По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

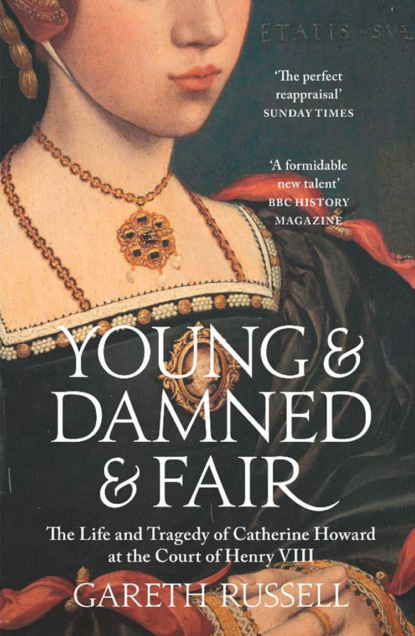

Young and Damned and Fair: The Life and Tragedy of Catherine Howard at the Court of Henry VIII

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Like most girls with a similar background, Catherine had grown up with servants, but the sheer number she saw as she was led across the drawbridge of her grandmother’s pretty moated manor at Chesworth could not have been a familiar sight.5 (#litres_trial_promo) Even if widows usually kept smaller households than a married noblewoman, the scale of the dowager’s establishment would have been difficult to comprehend for a young girl who had spent her infancy at the mercy of her father’s financial fluctuations. As the fourth highest-ranking woman in the kingdom, Agnes Howard did not keep a small household.6 (#litres_trial_promo) It would have been considered unseemly for her to do so. Etiquette guides from the time suggested it was appropriate for a duke or duchess to have about 240 servants.7 (#litres_trial_promo) As with most manners manuals, this was only a guideline, and some peers, such as the late Duke of Buckingham who employed nearly 500, preferred to live on the larger side.8 (#litres_trial_promo)

In the courtyard at Chesworth House, or Chesworth Place as it was sometimes known, Catherine got her first sight of the dozens of men and women who attended her grandmother.9 (#litres_trial_promo) The chief household officers, like the steward who essentially ran the establishment, the treasurer, and the chaplain, Father Borough, who looked after the house’s religious valuables and spiritual needs, wore cloaks sporting the dowager’s personal coat of arms in bright threads as they walked to or from their offices, all of which were located within the house proper. The chaplain’s deputy, the almoner, was in charge of arranging for charity to be given to the local poor and for any food that was left uneaten to be distributed at the manor gates. Valets, whose job was very different to their more famous Edwardian counterparts, might be on their way to check on the grain stock in the stables, while young grooms cleaned out the stalls nearby. Little pageboys, the only servants likely to be on a pittance of a salary or none at all, ran through the house carrying messages, fulfilling errands from their superiors, and trying to find time to attend training to work in another part of the household once they were older. The servants certainly had enough tasks to keep them occupied. Chesworth had its own orchard, slaughterhouse, large kitchens, a pantry to oversee the production and storage of bread, a buttery that stored the manor’s ale, beers, and wine, and a great hall where the household dined and the dowager could entertain her guests. A career in service was not considered in any way demeaning – society was hierarchical, and the rewards and security offered by employment with the aristocracy were substantial. All the servants wore uniforms and they were expected to conform to expectations that a good servant should be ‘neatly clad, his clothes not torn, hands and faces well washed and head well kempt’.10 (#litres_trial_promo)

As Catherine was ushered down Chesworth’s long corridors, the signs of her grandmother’s fortune were everywhere. This was a woman so wealthy that she kept £800 in silver around the house in case of an emergency; to give an idea of the scale of that hoarding, one of Catherine’s aunts had been expected to maintain a family and a household on about £50 a few years earlier, another lived comfortably on £196.11 (#litres_trial_promo) Cleaners bustled around placing reeds and rushes on the floor or sweeping them away for hygiene’s sake once they became too dirty. When they entered the dowager’s presence, Catherine and her brother were expected to bow or curtsey and to repeat that action in miniature every time she asked them a question, ‘otherwise, stand as still a stone’.12 (#litres_trial_promo) Like their servants, they were taught that it was impolite to sigh, cough, or breathe too loudly in the lady of the house’s presence.13 (#litres_trial_promo)

The abundance on display at Chesworth underscored why Edmund Howard was considered such a failure by his contemporaries. Consumption and display were part of the nobility’s duty, a clause in the social contract, by which they generated work for those around them and upheld the class system whose origins were believed to mirror Heaven’s. As part of his Christmas celebrations a few years earlier, Catherine’s uncle Thomas, Duke of Norfolk, had hosted a dinner for 580 guests one night and then another for 399 five days later.14 (#litres_trial_promo) A frugal aristocrat was a source of universal contempt in the sixteenth century; an indebted one even more so.

