По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

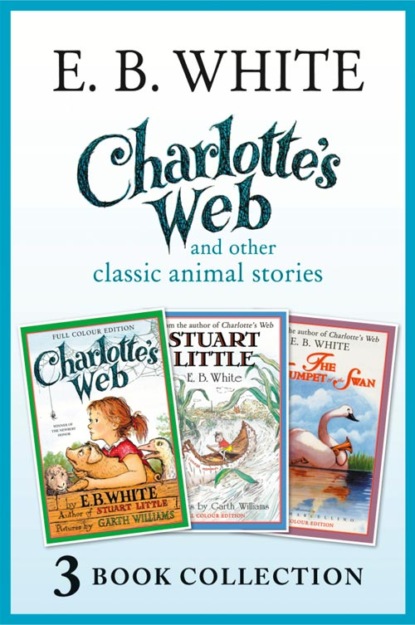

Charlotte’s Web and other classic animal stories: Charlotte’s Web, The Trumpet of the Swan, Stuart Little

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Good night!’ screamed Avery. ‘Good night! What a stink! Let’s get out of here!’

Fern was crying. She held her nose and ran towards the house. Avery ran after her, holding his nose. Charlotte felt greatly relieved to see him go. It had been a narrow escape.

Later on that morning, the animals came up from the pasture – the sheep, the lambs, the gander, the goose, and the seven goslings. There were many complaints about the awful smell, and Wilbur had to tell the story over and over again, of how the Arable boy had tried to capture Charlotte, and how the smell of the broken egg drove him away just in time. ‘It was that rotten goose egg that saved Charlotte’s life,’ said Wilbur.

The goose was proud of her share in the adventure. ‘I’m delighted that the egg never hatched,’ she gabbled.

Templeton, of course, was miserable over the loss of his beloved egg. But he couldn’t resist boasting. ‘It pays to save things,’ he said in his surly voice. ‘A rat never knows when something is going to come in handy. I never throw anything away.’

‘Well,’ said one of the lambs, ‘this whole business is all well and good for Charlotte, but what about the rest of us? The smell is unbearable. Who wants to live in a barn that is perfumed with rotten egg?’

‘Don’t worry, you’ll get used to it,’ said Templeton. He sat up and pulled wisely at his long whiskers, then crept away to pay a visit to the dump.

When Lurvy showed up at lunchtime carrying a pail of food for Wilbur, he stopped short a few paces from the pigpen. He sniffed the air and made a face.

‘What in thunder?’ he said. Setting the pail down, he picked up the stick that Avery had dropped and pried the trough up. ‘Rats!’ he said. ‘Phew! I might a’ known a rat would make a nest under this trough. How I hate a rat!’

And Lurvy dragged Wilbur’s trough across the yard and kicked some dirt into the rat’s nest, burying the broken egg and all Templeton’s other possessions. Then he picked up the pail. Wilbur stood in the trough, drooling with hunger. Lurvy poured. The slops ran creamily down around the pig’s eyes and ears. Wilbur grunted. He gulped and sucked, and sucked and gulped, making swishing and swooshing noises, anxious to get everything at once. It was a delicious meal – skim milk, wheat middlings, leftover pancakes, half a doughnut, the rind of a summer squash, two pieces of stale toast, a third of a ginger snap, a fish tail, one orange peel, several noodles from a noodle soup, the skin off a cup of cocoa, an ancient jelly roll, a strip of paper from the lining of the garbage pail, and a spoonful of raspberry jelly.

Wilbur ate heartily. He planned to leave half a noodle and a few drops of milk for Templeton. Then he remembered that the rat had been useful in saving Charlotte’s life, and that Charlotte was trying to save his life. So he left a whole noodle, instead of a half.

Now that the broken egg was buried, the air cleared and the barn smelt good again. The afternoon passed, and evening came. Shadows lengthened. The cool and kindly breath of evening entered through doors and windows. Astride her web, Charlotte sat moodily eating a horse-fly and thinking about the future. After a while she bestirred herself.

She descended to the centre of the web and there she began to cut some of her lines. She worked slowly but steadily while the other creatures drowsed. None of the others, not even the goose, noticed that she was at work. Deep in his soft bed, Wilbur snoozed. Over in their favourite corner, the goslings whistled a night song.

Charlotte tore quite a section out of her web, leaving an open space in the middle. Then she started weaving something to take the place of the threads she had removed. When Templeton got back from the dump, around midnight, the spider was still at work.

11. The Miracle (#ulink_a414743e-bf86-5782-a461-cf763043ec43)

THE NEXT day was foggy. Everything on the farm was dripping wet. The grass looked like a magic carpet. The asparagus patch looked like a silver forest.

On foggy mornings, Charlotte’s web was truly a thing of beauty. This morning each thin strand was decorated with dozens of tiny beads of water. The web glistened in the light and made a pattern of loveliness and mystery, like a delicate veil. Even Lurvy, who wasn’t particularly interested in beauty, noticed the web when he came with the pig’s breakfast. He noted how clearly it showed up and he noted how big and carefully built it was. And then he took another look and he saw something that made him set his pail down. There, in the centre of the web, neatly woven in block letters, was a message. It said:

SOME PIG!

