По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

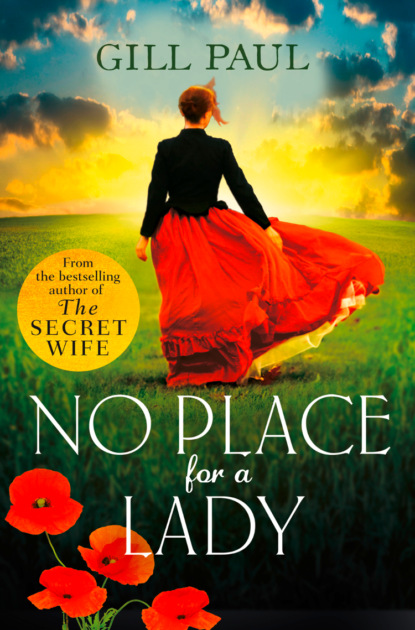

No Place For A Lady: A sweeping wartime romance full of courage and passion

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

But they didn’t, and on 28th March news broke that Britain and France had jointly declared war on Russia in support of the Turks.

Mr Peters was excited: ‘About time,’ he exclaimed. ‘Now we’ll stop those Russians invading their neighbours.’ Dorothea could tell he wished he himself were going to fight, a young man once more.

‘My sister’s husband is a Captain in the 8th Hussars and bound to be sent to fight. She is hoping to accompany him.’ She asked the question that was foremost in her mind: ‘Do you think she will be safe?’

‘Who can say? Wives have accompanied troops to battle for centuries past, and they had their uses in cooking and doing laundry for the men. But times are changing and it’s damn foolishness that they still take them now the new longer-range guns are in use. Commanders’ attention is diverted from the battlefield to providing suitable accommodation for ladies, and extra food is needed. I always thought it was madness.’ He coughed with the effort of this speech. ‘The 8th Hussars, you say? Part of the Light Brigade. Safer than the Heavy Brigade, at least. The Heavies lead the attacks but the Light are mostly used for reconnaissance. Who are your brother-in-law’s family?’

‘The Harvingtons of Northampton.’

‘Are they a military family?’

‘I’m afraid I do not know. I haven’t made their acquaintance.’ Dorothea coloured. ‘I regret to say the marriage was somewhat hasty, arranged so that my sister might go with the army and remain at her husband’s side.’

‘You must be very concerned,’ Mr Peters said in a hoarse whisper.

‘I am.’ Dorothea blinked back a tear. ‘I’m terrified for Lucy but I cannot write to her as I don’t know where they are lodging.’

‘If you write on the envelope “Care of Captain Harvington, 8th Hussars” and send it to the regimental headquarters, they’ll pass it on …’ he rasped, then a tickle caught in his throat and he began to cough with a nasty hacking sound. He closed his eyes as his ribcage heaved with the effort. His lungs often became congested, causing him to choke and struggle for breath but he never complained. Dorothea thumped his back to dislodge the phlegm and held a bowl for him to spit into, noting that his sputum was an unhealthy greenish-yellow in colour. Earlier she’d noticed that his feet were turning black from lack of circulation. She hoped the principal physician would look in on him later.

When the hacking cough had at last subsided, Dorothea saw that Mr Peters’ lips had a bluish tinge and his skin was pale. He seemed to summon every effort to say one more thing to Dorothea. ‘If you’ll excuse me saying, Sister, it’s best to make peace while you still can,’ he whispered, then closed his eyes to rest. Every coughing fit drained his remaining strength.

‘Would you like me to fetch a vicar, or a priest?’ Dorothea asked, wondering if that’s what he was hinting, but he shook his head vehemently. In earlier conversations he had expressed a low opinion of religion but she often found patients changed their minds as death approached.

The physician who came to examine Mr Peters later told Dorothea that he thought the end was near. ‘Can you contact his family?’ he asked.

‘There are no close relatives, I’m afraid. I asked him who I should contact if his condition worsened but he said there was no one.’

Perhaps that will be my situation one day, Dorothea mused – especially if this terrible rift with Lucy is not healed. At thirty-one, she was too old to marry and have children. The thought filled her with sadness, but she comforted herself that at least she had her work. She loved being useful to her patients and knew she was good at easing their suffering and making them feel they were not alone. Hospitals were terrifying places, where you were surrounded by strangers, with doctors whisking in to perform painful procedures before disappearing again. Dorothea tried to make patients feel she was a friend, someone on their side, and their heartfelt thanks were gratifying.

She decided to spend the day sitting with Mr Peters, whose breathing was now tortured and shallow. He clearly didn’t have long to go and she couldn’t let him pass away on his own. She made herself a cup of tea and pulled up a chair by his bed, then wiped his brow and offered him a sip of water but he shook his head. Each breath was an effort and before long he drifted into sleep. There was a rattling in his throat, the noise some called the death rattle, caused, she knew, by saliva gathering once he could no longer swallow. She kept wetting his lips so they didn’t crack and holding a cool cloth on his brow. Although he was unconscious she hoped he could sense her presence.

