 1972

Of my entire childhood, one single image remains: the beach at Cénitz, near Guéthary; Spain barely visible, sketched along the horizon, a blue mirage suffused with light; this would have been around 1972, before they built the purification plant that stinks, before the restaurant and the car park blocked the path down to the sea. I see the image of a scrawny little boy and an emaciated old man walking side by side along the beach. The grandfather is much more dashing, tanned and handsome than his sickly, pale grandson. The white-haired man skims flat stones on the sea; they skip across the water. The little boy is wearing an orange swimsuit with a seashell embroidered on the terrycloth; his nose is bleeding, a wad of cotton wool pokes out of his right nostril. Count Pierre de Chasteigner de la Rocheposay looks very like the actor Jean-Pierre Aumont. He shouts, ‘Do you know, Frédéric, I’ve seen whales, blue dolphins, even an orca, right here?’

‘What’s an orca?’

‘It’s a big, black killer whale with teeth as sharp as razorblades.’

‘But …’

‘Don’t worry, the monster can’t come close to the shore, he’s too big; here on the beach you’re in no danger.’

To be on the safe side, I decided that day never to set foot in the water again. My grandfather was teaching me to shrimp with a net, and I remember why my elder brother was not with us. At the time, an eminent doctor had told my mother I might have leukaemia. I was on a rest cure, in ‘rehab’, at the age of seven. I had come to the seaside to gather my strength, to breathe in the fresh salt air through a nose clotted with blood. In my grandfather’s house ‘Patrakénéa’ (Basque for ‘The Peculiar House’), in my damp room, a green hot-water bottle would be slipped into my bed; it made a sploshing sound when I moved, and regularly reminded me of its presence by scalding my feet.

The brain twists childhood, to make it better or worse, to make it more interesting than it was. Guéthary 1972 is like a recovered sample of DNA; like the white-coated forensic officer in the 8th arrondissementpolice station who has just swabbed the insides of my cheeks with a wooden spatula to get a mucus sample, I should be capable of recreating everything from this single strand of hair found on the beach. Unfortunately I am not skilled enough: closing my eyes in my squalid little cell, I can reconstruct only the rocks chafing the soles of my feet, the murmur of the Atlantic roaring in the distance alerting us to the rising tide, the slippery sand between our toes, and my pride that my grandfather has made me responsible for holding the bucket of shrimps wriggling in the brine. On the beach, a few old ladies pull on flowery bathing caps. At low tide, the rocks form little swimming pools, in which the shrimp are held prisoner. ‘You see, Frédéric, you have to scrape around inside the fissures. Go ahead, it’s your turn.’ As he held out the shrimping net, my grandfather, with his white hair and pink espadrilles bought from Garcia, taught me the word ‘fissure’; keeping the net close to the jagged edges of the rocks beneath the water, he caught the poor creatures as they jumped backwards into his net. I tried my luck, but caught only a few listless hermit crabs. But it didn’t matter: I was alone with Bon Papa, and I felt as heroic as he. Walking back up from Cénitz beach, he picked blackberries along the roadside. It was miraculous for a little city kid holding his grandfather’s hand, to discover that nature was a sort of giant smorgasbord: the ocean and the trees teemed with gifts, you had only to stoop and pick them up. Until then I had only ever seen food come out of a fridge or a shopping trolley. I felt as if I were in the Garden of Eden, its pathways burgeoning with fruit.

‘One day, we’ll go to the woods at Vaugoubert and pick ceps under the fallen leaves.’

We never did.

The sky was an uncharacteristic blue: for once, the weather was fine in Guéthary, and the houses seemed to get whiter as we watched, like in those ads for Ajax: The White Tornado. But perhaps it was overcast, perhaps I’m trying to arrange things, perhaps I just need the sun to shine upon the one memory I have of my childhood.

7

NATURAL HELLS

When the police descended on us on the avenue Marceau, we were a dozen revellers huddled together, lighting cigarettes around a car whose gleaming bonnet was striped with parallel white lines. We were more like Marcel Carné’s Youthful Sinners than Larry Clark’s junkie Kids. As soon as the siren began to wail, we scattered to the four winds. The officers only managed to net two delinquents, like my grandfather shrimping, delving into the fissures – in this case the entrance to Alma-Marceau métro station, whose shutters were closed at this late hour. While my friend – let’s call him the Poet – was being arrested, I heard him protest, ‘Life is a nightmare!’ The baffled face of the Policeman in front of the Poet will continue to make me smile until my dying day. Two keepers of the peace carried us right up to the bonnet of contention; I remember having enjoyed this exercise in nocturnal levitation. The ensuing dialogue seemed to be perched midway between Poetry and Public Order.

Policeman: ‘What the hell were you thinking, doing something like that on a car?’

Poet: ‘Life is a NIGHTMARE!’

Me: ‘I am descended from a gallant knight who was crucified on the barbed wire of Champagne.’

Policeman: ‘All right, that’s it, take this lot down to Sarij 8.’

Me: ‘What’s Sarij 8?’

Policeman II: ‘The service for reception, research and judicial investigation of the 8th arrondissement.’

Poet: ‘“As human beings advance through life the romance which dazzled the young man, the fabulousss legend which enchanted him as a child, these wither and grow dim of themselvesss …”’

Me (simultaneously brown-nosing and showing off): ‘That’s not his. Surely you must have read Baudelaire’s Artificial Paradises, Captain? You know that artificial paradises exist to help us escape our natural hells?’

Policeman (into his radio): ‘Boss, we’ve got a violation here!’

Policeman II: ‘You’re crazy to do this on a public highway! Why don’t you hide in the bogs like everyone else? That’s provocation, that is!’