The Dowager Duchess of Norfolk was only fifty-four years old when Catherine first came into her care. The daughter of two gentry families from Lincolnshire, Agnes had come to the late duke’s attention when his first wife, Agnes’s kinswoman, passed away. Agnes’s brother Philip had then been the duke’s steward, a position often given to members of one’s extended affinity, and despite – or because of – the fact that he was nearly thirty-five years older, the duke was sufficiently smitten with Agnes’s charms to marry her regardless of the fact that she brought him little in the way of a dowry. She was thus technically Catherine’s step-grandmother, since Edmund was born from the duke’s first marriage.

Agnes’s late husband had left her twenty-four manors, and the tetchy, opinionated dowager used them to finance a life of luxury and convenience, expressing her opinions as and when they came to her. She wrote chatty letters full of unsolicited medical advice to Cardinal Wolsey, perhaps patronised poets including, quite possibly, the famous John Skelton, and made sarcastic quips at the expense of everyone from the royal court to her stepson the Duke of Norfolk.15 (#litres_trial_promo) During an outbreak of the plague in 1528, she told a visitor that the reason the sickness had affected some of the duke’s servants was the slipshod management of his household staff.16 (#litres_trial_promo) Time was to show that Agnes did not have a firm hand on the rudder of her own retinue either, but like most witty people she did not let accusations of hypocrisy stand in the way of a memorable put-down. She was a generous employer, an inveterate gossip, and conscious of the magnificence of her position – one of the many jewels she owned was a personalised initial ‘A’, crafted from pearls and set with diamonds.17 (#litres_trial_promo) To her wards, the dowager duchess was a strict but inconsistent guardian. The pearls, the diamonds, and the lady herself were often away from Catherine for extended periods, mainly at court.18 (#litres_trial_promo)

In the meantime, Catherine settled into life at Chesworth and its acres of fine deer-hunting country.19 (#litres_trial_promo) Our image of a rough-and-tumble Tudor England, replete with belching men with earthy appetites gnawing at chicken legs, and buxom serving wenches, is not a world that Catherine or her contemporaries would have recognised. From infancy, she was expected to learn etiquette and to behave appropriately. Guides and manuals from the era laid out in great detail how the children of the gentry and nobility should behave from the moment they woke up in the morning – ‘Arise from your bed, cross your breast and your forehead, wash your hands and face, comb your hair, and ask the grace of God to speed you in all your works; then go to Mass and ask mercy for all your trespasses. When ye have done, break your fast with good meat and drink, but before eating cross your mouth, your diet will be better for it. Then say your grace – it occupies but little time – and thank the Lord Jesus for your food and drink. Say also a Pater Noster and Ave Maria for the souls that lie in pain’ – to how long they should nap and how they should enter a room.20 (#litres_trial_promo) When Catherine was brought into her grandmother’s company she was expected to ‘enter with head up and at an easy pace’ and say ‘God speed’ by way of greeting, before sinking into a curtsey.21 (#litres_trial_promo) Obeisance was worked on ad nauseam. A clumsy dip was an embarrassment that no girl could afford in Tudor high society; one Howard had a servant repeat a perfect bow a hundred times after the poor man had been in such a rush that he admitted his previous attempt had been made on ‘a running leg’.22 (#litres_trial_promo) Catherine was told to look straight at whoever was speaking to her, to listen carefully to whatever they were saying, to make sure they knew that she was paying attention – ‘see to it with all your might that ye jangle not, nor let your eyes wander about’ – and ‘with blithe visage and diligent spirit’ set herself to the task of being as charming and interesting as possible. Her anecdotes and stories should be entertaining and to the point, since too ‘many words are right tedious to the wise man who listens; therefore eschew them’.23 (#litres_trial_promo) Above all, she must learn to act like a lady in front of her relatives – to stand until they told her otherwise, to keep her hands and feet still, never to lean on anything, or scratch any part of herself, even something as innocuous as her face or arms.24 (#litres_trial_promo)

This curriculum was part of the rationale behind the farming out of English aristocratic children to their relatives, a custom which foreign visitors often found peculiar. It was believed that parents might spoil or indulge their own children and thus neglect their education. Even if Edmund had not gone to Calais, Catherine would at some point probably have found herself attached to the dowager’s household. It was not just her new home, but her classroom and her finishing school where she would learn by example to behave like the great ladies of her family. Like the generation before her, Catherine was taught that good manners were essential to ‘all those that would thrive in prosperity’.25 (#litres_trial_promo) Etiquette was drilled into her at a young age and into hundreds of other girls just like her. One of her cousins was praised for being ‘stately and upright at all times of her age’ and never ‘diminishing the greatness of birth and marriage by omission of any ceremony’.26 (#litres_trial_promo) There were rhymes to help her remember the rules of placement, books aimed at children and adolescents that stressed how rude it was to point or to be too demonstrative in conversation – ‘Point not thy tale with thy fingers, use not such toys.’ There were rules that would hardly be out of place in a modern guide, such as enjoinders to keep one’s hands ‘washèd clean / That no filth in thy nails be seen’, not to talk with your mouth full, to keep cats and dogs away from the dinner table, and to only use one’s best dinner service for distinguished guests; but there were also instructions on where to put cutlery, how to cut bread (it was never to be torn with the hands), and a culture that almost elevated propriety into a religious duty.27 (#litres_trial_promo) One children’s textbook on the proper way of doing things began with:

Little children, draw ye near

And learn the courtesy written here;

For clerks that well the Seven Arts know,

Say Courtesy came to earth below,

When Gabriel hailed Our Lady by name,

And Elizabeth to Mary came.

