По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

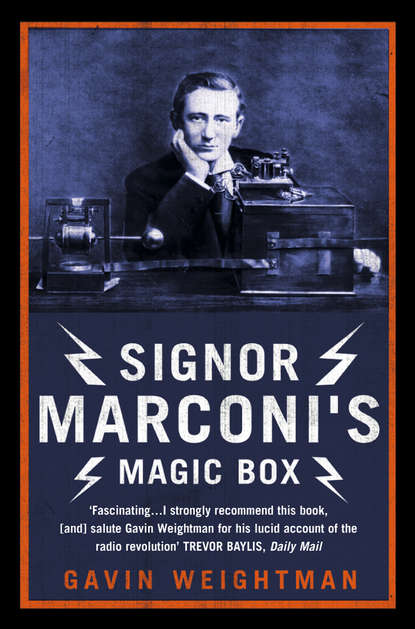

Signor Marconi’s Magic Box: The invention that sparked the radio revolution

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Lavernock Point is about sixty feet above sea level. Marconi had an aerial put up which rose a further sixty feet in the air, and was topped with a zinc cylinder connected to a receiver which had been set up to record signals in Morse code on a tickertape. Another wire went from the receiver down the cliff to the seashore. The transmitter, firing off a crackle of sparks, was three miles away on Flatholm Island. For two tense days nothing came through on the Lavernock receiver. In desperation, Marconi had the receiver taken down to the beach below the cliff, to see if that made any difference. Almost instantly it began to work.

While William Preece did not really grasp the significance of the occasion, an amazed Professor Slaby certainly did. ‘It will be for me an ineffaceable recollection,’ he said later. ‘Five of us stood round the apparatus in a wooden shed as a shelter from the gale, with eyes and ears directed towards the instruments with an attention which was almost painful, and waited for the hoisting of a flag which was the signal that all was ready. Instantaneously we heard the first tic tac, tic tac, and saw the Morse instrument print the signals which came to us silently and invisibly from the island rock, whose contour was scarcely visible to the naked eye – came to us dancing on that unknown and mysterious agent the ether!’ He wrote up an account of what he had witnessed for the American Century Magazine, which was published in April 1898.

In January, 1897, when the news of Marconi’s first successes ran through the newspapers, I myself was earnestly occupied with similar problems. I had not been able to telegraph more than one hundred metres through the air. It was at once clear to me that Marconi must have added something else – something new – to what was already known, whereby he had been able to attain to lengths measured by kilometres. Quickly making up my mind, I travelled to England, where the Bureau of Telegraphs was undertaking experiments on a large scale. Mr. Preece, the celebrated engineer-in-chief of the General Post-Office, in the most courteous and hospitable way, permitted me to take part in these; and in truth what I there saw was something quite new. Marconi had made a discovery. He was working with means the entire meaning of which no one before him had recognised. Only in that way can we explain the secret of his success.

Slaby hurried back to Germany with Marconi’s secret, and set to work replicating as best he could the brilliant success of the Bristol Channel experiment.

Having returned to my home, I went to work at once to repeat the experiments with my own instruments, with the use of Marconi’ s wires. Success was instant … Meantime the attention of the German Emperor had been drawn to the new form of telegraphy … For carrying out extensive experiments, the waters of the Havel River near Potsdam were put at my disposal, as well as the surrounding royal parks – an actual laboratory of nature under a laughing sky, in surroundings of paradise! The imperial family delight to sail and row on the lakes formed by the Havel; therefore a detachment of sailors is stationed there during the summer, and I was permitted to employ the crews as helpers.

And so it was that Marconi’s first benefactor, William Preece, had unwittingly enabled the nation which was for many years to be a bitter rival of Britain in the development of wireless telegraphy to indulge in a blatant piece of industrial espionage. With the backing of Kaiser Wilhelm II, who wanted Germany to excel in all fields of technology, and demanded that scientists be given state backing, Professor Slaby joined forces with others to develop a Teutonic version of the Italian’s new and quite magical means of communication. Meanwhile, Preece established his own induction wireless link across the Bristol Channel, and remained sceptical about the potential of Marconi’s use of Hertzian waves.

