По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

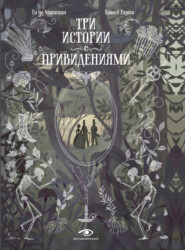

The works of Guy de Maupassant, Volume 5

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Sticking to this idea which now dominated every other.

Renardet exclaimed some distance away:

"You lunch with us, Monsieur l'Abbé – in an hour's time."

The priest turned his head round, and replied:

"With pleasure, Monsieur le Maire. I'll be with you at twelve."

And they all directed their steps towards the house whose gray front and large tower built on the edge of the Brindelle, could be seen through the branches.

The meal lasted a long time. They talked about the crime. Everybody was of the same opinion. It had been committed by some tramp passing there by mere chance while the little girl was bathing.

Then the magistrates returned to Roug, announcing that they would return next day at an early hour. The doctor and the curé went to their respective homes, while Renardet, after a long walk through the meadows, returned to the wood where he remained walking till nightfall with slow steps, his hands behind his back.

He went to bed early, and was still asleep next morning when the examining magistrate entered his room. He rubbed his hands together with a self-satisfied air. He said:

"Ha! ha! You're still sleeping. Well, my dear fellow, we have news this morning."

The Mayor sat up on his bed.

"What, pray?"

"Oh! Something strange. You remember well how the mother yesterday clamored for some memento of her daughter, especially her little cap? Well, on opening her door this morning, she found on the threshold, her child's two little wooden shoes. This proves that the crime was perpetrated by some one from the district, some one who felt pity for her. Besides, the postman, Mederic comes and brings the thimble, the knife and the needle case of the dead girl. So then the man in carrying off the clothes in order to hide them, must have let fall the articles which were in the pocket. As for me, I attach special importance about the wooden shoes, as they indicate a certain moral culture and a faculty for tenderness on the part of the assassin. We will therefore, if I have no objection, pass in review together the principal inhabitants of your district."

The Mayor got up. He rang for hot water to shave with, and said:

"With pleasure, but it will take rather a long time, and we may begin at once."

M. Putoin had sat astride on a chair, thus pursuing even in a room, his mania for horsemanship.

Renardet now covered his chin with a white lather while he looked at himself in the glass; then he sharpened his razor on the strop and went on:

"The principal inhabitant of Carvelin bears the name of Joseph Renardet, Mayor, a rich landowner, a rough man who beats guards and coachmen – "

The examining magistrate burst out laughing:

"That's enough; let us pass on to the next."

"The second in importance is ill. Pelledent, his deputy, a rearer of oxen, an equally rich landowner, a crafty peasant, very sly, very close-fisted on every question of money, but incapable in my opinion, of having perpetrated such a crime."

M. Putoin said:

"Let us pass on."

Then, while continuing to shave and wash himself, Renardet went on with the moral inspection of all the inhabitants of Carvelin. After two hours' discussion, their suspicions were fixed on three individuals who had hitherto borne a shady reputation – a poacher named Cavalle, a fisher for trails and crayfish named Paquet, and a bullsticker named Clovis.

PART II

The search for the perpetrator of the crime lasted all the summer, but he was not discovered. Those who were suspected and those who were arrested easily proved their innocence, and the authorities were compelled to abandon the attempt to capture the criminal.

But this murder seemed to have moved the entire country in a singular fashion. There redisquietude, a vague fear, a sensation of mysterious terror, springing not merely from the impossibility of discovering any trace of the assassin, but also and above all from that strange finding of the wooden shoes in front of La Roqué's door on the day after the crime. The certainty that the murderer had assisted at the investigation, that he was still living in the village without doubt, left a gloomy impression on people's minds, and appeared to brood over the neighborhood like an incessant menace.

The wood besides, had become a dreaded spot, a place to be avoided, and supposed to be haunted.