All virtues are closed in courtesy,

And vices all in villainy.28 (#litres_trial_promo)

They were lessons that Catherine swallowed whole. For the rest of her life, she remained devoted to the niceties. Few things seemed to cause her greater stress or anguish than the fear that she might make a mistake in public. She seldom did. Compliments on her polite gracefulness followed her into the grave.

This decorum subjugated and elevated Catherine, for while it kept her firmly kowtowing at the feet of her guardian, it also affirmed her superior position to those around her. Since the Victorian era, when the cult of domesticity was at its height, many writers have bewailed Catherine’s childhood as one of gilded neglect in which the poor young girl was cast adrift by a ‘proud and heartless relative’ to live amongst a group of servants who delighted in corrupting her.29 (#litres_trial_promo) However, on looking closely at all the available evidence that has survived from Catherine’s life at Chesworth House, it is difficult to escape the conclusion that throughout her time there she was treated differently to the other young people. In almost every instance, it was Catherine who remained in control of her roommates, Catherine who confidently issued orders and had access to all the chambers and keys of the mansion. If she or her brother Henry entered a room, the servants were supposed to back away discreetly. This did not mean that they flung themselves against the wall, more that they gave them space, and they were expected to continue paying them attention for as long as they were speaking.30 (#litres_trial_promo) Catherine was initially one of only two people under the roof who was the grandchild of a duke, and the deference she was shown throughout her childhood, even by those she counted as close friends, nurtured her confidence and habit of command.

When the household ate, Catherine and her brother were on display, both before the rest of the household and under the watchful eye of the dowager or, if she had gone to court, her steward. At meals, often taken in the Great Hall, if the dowager was present and showed Catherine a sign of affection, such as allowing her to take a drink from the same cup, Catherine knew to reach out with both hands as she took it, then to pass it back to the servant who had brought it over to her. Even if there were no guests and the duchess chose to dine more privately, her establishment sat in order of precedence. Before Catherine and her family arrived in the hall, the tables were wiped down, then three layers of fresh linen were spread, with care taken to ensure each hung evenly. Eight loaves of the best bread to come out of the bakery that day were put at the top table, while servants with napkins slung from their necks to their arms covered the dowager’s cutlery with a cloth until she was ready to use it. If a servant was in doubt about the way to fold the linen or wrap the bread before consumption, there were etiquette manuals for that, as well. Basins with hot and cold water for washing one’s hands were brought out and last-minute checks conducted to make sure the salt was ‘fine, white, fair, and dry’ as required.31 (#litres_trial_promo) The dowager’s carvers would sharpen their knives before the meal, politely holding them with no more than two fingers and a thumb when it came time to carve the meat. It was a time that regarded carving as an art, with textbooks produced specifically to discuss the correct way to slice and serve.32 (#litres_trial_promo)

One place where etiquette did relax was the maidens’ chamber, the room where Catherine slept, in essence a form of dormitory, such as might be found in a traditional boarding school. Certainly, the maidens’ chamber engendered similar feelings of camaraderie and corresponding lack of privacy. Bedrooms were a rare luxury in Tudor households; sharing beds was common and sleeping in group accommodation even more so. (The dowager’s dependants were lucky to have beds; many lesser households handed out straw mattresses and glorified sleeping bags.) In the maidens’ chamber, Catherine bunked down with other young women in her grandmother’s care and service. She befriended the forceful and brash Joan Acworth, who had a string of beaux and the confidence of a girl who expected life to treat her well; there was also Alice Wilkes, who seems to have enjoyed agreeing with the prejudices of whoever she was gossiping with at the time, as well as girls related to the dowager’s natal family, such as young Katherine Tilney. With these comrades, Catherine wiled away an unremarkable early adolescence. Some of her friends, like Joan, were a few years older, others were the same age or a little younger.33 (#litres_trial_promo)

For almost half a century, our views on medieval and early modern childhood have been influenced by the work of the late French historian Philippe Ariès, whose book Centuries of Childhood: A Social History of Family Life argued that childhood was a relatively modern concept, alien to the Middle Ages or the sixteenth century with their detached style of parenting that sought to accelerate an infant’s path to adulthood.34 (#litres_trial_promo) This theory has been comprehensively debunked in recent years, and ample evidence survives, both in the relevant documents and from excavated toys belonging to medieval children, to prove that they were recognised as a separate category. Games and dolls existed for children; there were debates on the different stages of infancy; the Virgin Mary and Saint Nicholas were popular heavenly protectors of the young. By the standards of many people at the time, Catherine enjoyed a youth that could be described in positive terms – if not as idyllic, then certainly as privileged, affectionate, and happy. She was sincerely liked by many of the people at Chesworth, who appreciated the loyalty she showed towards her family’s servants, the effort she exerted to help them, her high spirits, her generosity, and her sense of mischief and fun. Life could of course be cut short in infancy, and youth could be butchered by an arranged marriage, but in Catherine’s case there is no reason to believe that she endured an unhappy or neglected childhood or adolescence.