However, the City of London was mightily impressed. The potential value of what Marconi had demonstrated out on Salisbury Plain and at Toynbee Hall, and now across the Bristol Channel, lay, as far as the City investor was concerned, almost entirely in the patent rights. If an exclusive legal claim to the mechanism in the magic boxes could be established, this patent could be sold around the world, bringing instant riches. As early as March 1896, barely a month after his arrival in London, Marconi was writing to his father at the Villa Griffone with details of offers that were being made to him by various members of the extensive family contacts of the Jamesons. There was a Mr Wynne, who was related to his cousins the Robertsons, offering £2400 if Marconi would allow him to set up a company in which he would be given half the shares. Then there was another cousin, Ernesto Burn, a lieutenant in the Royal Engineers, who told Marconi he had a friend who had been paid £10,000 by the British government with a stipend of £2000 a year for ‘a discovery useful to the army’.

While Marconi, staying in Bayswater with his mother, conducted a frantic round of meetings in an effort to find a backer for his invention, his father offered advice which reflected his hope that Guglielmo would cash in as fast as he could and return with his spoils to buy a property near the Villa Griffone. Some solace from home arrived in two barrels of Griffone wine, which Marconi arranged to have bottled. In his letters home he pleaded not for wine but for the funds to pay for patent rights not only in England but in Russia, France, Italy, Germany, Austria, Hungary, Spain, India and the United States. In January 1897 he had written to his father:

I met two American gendemen who are willing to acquire my patent rights for the United States of America … I understand they would give me £10,000 divided as follows: four thousand immediately and six thousand when the patent is granted by the American Government … I believe it may be better for me to accept one of these early offers … even in the case something goes wrong with the other applications I would still have made a considerable profit.

A sense of urgency, of being on the brink not only of international fame but of a fortune, runs through the letters to old Giuseppe, and was the driving force in Marconi’s life after his arrival in London. This conviction that they were onto something which could bring them all riches was evidently shared by his mother’s side of the family, and their willingness to gamble a small fortune on Marconi arose from the pressure to prevent others from profiting from his invention. There was, at the same time, an underlying anxiety about the validity of the young man’s claim to have devised a genuinely unique technology, for in a very real sense every piece of his ingeniously fashioned and beautifully crafted equipment was derived from the experimental work of others. Marconi himself was acutely aware of this, and it took the very best patent lawyers in London months to find a form of words which amounted to a convincing case that in assembling bits and pieces devised in laboratories in Germany, France, England and Italy – coils, spark gaps and ‘coherers’ – Guglielmo Marconi had arrived at a unique arrangement.

Marconi’s blood had run cold when in 1896 he met on Salisbury Plain a companionable young man, Captain Henry Jackson of the Royal Navy, who told him that he too had been experimenting with Hertzian waves, and had actually built and operated a wireless telegraphy system which had been given a trial run on a battleship, with some success. According to Captain Jackson, as Marconi listened he became crestfallen, and it was only when the naval officer assured him that this work was top secret, and there were no plans to apply for a patent, that he cheered up. William Preece, during his brief honeymoon with Marconi, would insist on basking in the reflected glory of having ‘discovered’ the Italian inventor, and continued to lecture to audiences around the country on the great value this new sort of wireless telegraphy might have for lightships and lighthouses. Preece’s promotion of Marconi infuriated one of the leading English scientists of the day, Professor Oliver Lodge of Liverpool University.

Preece and Lodge had a longstanding feud about the best way to erect lightning conductors – the Post Office had hundreds of them, to protect the telegraphy system from storms – and Lodge could not abide what he regarded as Preece’s ill-informed recounting of the miraculous Marconi invention. An undignified spat broke out on the pages of The Times. ‘It appears that many persons suppose that the method of signalling across space by means of Hertzian waves received by a Branly tube of filings is a new discovery made by Signor Marconi,’ Lodge wrote in a letter to The Times in June 1897. ‘It is well known to physicists, and perhaps the public may be willing to share the information, that I myself showed what was essentially the same plan of signalling in 1894. My apparatus acted vigorously across the college quadrangle, a distance of 60 yards, and I estimated that there would be a response up to a limit of half a mile.’

