По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

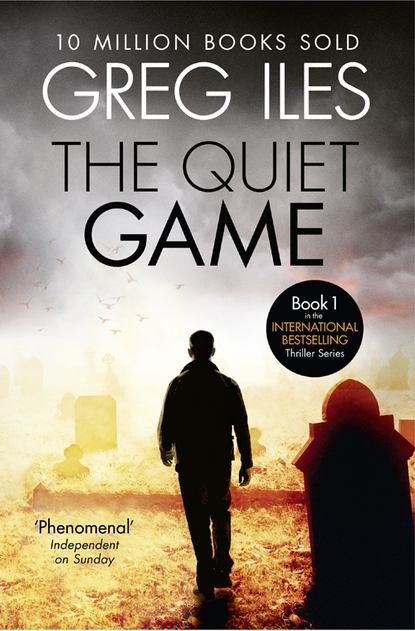

The Quiet Game

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

She actually laughs at this. “I’d just given a seminar to a group of editors in Atlanta. My father was there, and I try to be a bit more conventional when he’s around.”

I can see her point. Not many fathers would approve of the blouse she’s wearing today.

“Look,” she says, “I could have had that story on the wire an hour after you told it to me. I didn’t tell a soul. What better proof of trustworthiness could anyone give you?”

“Maybe you’re saving it for one big article.”

“You don’t have to tell me anything you don’t want to. In fact, we could just eat lunch, and you can decide if you want to do the interview another time or not.”

Her candid manner strikes a chord in me. Perhaps she’s manipulating me, but I don’t think so. “We came to do an interview. Let’s do it. The airplane thing threw me, that’s all.”

“Me too,” she says with a smile. “I liked Annie, by the way.”

“Thanks. She liked you too.”

As we step into the main dining space of the restaurant, a smattering of applause starts, then fills the room. I look around to see whose birthday it is, then realize that the applause is for me. A little celebrity goes a long way in Mississippi. I recognize familiar faces in the crowd. Some belong to guys I went to school with, now carrying twenty or thirty extra pounds—as I did until Sarah’s illness—others to friends of my parents or simply well-wishers. I smile awkwardly and give a little wave to cover the room.

“I told you,” says Caitlin. “There’s a lot of interest.”

“It’ll wear off. As soon as they realize I’m the same guy who left, they’ll be yawning in my face.”

When we arrive at our table, she stands stiffly behind her chair, her eyes twinkling with humor. “You’re not going to pull my chair out for me?”

“You didn’t look the type.”

She laughs and takes her seat. “I wasn’t before I got here. Pampering corrupts you fast.”

While we study the menus, a collection of classic Cajun dishes, I try to fathom how Caitlin Masters wound up in the job she has. The Examiner has always been a conservative paper, owned when I was a boy by a family which printed nothing that reflected negatively upon city worthies. Later it was sold to a family-owned newspaper chain which continued the tradition of offending as few citizens as possible, especially those who bought advertising space. In Natchez the gossip mills have always been a lot more accurate than anything you could find in the Examiner. Caitlin seems an improbable match, to say the least.

She closes her menu and smiles engagingly. “I’m younger than you thought I’d be, aren’t I?”

“A little,” I reply, trying not to look at her chest. In Mississippi, wearing a blouse that sheer without a bra is practically a request to be arrested.

“My father owns the chain. I’m doing a tour of duty down here to learn the ropes.”

“Ah.” One mystery cleared up.

“Okay if we go on the record now?”

“You have a tape recorder?”

“I never use them.”

I take out a Sony microcassette recorder borrowed from my father. “The bitter fruit of experience.”

Our waitress appears and takes our orders (crawfish beignets and iced tea for us both), then stands awkwardly beside the table as though waiting for something. She looks about twenty and, though not quite in Caitlin Masters’s league, is quite lovely. Where Masters is angles and light, the waitress is round and brown and sultry, with the guarded look of the Cajun in her eyes.

“Yes?” Caitlin says, looking up at her.

“Um, I was wondering if Mr. Cage would sign a book for me.”

“Sure,” I tell her. “Do you have one with you?”

“Well—I live over the restaurant.” Her voice is hesitant and terribly self-conscious. “Just temporarily, you know. I have all your books up there.”

“Really? I’d be glad to sign them for you.”

“Thanks a lot. Um, I’ll get your iced tea now.”

As she walks away, Caitlin gives me a wry smile. “What does a few years of that do for your ego?”

“Water off a duck’s back. Let’s start.”

She gives me a look that says, Yeah, right, then picks up her notebook. “So, are you here for a visit, or is this something more permanent?”

“I honestly have no idea. Call it a visit.”

“You’ve obviously been living a life of emotional extremes this past year. Your last book riding high on the best-seller list, your wife dying. How—”

“That subject’s off limits,” I say curtly, feeling a door slam somewhere in my soul.

“I’m sorry.” Her eyes narrow like those of a surgeon judging the pain of a probe. “I didn’t mean to upset you.”

“Wait a minute. You asked on the plane if my wife was traveling with me. Did you know then that she was dead?”

Caitlin looks at the table. “I knew your wife had died. I didn’t know how recently. I saw the ring …” She folds her hands on the table, then looks up, her eyes vulnerable. “I didn’t ask that question as a reporter. I asked it as a woman. If that makes me a terrible person, I apologize.”

I find myself more intrigued than angered by this confession. This woman asked about my wife to try to read how badly I miss her by my reaction. And I believe she asked out of her own curiosity, not for a story. “I’m not sure what that makes you. Are you going to focus on that sort of thing in your article?”

“Absolutely not.”

“Let’s go on, then.”

“What made you stop practicing law and take up writing novels? The Hanratty case?”

I navigate this part of the interview on autopilot, probably learning more about Caitlin Masters than she learns about me. I guessed right about her education: Radcliffe as an undergrad, Columbia School of Journalism for her master’s. Top of the line, all the way. She is well read and articulate, but her questions reveal that she knows next to nothing about the modern South. Like most transplants to Natchez, she is an outsider and always will be. It’s a shame she holds a job that needs an insider’s perspective. The lunch crowd thins as we talk, and our waitress gives such excellent service that our concentration never wavers. By the time we finish our crawfish, the restaurant is nearly empty and a busboy is setting the tables for dinner.

“Where did you get your ideas about the South?” I ask gently.

At last Caitlin adjusts the lapels of her black silk jacket, covering the shadowy edge of aureole that has been visible throughout lunch. “I was born in Virginia,” she says with a hint of defensiveness. “My parents divorced when I was five, though. Mother got custody and spirited me back to Massachusetts. For the next twelve years, all I heard about the South was her trashing it.”

“So the first chance you got, you headed south to see for yourself whether we were the cloven-hoofed, misogynistic degenerates your mother warned you about.”

“Something like that.”

“And?”

“I’m reserving my judgment.”