Festivals, usually religious ones, shaped the calendar. The feast of St George, England’s national saint, and May Day, the start of summer, brought a flurry of celebrations. The twelve days of Christmas, from Christmas Day to the Feast of the Epiphany, were an especially busy time. The Christmas log, usually ash emitting a festive green flame, burned in the great fireplace,35 (#litres_trial_promo) and carols, their melodies faintly reminiscent of a dance, replaced the usual, more sombre hymns. Fine food was laid on by and for the dowager’s staff; wine, ale, and mead fuelled the party spirit – the English had a reputation for being great drinkers – while entertainments marked each passing day. Midnight Mass on Christmas Eve was a tradition that stretched back a millennium by the time Catherine huddled inside the local chapel to commemorate the Saviour’s arrival. A troupe of itinerant actors might arrive, or have been sent for, to perform a nativity play, another tradition which has survived but evolved to the present day. Symbolism and sentiment pervaded a Tudor Christmas – the holly hung throughout the house emphasised the presence of Easter in the Christmas story, sorrow amid joy, with the holly’s prickles alluding to Christ’s crown of thorns at His crucifixion, and its berries to His spilled blood. Saint Francis of Assisi had taught that even animals should share in the joyfulness of the season, originating the custom that cattle, horses, and pets should be given extra food on Christmas morning, and sheaves of corn should be left out to feed the birds struggling through winter.36 (#litres_trial_promo)

In the manor house’s rooms, boughs were built and hung by servants and members of the family. Evergreens were bound together and little gifts wrapped around them, with holders for candles added before the whole thing was hoisted high enough for people to stand underneath it. Mistletoe dangled from the centre of the bough, thus explaining its nickname ‘the kissing bough’. The evergreen bough’s candles were lit for the first time on Christmas Eve, then again every night until Twelfth Night, the colloquial name for the Feast of the Epiphany, when the Magi had arrived at the manger in Bethlehem.37 (#litres_trial_promo) The boughs were a source of mirth and merriment throughout Yuletide, with mummers or musicians often ending their performance beneath them for comic effect or hopeful flirtatiousness. Unfortunately, Catherine soon took to kissing musicians, in other parts of the house, without the excuse of Christmas revelry.

To tell the story of Catherine’s early romances and the role her family’s servants played in them, it is necessary to introduce her aunt, Katherine, a regular presence after Catherine left Edmund’s care but one who has hitherto been almost completely ignored in most accounts of Catherine’s life. The elder Katherine Howard’s impact on the journey of the younger was significant, and both began spending more time with the dowager in the same year. Katherine’s betrothal to Sir Rhys ap Gruffydd before her father’s funeral in 1524 has already been mentioned; the marriage ended in a tragedy that nearly destroyed Katherine.

A year after her father’s death and a few months into her marriage, the elder Katherine Howard’s grandfather-in-law died. An early supporter of the Tudor claim to the throne and a stalwart loyalist ever since, the old man’s position as the monarchy’s satrap in south Wales was expected to pass to his grandson and heir, Rhys, who was in his early twenties.38 (#litres_trial_promo) However, mourning had barely concluded before the government appointed the thirty-six-year-old Lord Ferrers instead. The decision was widely perceived as a humiliation for a family who had devoted their lives to serving the Tudors, and the sting worsened when young Rhys was excluded from the council that advised the royal household’s outpost in Wales. The marriage between Katherine and the attractive but hotheaded Rhys was a happy one, and she was outraged on her husband’s behalf, particularly since she believed that the decision to elevate Lord Ferrers, who had, after all, been judged too incompetent to serve as her brother’s successor as Lord Lieutenant of Ireland four years earlier, was part of a deliberate policy to humble her husband’s family.39 (#litres_trial_promo) When Rhys and two of his servants were set upon by an unknown gang as they travelled past Oxford University, she began to suspect that Ferrers meant to harm or kill him.40 (#litres_trial_promo) Rhys and his family were popular in Wales; a contemporary noted that ‘the whole country turned out to welcome him, and this made Lord Ferrers envious and jealous’. When Ferrers overplayed his hand and arrested Rhys for disturbing the peace, Katherine rallied hundreds, including the Bishop of Saint David’s and many representatives of the local gentry, who marched with her on Carmarthen Castle.41 (#litres_trial_promo) Katherine threatened the castle under cover of darkness, making sure to display her strength through the guise of delivering a message that asked for her husband and his men to be freed. If they were not, then she promised Ferrers that her men would burn down the castle door to fetch them, a threat which rather undercut her claims that she had no intention of causing further disturbances. Ferrers managed to disperse Katherine’s supporters, but the lull was temporary. Chaos began to spread in the region. Servants of the two factions were ambushed and killed, Rhys was freed, only to be taken once more, Katherine and her men attacked one of Ferrers’s homes, lives were lost and property ruined. In his letters to his superiors in London, Lord Ferrers described Katherine and Rhys as leaders of a ‘great Rebell[ion] and Insurrection of the people’.42 (#litres_trial_promo)