By that time Marconi had already demonstrated that the range of wireless waves was not as limited as Lodge claimed. Lodge protested that he did not mean that half a mile was the absolute limit, and commended Marconi for working hard ‘to develop the method into a commercial success’. In the same letter he continued: ‘For all this the full credit is due – I do not suppose that Signor Marconi himself claims any more – but much of the language indulged in during the last few months by writers of popular articles on the subject about “Marconi waves”, “important discoveries” and “brilliant novelties” has been more than usually absurd.’

While this storm was brewing between his bearded benefactor and the piqued professor, the Jameson family freed Marconi from Preece’s patronage. His father Giuseppe was persuaded to put up the £300 necessary to pay for legal expenses in procuring patents. Then his cousin, the engineer Henry Jameson-Davis, raised £100,000 in the City, mostly from corn merchants connected with the Jameson whiskey business. The Wireless Telegraph and Signal Company was set up with this substantial investment, equivalent to more than £5 million in today’s money. It was a commercial venture, the sole purpose of which was to buy the patents and give Marconi the money he needed to continue his experiments. He got sixty thousand of the £1 shares, £15,000 for his patents and £25,000 to spend on research. It was a massive vote of confidence from his mother’s family and their business associates.

Henry Jameson-Davis was not acting in a sentimental fashion by raising this huge sum for his cousin. Jameson-Davis was the archetypal Victorian gendeman, a keen foxhunter who would be out with the hounds in Ireland and England as often as six times a week in the winter hunting season. He would not gamble family money on a twenty-three-year-old with an intriguing but largely untried gadget without good reason. He and the other investors hoped to make a fortune when in July 1897 the Wireless Telegraph and Signal Company opened its offices at 28 Mark Lane in the City. By buying the patent rights as soon as they were awarded, the company put William Preece and the British Post Office out of the picture, and left Marconi to get on with the work of demonstrating what a valuable invention the newly formed company owned.

Marconi anticipated that Preece would not take kindly to being supplanted by a family concern, and on 21 July 1897 he wrote to him from the Villa Griffone explaining his position. All the governments of Europe, he said, wanted demonstrations of his equipment, his patents were being disputed by the likes of Professor Oliver Lodge in England and others in America, and he needed money to refine his equipment, take out new patents and fund more ambitious experiments. His letter concluded: ‘Hoping that you will continue in your benevolence towards me I beg to state that all your great kindness shall never be forgotten by me in all my life. I shall also do my best to keep the company on amicable terms with the British Government. I hope to be in London on Saturday. Believe me dear Sir, yours truly G. Marconi.’

Naturally enough, Preece replied that the patronage of the British Post Office could no longer be continued. He showed little concern over the loss of control of the new invention, evidently taking the view that it was not going to be of much practical use anyway.

Privately, Preece was pouring cold water on Marconi’s spark transmitter in confidential memoranda to the Post Office and the government, suggesting that really there was not much future in it, and in any case the patent was probably not secure, as Oliver Lodge had a prior claim to it. In his Toynbee Hall lecture Preece had said, to the cheers of the audience, that he would see to it that the Post Office would fund Marconi. But the promised £10,000 had not been forthcoming. With his family firm, Marconi now had the funds and the freedom to set up whatever experiments he wished. As he had become convinced that the most promising practical use of wireless was sending messages from ships to shore, he headed for the coast to test the range and flexibility of wireless telegraphy.