Formerly, the inhabitants used to come and sit down on the moss at the feet of the huge tall trees, or walk along the water's edge watching the trouts gliding under the green undergrowth. The boys used to play bowls, hide-and-seek and other games in certain places where they had upturned, smoothed out, and leveled the soil, and the girls, in rows of four or five, used to trip along holding one another by the arms, and screaming out with their shrill voices ballads which grated on the ear, and whose false notes disturbed the tranquil air and set the teeth on edge like drops of vinegar. Now nobody went any longer under the wide lofty vault, as if people were afraid of always finding there some corpse lying on the ground.

Autumn arrived, the leaves began to fall. They fell down day and night, descended from the tall trees, round and round whirling to the ground; and the sky could be seen through the bare branches. Sometimes when a gust of wind swept over the tree-tops, the slow, continuous rain suddenly grew heavier, and became a storm with a hoarse roar, which covered the moss with a thick carpet of yellow water that made rather a squashing sound under the feet. And the almost imperceptible murmur, the floating, ceaseless murmur gentle and sad, of this rainfall seemed like a low wail, and those leaves continually falling, seemed like tears, big tears shed by the tall mournful trees which were weeping, as it were, day and night over the close of the year, over the ending of warm dawns and soft twilights, over the ending of hot breezes and bright suns, and also perhaps over the crime which they had seen committed under the shade of their branches, over the girl violated and killed at their feet. They wept in the silence of the desolate empty wood, the abandoned, dreaded wood, where the soul, the childish soul of the dead little girl must be wandering all alone.

The Brindelle, swollen by the storms, rushed on more quickly, yellow and angry, between its dry banks, between two thin, bare willow-hedges.

And here was Renardet suddenly resuming his walks under the trees. Every day, at sunset, he came out of his house decended the front steps slowly, and entered the wood, in a dreamy fashion with his hands in his pockets. For a long time he paced over the damp soft moss, while a legion of rooks, rushing to the spot from all the neighboring haunts in order to rest in the tall summits, unrolled themselves through space, like an immense mourning veil floating in the wind, uttering violent and sinister screams. Sometimes, they rested, dotting with black spots the tangled branches against the red sky, the sky crimsoned with autumn twilights. Then, all of a sudden, they set again, croaking frightfully and trailing once more above the wood the long dark festoon of their flight.

They swooped down at last, on the highest treetops, and gradually their cawings died away while the advancing night mingled their black plumes with the blackness of space.

Renardet was still strolling slowly under the trees; then, when the thick darkness prevented him from walking any longer, he went back to the house, sank all of a heap into his armchair in front of the glowing hearth, stretching towards the fire his damp feet from which for some time under the flames vapor emanated.

Now, one morning, an important bit of news was circulated around the district; the Mayor was getting his wood cut down.

Twenty woodcutters were already at work. They had commenced at the corner nearest to the house, and they worked rapidly in the master's presence.

At first, the loppers climbed up the trunk. Tied to it by a rope collar, they cling round in the beginning with both arms, then, lifting one leg, they strike it hard with a blow of the edge of a steel instrument attached to each foot. The edge penetrates the wood, and remains stuck in it; and the man rises up as if on a step in order to strike with the steel attached to the other foot, and once more supports himself till he lifts his first foot again.

And with every upward movement he raises higher the rope collar which fastens him to the tree. Over his loins, hangs and glitters the steel hatchet. He keeps continually clinging on in an easy fashion like a parasitic creature attacking a giant; he mounts slowly up the immense trunk, embracing it and spurring it in order to decapitate it.

As soon as he reaches the first branches, he stops, detaches from his side the sharp ax, and strikes. He strikes slowly, methodically, cutting the limb close to the trunk, and, all of a sudden, the branch cracks, gives away, bends, tears itself off, and falls down grazing the neighboring trees in its fall. Then, it crashes down on the ground with a great sound of broken wood, and its slighter branches keep quivering for a long time.

