По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

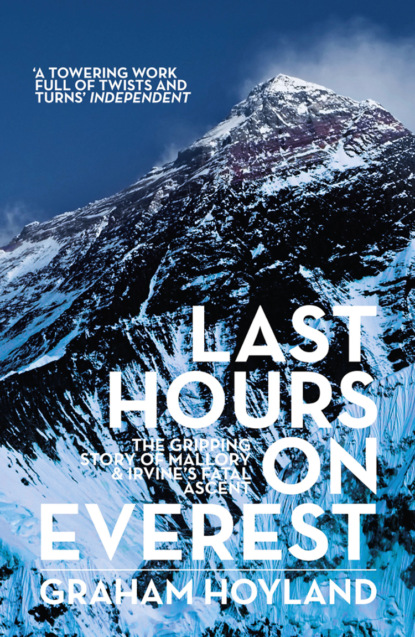

Last Hours on Everest: The gripping story of Mallory and Irvine’s fatal ascent

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

After several more seasons in the Alps, Mallory was considered as one of the best British climbers of his day. His writing style was developing, too, and he made a serious stab at explaining why we climb in a long article in the Climbers’ Club Journal entitled ‘The mountaineer as artist’. He compares a long alpine climb to a symphony, with separate movements for each section of the climb. This might today be considered pretentious, but he makes the point that mountaineering has a spiritual dimension that other sports perhaps lack. It certainly attracts poets and writers. In another piece, written in the trenches, he remembers the joy of reaching the summit of Mont Maudit, and this quotation for me sums up the modest delight of the man:

We’re not exultant; but delighted, joyful; soberly astonished … Have we vanquished an enemy? None but ourselves.5 (#litres_trial_promo)

Just before the outbreak of the First World War he met and married the love of his life, Ruth Turner, the daughter of Hugh Thackeray Turner, a wealthy architect who had worked closely with William Morris, the founder of the Arts and Crafts movement. Their letters reveal that Ruth, although not the clearest of writers, was a wonderful soul-mate, with an unerring ability to get to the nub of things.

In 1910 George had taken a position as a teacher at Charterhouse School in Godalming, Surrey, and attempted to settle down into married life with Ruth. With the outbreak of war, however, he became restless and guilty, feeling that he ought to join up, and obtained a commission as an artillery officer. He was off to war. This was the beginning of many absences from his beloved Ruth, but they wrote to each other nearly every day for the rest of his life.

Mallory survived the war, unlike so many of his climbing peers. Artillery officers had a better chance of survival than ‘the poor bloody infantry’ as they spent less time on the front line, although they were hardly safe. On Mallory’s very first day with his battery, a bullet passed between him and a man walking a yard ahead. On another occasion two men walking with him were killed feet away from him as they laid out a telephone wire.

Of course, if that bullet had swerved a fraction of a degree, the history of Mount Everest would have been different. My father had a torpedo pass right under his ship during the liberation of the Netherlands in the Second World War, and he and his future family were thus inches away from oblivion. Such is the contingency of life, and during dangerous climbing one is well aware that possibilities such as this are multiplying before your eyes. That stone melting out of the ice a thousand feet above you might have your name on it.

Geoffrey Winthrop Young also survived the First World War, although he lost a leg. When he and Mallory organised another of the Pen-y-Pass parties, it was noted that out of 60 climbers mentioned in the diaries from before the war, 23 had died and 14 had been injured.

The more I studied that little band of men in the black and white photographs of the 1921 expedition to Mount Everest, the more I saw the ghosts of the First World War.

Today it is hard to imagine the degree of disconnection between the general public and the soldiers engaged in the slaughter. Now we have live television feeds from journalists embedded on the battlefields, and the death of even one soldier in Afghanistan is headline news. On the first day of the Battle of the Somme in July 1916, however, when Somervell was operating at his field hospital, 19,000 of the British forces were killed: 20 per cent of their total fighting strength. That is over six times the number killed during the 9/11 attacks on the US in 2001, and yet General Sir Douglas Haig, the British commander, felt able to write in his diary the next day: ‘This cannot be considered severe in view of the numbers engaged, and the length of front attacked.’