6 (#ulink_27a0c099-a2e7-58fa-9675-42d66aa7d19a)

Beside the Seaside (#ulink_27a0c099-a2e7-58fa-9675-42d66aa7d19a)

This was the heyday of the English seaside resort, before the new fashion for sunbathing drew the wealthy to the Mediterranean in the summer months. The luxury Blue Trains steamed down to the French Riviera only in winter, when the mild climate attracted the English aristocracy who developed the resorts of Nice and Cannes. Queen Victoria herself liked to stay in Hyères, near Toulon, but not beyond May, when the heat became unbearable and everyone returned north, the French to Honfleur and Deauville on the Normandy coast, and the English to their favoured grand hotels in Eastbourne, Bournemouth and other fashionable seaside towns.

The railways had opened up many resorts to day-trippers from London, and the south coast of England was becoming socially segregated as the ‘quality’ sought refuge from brash day-tripper resorts like Brighton in the more exclusive havens and coves. Aristocratic and royal families from all over Europe would spend time in Cowes on the Isle of Wight, a short ferry-ride from the coast. In August there was Cowes Regatta, a gathering of the wealthy and the upper crust who raced their huge yachts and enjoyed a splendid social round. Queen Victoria’s favourite retreat was Osborne House, close to Cowes, and she spent most summers here in her old age, enjoying the fresh sea air as she was wheeled around the extensive grounds in her bath-chair. On the white chalk clifftops of the island were grand hotels, those on the southern coast with a view across the Channel to France. Among them was the Royal Needles Hotel at Alum Bay, on the very western tip of the island.

It was in rented rooms at the Royal Needles that Marconi established the world’s first equipped and functioning wireless telegraphy station in November 1897. An aerial 120 feet high with a wire-netting antenna was erected in the grounds, without, it seems, giving rise to any complaints from other residents. In various rooms of the hotel were pieces of equipment for transmitting and receiving, and workshops where coils of wire were wound, wax was melted for insulation, and metals filed down for experimental versions of the receiver or coherer.

The location was chosen so that Marconi could test his equipment at sea and as a means of communication between ships and the shore. In the summer months, when the coast teemed with tourists and the horse-drawn bathing machines were trundled into the chilly waters of the Channel for women bathers to enjoy a discreet dip, coastal steamers ran regularly from the pier at Alum Bay to the resorts of Bournemouth and Swanage to the west. Marconi negotiated to fit wireless telegraphy equipment to two of these, the May Flower and the Solent, so that he could test the range and effectiveness of his station at the hotel. When he and his engineers were transmitting, guests were intrigued by the crackle and hiss of the sparks which generated the mysterious and invisible rays that activated the Morse code tickertape on the ships.

English hotels offered the young inventor comfort and fine food, a place where his mother and older brother Alphonso as well as the staff of engineers he was gathering around him could stay. Though Marconi and his mother had no time to enjoy the glamorous social life of London, they were able to find some relaxation on the breezy south coast of England. After Alum Bay another station was opened at the Madeira Hotel in Bournemouth, fifteen miles down the coast. Bournemouth had many distinguished visitors and residents in the nineteenth century: Charles Darwin had stayed there in the 1860s; the beautiful Emilie Charlotte le Breton, known by her stage name Lillie Langtry, lived in a house in Bournemouth provided by her lover, the Prince of Wales, in the 1880s; Robert Louis Stevenson had written The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde in Bournemouth while recovering from ill-health; and the artist Aubrey Beardsley had only recently left the resort after a period of convalescence when Marconi arrived.

The Bournemouth station first went into operation in January 1898, just before a blizzard blanketed the south coast in deep snow. Newspaper reporters had gathered in Bournemouth, where William Gladstone, the former Prime Minister and grand old man of British politics, was seriously ill. The weight of snow brought down the overhead telegraph wires, and communication with London was cut. It was characteristic of Marconi’s opportunism and instinct for publicity that he arranged for the newly opened station at the Madeira Hotel to send wireless messages to the Royal Needles Hotel, from where they could be forwarded to London by the telegraph links from the Isle of Wight, which were still open. In the event, Gladstone recovered sufficiently to return to his home, where he died in May 1898.

