По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

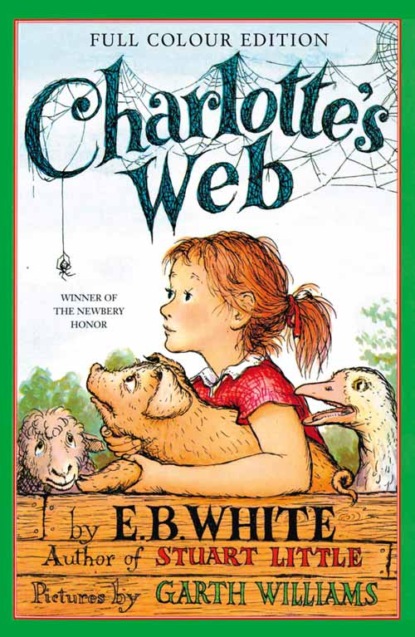

Charlotte’s Web

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘You’ll miss your freedom,’ honked the goose. ‘An hour of freedom is worth a barrel of slops.’

Wilbur didn’t care.

When Mr Zuckerman reached the pigpen, he climbed over the fence and poured the slops into the trough. Then he pulled the loose board away from the fence, so that there was a wide hole for Wilbur to walk through.

‘Reconsider, reconsider!’ cried the goose.

Wilbur paid no attention. He stepped through the fence into his yard. He walked to the trough and took a long drink of slops, sucking in the milk hungrily and chewing the popover. It was good to be home again.

While Wilbur ate, Lurvy fetched a hammer and some eight-penny nails and nailed the board in place. Then he and Mr Zuckerman leaned lazily on the fence and Mr Zuckerman scratched Wilbur’s back with a stick.

‘He’s quite a pig,’ said Lurvy.

‘Yes, he’ll make a good pig,’ said Mr Zuckerman.

Wilbur heard the words of praise. He felt the warm milk inside his stomach. He felt the pleasant rubbing of the stick along his itchy back. He felt peaceful and happy and sleepy. This had been a tiring afternoon. It was still only about four o’clock but Wilbur was ready for bed.

‘I’m really too young to go out into the world alone,’ he thought as he lay down.

4. Loneliness (#ulink_982dd350-f44c-5ef2-be11-045fc0b37f42)

THE NEXT day was rainy and dark. Rain fell on the roof of the barn and dripped steadily from the eaves. Rain fell in the barnyard and ran in crooked courses down into the lane where thistles and pigweed grew. Rain spattered against Mrs Zuckerman’s kitchen windows and came gushing out of the downspouts. Rain fell on the backs of the sheep as they grazed in the meadow. When the sheep tired of standing in the rain, they walked slowly up the lane and into the fold.

Rain upset Wilbur’s plans. Wilbur had planned to go out, this day, and dig a new hole in his yard. He had other plans, too. His plans for the day went something like this:

Breakfast at six-thirty. Skim milk, crusts, middlings, bits of doughnuts, wheat cakes with drops of maple syrup sticking to them, potato skins, left-over custard pudding with raisins, and bits of Shredded Wheat.

Breakfast would be finished at seven.

From seven to eight. Wilbur planned to have a talk with Templeton, the rat that lived under his trough. Talking with Templeton was not the most interesting occupation in the world but it was better than nothing.

From eight to nine, Wilbur planned to take a nap outdoors in the sun.

From nine to eleven he planned to dig a hole, or trench, and possibly find something good to eat buried in the dirt.

From eleven to twelve he planned to stand still and watch flies on the boards, watch bees in the clover, and watch swallows in the air.

Twelve o’clock – lunchtime. Middlings, warm water, apple parings, meat gravy, carrot scrapings, meat scraps, stale hominy, and the wrapper off a package of cheese. Lunch would be over at one.

From one to two, Wilbur planned to sleep.

From two to three, he planned to scratch itchy places by rubbing against the fence.

From three to four, he planned to stand perfectly still and think of what it was like to be alive, and to wait for Fern.

At four would come supper. Skim milk, provender, left-over sandwich from Lurvy’s lunchbox, prune skins, a morsel of this, a bit of that, fried potatoes, marmalade drippings, a little more of this, a little more of that, a piece of baked apple, a scrap of upside-down cake.

Wilbur had gone to sleep thinking about these plans. He awoke at six and saw the rain, and it seemed as though he couldn’t bear it.