During the First World War heavy guns were heard in Kent, but successful propaganda duped the British public into believing that all was going well, with the press reporting only light casualties. And the fact that the conflict was so localised and so immovable meant that life could go on in Berlin or London without non-combatants realising what horrors were being perpetrated in their name. One result was that the participants felt disconnected from life at home, even when they returned, and in some cases effectively became walking ghosts.

One such was Mallory’s pupil Robert Graves, who was badly injured by shellfire at the Somme on 20 July while leading his men through the churchyard cemetery of Bazentin-le-Petit. His injuries were so severe that it was reported to his family that he was dead. On his return to London he suffered from hallucinations, seeing the streets filled with corpses. Like many of these veterans he seemed to be slightly lost for the remainder of his life.

What effect might such feelings have on the 26 men in the photographs at Everest Base Camp taken a few years later? And in particular, what consequences might there be on a man making climbing decisions at high altitude?

Most of the members of the 1921 expedition had served in the war and they were being led by a colonel. They saw their attempt to climb the mountain as similar in many respects to warfare, and the whole bandobast of Gurkha soldiers, pack animals and baggage resembled a military expedition. Norton described it as ‘our mimic campaign’, and Mallory wrote in his last Times despatch: ‘We have counted our wounded and know, roughly, how much to strike off the strength of our little army as we plan the next act of battle …’

For Mallory, any notion of warfare as a chivalric enterprise must have swiftly evaporated in 1914 as his former pupils at Charterhouse were shipped off to the trenches: 686 of them would perish in the mechanised slaughter. As we have seen, the reproach of his fireside became intolerable, and he sought some way of joining up, but the headmaster of Charterhouse refused to release him. His university friend the poet Rupert Brooke died in April 1915 in the Aegean on his way to Gallipoli, provoking Mallory to write to Benson: ‘I’ve been too lucky; there’s something indecent, when so many friends have been enduring such horrors, in just going on with one’s job, quite happy and prosperous.’

Eventually the headmaster relented and Mallory joined the Royal Garrison Artillery, a relatively safe billet behind the lines compared with living in the trenches. His ankle injury, suffered in a climbing accident in 1909, was ignored by the medics, but it would become a recurrent problem.

The horrors of the Somme were too terrible to write about to his wife, but in a curious forerunner to Wilfred Owen’s ‘My subject is war, and the pity of war’, Mallory wrote to Ruth: ‘Oh the pity of it, I very often exclaim when I see the dead lying about.’

We have already seen his narrow escapes from bullets and shells. He had a curiously lucky war with his postings, too, and it now appears that he had a guardian angel. Eddie Marsh, Winston Churchill’s private secretary, had interceded to make sure Mallory had ten days’ leave at Christmas 1916, and it is possible that he kept a lookout for him throughout the conflict. Marsh was another of those who had become enamoured of George Mallory – and Rupert Brooke – when, ten years before, he had seen the pair on stage at Cambridge.

One senses an invisible hand guiding events. After his leave Mallory was sent well behind the lines to act as an orderly officer. Then, when he had successfully applied to return to his battery at the front, he was invalided out by the ankle injury the day before the attack at the Battle of Arras. A ‘Blighty wound’ was one that enabled you to be sent back home to Blighty, and one that many soldiers devoutly wished for. After convalescence, Mallory managed to crush his right foot in a motorcycle accident, and missed the Battle of Passchendaele. Then, just before the Spring Offensive of 1918, he was assigned to another training course. In all, he managed to miss nearly a year and a half of the most murderous fighting at the front, even though he had actively sought to put himself in the way of danger by joining up in the first place.

I suspect that Mallory felt a sneaking sense of guilt at surviving the war unscathed while all around him were being killed or maimed. And all because of a slightly embarrassing ankle injury caused by falling off a minor crag, with perhaps a little help with his postings from a well-placed admirer. Could this have fed into a relative lack of concern for his own physical safety high up on the mountain?