Marconi fell out with the management of the Madeira Hotel – it is not clear if the dispute was about money or the nuisance his wireless station caused to other guests – and moved his station to a house in Bournemouth, and then finally to the Haven Hotel, a former coaching inn in the adjoining resort of Poole. This became a home from home for him for many years, long after the station at the Royal Needles Hotel was closed down. After a day in which the Haven’s guests were entertained by the crackling of Marconi’s aerial, the inventor would often sit down at the piano after supper. Accompanied by his brother Alfonso on the violin and an engineer, Dr Erskine Murray, on cello, the trio would play popular classical pieces as the prevailing south-west wind rattled the hotel windows. Annie Marconi often stayed to look after her son, and those evenings in Poole were among the most delicious and poignant of her life. She was to see Guglielmo less and less as he pursued with steely determination his ambition to transmit wireless signals further and further across the sea. For the time being, however, the fame he had already achieved was a vindication of her faith in him, and indeed of the great risks she had taken in her own life.

7 (#ulink_b8a16e52-a497-5ead-8d3c-95e1fdd9ade6)

Texting Queen Victoria (#ulink_b8a16e52-a497-5ead-8d3c-95e1fdd9ade6)

On 8 August 1898 the airwaves crackled with one of the first text messages in history: ‘Very anxious to have cricket match between Crescent and Royal Yachts Officers. Please ask the Queen whether she would allow match to be played at Osborne. Crescent goes to Portsmouth, Monday.’ It was sent from the royal yacht Osborne, off the Isle of Wight, to a small receiving station set up in a cottage in the grounds of Osborne House. Queen Victoria’s reply was tapped back across the sea: ‘The Queen approves of the match between the Crescent and Royal Yachts Officers being played at Osborne.’

The Queen, then seventy-nine years old, had spent much of the summer at Osborne, and could not fail to notice that something intriguing was going on a few miles to the south at the Royal Needles Hotel. Guglielmo Marconi was not only becoming something of a local figure, he had won tremendous acclaim in the press for one of the first commercial tests of his wireless telegraphy, when the Dublin Daily Express had asked him if he could cover the Kingston Regatta in Dublin Bay that July. The newspaper had been impressed by some experiments one of Marconi’s engineers had carried out on a treacherous part of the Irish coast for the shipping underwriters Lloyd’s of London. To cover the Kingston Regatta Marconi fitted up a tug, the Flying Huntress, with his equipment, and followed the yacht races at sea, sending back the latest news and positions to a receiving station on shore which then cabled the up-to-the-minute accounts to the Express’s sister paper, the Evening Mail.

The Flying Huntress was an old puffer, and looked comical with its makeshift aerial mast and a roll of wire rabbit-netting rigged up to exchange signals with the shore station in the gardens of the Kingston habourmaster’s home. In contrast to the bizarre sight of ‘Marconi’s magic netting hanging from an impromptu mast’, the Dublin Daily Express reporter found the inventor himself captivating.

A tall, athletic figure, dark hair, steady grey blue eyes, a resolute mouth and an open forehead – such is the young Italian inventor. His manner is at once unassuming to a degree, and yet confident. He speaks freely and fully, and quite frankly defines the limits of his own as of all scientists’ knowledge as to the mysterious powers of electricity and ether. At his instrument his face shows a suppressed enthusiasm which is a delightful revelation of character. A youth of twenty-three who can, very literally, evoke spirits from the vasty deep and despatch them on the wings of the wind must naturally feel that he had done something very like picking the lock of Nature’s laboratory. Signor Marconi listens to the crack-crack of his instrument with some such wondering interest as Aladdin must have displayed on first hearing the voice of the Genius who had been called up by the friction of his lamp.

