По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

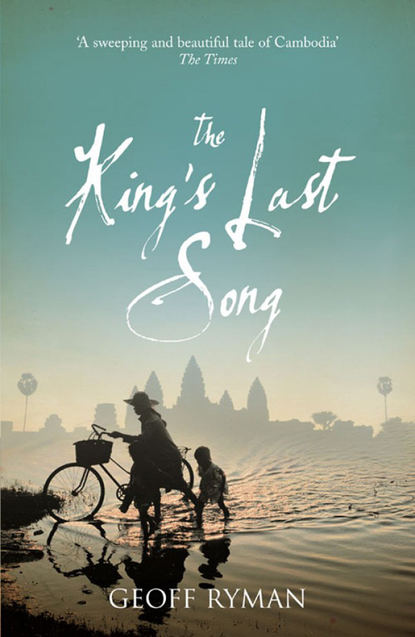

The King’s Last Song

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

And Nia was dazzled and he was struck dumb, for there was Jayarajadevi, his wife, and her smile stretched all the way to the moon.

Her smile was pulled wide by a joy she could not express, and her eyes shone. She was sheathed in gold, jewels and signs of office, surrounded by fans and fly whisks and parasols, all borne by her friends. The paraphernalia bobbed around her beautiful face like flowers.

Jayavarman stared and could not speak. People chuckled. His mouth hung open. He had a declaration to make and could not make it.

‘Lord,’ reminded Divakarapandita.

Jayavarman restored himself and stumbled rough-voiced and awkward through the words that declared and promised and established and called upon others to witness. His wife’s eyes were on him all the time.

There was feasting and dancing. The Little King’s friends hugged him, shook him, teased him and declared that they would marry too, it would give them heart for battle, they had not known until now that wives completed warriors.

The bride’s female friends warned him, shaking fingers, that he must treat their friend well or the women would take revenge. It was both a joke and serious.

Indradevi Kansru wove her way towards them, her whole body writhing with happiness. Her eyes shone almost too brightly, and she took her sister’s hand, called the Little King ‘Brother’, and said repeatedly how happy she was. It was a good marriage, and they should both count on her always as a friend. She pulled away suddenly and Jayarajadevi started after her. And stopped.

For Yashovarman was upon them. Their other friends drew back. ‘Little King,’ he said, ‘the Universal King does you a great honour.’

‘He does, oh, he does indeed!’ said Jayavarman, still buoyed up with joy like a bobbing raft.

‘I wish you well in your marriage, and wish you good heart in the coming war.’

‘Oh! The same to you, Prince!’ Jayavarman was not exactly himself, the words were not appropriate for once, but the force behind them was good hearted.

‘We will fight many wars together,’ said Yashovarman. ‘I hope I can rely on you?’

What a dangerous question. The waters of joy receded. Swiftly Jayavarman mounted the bank, the bank of politics, princes, rivalries and himself.

Jayavarman said, ‘I try to be friends with all men and certainly loyal to all my comrades in arms.’

Yashovarman whispered, ‘What if I am more than that?’

Jayavarman did not have the heart to be anything other than direct. ‘I think you will be Universal King, Yashovarman, and I intend to serve the King. For me to be loyal to the next King, my Lord Suryavarman, who is beloved by me, must die in his bed, honoured, and his ashes kept in his temple with great remembrance. Let us have a pact, Yashovarman, to preserve our Lord so that all can see he died a natural death.’

Yashovarman went very still and silent. ‘Of course,’ he said without further ceremony or display of feeling. He very suddenly smiled, and flipped the tip of the Little King’s nose. ‘What a little puppy you are.’ It could almost pass for affection. Yashovarman strode away.

Did Suryavarman see the exchange? It seemed to Jayavarman that the King went out of his way to hold him up to the household. ‘I give you my trusted right hand, my support in old age, my young and supple Shield of Victory!’ the King cried.

There were groans and protests: no you are not old.