A more tangible effect of the war on the first Everest expeditions was that it forced the selection of older men who had done little recent climbing. Sandy Irvine, for instance, was ten years younger than the average age of the other members in 1924. This would have reduced the overall strength of the team, and on his last climb Mallory simply didn’t have a powerful back-up of climbers forcing stores and Sherpas up the mountain behind him.

Mallory’s experiences in the war may have led him to go too carelessly, too impatiently against the greatest enemy he ever faced. His Blighty wound may also have helped his demise, as it was his right ankle that broke once again in his last fall (having saved him in the war, it may have contributed to his death after it). No one can have been very surprised at Mallory and Irvine not returning from their battle with Mount Everest, and in the official history of the 1924 expedition it seemed that Norton had seen it all before:

We were a sad little party; from the first we accepted the loss of our comrades in that rational spirit which all of our generation had learnt in the Great War, and there was never any tendency to a morbid harping on the irrevocable. But the tragedy was very near; our friends’ vacant tents and vacant places at table were a constant reminder to us of what the atmosphere of the camp would have been had things gone differently. To several of us, particularly to those who, on previous expeditions to Mount Everest or Spitzbergen, had been close friends with the missing climbers, the sense of loss was acute and personal, and until the day of our departure a cloud hung over the Base Camp. As so constantly in the war, so here in our mimic campaign Death had taken his toll from the best, for they were indeed a splendid couple.6 (#litres_trial_promo)

5

The Reconnaissance of 1921 (#u06d386a6-a3b9-55cb-b70d-5a5c09aa74c9)

The British Empire was driven by bloody-minded individuals with a sense of mission, such as Livingstone, Napier and Burton, and one such was Francis Younghusband, the man largely responsible for the first attempts to climb Mount Everest.

He was a small, heavily moustached man, who was almost the personification of Empire. He had become the youngest member of the Royal Geographical Society, and in 1890 received the RGS Patron’s Medal for his great journey through Manchuria, undertaken when he was only 23. While on leave from his regiment, he pioneered a route between India and Kashgar, prime Great Game territory. Later, as a captain, he was ordered to survey part of the Hunza valley, where he bumped into his Russian counterpart, Captain Grombchevsky, who was surveying possible invasion routes. After dinner they swilled brandy and vodka, and compared their soldiers. They also discussed the possible outcome of a Russian invasion. After this friendly sparring, straight out of a buddy movie, they rode off in opposite directions.

The threat from Russia was therefore very real, and there was an obvious psychological advantage in gaining the high ground between the two great empires. Lord Curzon, the Viceroy of India, clearly wanted the highest point of the Himalayas climbed, writing that:

As I sat daily in my room, and saw that range of snowy battlements uplifted against the sky, that huge palisade shutting off India from the rest of the world, I felt it should be the business of Englishmen, if of anybody, to reach the summit.

In this context it can be seen that the climbing of Mount Everest was more of a political decision than a ‘wild dream’. In its way it was the British Empire’s moon-shot, with similar political motivation to the United States’ moon-shot of the 1960s. Crucially, it would plant the British flag on the northern bounds of India. The problem was that the Tibetans didn’t want to talk to the British and pursued a policy of splendid isolation, keeping foreigners at an arm’s length. Myths arose about this forbidden land, and the desire to explore it grew.

Then in 1893 Captain Charles Bruce of the Gurkhas, who had climbed with Martin Conway in the Karakorum the previous year, met Younghusband at a polo match. He put the idea of climbing Mount Everest to him and between them they started a train of events that was to prove unstoppable. Younghusband was then Political Officer in Chitral, and the idea fermented within him, particularly as he knew that he could count on the support of the establishment. In the meanwhile Curzon became more anxious about Russian influence in Tibet and decided to do something about it. His chance came when a small group of Tibetans crossed the border and stole some Nepali yaks. This incursion was the excuse for the infamous Diplomatic Mission to Lhasa of 1904, led by Younghusband, who, on his way to Lhasa, saw the mountain at last:

Mount Everest for its size is a singularly shy and retiring mountain. It hides itself away behind other mountains. On the north side, in Tibet … it does indeed stand up proudly and lone, a true monarch among mountains. But it stands in a very sparsely inhabited part of Tibet, and very few people ever go to Tibet.

