По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

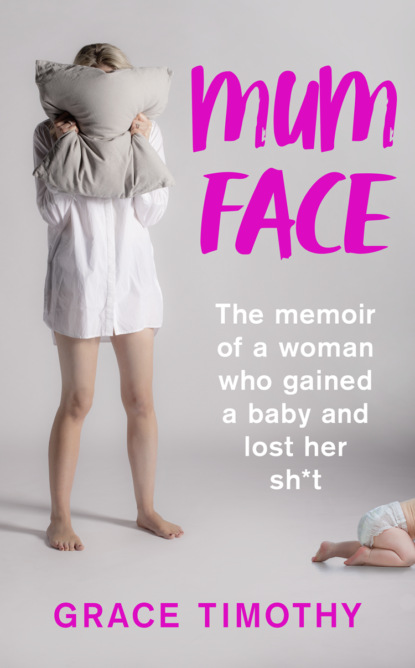

Mum Face: The Memoir of a Woman who Gained a Baby and Lost Her Sh*t

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Being referred to and introduced as ‘Baby’s Mum’ is as reductive as it gets. I mean, I am used to being introduced as something to place me in someone’s mind – so-and-so’s assistant, The Intern, Rich’s wife, Blonde Grace (at uni, I was one of two Graces, Boobs Grace and Blonde Grace) – but being called ‘Mum’ was a bit like being renamed.

I know it sounds like I was worried about losing my cool, but in all honesty, I was never cool. Anyone who mewls, ‘I used to work at Vogue!’ four years after they’ve left and relies on a knock-off designer handbag to help her be taken seriously in her industry isn’t genuinely cool or really that OK with her choices. BUT, I did have a sort of mask of cool perfected. I had some of the right clothes, I had focused on constructing this career that would take me to cool places where I would sweat profusely and wonder if I ever pronounced anything correctly. It was definitely a façade and I’m guessing the imposter syndrome was what was causing my upper lip to be perennially moist. It was a relief to go freelance and only have to maintain over email. But I did believe the last vestiges of anything resembling cool would trickle out of my vagina with the baby. Or, ideally, be delicately lifted from my insides by the surgeon who was performing the C-section I was fantasising about. Because I’d then forever be known as MUM.

And is it any wonder?! When do we fetishise or even celebrate motherhood in our vocabulary? When do we use the words in praise? In fact, my generation have advanced the field by adding the prefix ‘mum’ to things that are really rubbish, to really drive their naffness home. For example, ‘You’re such a mum’ – you nag, you worry, you piss everyone off, you big fat bore. ‘You’re so mumsy’ – you’re dowdy and dumpy and nobody fancies you. ‘Mom jeans’ – the ugliest fucking jeans known to man. They make your vagina look like a big ass and your ass look like a big vagina. FACT. ‘Mommy porn’ – 50 Shades of grammatical errors and submission-based sex. Yuck. I’ll take me some non-parent-related porn, thank you. ‘Mum hair’ – a really crap bob.* (#ulink_2b7f8fac-d155-579e-ba39-a918def09558) ‘Mum face’ – haggard, grey, tired-looking complexion. Probably teary. ‘Yummy Mummy’ – mum who makes a bit of an effort, which for me always had a whiff of the Readers’ Wives about them.

Sometimes ‘mothering’ someone can be kind of nice, but it’s 100 per cent sexless and non-exciting, and tends to be a way of gently pointing out you’re treating someone like a baby. Rather than being fabulous and dazzling, you’re patronising and basically suffocating another person.

So then, mums are tedious, past it and irreparably uncool. You are JUST A MUM. Nothing more than that, even though the ‘just’ suggests you ought to be. I sneered at the idea it would be the hardest job in the world, but fully believed it would be the most boring one. Once we’ve started to make progress on making BITCH and CUNT unacceptable, we’re going to have to explain ‘mum’ isn’t really such a hot diss. It’s just another way of reducing women, of dismissing and degrading them. And it totally worked on me.

Mums are parochial and stuck in the 80s – presumably because that’s where we’ve banished our own mums to. They’re subsumed by domestic drudgery, hoovering in the background of the real narrative, ready to cook or wipe a bum. They are overcome with tiredness and the shame of having no sexual appeal whatsoever. In fact, they have sex only to have more babies, surely?