Eventually, Rhys was arrested one last time and brought to London to stand trial for treason. He was accused of discussing prophecies that concerned the downfall of the king and of conspiring with Scotland to foment another invasion. One of his own servants provided evidence against him. The case, which resulted in a conviction, was overseen by an on-the-rise Thomas Cromwell, who also helped to arrange some of the logistics of Rhys’s execution on 4 December 1531. It is unclear to what extent Rhys had been driven to contemplate allying with a foreign power in order to recapture his family’s position in south Wales; the common view at the time seems to have been that he was ‘cruelly put to death, and he innocent, as they say, in the cause’.43 (#litres_trial_promo) Allegations of financial corruption, his feud with Lord Ferrers, and the resultant threat to peace in Wales made his destruction a matter of convenience for the central government.

While we may never know exactly how much his own actions brought about Rhys’s death, we can be certain of the devastating effect it had on his widow. She had been intimately involved in her husband’s quarrel, and so the possibility that she would be accused of complicity in his alleged treason was tangible. Left to forge prospects for their three young children – Anne, Thomas, and Gruffydd – and fearful for herself, Lady Katherine followed in the footsteps of her elder brother Edmund and flung herself on the mercy of their niece, Anne Boleyn.44 (#litres_trial_promo) Once again, the family’s dark-eyed golden girl did not disappoint.45 (#litres_trial_promo) She may even have tried to limit the damage for her aunt and young cousins shortly before Rhys’s execution. Rhys had been attainted at the time of his conviction, meaning that the Crown could seize his goods and property, but his act of attainder specifically and unusually made provisions for his widow, who was left with an annual income of about £196.46 (#litres_trial_promo) If Anne could not save Rhys, she worked hard to salvage his family’s situation. It is incorrect that his two boys, both under the age of seven, were packed off to live in the care of another family, as has been stated. All three of the siblings stayed in their mother’s care, and she swiftly married Lord Daubeney, a widower nearly two decades her senior. Anne Boleyn had not had much time to deploy her matchmaking skills, and the sickly Daubeney was hardly as easy on the eye or heart as Rhys had been, but he enjoyed royal favour, and in such pressing circumstances that was more important than personal preference.47 (#litres_trial_promo) A few years later, Daubeney was created Earl of Bridgewater by Henry VIII, making Katherine a countess, but the marriage that saved her from going under with her first husband was not a happy one.* (#ulink_4e15b936-7885-519b-a18f-9ba4d8c4bba9) It was mutually miserable to the point that within three years the pair were living apart and complaining about one another to anyone who would listen.48 (#litres_trial_promo) The countess’s sons joined Catherine as their grandmother’s wards, though they had ample opportunity to see their mother who, accompanied by her maid, Mistress Philip, began to spend much of her time residing with her mother.49 (#litres_trial_promo)

The countess’s case showed the extent to which the new queen’s loyalty to her family could prove invaluable. It was not the same thing as infallible – she had saddled Edmund with a job for which he was manifestly unqualified and Katherine with a husband she came to loathe – but in difficult circumstances, Queen Anne was a worthwhile ally. Young Catherine was one of dozens of the queen’s cousins, nieces, aunts, uncles, and extended relatives who would look to her for advancement, especially in bringing them to court to serve her in lucrative obedience. In Calais, rumour had it that Catherine’s father did not plan to live out his life as a comptroller but ‘hopes to be here in the court with the King or the Queen, and have a better living’.50 (#litres_trial_promo) But court gossip was vicious and mercurial, savaging those it had once nurtured. Just as an anonymous letter years earlier had damaged Edmund’s standing in the aftermath of the Battle of Flodden, whispers on the court grapevine tried to harm the countess. ‘I have none to do me help except the Queen,’ she wrote in a letter, ‘to whom am I much bound, and with whom much effort is made to draw her favour from me.’51 (#litres_trial_promo) The more Howards around Anne, the better, and even if she was not destined to serve at the queen’s side, Catherine needed to continue learning the courtly graces. She was not going to spend her whole life at Chesworth House.