At four-thirty he opened his eyes one last time, choking from the fluid in his lungs. His hands were freezing cold and she could smell the sharp chemical scent she often noted right at the end. Dorothea slipped the pillow from beneath his head because death would come quicker if he was lying flat. ‘Goodbye,’ she whispered. ‘You are a good man and I’ll miss our conversations.’ She squeezed his shoulder as he took one last virtually undetectable breath, just as she had done five years earlier on the night her mother died.

That had been a cruel death. Her mother had been in hideous pain as the cancer gnawed through her insides. She could keep nothing down, not even the laudanum that could have offered some relief, and her opium enema seemed to do little good. Towards the end the disease had been in her spine, making it impossible to find a comfortable position whether sitting or lying. She was terrified, yet strove to muffle her cries of agony in the blankets so as not to waken thirteen-year-old Lucy, who was asleep in her bedroom down the corridor. Dorothea could see the fear etched in her mother’s eyes, could hear her whispered pleas for help, and was powerless to do more than hold her hand, moisten her lips and soothe her with whispered endearments. The doctor came and went, leaving further useless supplies of laudanum; their vicar came to pray. Her father couldn’t bear it and retreated to his study, leaving Dorothea to witness the final throes of the awful death struggle on her own. It was an experience that scarred her, something that would never leave her. Her mother’s last breath when it came was a blessed release from acute torture and the expression caught at the moment of death was one of horror. Thankfully Lucy had not witnessed any of it. By the time she came to see the body the following morning, their mother’s features had settled into a peaceful repose. Lucy complained of not being called to say goodbye but Dorothea knew she was too young for such a distressing sight.

Mr Peters, by contrast, had a peaceful death, the best he could have hoped for. Dorothea sat with his body for half an hour watching the tightening of his features, the blanching of his complexion, then she helped the orderly to wash and prepare him for the undertaker. It was five-thirty in the evening when she walked out into the street in her dark wool cloak and climbed into a Hansom cab the hospital porter had called to take her back to Russell Square.

Covent Garden was abuzz with costermongers dismantling their fruit and veg stalls under the metal and glass awning, and flower girls with a few remaining pink, white and yellow blooms in their baskets. Some ladies of the night hovered on street corners, hoping for an early piece of business. Nothing shocked Dorothea after her work in the hospital. She had seen all types pass through its doors.

Back in her bedroom, she started to change for dinner but she was too agitated to fiddle with all the buttons on her gown. Instead she sat at her dresser to compose a letter to Lucy. She told her she was sorry for her actions, that she hoped her marriage would be a very happy one. She was sad to have missed the ceremony but perhaps once they were reconciled she could host a celebration for them … Suddenly Dorothea dropped the pen and a great sob tore from her chest. She gasped and tried to control herself but emotion took hold and she shook with intense grief.

‘Please God, don’t let any harm come to Lucy,’ she prayed, squeezing her eyes tight shut. ‘I’ve let her down and I will never forgive myself if anything bad happens to her.’

She laid her head on the dresser and fell asleep, waking an hour later when the bell rang for dinner to find her tears had soaked the writing paper and blurred the ink.

PART TWO (#ulink_bd9738a6-bdf7-5cf3-8247-658aabdf8fe3)

Chapter Four (#ulink_127031ba-e062-5d9a-a2f3-3499794d6dd4)

24th April 1854

Plymouth Dockyard was teeming with people bustling between precarious stacks of luggage. Tall-masted ships stretched as far as the eye could see. The noise of ships’ horns sounding, street traders crying their wares, and the anxious chatter of bystanders was overwhelming. Lucy worried that they would never find their way but when Charlie hailed a porter and asked him to take them to the Shooting Star, the man seemed confident about finding it. He loaded a trolley with their steamer trunk, all their bags stuffed to bursting, and their large tin bath, and set off. Charlie clutched Lucy’s arm tightly and hurried them through the throng in pursuit of their luggage.

Before long, he spotted some comrades in royal blue and gold Hussars uniform and hailed them, pulling Lucy forwards to introduce her. She shook hands with several gentlemen and was pleased to note their appreciative glances. She had dressed with care in a wide-skirted soft wool gown with cascading ruffles in the skirt, and a warm fitted jacket, both of a deep blue very similar to that of the Hussars’ colours. A prettily trimmed bonnet framed her face.

‘I think you have new admirers,’ Charlie winked, squeezing her hand.

As they approached the ship, she noticed several women sobbing, with young children clinging to their skirts, and asked Charlie what ailed them.

‘These are the soldiers’ wives who can’t come along,’ he told her. ‘There was a ballot and only a few won a place. You’re lucky to be the wife of an officer, as we can all bring our wives, if our commanders agree.’