Lurvy felt weak. He brushed his hand across his eyes and stared harder at Charlotte’s web.

‘I’m seeing things,’ he whispered. He dropped to his knees and uttered a short prayer. Then, forgetting all about Wilbur’s breakfast, he walked back to the house and called Mr Zuckerman.

‘I think you’d better come down to the pigpen,’ he said.

‘What’s the trouble?’ asked Mr Zuckerman. ‘Anything wrong with the pig?’

‘No – not exactly,’ said Lurvy. ‘Come and see for yourself.’

The two men walked silently down to Wilbur’s yard. Lurvy pointed to the spider’s web. ‘Do you see what I see?’ he asked.

Zuckerman stared at the writing on the web. Then he murmured the words ‘Some pig’. Then he looked at Lurvy. Then they both began to tremble. Charlotte, sleepy after her night’s exertions, smiled as she watched. Wilbur came and stood directly under the web.

‘Some pig!’ muttered Lurvy in a low voice.

‘Some pig!’ whispered Mr Zuckerman. They stared and stared for a long time at Wilbur. Then they stared at Charlotte.

‘You don’t suppose that that spider …’ began Mr Zuckerman – but he shook his head and didn’t finish the sentence. Instead, he walked solemnly back up to the house and spoke to his wife. ‘Edith, something has happened,’ he said, in a weak voice. He went into the living-room and sat down, and Mrs Zuckerman followed.

‘I’ve got something to tell you, Edith,’ he said. ‘You better sit down.’

Mrs Zuckerman sank into a chair. She looked pale and frightened.

‘Edith,’ he said, trying to keep his voice steady, ‘I think you had best be told that we have a very unusual pig.’

A look of complete bewilderment came over Mrs Zuckerman’s face. ‘Homer Zuckerman, what in the world are you talking about?’ she said.

‘This is a very serious thing, Edith,’ he replied. ‘Our pig is completely out of the ordinary.’

‘What’s unusual about the pig?’ asked Mrs Zuckerman, who was beginning to recover from her scare.

‘Well, I don’t really know yet,’ said Mr Zuckerman. ‘But we have received a sign, Edith – a mysterious sign. A miracle has happened on this farm. There is a large spider’s web in the doorway of the barn cellar, right over the pigpen, and when Lurvy went to feed the pig this morning, he noticed the web because it was foggy, and you know how a spider’s web looks very distinct in a fog. And right spang in the middle of the web there were the words “Some pig”. The words were woven right into the web. They were actually part of the web, Edith. I know, because I have been down there and seen them. It says, “Some pig”, just as clear as clear can be. There can be no mistake about it. A miracle has happened and a sign has occurred here on earth, right on our farm, and we have no ordinary pig.’

‘Well,’ said Mrs Zuckerman, ‘it seems to me you’re a little off. It seems to me we have no ordinary spider.’

‘Oh, no,’ said Zuckerman. ‘It’s the pig that’s unusual. It says so, right there in the middle of the web.’

‘Maybe so,’ said Mrs Zuckerman. ‘Just the same, I intend to have a look at that spider.’

‘It’s just a common grey spider,’ said Zuckerman.

They got up, and together they walked down to Wilbur’s yard. ‘You see, Edith? It’s just a common grey spider.’

Wilbur was pleased to receive so much attention. Lurvy was still standing there, and Mr and Mrs Zuckerman, all three, stood for about an hour, reading the words on the web over and over, and watching Wilbur.

Charlotte was delighted with the way her trick was working. She sat without moving a muscle, and listened to the conversation of the people. When a small fly blundered into the web, just beyond the word ‘pig’, Charlotte dropped quickly down, rolled the fly up, and carried it out of the way.

After a while the fog lifted. The web dried off and the words didn’t show up so plainly. The Zuckermans and Lurvy walked back to the house. Just before they left the pigpen, Mr Zuckerman took one last look at Wilbur.

‘You know,’ he said, in an important voice, ‘I’ve thought all along that that pig of ours was an extra good one. He’s a solid pig. That pig is as solid as they come. You notice how solid he is around the shoulders, Lurvy?’

‘Sure, sure I do,’ said Lurvy. ‘I’ve always noticed that pig. He’s quite a pig.’

‘He’s long, and he’s smooth,’ said Zuckerman.

‘That’s right,’ agreed Lurvy. ‘He’s as smooth as they come. He’s some pig.’

When Mr Zuckerman got back to the house, he took off his work clothes and put on his best suit. Then he got into his car and drove to the minister’s house. He stayed for an hour and explained to the minister that a miracle had happened on the farm.

‘So far,’ said Zuckerman, ‘only four people on earth know about this miracle – myself, my wife Edith, my hired man Lurvy, and you.’

‘Don’t tell anybody else,’ said the minister. ‘We don’t know what it means yet, but perhaps if I give thought to it, I can explain it in my sermon next Sunday. There can be no doubt that you have a most unusual pig. I intend to speak about it in my sermon and point out the fact that this community has been visited with a wondrous animal. By the way, does the pig have a name?’