On 2 May 1536, the ground shifted beneath the family in the most devastating fashion since their defeat at Bosworth. Shortly after lunch, Queen Anne Boleyn was arrested and rowed upriver to the Tower of London, where, seventeen days later, she bowed off the earthly stage after tucking the hem of her dress under her shoes, hoping to preserve her dignity once her body collapsed forward into the straw.52 (#litres_trial_promo) Two days earlier, another of Catherine’s cousins, Lord Rochford, perished as collateral damage in the quest to ruin the queen, along with Sir William Brereton, a Welsh landowner who had once been supported by the countess’s first husband.53 (#litres_trial_promo) In seventeen days, the Howard women had been robbed of their most celebrated kinswoman, and while it is tempting to think that the people at Chesworth spoke of Anne’s fate in much the same horrified, incredulous way as distant relatives like the Ashleys or the Champernownes seem to have, it is equally possible that Catherine’s friends discussed the events of 1536 with the same unthinkingly gleeful acceptance that greets so many political or royal scandals, no matter how improbable their details.54 (#litres_trial_promo) The government’s version of events that had Anne as a bed-hopping, murderous adulteress certainly made for a good story, so good in fact that its manifest falsities still cling to popular perceptions of its victims, almost five hundred years later.

If the family was not already nervous enough, within weeks of the queen’s execution Catherine’s younger uncle Thomas was also sent to the Tower, after his secret betrothal to the king’s niece, Lady Margaret Douglas, was discovered.* (#ulink_4e09eace-ca1c-5096-8b2e-ccd45c689940) The king was apoplectic and chose to see the romance as part of a plot to place the Howards closer to the throne.55 (#litres_trial_promo) The couple were separated and while Margaret was eventually released, Thomas died of a fever after eighteen months in prison. His body was handed back to the dowager, who was granted permission to bury her son next to his father at Thetford on condition that ‘that she bury him without pomp’.56 (#litres_trial_promo)

Throughout the scandal caused by Thomas’s elopement, the Pilgrimage of Grace rebellion convulsed the north of England. Thousands rose in protest at the closure of the monasteries and the gathering pace of religious revolution. Even a young girl growing up in a country house in the south cannot have missed the changes affecting England after the break with Rome. Catherine’s family were initially sympathetic to the king’s quarrel with the pope, but by 1536 they were beginning to feel a mounting sense of dread. Edmund Howard had sworn the mandatory oath acknowledging the king as head of the Church in 1534, yet a few years later he and his colleagues in Calais were accused of failing to implement the king’s latest spiritual policies.57 (#litres_trial_promo) Even the late queen, the alleged harbinger of the English Reformation, had shown signs of swinging towards theological conservatism in the months before her death.58 (#litres_trial_promo) When news of the northern uprising reached Horsham, the dowager showed herself supremely reluctant to honour her feudal obligations and provide men to help suppress it.59 (#litres_trial_promo) Her sons and stepsons felt differently, perhaps mindful of their precarious position in the king’s favour after the events of the summer, and it was Lord William Howard who eventually had the lucky honour of kneeling at Henry’s feet with the news that the north had submitted.60 (#litres_trial_promo)

At this point, Catherine was about thirteen or fourteen years old. Sometime between her cousins’ executions and her uncle’s death, she began formal music lessons. Thirteen was a little late to start the music lessons that many children in her position had been taking from the ages of six or seven, so it is possible that she had some lessons earlier, though Catherine’s formal education does seem to have been somewhat neglected. Unlike several of her relatives, she was never singled out for praise for her musical or literary abilities. By the autumn of 1536, her schooling had focused on teaching her how to read, write, walk, talk, stand, dance, and move in a way guaranteed to please her contemporaries, but not much else.

Her principal music teacher was a young man called Henry Manox, brought in by the dowager, possibly on the recommendation of his kinsman, Robert Damport, who was already in her service.61 (#litres_trial_promo) Manox deviated little from the stereotype of an arrogant, young, emotionally impulsive musician. He set the mould for the type of man Catherine was subsequently drawn to – handsome, cocky, more brawn than brain, and passionate to the point of possessive. Several of Catherine’s friends already had romantic entanglements with the young gentlemen of the household – as with most establishments before the late seventeenth century, women were in the minority on the dowager’s staff – and Catherine and Manox began a flirtation that eventually progressed to kissing and fondling. In modern parlance, they fooled around but did not go all the way.62 (#litres_trial_promo)

This relationship forms the first piece of ‘evidence’ in a recent theory about Catherine’s life, namely that she was the victim of repeated sexual abuse throughout puberty, with Manox being the first of several men to groom her.63 (#litres_trial_promo) Variations on this narrative describe Manox as a predator or simply the first in a succession of men, such as Francis Dereham, who repeatedly raped her. The latter interpretation can only be sustained by either wilful or accidental ignorance of almost every piece of relevant surviving evidence. It requires misrepresenting Catherine’s personality, disregarding the biographical details of everyone around her, and twisting beyond recognition every comment made by most of the people who knew her. This is not to suggest that such abuse did not happen – the young Elizabeth I was molested and horribly manipulated by her stepfather, Thomas Seymour, in a relationship that was not just quite clearly one we would characterise as abuse, but which was described as such in contemporaries’ vocabulary for it.64 (#litres_trial_promo) Cases of child abuse were reported and prosecuted, and the concept was understood in the early modern era, so it is untrue to say that there was no perception of victimhood or coercion.65 (#litres_trial_promo) The memoirs of the fourteenth-century merchant’s wife Margery Kempe recounted an argument that contained a threat of what would now clearly be recognised as marital rape, if the husband did not get what he wanted.66 (#litres_trial_promo) Admittedly, Catherine herself would later claim that she had been forced into sexual relations at this stage in her life, but it can be shown that she was lying, and doing so in desperate circumstances.67 (#litres_trial_promo) Against that claim, which no one at the time believed, there is a mountain of precise evidence, from those who knew her and from the men involved, about when her relationships began, how they began, their consensual basis, and above all, Catherine’s role in ending them when she lost interest.