The soil was covered with fragments which other men cut in their turn, bound in bundles, and piled in heaps, while the trees which were still left standing seemed like enormous posts, gigantic forms amputated and shorn by the keen steel of the cutting instruments.

And when the lopper had finished his task, he left at the top of the straight slender shaft of the tree the rope collar which he had brought up with him, and afterwards descends again with spurlike prods along the discrowned trunk, which the woodcutters thereupon attacked at the base, striking it with great blows which resounded through all the rest of the wood.

When the foot seemed pierced deeply enough, some men commenced dragging to the accompaniment of a cry in which they joined harmoniously, at the rope attached to the top; and, all of a sudden, the immense mast cracked and tumbled to the earth with the dull sound and shock of a distant cannon-shot.

And each day the wood grew thinner, losing its trees which fell down one by one, as an army loses its soldiers.

Renardet no longer walked up and down. He remained from morning till night, contemplating, motionless, and with his hands behind his back the slow death of his wood. When a tree fell, he placed his foot on it as if it were a corpse. Then he raised his eyes to the next with a kind of secret, calm impatience, as if he had expected, hoped for, something at the end of this massacre.

Meanwhile, they were approaching the place where little Louise Roqué had been found. At length, they came to it one evening, at the hour of twilight.

As it was dark, the sky being overcast, the woodcutters wanted to stop their work, putting off till next day the fall of an enormous beech-tree, but the master objected to this, and insisted that even at this hour they should lop and cut down this giant, which had overshadowed the crime.

When the lopper had laid it bare, had finished its toilets for the guillotine, when the woodcutters were about to sap its base, five men commenced hauling at the rope attached to the top.

The tree resisted; its powerful trunk, although notched up to the middle was as rigid as iron. The workmen, altogether, with a sort of regular jump, strained at the rope, stooping down to the ground, and they gave vent to a cry with throats out of breath, so as to indicate and direct their efforts.

Two woodcutters standing close to the giant, remained with axes in their grip, like two executioners ready to strike once more, and Renardet, motionless, with his hand on the bark, awaited the fall with an uneasy, nervous feeling.

One of the men said to him:

Renardet exclaimed some distance away:

"You lunch with us, Monsieur l'Abbé – in an hour's time."

The priest turned his head round, and replied:

"With pleasure, Monsieur le Maire. I'll be with you at twelve."

And they all directed their steps towards the house whose gray front and large tower built on the edge of the Brindelle, could be seen through the branches.

The meal lasted a long time. They talked about the crime. Everybody was of the same opinion. It had been committed by some tramp passing there by mere chance while the little girl was bathing.

Then the magistrates returned to Roug, announcing that they would return next day at an early hour. The doctor and the curé went to their respective homes, while Renardet, after a long walk through the meadows, returned to the wood where he remained walking till nightfall with slow steps, his hands behind his back.

He went to bed early, and was still asleep next morning when the examining magistrate entered his room. He rubbed his hands together with a self-satisfied air. He said:

"Ha! ha! You're still sleeping. Well, my dear fellow, we have news this morning."

The Mayor sat up on his bed.

"What, pray?"

"Oh! Something strange. You remember well how the mother yesterday clamored for some memento of her daughter, especially her little cap? Well, on opening her door this morning, she found on the threshold, her child's two little wooden shoes. This proves that the crime was perpetrated by some one from the district, some one who felt pity for her. Besides, the postman, Mederic comes and brings the thimble, the knife and the needle case of the dead girl. So then the man in carrying off the clothes in order to hide them, must have let fall the articles which were in the pocket. As for me, I attach special importance about the wooden shoes, as they indicate a certain moral culture and a faculty for tenderness on the part of the assassin. We will therefore, if I have no objection, pass in review together the principal inhabitants of your district."

The Mayor got up. He rang for hot water to shave with, and said:

"With pleasure, but it will take rather a long time, and we may begin at once."