‘What will become of them while their husbands are away?’ She felt alarmed for their plight. She had no idea what would have happened to her if she hadn’t been allowed to accompany Charlie because his wages were not sufficient, after stoppages for uniform and so forth, for him to have supported her in lodgings like the boarding house where they had been living in Warwick for the last three months. She suspected from the haste with which he insisted they leave that he owed money to the landlady there. If a captain couldn’t manage, how could the soldiers, who earned so much less?

‘I expect their families will look after them,’ Charlie said, as if the question hadn’t occurred to him.

Some called out – ‘Miss, can you help us?’ ‘Need a lady’s maid, Miss?’ – and Lucy cast her eyes down, feeling guilty that she had a place while they did not.

They walked up the gangway onto the ship and followed their porter down to the officers’ deck, where Charlie located their cabin. Lucy swallowed her surprise at how small it was, barely six paces wide and ten long, with a bunk so narrow they would be crushed tight together. There was hardly any hanging space for her gowns, and only one tiny mirror above the washbowl.

‘This is one of the better cabins I’ve seen on a military ship,’ Charlie remarked cheerfully. ‘It’s very well appointed.’

Lucy kept her thoughts to herself. ‘I’ll just unpack a few things, dearest, to make it a little more homely.’

‘In that case, I’ll go and check on the horses on the deck below.’ He kissed her full on the lips and grasped one of her breasts with a wink before he left.

Lucy felt her cheeks flush and she hummed as she arranged their possessions. She liked having someone to look after, loved the intimacy of sharing a bed and eating meals with Charlie. ‘You see, Dorothea?’ she thought. ‘You were wrong!’

Before long, she heard women’s voices in the corridor and popped her head out. The first woman she saw introduced herself as Mrs Fanny Duberly, wife of the 8th Hussars’ Quartermaster. She seemed rather superior in attitude, and moved off after only the briefest ‘hallo’ but not before Lucy had noted that her gown was plain grey worsted and not remotely fashionable. The other woman, Adelaide Cresswell, had a kind face and shook Lucy’s hand warmly.

‘Charlie is a good friend of my husband Bill, so you and I must also be friends, my dear.’

‘Yes, please,’ Lucy cried. ‘I would love that. We women must stick together. I need your advice on how I can support my husband. We are so recently wed I don’t yet know what is expected of an officer’s wife.’

Adelaide smiled and squeezed her hand. ‘I was overjoyed to hear about your marriage. Charlie is a very lucky man. Look how pretty you are! Such lovely china blue eyes.’ She glanced past Lucy into their cabin. ‘Goodness, you’ve brought rather a lot of luggage.’

Lucy looked at the pile. ‘In truth, it was hard knowing what to bring. I’ve had to leave many of my possessions in store,’ she explained. ‘Charlie told me I would need summer clothes, but I also tried to think of items we might need if we have to sleep in a tent.’ She couldn’t contemplate quite how she would manage to change her gowns and perform her toilette in such a cramped space but she was prepared to give it a try if that’s what being an army wife entailed. As well as the tin bath, she had brought some soft feather pillows and a pale gold silk bedspread that used to be her mother’s, so they would have some home comforts.

‘Of course you did – and I’m sure they’ll come in very useful. It’s just that we may have to carry our own luggage at times and your trunk looks rather heavy …’ Seeing Lucy’s alarmed expression, Adelaide added quickly: ‘I expect Charlie will find someone to help you. Now, I was on my way below deck to introduce myself to the women travelling with Bill’s company, the 11th Hussars. Perhaps you would like to come and meet the wives of Charlie’s men? There’s plenty of time as the ship won’t leave harbour till after dinner.’

Lucy’s eyes widened. ‘I’d love to!’ It hadn’t occurred to her that Charlie had men beneath him, men who obeyed his commands, but she supposed as a captain that he must. She was anxious to give the right impression and decided she would follow Adelaide’s lead.

Two decks below their own, there was a strong smell of rotting vegetation, which Adelaide told her came from the bilge. The soldiers’ wives were in a shared dormitory and Adelaide greeted them, explaining who she and Lucy were, and saying that they would be happy to offer assistance if any was required. The women looked doubtfully at Lucy, who was by far the youngest of the thirteen wives accompanying the 8th Hussars. Most were rough, sturdy women, with ruddy faces and cheap gowns; none looked a day under thirty.

‘What an exquisite shawl,’ Lucy commented to one woman, who was wearing a gaudy, paisley-patterned garment round her shoulders. ‘Are your beds comfortable? Ours is so narrow I think my husband will knock me to the floor if he turns in his sleep.’

‘Make sure you sleep by the wall so he’s the one that falls out,’ one suggested, and Lucy agreed that would be the sensible course. She asked about children left behind, about where the women normally lived, about their husbands’ names and duties, and she felt by the time she and Adelaide left that she had made a good first impression.

‘We will all be good friends after this adventure. I am sure of it,’ she called back.