The idea of Henry Manox as a paedophile preying on his young charge is a grotesque one, but mercifully without any supporting detail. Manox certainly put Catherine under pressure to consummate their relationship and reacted crudely when she ended things between them, but none of this supports a hypothesis of sustained and deliberate abuse. In the first place, we do not know Manox’s date of birth, and given the average age of the group he consorted with, he was likely to have been five years older than Catherine at the very most. Furthermore, the scenario of Manox using their lessons to bully her into a sexual relationship is undercut by reading transcripts from the investigations of 1541, which prove Catherine’s lessons were actually taken by two teachers at the same time – Manox and another man, Barnes – during which Catherine would have been chaperoned.68 (#litres_trial_promo) However, if not horrible, their relationship was nonetheless inappropriate, on several levels.

Catherine began her lessons with Manox and Barnes in 1536. The attraction between Catherine and Manox seems to have been relatively slow-burning, but eventually the couple were sending each other little gifts, with a young maid called Dorothy Barwick being the first to carry tokens on Catherine’s behalf.69 (#litres_trial_promo) Manox later claimed that ‘he fell in love with [Catherine] and she with him’, but that was not how others remembered it.70 (#litres_trial_promo) More honestly and less nobly, he and Catherine found each other very attractive, and the taboo nature of their affair, particularly the difference in class, added a certain inevitable spice. To meet up alone and outside their lessons would have required significant skills of subterfuge. Catherine did not bring Manox into her shared dormitory, so where they found the time and venue to progress along the bases of physical intimacy is anybody’s guess. They had perhaps been meeting on several occasions when the dowager discovered them kissing in an alcove near the chapel one afternoon. She slapped Catherine two or three times and reiterated that they were never to be left alone together.71 (#litres_trial_promo) They did not obey her, but they had the sense to become more discreet. While it remained an open secret to many other people at Chesworth, they subsequently and successfully hid their relationship from the dowager.

They were still seeing each other in early 1538, when a young woman called Mary Lascelles arrived to serve in the household on a regular basis.72 (#litres_trial_promo) She was working as a nursemaid to one of Catherine’s infant cousins when the child’s father, Lord William Howard, the dowager’s youngest surviving son, began to spend more time in his mother’s household.73 (#litres_trial_promo) Tudor house guests sometimes stayed longer than modern tenants, so their servants ended up living and serving alongside the owner’s. Lord William, a diplomat and soldier, had recently been widowed and married again, to Margaret Gamage, the daughter of a Welsh landowner. He had one daughter, Agnes, from his first marriage and at least one son from his second by 1538. Mary the nursemaid was a prim young girl from a family who took the Reformation very seriously, and she was horrified at what she heard about her master’s niece – two fellow maids, Isabel and Dorothy, admitted to her that they had been carrying messages and love tokens from Catherine to Manox.

Concerned, Mary reached out in a spirit of servant solidarity to Manox to warn him of the danger he was in. She told him that if he had any plans to marry Catherine, they were impossible as ‘she is come of a noble house and if thou should marry her some of her blood would kill thee’. Manox was contemptuous: ‘Hold thy peace, woman. I know her well enough.’ With maximum honesty and minimal charm, he explained, ‘I have had her by the cunt and she hath said to me that I shall have her maidenhead though it be painful to her, not doubting but I will be good to her hereafter.’74 (#litres_trial_promo)

Manox’s boast shot through the gossip network of the house, flying with rumour’s customary unerring skill right to the ears of its subject. Catherine’s heart was not exactly warmed when she heard what Manox had said about her, and she ended their affair, even in the face of Manox pleading that he ‘was so far in love with her that he wist [knew] not what he said’.75 (#litres_trial_promo) Catherine, by then fifteen or sixteen, was disbelieving and unimpressed. She was firm to the point of brutal in her bad temper. During their argument, she pointed out, ‘I will never be nought with you and able to marry me ye be not.’76 (#litres_trial_promo) This comment is usually interpreted by historians as an example of snobbery on Catherine’s part – a wounding reminder that their respective backgrounds made the idea of marriage absurd. Had Catherine meant to make that point, she would have been unkind and accurate. In fact, it seems that she was actually being more specific. Manox could not marry her because he was already engaged to somebody else or already married. Catherine’s uncle William is mentioned calling ‘on him [Manox] and his wife at their own door’ shortly after Manox’s liaison with Catherine ended.77 (#litres_trial_promo) That Manox was engaged at the time he became involved with Catherine and married shortly after would explain both their comments about the improbability of their dalliance ending in marriage and her decision to keep their physical intimacy in check. If Catherine did intend to lose her virginity to Manox, despite her reticence, his comments about her and his fiancée gave her the motivation to end things before they went any further. All her life, Catherine hated to be humiliated and reacted strongly when faced with disrespect or embarrassment.