M. Putoin had sat astride on a chair, thus pursuing even in a room, his mania for horsemanship.

Renardet now covered his chin with a white lather while he looked at himself in the glass; then he sharpened his razor on the strop and went on:

"The principal inhabitant of Carvelin bears the name of Joseph Renardet, Mayor, a rich landowner, a rough man who beats guards and coachmen – "

The examining magistrate burst out laughing:

"That's enough; let us pass on to the next."

"The second in importance is ill. Pelledent, his deputy, a rearer of oxen, an equally rich landowner, a crafty peasant, very sly, very close-fisted on every question of money, but incapable in my opinion, of having perpetrated such a crime."

M. Putoin said:

"Let us pass on."

Then, while continuing to shave and wash himself, Renardet went on with the moral inspection of all the inhabitants of Carvelin. After two hours' discussion, their suspicions were fixed on three individuals who had hitherto borne a shady reputation – a poacher named Cavalle, a fisher for trails and crayfish named Paquet, and a bullsticker named Clovis.

PART II

The search for the perpetrator of the crime lasted all the summer, but he was not discovered. Those who were suspected and those who were arrested easily proved their innocence, and the authorities were compelled to abandon the attempt to capture the criminal.

But this murder seemed to have moved the entire country in a singular fashion. There redisquietude, a vague fear, a sensation of mysterious terror, springing not merely from the impossibility of discovering any trace of the assassin, but also and above all from that strange finding of the wooden shoes in front of La Roqué's door on the day after the crime. The certainty that the murderer had assisted at the investigation, that he was still living in the village without doubt, left a gloomy impression on people's minds, and appeared to brood over the neighborhood like an incessant menace.

The wood besides, had become a dreaded spot, a place to be avoided, and supposed to be haunted.

Formerly, the inhabitants used to come and sit down on the moss at the feet of the huge tall trees, or walk along the water's edge watching the trouts gliding under the green undergrowth. The boys used to play bowls, hide-and-seek and other games in certain places where they had upturned, smoothed out, and leveled the soil, and the girls, in rows of four or five, used to trip along holding one another by the arms, and screaming out with their shrill voices ballads which grated on the ear, and whose false notes disturbed the tranquil air and set the teeth on edge like drops of vinegar. Now nobody went any longer under the wide lofty vault, as if people were afraid of always finding there some corpse lying on the ground.

Autumn arrived, the leaves began to fall. They fell down day and night, descended from the tall trees, round and round whirling to the ground; and the sky could be seen through the bare branches. Sometimes when a gust of wind swept over the tree-tops, the slow, continuous rain suddenly grew heavier, and became a storm with a hoarse roar, which covered the moss with a thick carpet of yellow water that made rather a squashing sound under the feet. And the almost imperceptible murmur, the floating, ceaseless murmur gentle and sad, of this rainfall seemed like a low wail, and those leaves continually falling, seemed like tears, big tears shed by the tall mournful trees which were weeping, as it were, day and night over the close of the year, over the ending of warm dawns and soft twilights, over the ending of hot breezes and bright suns, and also perhaps over the crime which they had seen committed under the shade of their branches, over the girl violated and killed at their feet. They wept in the silence of the desolate empty wood, the abandoned, dreaded wood, where the soul, the childish soul of the dead little girl must be wandering all alone.

The Brindelle, swollen by the storms, rushed on more quickly, yellow and angry, between its dry banks, between two thin, bare willow-hedges.

And here was Renardet suddenly resuming his walks under the trees. Every day, at sunset, he came out of his house decended the front steps slowly, and entered the wood, in a dreamy fashion with his hands in his pockets. For a long time he paced over the damp soft moss, while a legion of rooks, rushing to the spot from all the neighboring haunts in order to rest in the tall summits, unrolled themselves through space, like an immense mourning veil floating in the wind, uttering violent and sinister screams. Sometimes, they rested, dotting with black spots the tangled branches against the red sky, the sky crimsoned with autumn twilights. Then, all of a sudden, they set again, croaking frightfully and trailing once more above the wood the long dark festoon of their flight.

