По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

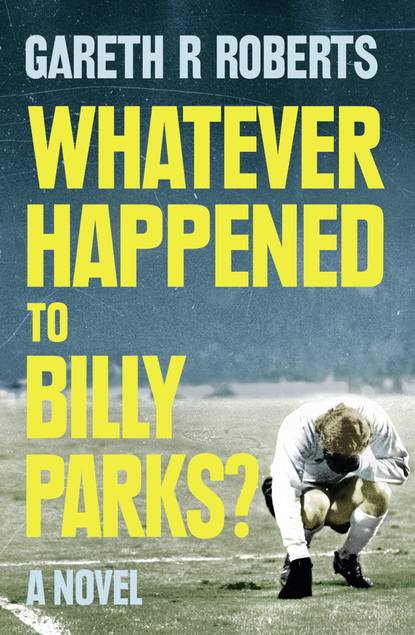

Whatever Happened to Billy Parks

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘You silly, stupid bitch,’ I say, and I’ve gritted my teeth and I’m so, so wrong. And I’ve clenched my fists and for a second I am so angry that I want to punch her, but instead I slam my hand against the empty kitchen table.

Maureen puts her hand up, she’s dealt with much worse than me. ‘Billy,’ she says, ice cold, colder than the North Pole, colder than the surface of Neptune, she sighs, and shakes her head. ‘Just fuck off and kill yourself.’ And with that she’s gone, out the door.

I’m left alone. For about an hour I frantically go through the bins and the cupboards and drawers, looking for a drink. I throw things on the floor and rip out stuff from the back of my wardrobe. I search through boxes crammed with my life history, yellow newspaper clippings, old programmes, photos of me, young and beautiful with my arms around the shoulders of missing friends. I ignore them, I discard them in my search for drink. But there isn’t any. I know there isn’t any. I know that there is no drink in my home. But looking for it has at least made me feel alive.

Alive.

Then tired.

I sit down on my own. I sit down on my bed in my one-bedroom Housing Association flat, panting, and put my head in my hands. Me, Billy Parks, crying like a right twat. I could go out to get more drink. Replace the vodka. I could. I want to. But I can’t do it. Instead I lie on my bed and try to think about something meaningful. I try to picture my daughter and her son. I want to make plans to see them, take the boy somewhere, perhaps I could take him down West Ham, get in the Directors box, see the players, but I can’t make those plans, I can’t form the images in my head, images of happy me and happy daughter and happy boy. It’s too difficult. I can’t even work out how I’ll find her.

I get up and pace around. The dark clouds of self-loathing gather. Then I notice the jigsaw that Maureen’s left on the table, thousands of fucking pieces depicting a detail from the start of the London Marathon – thousands of heads and bodies in running vests with little numbers on them. I sigh. Seventeen hours she said. I sigh again but before I know it I’ve taken the pieces out and I’m turning them over the right way.

I have an idea.

I text Maureen telling her that I’m sorry and that I’m a complete twat, and that I’m starting the jigsaw. Then I telephone Tony Singh, a bookie I know from the pub. ‘Tony,’ I say, ‘Billy Parks here. I’m fine mate, never felt better. Listen, you heard about this jigsaw competition Maureen’s running at the pub? That bloke who works at Lloyds has posted seventeen hours. Yeah. Yeah. What odds you going to give me?’

Fucking four to one: the tight-fisted bastard.

Still – I have two hundred and fifty quid on Billy Parks.

6 (#udf1a4d3f-a94d-5ad4-bdfe-1a7d25e3c762)

Two days later I find Gerry Higgs waiting by the lift at the bottom of my building. He’s got a rather odd, pleased expression across his face. I’m wary, but, I have to admit, intrigued by the old duffer.

‘Hello, Billy,’ he says.

‘Mr Higgs,’ I say, ‘what brings you to these salubrious parts?’

His face breaks out into his most sinister smile. ‘You, of course, Billy,’ he says.

Of course.

‘It’s good news,’ he adds, ‘the Council of Football Immortals have said that you can watch one of their plenary sessions.’

‘Oh,’ I say, ‘that is good news.’ Though in reality I haven’t got the faintest idea what he’s talking about; what the fuck is a plenary session?

‘Actually, I was just off to the bookie’s,’ I tell him and he smiles at me again.

‘Plenty of time for that, old son,’ he says. ‘Come on.’

I follow him like a kitten, and we get into a cab on the High Street.

‘Where are we going?’ I ask him.

‘Lancaster Gate, of course,’ he says.

Of course.

I tell the cab driver. He doesn’t recognise me.