A few days after their quarrel, Catherine had softened and agreed to hear Manox out one last time. The two went for a stroll in the duchess’s orchards. Manox seems to have mistaken this promenade as a sign that the relationship might soon be back on track, but it was only well-meaning politesse on Catherine’s part. Her mood had altered, but her mind was made up, and not long after that she found a replacement for Manox in the form of Francis Dereham, her grandmother’s secretary.

* (#ulink_2ef6457f-0588-5430-9b4a-069b0d508e68) Lord Daubeney was not elevated to the earldom until 1538. However, for clarity’s sake, especially in differentiating her from her niece, the elder Katherine Howard will usually be referred to as ‘the countess’ from now on.

* (#ulink_7765f880-40f2-5509-99bb-9351752cd525) This was not the Duke of Norfolk, but his younger half brother with the same name, Lord Thomas Howard. In the same year, another of Agnes’s children, her daughter Lady Elizabeth Radclyffe, died of natural causes.

Chapter 5

Mad Wenches (#ulink_a628ed5a-98bc-54fd-b0db-cc87a6fd0abf)

For among all that is loved in a wench chastity and cleanness is loved most.

– Bartholomew of England, De proprietatibus rerum (c.1240)

Catherine never could make a clean break of things. Time and time again, she went back to pick at a wound, drawn irresistibly to the drama of the supposed farewell or the intimacy of an emotional conversation. Her tête-à-tête with Manox in the orchard only a few days after she broke off their relationship was the first recorded instance of a trait that left too many of her actions open to misinterpretation. As Manox nursed hopes of reconciliation, Catherine entered a more adult world. The dowager’s household began to spend more time at Norfolk House in her home parish of Lambeth, the Howards’ recently completed mansion on the opposite side of the river to Whitehall, the king’s largest and still-expanding palace. There, Catherine began to see more of the relatives who lived in the capital or at court – her elder half sister, Lady Isabella Baynton, visited the dowager, and their brother Henry had married and brought his new wife to live with him.

Catherine conformed to general contemporary ideals of beauty, which praised women who had ‘moistness of complexion; and [are] tender, small, pliant and fair of disposition of body’.1 (#litres_trial_promo) Contrary to the still-repeated tradition that she was ‘small, plump and vivacious’, the few surviving specifics about Catherine’s appearance describe her as short and slender.2 (#litres_trial_promo) A former courtier subsequently described her as ‘flourishing in youth, with beauty fresh and pure’.3 (#litres_trial_promo) She was comfortable with admiration and attention. Manox was not the only servant who was smitten; a young man called Roger Cotes was also enamoured.4 (#litres_trial_promo) As she got older, Catherine was given servants of her own, including her roommate Joan Acworth, who became her secretary. How much correspondence Catherine actually had at this stage in her life is unknown, but it clearly was not enough to create a crushing workload for Joan.

It was through her secretary-cum-companion that Catherine found Manox’s successor. Francis Dereham was good-looking, confident to the point of arrogance, and a rule breaker who possessed a blazing temper which Catherine initially chose to regard as thrilling proof of his affection for her. He was also a ‘ladies’ man’, who had already notched his bedpost with several fellow servants, including Joan Acworth.5 (#litres_trial_promo) Their fling had since ended, and Joan cheerfully moved on, even singing his praises to Catherine, who began to show an interest in him in the spring of 1538 – at the very most within a few weeks of ending things with Manox.6 (#litres_trial_promo)

By then, Francis had been in the dowager’s service for nearly two years.7 (#litres_trial_promo) Distantly related to her, he was the son of a wealthy family in the Lincolnshire gentry where he learned the upper-class syntax and mannerisms necessary to pass as one of the club.8 (#litres_trial_promo) The dowager was fond of Francis, and he eventually carried out secretarial work for her. When he first arrived at Chesworth House, he and his roommate Robert Damport were given tasks like buying livestock for the household, perhaps a boring pursuit but an important one considering that many aristocratic households spent nearly one-quarter of their expenditure on food.9 (#litres_trial_promo) Dereham and Damport were sent to get animals ready for the annual cull on Martinmas, a religious festival that fell every year on 11 November. Not all the livestock were killed then, and it is not true that most meat served in winter was heavily salted or covered in spices to hide its decay; households generally fed the animals intended for table with hay throughout the colder months to keep the food as fresh as possible.10 (#litres_trial_promo)