My mum the wild child

It’s weird that I was so convinced by this depressing idea of motherhood, when my own mum wasn’t really like that. It turns out that although she and my dad had been trying for a baby for a couple of weeks when she got pregnant she still had the same pangs as me, worried about the changes she would be going through. Maybe more so, given that her own parents had split up when she was a child and her mum had never really recovered, dying of a broken heart when she was just 58, all her birds having flown the nest. My mum, in comparison, was a wild child. She didn’t so much dabble in drugs as body-slam herself full force into bags of speed and weed. She had a lot of sex with a lot of people. When she met my dad she was a theatre stage manager, working late into the night, partying hard and sleeping until the matinée started the whole cycle again the next day.

‘What did you do on Sundays?’ I once asked. She couldn’t remember there being any Sundays.

Then she met my Dad. She was in love. So in love that she – the least maternal person ever to walk the earth, she says – married him (even though he had six children) and decided to have a baby.

When she got pregnant her sisters laughed and her dad shook his head gravely. She’d been babysitting my baby cousin for a full 30 minutes when he’d rolled off the bed and cracked his head open on the floor. It was a terrifying prospect. But she quit the fags and coffee, got really fat and eventually bore me into the world.

She wasn’t like the other mums. She didn’t bake or sew or knit. She dyed her hair pink. I never thought of her as ‘mumsy’. She and my dad were considered ‘a bit showbiz’ by my friends’ parents, I think because they had a lot of gay friends and said ‘cunt’ a lot. They threw parties, were out every weekend and she was a force to be reckoned with – a strident feminist and purveyor of crude jokes in a village of doctors and accountants, all of whom voted Tory and sailed every weekend.

She never ‘settled’ in motherhood, she still thought everything could be bigger and better. With her on the PTA the school fete suddenly went from a little jumble sale to a gala for over 3,000 people with celebrity guests, hot-air balloon rides and a remote broadcast from the local radio station.

Mumness

So it was weird that I was really preoccupied with an image of mums cleaning floors and loading the washing machine – great work, advertising industry! Drinking insipid tea in front of daytime television with a worried look on your face. I think I got this from Neighbours or Coronation Street. I was also painfully aware I’d need to learn how to make gravy. That seemed important somehow.† (#ulink_cda487ee-9449-57a2-9951-43465ce2fc1d) ‘MUM’ was the refrain moaned by pre-teen boys in grass-stained football shorts or precocious girls with gappy teeth and pigtails. It was a word always whined or howled in my head.

Of course, it ended up being the most loved sound in my universe – when my kid first mumbled ‘mama’ it was like I’d discovered who I most wanted to be right there. So in the right hands, when it was her saying it, it was the most beautiful sound, like liquid gold. To be fair, she once called me a slut (having heard it on the radio, mind – nothing to do with me) and even that sounded bloody lovely. If I reduce it right down to its fundamental parts, it’s love: motherhood is love. So the name really has bugger-all importance. But back to pregnant me, who had no idea that would be the case.

I wasn’t even on Instagram back then. I didn’t have that group of women saying, ‘Look, you can wear neons and you can get shit pierced and take your kid to gigs! Look at our snazzy backpacks and our gin!’ Without social media, your tribe is whatever you have in front of you. And I was working in an industry where having a baby could end you unless you pretend like it didn’t happen. A baby in a sling was about as likely to win me work as suddenly admitting I had shagged the boss. Actually, less so, because most magazines wouldn’t want me to write about my experience of childbearing.

But then the cold jelly was dolloped onto my stomach, that weird barcode reader was pushed down hard and we heard the swooshing ‘thud-thud-thud’ of a heartbeat. I looked at Rich – Oh my God, are those tears in his eyes?! Is he … is he crying?! – and missed the baby coming into view. When I looked back at the screen it looked like a little puppet. It had the hiccups, according to the sonographer, and we watched as it bounced off its soft bed, limbs flailing like a little Thunderbird. It didn’t look biological at all, it was mechanical and cloudy, like really bad TV.

‘But I can’t feel it,’ I said, completely unable to see this image on the screen as a snapshot of my insides. Not like with a transvaginal scan, where you can feel the probe knocking your ovaries like a piñata. It still wasn’t a baby there on the screen, but it definitely looked like something which might grow into one. Rich was transfixed and I felt bad that I wasn’t bonding with the squiggly little creature that could have been anywhere. It was still sexless in my head, without an identity. But I took the picture they printed and tried to see Rich and I in the image. There was my long chin at any rate, but the long hooked nose looked like a little old man’s. I stared at the picture long and hard to try and see our future – this is our kid, I thought, this is our kid. This is Rich’s kid! I love Rich and this is his child, inside me. This is my very own kid … It didn’t really work, but I’ve never been very good at pep talks.