Younghusband certainly did go to Tibet, and in some style. He was leading a force of British soldiers carrying Maxim machine-guns and cannon. A force of 2,000 Tibetans attempted to resist at Gyantse with matchlock muskets, spears and swords. Their lamas assured them the British bullets would not harm them, but when the smoke cleared over 600 of their number had died. By the time the British reached Lhasa the casualties were nearly 3,000 Tibetans killed, compared with only 40 British soldiers. This was a lesson on the effectiveness of machine-guns as devices for cutting up men, a lesson that was initially ignored by the First World War generals.

Britain gained privileged access to the closed country, and eventually set up telegraph poles all the way to Lhasa. Trading could begin, although some in Europe were sad that one of the last veiled mysteries of geography had been ripped aside so brutally. Curiously enough, the belligerent Younghusband had a mystical experience on his way back from Lhasa and later became a spiritual writer. He saw Mount Everest from one of his camps ‘poised high in heaven as the spotless pinnacle of the world’. In later life he said he regretted his invasion of Tibet.

By Mallory and Somervell’s time the new breed of alpinist was thinking about even higher mountains than those in the Alps and the Caucasus, and were organising the first Himalayan expeditions. However, because both Nepal and Tibet were closed to foreigners Mount Everest seemed an impossible dream. This opinion changed subtly after the geographical poles were reached, and particularly after the tragedy of Scott’s expedition to the South Pole in 1912.

Scott’s endeavour was an example of serious exploration in the old style; that is, exploration with a strong scientific purpose. When his last camp was found it was only 11 miles from the next food dump that might have saved his party. And yet they had man-hauled 30lb of rock samples behind them all the way from the Pole.

There was another example of this serious scientific interest. The palaeobotanist Marie Stopes had applied to join Scott’s second expedition. She had been turned down on the grounds of her sex, but following her advice Scott had looked for a specimen of a coal-forming, fossilised fern named Glossopteris. The discovery of this specimen in the dead explorer’s collection established that Antarctica had once formed part of the first super-continent of Gondwanaland.

In his diary entry for 8 February relating to this discovery near the Beardmore Glacier, Scott writes that they spent ‘the rest of the day geologising … under cliffs of Beacon sandstone, weathering rapidly and carrying veritable coal seams. From the last, Wilson, with his sharp eyes, has picked several plant impressions, the last a piece of coal with beautifully traced leaves in layers, also some excellently preserved impressions of thick stems, showing cellular structure.’

Scott’s last words, written as he lay dying in his own lonely tent, made a powerful impression on me as a schoolboy:

For my own sake I do not regret this journey, which has shown that Englishmen can endure hardships, help one another, and meet death with as great a fortitude as ever in the past. We took risks, we knew we took them; things have come out against us, and therefore we have no cause for complaint, but bow to the will of providence, determined still to do our best to the last … Had we lived, I should have had a tale to tell of the hardihood, endurance, and courage of my companions which would have stirred the heart of every Englishman.

There seems to be something in the English psyche that celebrates the concept of heroic failure. One doesn’t see it in Scottish culture, nor do the Americans have any truck with losers. It is hard to disentangle, but both Scott and Mallory are examples of this phenomenon. Franklin of the North-West Passage is another. I’d suggest it might have to do with the English public schools’ paradoxical injunction to try your very hardest, but not to boast of any success. Bragging is considered one of the cardinal sins. The top winning strategy in this contradictory game is therefore to die heroically trying to reach some impossible goal. I believe heroic failure may have played a small part in Mallory’s psychology, as well as in the minds of his predecessors.

Scott and his party had been beaten by the Norwegian polar explorer Amundsen, who pipped them to the post by employing more effective dog-teams, keeping his attempt secret and treating his expedition as a race. Scott thought it was unsporting to use dogs and insisted on man-hauling the sledges, rather as later explorers thought it would be unsporting to use supplementary oxygen to climb Mount Everest. British moral indignation rose in step with Scott’s elevation to heroic status. ‘Amundsen even ate his dogs!’ they cried. Edward Whymper had referred to Everest as the Third Pole, and this term now gained currency. British pride had to be assuaged, and the ascent of Everest would do as well as anything else.