‘I get everything all beautifully planned out and it has to go and rain,’ he said.

For a while he stood gloomily indoors. Then he walked to the door and looked out. Drops of rain struck his face. His yard was cold and wet. His trough had an inch of rain water in it. Templeton was nowhere to be seen.

‘Are you out there, Templeton?’ called Wilbur. There was no answer. Suddenly Wilbur felt lonely and friendless.

‘One day just like another,’ he groaned. ‘I’m very young, I have no real friend here in the barn, it’s going to rain all morning and all afternoon, and Fern won’t come in such bad weather. Oh, honestly!’ And Wilbur was crying again, for the second time in two days.

At six-thirty Wilbur heard the banging of a pail. Lurvy was standing outside in the rain, stirring up breakfast.

‘C’mon, pig!’ said Lurvy.

Wilbur did not budge. Lurvy dumped the slops, scraped the pail, and walked away. He noticed that something was wrong with the pig.

Wilbur didn’t want food, he wanted love. He wanted a friend – someone who would play with him. He mentioned this to the goose, who was sitting quietly in a corner of the sheepfold.

‘Will you come over and play with me?’ he asked.

‘Sorry, sonny, sorry,’ said the goose. ‘I’m sitting-sitting on my eggs. Eight of them. Got to keep them toasty-oasty-oasty warm. I have to stay right here, I’m no flibberty-ibberty-gibbet. I do not play when there are eggs to hatch. I’m expecting goslings.’

‘Well, I didn’t think you were expecting woodpeckers,’ said Wilbur bitterly.

Wilbur next tried one of the lambs.

‘Will you please play with me?’ he asked.

‘Certainly not,’ said the lamb. ‘In the first place, I cannot get into your pen, as I am not old enough to jump over the fence. In the second place, I am not interested in pigs. Pigs mean less than nothing to me.’

‘What do you mean, less than nothing?’ replied Wilbur. ‘I don’t think there is any such thing as less than nothing. Nothing is absolutely the limit of nothingness. It’s the lowest you can go. It’s the end of the line. How can something be less than nothing? If there were something that was less than nothing, then nothing would not be nothing, it would be something – even though it’s just a very little bit of something. But if nothing is nothing, then nothing has nothing that is less than it is.’

‘Oh, be quiet!’ said the lamb. ‘Go play by yourself! I don’t play with pigs.’

Sadly, Wilbur lay down and listened to the rain. Soon he saw the rat climbing down a slanting board that he used as a stairway.

‘Will you play with me, Templeton?’ asked Wilbur.

‘Play?’ said Templeton, twirling his whiskers. ‘Play? I hardly know the meaning of the word.’

‘Well,’ said Wilbur, ‘it means to have fun, to frolic, to run and skip and make merry.’

‘I never do those things if I can avoid them,’ replied the rat, sourly. ‘I prefer to spend my time eating, gnawing, spying, and hiding. I am a glutton but not a merrymaker. Right now I am on my way to your trough to eat your breakfast, since you haven’t got sense enough to eat it yourself.’ And Templeton, the rat, crept stealthily along the wall and disappeared into a private tunnel that he had dug between the door and the trough in Wilbur’s yard. Templeton was a crafty rat, and he had things pretty much his own way. The tunnel was an example of his skill and cunning. The tunnel enabled him to get from the barn to his hiding-place under the pig trough without coming out into the open. He had tunnels and runways all over Mr Zuckerman’s farm and could get from one place to another without being seen. Usually he slept during the daytime and was abroad only after dark.

Wilbur watched him disappear into his tunnel. In a moment he saw the rat’s sharp nose poke out from underneath the wooden trough. Cautiously Templeton pulled himself up over the edge of the trough. This was almost more than Wilbur could stand: on this dreary, rainy day to see his breakfast being eaten by somebody else. He knew Templeton was getting soaked, out there in the pouring rain, but even that didn’t comfort him. Friendless, dejected, and hungry, he threw himself down in the manure and sobbed.

Late that afternoon, Lurvy went to Mr Zuckerman. ‘I think there’s something wrong with that pig of yours. He hasn’t touched his food.’

‘Give him two spoonfuls of sulphur and a little molasses,’ said Mr Zuckerman.

Wilbur couldn’t believe what was happening to him when Lurvy caught him and forced the medicine down his throat. This was certainly the worst day of his life. He didn’t know whether he could endure the awful loneliness any more.