Lancaster Gate, once home of the Football Association. We get out of the cab and I follow Gerry Higgs around to the back of a massive Georgian town house; one of those ones that doesn’t look that big from the outside, but inside is like a fucking Tardis with ballrooms and banqueting suites and all that. We go through a black back door that leads to a well-lit corridor. On the wall are pictures of the greats: Steve Bloomer, the original football superstar, standing upright and handsome with his hair parted like the Dead Sea. Then Dixie Dean, rising to power in a header. Dixie, what a man, bless him, I met him once at a charity do at Goodison Park just before he died. He’d had his legs amputated, the poor bastard; I mean, how cruel is that, taking away the legs and feet of the man who once scored sixty goals in a single season? Then there’s Duncan Edwards, who died in Munich, running on to the pitch all muscle and power knowing that no fucker was going to get the better of him, and Frank Swift, back arched and diving to tip a volley over the crossbar, come to think of it he died in Munich as well, and others, all captured in their prime, beautiful men, athletes, captured before those most horrible devious rotters of all, time and fate, got each and every one of them. Bang, bang, bang, bang.

There are no pictures of me.

At the end of the corridor, Gerry Higgs turns and puts his finger to his lips. ‘Come on,’ he whispers, and he opens a door that leads to a small room with a window in it; through the window I can see another room in which sit a collection of men around three tables that are arranged in a U-shape: I look closer.

Fuck me.

I feel my whole body move towards the men, my eyes wide, bursting out of my skull. I turn to Gerry Higgs, mouth open in wide-eyed-child-like-cor-blimey astonishment.

‘Who are they?’ I ask. But I know.

‘You know who they are,’ says Gerry, grinning like a man who’s just given someone the best Christmas present they’ll ever have and knows it.

‘It can’t be,’ I say and Gerry Higgs just nods at me, the grin remaining on his slobbering lips.

I turn to look at the three tables again. At the top table sits Sir Alf Ramsey. Then at the table to his right is Sir Matt Busby and next to him Bill Shankly, and across from them, scowling at each other are Don Revie and Brian Clough.

‘That’s the Council of Football Immortals, Billy,’ says Gerry Higgs. ‘I told you, didn’t I – the greatest geniuses known to the game of football.’

‘But, Gerry,’ I say, ‘they’re all dead. I mean, I even went to Sir Alf’s funeral.’

Gerry Higgs looks at me like I’m a silly little boy. ‘Billy,’ he says, ‘Billy, Billy, Billy, these men aren’t dead. Men like this never die, they live on and on, way beyond the lifespan of mere mortals. That’s why they’re legends, old son. Proper legends. Not the five-minute wonders you get today.’

I stutter: ‘Gerry, I don’t understand.’ And Gerry Higgs looks at me: ‘Don’t worry,’ he says, ‘for now, just listen. You see, Billy, if you play your cards right, they’re going to make you immortal too.’

I try to listen. But I can’t hear them. I can see that Brian Clough is talking, he is animated and Brylcreemed in a green sports jacket; I see Sir Alf, just as I remember him, quiet and controlled, neat and tidy in his England blazer; I see Shanks in his red shirt and matching tie and Don Revie, looking glum with his thick shredded-wheat sideburns; and Sir Matt, blimey Sir Matt Busby, nonplussed and immaculate. I see them all, and I wonder what on earth is going on. Why are they here? Why am I here?

Gerry Higgs reads my mind. ‘Just listen, Billy,’ he whispers quietly but firmly. So I do. And now, suddenly I can hear them as well as see them. Cloughie is in full swing.

‘No, Don,’ he says in that piercing nasal voice, ‘the game of football is not simply about winning, it’s about winning properly, it’s about playing the game how it was supposed to be played. And kicking and cheating is not how the game is supposed to be played.’

Don Revie blusters a response: ‘Brian, I’m not rising to that, and the reason I’m not rising to that is two league titles, the FA Cup, a Cup Winners’ Cup, two Inter-Cities Fairs Cups and the League bloody Cup, that’s why.’

The other three groan. ‘Mr Revie,’ says Sir Alf, ‘Mr Clough. Please, this isn’t getting us any further. You both know the issue that we are here to discuss today.’

‘Well, we know exactly where you stand, Alf,’ says Brian Clough, curtly.

‘Thank you, Brian,’ says Sir Alf with a school teacher’s sarcasm before adding, ‘Sir Matt, I believe we haven’t heard from you on the question before us – what takes precedence: winning or entertaining, style or results.’

Sir Matt thinks for a second, his lips turning over. ‘Well,’ he says in his quiet, Glaswegian drawl, ‘no one ever remembers the losers do they? But if you can manage both to entertain and win, then you’re not far off.’

Shanks joins in, in his more abrasive Glaswegian drawl: ‘The question isn’t about winning or entertaining, I mean we’re not clowns or circus horses; it’s about making the working man who pays his money on a Saturday afternoon happy and proud, so that when he goes back to the factory or the shop floor on the Monday, he feels valuable, vindicated.’

‘Aye,’ says Sir Matt, ‘but in that pursuit we can’t allow football to lose its charm can we?’

I turn to Gerry Higgs. ‘What are they talking about?’ I say. But what I really want to know is what it all has to do with me.