There was just as much fascination with the shore station, where Marconi’s ‘chief assistant’ George Kemp, a stocky little Englishman with a handlebar moustache, an indefatigable worker who knew his masts and his ropes from his time in the Navy, and who Marconi had met through Preece at the Post Office, was tracked down by another Daily Express journalist. The ‘old navy man’ gave a down-to-earth account of the state of the art: ‘The one thing to do if you expect to find out anything about electricity is to work,’ said he, ‘for you can do nothing with theories. Signor Marconi’s discoveries prove that the professors are all wrong, and now they will have to go and burn their books. Then they will write new ones, which, perhaps some time they will have to burn in their turn.’ Of Marconi, Kemp said: ‘He works in all weather, and I remember him having to make three attempts to get out past the Needles in a gale before he succeeded. He does not care for storms or rain, but keeps pegging away in the most persistent manner.’

Yet another reporter on board the Flying Huntress described Marconi standing by the instruments ‘with a certain simple dignity, a quiet pride in his own control of a powerful force, which suggested a great musician conducting the performance of a masterpiece of his own composing’. Though he had been determined not to be overawed by this wonderful invention, the reporter confessed to a thrill when he joined Marconi in a little cabin to send a message to the shore. Having witnessed this remarkable demonstration, a devilish impulse to play with wireless overcame him.

Is it the Irish characteristic, or is it the common impulse of human nature, that when we find ourselves in command of a great force, by means of which stupendous results can be produced for the benefit of mankind, our first desire is to play tricks with it? No sooner were we alive to the extraordinary fact that it was possible, without connecting wires, to communicate with a station which was miles away and quite invisible to us, than we began to send silly messages, such as to request the man in charge of the Kingston station to be sure to keep sober and not to take too many ‘whiskey-and-sodas’.

All the English newspapers reported Marconi’s triumph at the Kingston Regatta, and the glowing descriptions of this modest young inventor and his magical abilities impressed Queen Victoria and her eldest son Edward, the Prince of Wales, known affectionately as ‘Bertie’.

The Prince of Wales spent much of his time with rich friends, and had been a guest of the Rothschilds, the banking millionaires, in Paris, where he had fallen and seriously injured his leg. In August he was to attend the Cowes Regatta on the royal yacht, and a request was made to Marconi to set up a wireless link between the Queen at Osborne and her son on the ship moored offshore. Marconi was only too happy to oblige: it was excellent publicity, and it was no concern of his if, for the time being, wireless was employed frivolously. In any case, as he later told an audience of professional engineers, it offered him ‘the opportunity to study and meditate upon new and interesting elements concerning the influence of hills on wireless communication’.

With an aerial fixed to the mast of the royal yacht and a station set up in a cottage in the grounds of Osborne House, the textmessaging service between the Queen and her son was successfully established. A great many of the guests and members of the royal family on the yacht and staying at Osborne House took the opportunity to make use of this entirely novel means of communication. The messages were received as Morse code printout, which was then decoded and written in longhand on official forms headed ‘Naval Telegraphs and Signals’. In this way a lady called Emily Ampthill at Osborne was able to ask a Miss Knollys on the royal yacht: ‘Could you come to tea with us some day (end)’, to which the reply came: ‘Very sorry cannot come to tea. Am leaving Cowes tonight (end)’. More than a hundred messages were sent, many of them from Queen Victoria showing concern for Bertie’s bad leg.

This was another triumph for Marconi. He wrote home to his father to tell him excitedly of his two weeks with the world’s most famous royal family, that Prince Edward had presented him with a fabulous tiepin, and that he was granted an audience with Queen Victoria. However, what excited him most was the discovery that he could keep in touch with a moving ship up to a distance of fourteen miles, his signals apparently penetrating the cliffs of the Isle of Wight. The newspapers loved it, none more so than a new popular publication which had gone on sale for the first time in 1896, the Daily Mail. A full-page illustration showed Marconi at his wireless set, watched by two fascinated ladies, with his signals careering off along a wavy dotted line to the aerial of the royal yacht.