Then we left and went back to real life, away from this crazy world where we gazed into my belly, and pressed on with the present.

I nearly puke on Anna Wintour

When you’re pregnant you can deal in these diametric opposites quite comfortably as the future is all hypothetical and you can’t imagine not being in control of your own destiny. Moving on from the fear of a baby changing everything, I had resolved that it would change nothing. I don’t want to go to soft play or parks, so I just won’t! I thought, making a mental list of the things I didn’t like about childcare and so would just not indulge. I practised full-scale denial, thanks to the advice of mostly childless people and from reading books by women who had nannies, even though I knew we’d never be able to afford one.

And continuing as if nothing was going to change was actually completely possible during my second trimester, as my energy returned and the sickness calmed down. My belly started growing but the bump was still very much of IBS-bloating proportions and sometimes barely appeared at all. I hadn’t bought a stitch of maternity wear, I was working out the perfect anti-nausea routine in readiness for a return to work, and I was about to prove my theories and capabilities in the most sane way I thought possible: attending Fashion Week. Unfortunately, it would instead be the moment I narrowly missed vomiting on Anna Wintour.

To give you a bit of background information, when I left university I went straight to The Times as a fashion intern. From day 1 at the newspaper, I was hooked. I had a string of badly paid internships and quickly realised that to make the knockbacks and hard graft worthwhile I would need to become fiercely ambitious.

I eventually got a job at Vogue based solely on the fact that my boss at The Times gave me a good reference, and that I spoke Italian (which actually was not true).

Then a job as an actual WRITER came up at Glamour, where I stayed until I’d amassed enough experience to go it alone as a freelance beauty writer. I compiled a list of dream titles I’d try to write for, and at the very top was American Vogue.

So when Style.com – the sister site from the same publisher – asked me to report backstage at London Fashion Week the week I was diagnosed with Hyperemesis Gravidarum, I was like, obviously, yes. At the time they were THE authority on the shows, I’d be mad to turn it down. And if I stepped aside for even one season I’d be quickly replaced by someone who wasn’t inconveniently breeding.

It was just a shame I felt so sick.

I decided to keep my ‘condition’ top secret from those around me.

The first show was at the top of a very high, very glass building, and as I’d over-planned I arrived about an hour early. I stepped out of the elevator, into a vast warehouse-style room, with all the action focused in one corner of rails and pop-up hairdressing stations. I took in the view and as I swayed aboard my ridiculous 4-inch heels, my mouth began to froth. NOT NOW, NOT NOW! I reached for a cracker and scoffed it down like the Cookie Monster, spraying flecks all around me. Then the lift pinged again and out stepped La Wintour. Maker and breaker of careers. Editor-in-chief of the magazine at the top of my wishlist, the doyenne of cut-throat fashion-ism. On any other day, had I not left the top button of my jeans undone and just sprayed water biscuit down my front, I would have approached her. I knew it could be a terrible idea, for sure – she had a brutal way of dismissing people, I’d heard – but her daughter had interned with me at Vogue and I’d met her again on a trip not long after and she was lovely, warm and generous. I had an opener. I wanted it so badly. I wasn’t scared, I was ballsy.

I’ll just go up to her and be all, HEY, ANNA! I know your daughter! Super-casual, just one professional to another. So I straightened my shirt, smoothed my hair down. I got ready to make the ultimate career move.

But instead? I burped. Like, really loudly. Loud enough that the people to the rear of her entourage cloud turned around. I turned around too, as if to ask, WHO WAS THAT?! Then I lurched forward, stumbled backwards, and then hid behind a rail of clothes for the next 40 minutes, dry heaving.

Well, this is new, I thought. Not the dry heaving at work – we’ve all done the morning-after-the-Christmas-party-retch – but the complete lack of control and professionalism in the face of a potentially big career moment. Being pregnant was definitely jamming my work mode and it scared me – what if, no matter how much I try to stay the same, it would actually be impossible? It was so frustrating and terrifying to feel the bit of me that got my mortgage paid and fulfilled my ambitions was under fire.