So, after more years of negotiations and the intervention of the First World War, the Dalai Lama reluctantly gave permission for Mount Everest to be reconnoitred in 1921, with a climbing party to be led by General Bruce the following year. This turn of events was largely thanks to the persistence of Younghusband. By then president of the Royal Geographical Society, he was determined to get an expedition out to the mountain. His 1920 presidential address hints at why people still want to climb Mount Everest:

The accomplishment of such a feat will elevate the human spirit and will give man, especially us geographers, a feeling that we really are getting the upper hand on the earth, and that we are acquiring a true mastery of our surroundings … if man stands on earth’s highest summit, he will have an increased pride and confidence in himself in the ascendancy over matter. This is the incalculable good which the ascent of Mount Everest will confer.1 (#litres_trial_promo)

Before Younghusband’s address the Royal Geographical Society had staged a talk in March 1919 from a truly remarkable Everester. John Baptist Lucius Noel was another one of those privileged soldiers, his father being the second son of the Earl of Gainsborough. Noel was a handsome man and something of an entrepreneur, as later events revealed. I have an interest in Noel because he was the first man to film on Mount Everest, predating my own filming there by some 70 years.

He stood up to read a paper entitled ‘A Journey to Tashirak in Southern Tibet, and the Eastern Approaches to Mount Everest’. Noel described how, when stationed in Calcutta as a lieutenant, he would take his leave in the baking summer months up in the hills to the north, searching for a way to the highest mountain on earth. As with so many of us he became captivated by Everest. Eventually he crossed the Choten Nyi-ma La, a high pass in Sikkim to the north of Kangchenjunga (I saw this pass in 2009, which is now heavily guarded on both sides by soldiers from China and India). Unseen, Noel slipped across, disguised as an Indian Muslim trader:

To defeat observation I intended to avoid the villages and settled parts generally, to carry our food, and to keep to those more desolate stretches where only an occasional shepherd was to be seen. My men were not startlingly different from the Tibetans, and if I darkened my skin and my hair I could pass, not as a native – my colour and shape of my eyes would prevent that – but as a Mohammedan from India.2 (#litres_trial_promo)

His plan was to find the passes that led to Mount Everest and, if possible, to come to close quarters with the mountain. Unfortunately, as I too saw in 2009, there is a difficult tangle of high country between that north-west corner of Sikkim and Everest, and Noel could not get closer than forty miles before he was intercepted and turned back. But it was the closest any Westerner had been, and Noel would play a key part in the 1922 and 1924 expeditions.

His lecture stirred up public debate about the possibility of climbing the mountain, which of course it was intended to do. After many years of wheeling and dealing, of encouragement from Lord Curzon and obstruction by Lord Morley, the Secretary of State for India, an expedition was mounted.

As a result, the 1921 Everest reconnaissance was highly political. The leader was the posh Lt Col Charles Howard-Bury, wealthy and well connected. He was just the man for the job. He moved easily in high diplomatic circles, and proved his worth in helping to secure permission for a reconnaissance in 1921 and a climbing attempt in 1922. He had a most colourful life, growing up in a haunted gothic castle at Charleville in County Offaly, Ireland, travelling into Tibet without permission in 1905, and being taken prisoner during the First World War. He was a keen naturalist and plant hunter (Primula buryana is named after him), and he was the first European to report the existence of the yeti. He never married and during the Second World War he met Rex Beaumont, a young actor with whom he shared the rest of his life. Mallory didn’t care for his high Tory views, nor for the way he treated his subordinates, but Howard-Bury got a difficult political job done, then led the expedition off the map.

The Mount Everest Committee, a joint committee of the Royal Geographical Society and the Alpine Club whose purpose was to fund and organise the reconnaissance, chose the team members on the basis that they had to be able to provide a thorough survey of the massif and give a good assessment of the climbing possibilities. The committee was run by Arthur Robert Hinks.