‘I give you my cloud-flower of virtue and respect whose name will join the web of stars overhead!’

He hugged Jayavarman’s shoulders, and leaned on him. The King’s breath smelt of wooden teeth and palm wine. The Little King smiled and thought, this could be dangerous. The King whispered to him, ‘My harrow after death.’

Finally, finally he and his wife were left alone. They walked hand in hand to the household reservoir. It creaked with frogs and crickets. So, the Prince thought, I have a wife as beautiful as the moon, as tuneful as the birds. But I don’t really know her. All our friends surround us.

And from somewhere came grief and he found he was crying.

‘Husband,’ said his new wife. ‘You weep?’

She tried to pull him around. It was not manly to weep. He tried to stop. But suddenly he found he could not stop, and that his legs were giving way under him. He slumped down to the ground. Gracefully, Jayarajadevi lowered herself next to him. ‘My Lord, be happy?’ she chuckled, her voice also unsteady.

‘I don’t know why I do this.’

He looked up at the leaves, stars, moon, and the temple, black and red and gilded, dancing with torchlight.

‘I wish my mother was here,’ he said, locating the grief. ‘I wish my father was alive. I wish I’d been with him when he died.’

‘Ah,’ she said, like wind in the trees. She sat in her gold-embroidered gown on the dry ground. She took him in her arms. ‘It is our fate to lose our families.’

‘I will not see her or my father again. My brothers are taken by the wars. My mother said she did not choose this, that she would always think of me.’

‘She was a very wise and loving mother to say that.’

‘I don’t know why I do this!’ He was so frightened of looking unmanly for his bride.

‘You are weeping because you have come home after such a long time.’ Her own words rocked as if over a bumpy road. She cradled him closer and kissed his forehead. She kissed his closed eyes, for all of their dead. ‘Your father. My father. Your mother.’ She looked into his eyes. ‘What is your name? I don’t know your real name.’

Jayavarman smiled embarrassed and shrugged. He closed his eyes and said his real name. ‘Kráy.’

Jayarajadevi’s face froze.

He said, ‘Kansri, don’t tell anyone, please. It is not a name I can live up to!’ The name in Old Khmer meant Huge, Powerful, Exceeding – Too Much.

Jayarajadevi asked, ‘Your father gave you that name?’

‘No, my mother.’ Jayavarman grinned. ‘She had a vision of me. Mothers do.’

Jayarajadevi Kansri sighed. ‘I won’t ever know your parents.’

‘That’s OK, neither do I.’ He looked smiling, accepting. ‘They were the reverse of what you expect a man and a woman to be. My mother was brave, strong and calculating, but also wilder. She saw things. My father, Dharan Indravarman, was sweet and gentle, always saying look, look at the butterflies. Look at the flowers. Maybe the flowers take wing as butterflies. He cried when animals died.’

His wife took his hand. ‘They sound like exceptional people.’ The tears came again. ‘They were. And I hardly knew them.’

She made him look at her. ‘We will make a new family,’ she promised. ‘We will people that family with children who will honour and respect you. We will build a house of our own, a great house where all our families can come home.’

‘And I will learn about the Buddha. My family were Buddhists. Did you know that?’

She smiled. ‘Everyone knows that, Nia.’ She shook her head. ‘That is why we were matched.’

The Prince bounced up and down. ‘Well. We will build a Buddhist capital! We will make a city of compassion.’ Jayavarman, Victory Shield, clenched his fist. ‘We will make a precious jewel of a kingdom and keep it safe from thieves and hold it up as a shining star to light the rest of the world!’

His wife, his queen, draped herself across him. ‘Yes, my Lord, yes,’ she said. There was a sensation as if they had mounted on the back of a swan. Their world was winging.

Then, Jayavarman went away to war.

April 14, 2004 (#ulink_8395b663-467d-5974-aac8-9b9e1582635e)

The hatch clunks open.

Другие электронные книги автора Geoff Ryman

Lust

0

0