По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

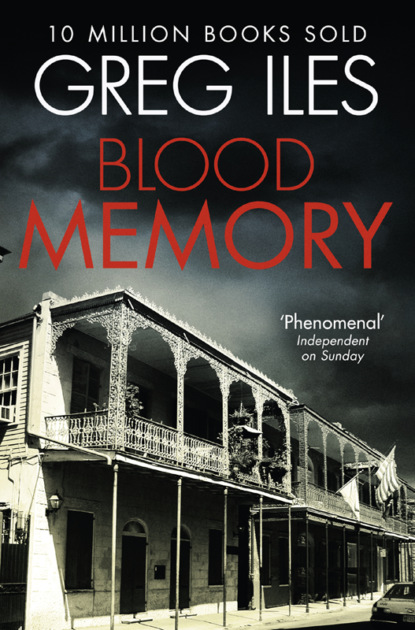

Blood Memory

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“I’m home now, Cat. Where are you?”

“Swimming at the Hemmeters’ house.”

“That’s not the Hemmeters’ house anymore.”

“I know. I just met Dr. Wells.”

“Did you? Well, get home and tell me what’s going on.”

I hang up and look at Michael. “I need to get out.”

He retrieves a towel from his back porch, hands it to me, then turns away. Walking quickly up the pool steps, I strip off my underwear and dry my skin. Then I put on my outer clothes and wring out my bra and panties to carry home.

“All covered up again.”

Michael turns around. “Please feel free to use the pool anytime.”

“Thanks. I won’t be in town long, though.”

“That’s too bad. Do you …” As question fades into silence, color rises into his cheeks.

“What?”

“Do you have someone in New Orleans?”

I start to lie, then decide honesty is best. “I really don’t know.”

He seems to mull this over, then nods with apparent contentment.

I turn to go, but something makes me turn back to him. “Michael, do you ever have patients who just stop speaking?”

“Stop speaking altogether? Sure. But all my patients are kids.”

“That’s why I asked. What causes a child to stop speaking?”

He bites his bottom lip. “Sometimes they’ve been embarrassed by a parent. Other times it’s anger. We call it voluntary mutism.”

“What about shock?”

“Shock? Sure. And trauma. That’s not voluntary, in the strictest sense.”

“Have you ever seen it last for a year?”

He thinks about it. “No. Why?”

“After my father was shot, I stopped speaking for a year.”

He studies me in silence for several moments. There’s a deep compassion in his eyes. “Did you see anyone about it?”

“Not as a child, no.”

“Not even a family doctor?”

“No. My grandfather was a doctor, you know? Mom said he kept telling her the problem would be self-limiting. Look, I need to run. I hope I see you again sometime.”

“I do, too.”

I walk backward for a few steps, give Michael a last smile, then turn and sprint off through the woods. When I am deep into the trees, I stop and look back.

He’s still staring after me.

TEN (#ulink_4835c3de-45cb-5daa-8daf-58b2a21cc38a)

My mother is waiting in the kitchen of the slave quarters, sitting at the heart-pine breakfast table. She’s dressed impeccably in a tailored pants suit, but she has dark bags under her eyes, and her auburn hair looks as though she drove all the way from the Gulf Coast with her windows down. She looks older than when I last saw her—a brief lunch in New Orleans four months ago. Still, Gwen Ferry looks closer to forty than fifty-two, which is her true age. Her elder sister, Ann, once had the same gift, but by fifty Ann’s troubled life had stolen the lingering bloom of youth. At one time the two sisters were Natchez royalty, the beautiful teenage daughters of one of the richest men in town. Now only my mother carries what’s left of that banner, occupying the social pinnacle of the town: president of the Garden Club, a deceptively courteous organization that once wielded more power than the mayor and the board of aldermen combined. She also owns and operates an interior design center called Maison DeSalle, which caters to the small coterie of wealthy families that remain in Natchez.

She stands and gives me a side hug, then says, “What in the world is going on? I’ve always asked you to come home more often, and now you show up without even a phone call.”

“Glad to see you, too, Mom.”

Her face wrinkles in displeasure. “Pearlie says you found bloody tracks in your bedroom.”

“That’s right.”

She looks perplexed. “I went in there and didn’t find a thing on the floor. Just a bad smell.”

“You went into my room?”

“Why wouldn’t I?”

The coffeemaker bubbles on the counter, and the aroma of Canal Street coffee hits me. Trying to suppress my exasperation, I say, “I’d appreciate you not going in there anymore. Not until I’m finished.”

“Finished with what?”

“Testing the rest of the bedroom for blood.”

Mom interlocks her fingers on the table, as though trying to keep from fidgeting. “What are you talking about, Catherine?”

“I think I’m talking about the night Daddy died.”

Two splotches of red appear high on her cheeks. “What?”

“I think those footprints were made on the night Daddy died.”

“Well, that’s just crazy.” She’s shaking her head, but her eyes have an unfocused look.

“Is it, Mom? How do you know?”

“Because I know what happened that night.”