As an inventor Marconi was exceptionally lucky. While others struggled to find financial backers, his contacts through his mother’s aristocratic Anglo-Irish family had given him security for at least a year or two, and the money to pay for equipment and assistants. During his brief period under William Preece’s patronage Marconi had ‘borrowed’ the old sailor George Kemp, who became his most loyal attendant. Now Kemp was on the Marconi Wireless Company payroll,* (#ulink_e4f4fbae-4cd5-5b57-b127-4196634fcd61) rigging up aerials on windswept coasts wherever they were needed, for all the world like a mariner who had found a new lease of life raising masts on land with which to catch not the wind, but electronic waves. Young as Marconi was, his dedication and single-mindedness, his gentlemanly demeanour, so different from the popular image of the ‘mad inventor’, and his continuous success inspired loyalty in his small workforce of engineers, most of whom had learned their trade in the business of telegraph cables.

Although a lot of ‘secret’ experimentation went on in the hotel laboratories on the Isle of Wight and at Poole on the south coast, Marconi was always willing to chance his luck and his reputation with very public demonstrations of wireless telegraphy. This above all endeared him to the new popular journals of the day, which had a hunger for exciting and novel discoveries, especially those which might have potential for driving forward the already wonderful advances in modern civilisation. The dapper figure of Signor Marconi, always smartly dressed, the modest Italian who spoke perfect English and who appeared to be able to work miracles with a few batteries and a baffling array of wires, was irresistible.

* (#ulink_28c24e05-e7d5-58fa-90f6-57a9f72caeea)Marconi’s name was added to the company name in February 1900. Very rapidly other Marconi companies were formed, including the Marconi International Marine Company and the American Marconi Company, both also in 1900.

8 (#ulink_3b490b46-7ba4-575e-8a27-bfb7ff481090)

An American Investigates (#ulink_3b490b46-7ba4-575e-8a27-bfb7ff481090)

Wherever Marconi went in these heady early days of his fame he was sure to have along with him a writer commissioned by the American McClure’s magazine. Founded in 1894 by an Irish émigré, Samuel McClure, McClure’s was one of the first publications to make use of the new process of photo-engraving, which put the old woodcut engravers out of business, as photographs could now be reproduced at a fraction of the cost of hand-carved illustrations. McClure’s sold for fifteen cents on the news-stands, yet it could attract such eminent writers as Rudyard Kipling and Arthur Conan Doyle. It was the policy of the magazine to invite writers of fiction to cover news events, and McClure’s fascination with Marconi resulted in a series of wonderfully colourful descriptions of the young inventor at work.

Marconi had already made the headlines with his coverage of the Kingston Regatta and his link-up between Queen Victoria and the Prince of Wales at the Isle of Wight, as well as one or two other well-publicised demonstrations of his invention. When McClure’s learned that the French government had asked him if he could send a wireless signal across the English Channel – at thirty-two miles by far the greatest distance attempted up to that time – in the spring of 1899, it decided that this had to be covered. Cleveland Moffett, a writer of fictional detective stories, and a fellow reporter, Robert McClure, brother of the magazine’s founder, were despatched to cover the historic event, and to reassure themselves and their readers that there was no trickery involved. Moffett joined Marconi on the French side, in the small town of Wimereux, close to Boulogne-sur-Mer, where thirty-five years before Annie Jameson had secretly married Giuseppe Marconi. He wrote:

At five o’clock on the afternoon of Monday, March 27th, everything being ready, Marconi pressed the sending-key for the first cross-channel message. There was nothing different in the transmission from the method grown familiar now through months at the Alum Bay and Poole stations. Transmitter and receiver were quite the same; and a seven-strand copper wire, well insulated and hung from the sprit of a mast 150 feet high, was used. The mast stood in the sand just at sea level, with no height of cliff or bank to give aid.

‘Brripp – brripp – brripp – brripp – brrrrrr,’ went the transmitter under Marconi’s hand. The sparks flashed, and a dozen eyes looked out anxiously upon the sea as it broke fiercely over Napoleon’s old fort that rose abandoned in the foreground. Would the message carry all the way to England? Thirty-two miles seemed a long way.

‘Brripp – brripp – brrrrr – brripp – brrrrr – brripp – brripp.’ So he went, deliberately, with a short message telling them over there that he was using a two-centimeter spark, and signing three V’s at the end.