They swooped down at last, on the highest treetops, and gradually their cawings died away while the advancing night mingled their black plumes with the blackness of space.

Renardet was still strolling slowly under the trees; then, when the thick darkness prevented him from walking any longer, he went back to the house, sank all of a heap into his armchair in front of the glowing hearth, stretching towards the fire his damp feet from which for some time under the flames vapor emanated.

Now, one morning, an important bit of news was circulated around the district; the Mayor was getting his wood cut down.

Twenty woodcutters were already at work. They had commenced at the corner nearest to the house, and they worked rapidly in the master's presence.

At first, the loppers climbed up the trunk. Tied to it by a rope collar, they cling round in the beginning with both arms, then, lifting one leg, they strike it hard with a blow of the edge of a steel instrument attached to each foot. The edge penetrates the wood, and remains stuck in it; and the man rises up as if on a step in order to strike with the steel attached to the other foot, and once more supports himself till he lifts his first foot again.

And with every upward movement he raises higher the rope collar which fastens him to the tree. Over his loins, hangs and glitters the steel hatchet. He keeps continually clinging on in an easy fashion like a parasitic creature attacking a giant; he mounts slowly up the immense trunk, embracing it and spurring it in order to decapitate it.

As soon as he reaches the first branches, he stops, detaches from his side the sharp ax, and strikes. He strikes slowly, methodically, cutting the limb close to the trunk, and, all of a sudden, the branch cracks, gives away, bends, tears itself off, and falls down grazing the neighboring trees in its fall. Then, it crashes down on the ground with a great sound of broken wood, and its slighter branches keep quivering for a long time.

The soil was covered with fragments which other men cut in their turn, bound in bundles, and piled in heaps, while the trees which were still left standing seemed like enormous posts, gigantic forms amputated and shorn by the keen steel of the cutting instruments.

And when the lopper had finished his task, he left at the top of the straight slender shaft of the tree the rope collar which he had brought up with him, and afterwards descends again with spurlike prods along the discrowned trunk, which the woodcutters thereupon attacked at the base, striking it with great blows which resounded through all the rest of the wood.

When the foot seemed pierced deeply enough, some men commenced dragging to the accompaniment of a cry in which they joined harmoniously, at the rope attached to the top; and, all of a sudden, the immense mast cracked and tumbled to the earth with the dull sound and shock of a distant cannon-shot.

And each day the wood grew thinner, losing its trees which fell down one by one, as an army loses its soldiers.

Renardet no longer walked up and down. He remained from morning till night, contemplating, motionless, and with his hands behind his back the slow death of his wood. When a tree fell, he placed his foot on it as if it were a corpse. Then he raised his eyes to the next with a kind of secret, calm impatience, as if he had expected, hoped for, something at the end of this massacre.

Meanwhile, they were approaching the place where little Louise Roqué had been found. At length, they came to it one evening, at the hour of twilight.

As it was dark, the sky being overcast, the woodcutters wanted to stop their work, putting off till next day the fall of an enormous beech-tree, but the master objected to this, and insisted that even at this hour they should lop and cut down this giant, which had overshadowed the crime.

When the lopper had laid it bare, had finished its toilets for the guillotine, when the woodcutters were about to sap its base, five men commenced hauling at the rope attached to the top.

The tree resisted; its powerful trunk, although notched up to the middle was as rigid as iron. The workmen, altogether, with a sort of regular jump, strained at the rope, stooping down to the ground, and they gave vent to a cry with throats out of breath, so as to indicate and direct their efforts.

Two woodcutters standing close to the giant, remained with axes in their grip, like two executioners ready to strike once more, and Renardet, motionless, with his hand on the bark, awaited the fall with an uneasy, nervous feeling.

One of the men said to him: