По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

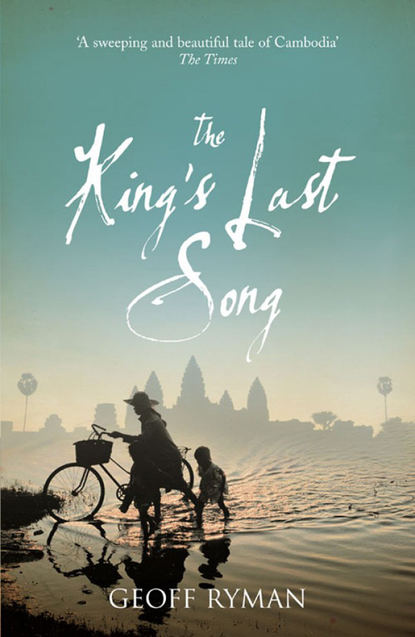

The King’s Last Song

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Look, Chubby. I came out here to give you some news. They think whoever stole the Book also got your Frenchman.’

‘What?’ Map flings himself to his feet and exclaims, ‘Chhoy mae!’ The expression means, precisely, mother-fuck.

‘Chubby, please be more polite.’ The Captain shifts. ‘I know this is bad news for you. The Army says that Grandfather Frenchman and a general took the Kraing Meas with them. One of the Army guards says the thieves took them both as well.’

Map is shaking his way into his T-shirt and trousers. ‘More like the Army got them.’

‘Or the Thais,’ says one of the guides.

‘The Thais gave us back a hundred stolen things,’ Map snaps back. He’s fed up, angry, sick at heart. ‘It’s not the Thais, it’s our own people, it’s just we want to blame the Thais. Captain, I need to go into town. Can you give me a lift back to my bicycle?’

‘Chubby. Your job is to guard the temple.’

‘Who do I value more, Captain – you or Grandfather Frenchman? You can keep your sixteen dollars a month; the Teacher pays me more. Any of you guys want two dollars? I’ll pay you two dollars to sleep in my hammock. Here’s my gun.’

Map holds his gun out to one of the guides. The guide doesn’t want to touch it. ‘You might need it, man, the Army hate you.’

‘I won’t need it. My dick shoots bullets.’

The guides hoot: Map knows no bounds. He squats down and laces up his shoes. ‘A snake bites me, she curls up and dies. A jungle cat comes to eat me, I eat her.’

‘Map, Map.’ Captain Prey shakes his head. ‘Talking that way is why you sleep in a hut.’

‘I don’t sleep in a hut. Huts give me bad dreams. I sleep like I got used to sleeping for twenty years – on the ground. Gunfire helps me sleep.’

‘Ghosts like huts,’ someone says.

Map jumps down from the causeway, three metres to the ground. His short thick legs soak up the shock and he lands like a cat on all fours. ‘I can walk to my bicycle.’

His boss chides him. ‘Chubby. I’ll give you ride.’

With an angry sniff, Map kung-fus himself onto the back of the bike. ‘OK, let’s go.’

The Captain revs the bike, then turns to him. ‘Chubby, the thing that bothers me is that really, under all the rude talk, you are a good man.’

‘Yeah, I know. I also know that life is shit and I don’t see why I shouldn’t say so.’

‘Because,’ says his boss, looking at him seriously. ‘It makes it sound like you’re shit too.’

‘You are what you eat,’ says Map and grins like a corpse.

Map is bicycling alone into Siem Reap.

The Patrimony Police don’t have enough money for motorcycles. They keep their men occupied by training. Every day, the Patrimony Police cycle all around the Western Baray or up the main hill of Phnom Bakeng.

Map always has to be the first. He boasts that he can cycle as fast as any motorbike. He certainly can cycle faster than his captain or any of the younger guys. He is the oldest man on the force. He says: from the neck up, there’s a face that should have had grown-up sons to work for me. From the neck down, I am my own sons. I have no sons, so my legs are sons for me.

He cycles now with his eyes fixed on the moon. He thinks of the famous stone portrait of Jayavarman. The stone face is white too, and it also glows, with wisdom and love. The face of the moon is the face of the King.

So what is all this about, Great King? How come someone with as many good actions as Ta Barang gets taken by pirates? Explain to me how that can be justice. Tell me how there can be any justice.

There are whole fields of angry spirits, Jayavarman. Am I the only guy who can see them? I see their hands coming out of the ground, all prickly like thistles. All around here, in the ditches, are bones and mud that used to be people. You can put out your tables of food at New Year and Pchum Ben, but these ghosts don’t want rice cakes. They want me, Jayavarman, because of what I did. So I just keep laying them down. All those ghosts. The grass in Cambodia is ghosts, the termite nests swarm with them.

And no one remembers. No one talks. They don’t want to harm the children by telling the truth. They think the truth is dust that can be raised. The truth is teeth in the air. The truth bites. Truth is thicker around us than mosquitoes.

I know who stole the Golden Book. At New Year? It’s us again, isn’t it, Jayavarman? It’s the Khmers Rouges, Angka. We’ve come back like all those vengeful spirits that don’t want to be forgotten. Just when they thought they’d paved us over, built a hotel on top of us, and made themselves rich, we jump up and take their strong man, and the barang who wants to help us. Like the spirits, we come back not because we think we can win. We just want to make this world hell. Like the one we live in.

The road is absolutely dark and still. On the last night of New Year. No one’s travelling. They’re all scared again, scared in their souls, scared all the way back to the war. Two gunshots and they’re like birds flying in panic.

We are so easily knocked down, Jayavarman. We try and try, we work so hard. We maintain our kindnesses. We smile, and help each other, and make life possible for each other. We perform our acts of merit and still our luck doesn’t change.

Acts of merit don’t work, Jayavarman.

They didn’t work for Ta Barang, they don’t work for those guides on the stone steps. So I don’t do them, Jaya. I don’t do good actions. Good actions don’t get you anything; good actions have no power. Nothing seems to have any power.

Why doesn’t anything change? Why am I stuck on a bicycle? Why are my friends not teaching college instead of swatting flies in the dark? Why do our children give up being smart?

Map imitates the children aloud to the moon. He says in English, in a child’s voice, ‘Sir, you buy cold drink, Sir? Something to eat, Sir?’

Map wants to weep for his people and their children. They wait all day in the sun to sell the beautiful cloth that is spun on bicycle wheels by people with no legs. They get up at 4.00 a.m. to buy tins of coke and bottles of water and they carry the ice four kilometres and they are six years old. ‘If you buy cold drink later, you buy from me. Promise, Sir?’

Instead of going to school.

Jayavarman answers, in the person of the moon.

Because, the moon says in a soft voice. That is the only reason. Just because. You must work very hard now to catch up.

Yeah, everybody’s ahead of us, not just the Americans, but even the Thais. The Thais come here in air-conditioned coaches and won’t use the toilets because they are too dirty. They cannot believe we ever built this city or gave them their royal language. The Vietnamese are way ahead of us, making their own motorcycles for profit.

Moonlight reflects on the paved, smooth road as if it were water. The moon on the empty road speaks again.

So. Cycle. Cycle hard, cycle fast, cycle all the way into your old age. The world won’t notice.

Work. Work without success. Grind and sweat and cheat with no merit. You are starting from the bottom. You are the lowest in the world.

Because.

‘Because,’ repeats Map.

Excuse me, King. But I know who I am.

I am a smart guy. I am a brave guy. I am a scary guy. I have power inside me, Jayavarman Chantrea, Jayavarman Moonlight. I could be anyone. I could be Hun Sen himself. So Because is why I am cycling on this road alone? Just Because? Is that all?

The moon inclines his sympathetic head. No. You are cycling to rescue Ta Barang.

Yeah, I guess I am.

The moon says, Under all the bragging, you are a respectableman, Tan Sopheaktea. Sopheaktea is Map’s real name, cruelly inappropriate. It means Gentle Face.

Другие электронные книги автора Geoff Ryman

Lust

0

0