I managed to write the reports and by staying away from the other beauty editors who would have known what was up when they smelt my acrid breath and the fact that I wasn’t stealing the models’ croissants, nobody was any the wiser. And I decided that once the morning sickness had completely stopped, I’d be able to continue unchanged. The fact is, I’d been in the room with Anna and co., I was still allowed in. I just needed to rein in the impulse to vomit.

We need a new nest

OK, so I was still adamant that nothing had to change. But one thing really did – where we lived. Yes, quite a big thing, actually. The flat that we’d scrimped and saved for, and made our mark on by way of two floating shelves and a new catch on the shower door, had to go. It had been perfect, pre-fertilised-egg – a living room with giant sofas that doubled as a large dormitory for friends to crash out in, and a windowsill over the tub, for stacking candles, books and the occasional bathtime sandwich.

The summer before I’d got up the stick, we decided to put the flat on the market because we thought it might be time to splash out on a garden of our own. Somewhere to drink coffee on a Sunday morning, maybe a box room I could make my office now that I worked from home. It sold at the first viewing (and that shower catch made us £15,000 – snap!) but we couldn’t find anything nice we could actually afford. We dawdled and ummed and ahhed, because we were under zero pressure – so what if the buyer pulls out, we don’t HAVE to move, and we’ll just get another buyer.

But at the end of February, as I entered my eighth week of pregnancy from my mum’s sofa in Chichester, our buyer finally threatened to pull out if we didn’t vacate within four weeks. Rich started to rush over to Brighton after work to check out other flats and back to me in Chichester each evening to endure my rants about his breath. One evening he arrived back from our flat, another bag of my clothes slung over his back, and slumped down next to me on the sofa. I didn’t mention his personal stank because he looked so broken. I’d basically been ignoring him for a month and hadn’t noticed how the commuting and lack of support was getting to him.

‘Look, we need a plan. Nothing new is coming up, we can’t afford anything suitable in Brighton. We have to be realistic.’

Nonononononononono!

‘I think we ought to start looking outside of Brighton. We’ll get more for our money. And I won’t have to commute as far, which means I’ll be back before the baby goes to bed. Brighton is not going to work for us, not right now.’

He’d said it. It was out there. Our life was going to change. But there was a caveat – NOT RIGHT NOW. Once we’d saved a bit of money, maybe we would be able to go back to Brighton, to a proper house. This wasn’t forever, this was for now.

‘And I think the most sensible choice is right here, because I won’t be far from work, you won’t be far from the hospital and your parents will be nearby to help out.’

Fuuuuuuuuuuuuck! I’d no longer be the city girl, living a stone’s throw from her favourite bar, the beach and an ATM machine. I’d be back to where I started, back to bad phone signals, no nightclubs and a lot of fields. Back to socialising with my mum and wider family without having a cool flat and glamorous job to jet back to afterwards. Back to feeling gawky and isolated and frustrated.

‘OK,’ I say, in the tiniest voice, hoping he might not hear and we can just pretend this hasn’t happened. I have no fight in me, and I’m pleased that he seems buoyed by this decision at least. I can deal with the finer details later. At least I wouldn’t have to meet another set of midwives either, or try to navigate a new set of roundabouts, my bête noir as a driver.

My mum was delighted, Rich was grim, and I was escaping it all on Rightmove. It had replaced ASOS as my favourite virtual shopping basket. I was already changing, OH GOD, NO! Ooh, but wait, look, a double garage!

I was supposed to start my job in six weeks’ time, and we would have to have moved before that. And actually, there was a whole bunch of small houses – HOUSES – for the amount of money we’d saved for a one-bed garden flat in Hove. They were mostly new builds – small Tardis houses with boxy rooms and a manicured lawn of fake grass. Then behind door number four was a 122-year-old tiny cottage, with pink roses and a rambling garden full of wild flowers. We both had to duck as we entered and quickly calculated we’d have to ditch both of our sofas. The owners had a baby, so a metre from the main bedroom on a floor that inexplicably sloped and creaked was a tiny box room, barely big enough for a single bed, but already decked out with a cot and shelves of stuffed toys. My mum warned us off it – ‘It’s old! It probably has damp! And what about the sloping floors?!’ – and Rich scraped the skin off his scalp by head-butting the doorframe, but I was in love.

Rich was less keen.

‘There’s no room for our sofas. And what about the floating shelves, where will they go?’

‘It’s bigger than a flat though, isn’t it? And there’s a garden.’