По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

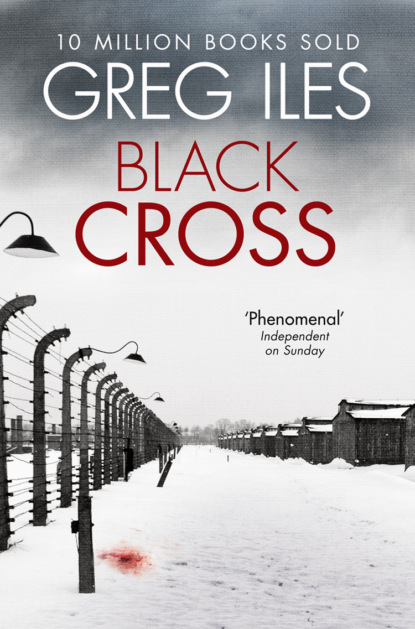

Black Cross

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Brigadier Smith glanced at the young Zionist one last time. “So far, you haven’t shown much of a talent for that.”

Stern showed his right palm to the brigadier and wiggled his middle finger up and down, the most obscene Arab gesture he knew.

NINE (#ulink_2f0a4c44-206f-5ce7-af98-d6f868c161e4)

In Oxford it was raining. McConnell stood inside a bewildering maze of metal pipes, pressurized storage tanks, rubber hosing and racks of gas masks—a maze of his own construction. There were enough skull-and-crossbones POISON signs tacked around the lab to scare off a German regiment. Two elderly white-coated assistants worked quietly at the far end of the lab, preparing for the afternoon’s experiment.

McConnell leaned against a window and looked down into the sandstone courtyard three floors below. Cold rain pooled in the cracks between the stones, running through channels carved over the past six centuries. He wondered if his brother was flying today. Did weather like this ground B-17s? Or was David navigating the sunny ether above the clouds, humming a swing tune while he pressed on towards Germany with death stowed under him?

Hardly a day had passed since their last meeting that Mark had not gone over his brother’s words again. His determination not to participate in the race for a doomsday gas remained as strong as it had been that night, yet something within him would not let the issue rest. How many scientists had faced similar dilemmas during the war? Certainly those on the Tube Alloys project, men who labored in the shadowy, Faustian field of atomic physics. They had much in common with the men working in the sealed chemical laboratories at Porton Down. Good men living in bad times. Good men making compromises, or being compromised. How could he explain why he couldn’t help them?

He watched the raindrops spatter on the window glass, wiggle like bacteria on a slide, then coalesce and run down, seemingly without direction, to join the water collecting in the gutter pipe, a liquid momentum with force enough to wear away the stone below. He thought of what David had said in the Welsh Pony, about the American boys gathering for the invasion. A rain of young men falling on England, out of airplanes, spilling out of the holds of ships, coalescing into groups that formed the cells of a colossal human wave. An incipient wave that grew each day, leaning eastward, that would soon be poised for a great leap across the Channel. It would leap as a whole, but it would break on the opposite shore and shatter into its component parts, individuals, young men who would water the ground with their blood.

That cataclysmic event, though still in the future, was already as unstoppable as the setting of the sun. The men behind it had come together in England, and around themselves were drawing young lives by the millions. They breathed the scent of history, and across the Channel perceived nothing less than the Armies of Darkness, Festung Europa, the fortress of the Antichrist, waiting to receive their mighty thrust.

But something else awaited them there. McConnell had seen it for himself, and heard it. He had traveled across the Channel to Belgium, and to France, and walked the fields that had once been crisscrossed with trenches and mud. He had stood awhile above the intermingled regiments of bones resting fitfully in shallow graves beneath the soil. And there, in whispers just beneath the wind that howled across the stark terrain, he had heard the puzzled voices of boys who had never known the inside of a woman, who never had children, who had never grown old. Seven million voices asking in unison the unanswered question that was an answer in itself:

Why?

Very soon those boys would have company.

“You okay, Doctor Mac?”

Startled, Mark turned from the window and saw his assistants holding four small white rats beside the hermetically sealed glass chamber he called the Bubble.

“Fine, Bill,” he said. “Let’s get to it.”

The Bubble stood nearly five feet high, not tall enough for a man to stand in, but plenty of room for a small primate. Rubber hoses of various gauges snaked across the floor from storage cylinders to fittings in the Bubble’s base. Inside the chamber lay four round, variously colored objects about the size of English footballs. One by one, the assistants picked up the containers, opened small hatches in their sides, and stuffed the rats inside. One rat per football. When the containers were sealed, the assistants rolled them back into the Bubble and secured its main hatch. McConnell was reaching for the valve on a gas cylinder when someone knocked on the lab door.

“Come,” he said.

Brigadier Duff Smith strode into the lab, an enthusiastic smile on his face. He carried a few extra pounds around his middle, the inevitable toll of middle-age, but the muscle beneath was fit and hard. The second man through the door stood over six feet tall, and his skin had the burnished tan of a desert dweller. His dark eyes focused on McConnell and stayed there.

The brigadier surveyed the array of equipment. “How goes it, Doctor? What are we up to today? Bringing the dead back to life?”

“Quite probably the reverse,” McConnell said sourly. He reached down and opened the valve. The muffled hiss of gas released under pressure sounded in the room.

Smith glanced at the glass chamber. “What’s in the Bubble today? Rhesus monkeys?” He craned his neck. “I don’t see anything.”

“Look closer.”

“Those four footballs?”

“That’s exactly what we call them. Inside each of those footballs is a rat. The surfaces are made of mask filter material.”

“For what class of gases?”

“Blue Cross. That’s hydrocyanic acid going in now. If you feel the slightest irritation in your nasal passages, hold your breath and run like hell. The gas is odorless and nonirritant, so I’ve added a small amount of cyanogen chloride to let us know we’re about to die.”

“How long do we have to get clear after we smell it?”

“About six seconds.”

Brigadier Smith’s dark companion stiffened. Smith grinned and said, “Plenty of time, eh, Stern?”

McConnell shut off the valve. “That should be enough to tell. Go ahead and clear it.”

An assistant started a noisy vacuum pump.

“Your friends at Porton Down think the Germans have given up on this gas, Brigadier,” McConnell said over the rattle. “I don’t. It’s difficult to build up a lethal concentration on the battlefield, but that’s just the kind of challenge the Germans love. Hydrocyanic acid can kill you in fifteen seconds if it saturates your mask filter. We call that ‘breaking’ the filter. Our current filters are easily broken by hydrocyanic acid, and I think the Germans know that. I’m trying to develop virtually unbreakable filter inserts for the M-2 through M-5 series canisters.”

“Any success so far?”

“Let’s take a look.” McConnell signaled an assistant to shut off the pump, then donned a heavy black gas mask and motioned for Smith and his companion to move back against the wall. The Bubble gave off a sucking sound as he opened its door. He lifted one of the footballs, held it at arm’s length, opened its hatch and stuck two fingers through the aperture. Brigadier Smith watched, fascinated, as McConnell drew the white rat from the football by its pink tail.

The rodent hung motionless in space.

“Damn!” McConnell said, pulling off his mask. He turned and watched his assistants pull dead rats from the other three footballs. He shook his head in frustration. “Dead rats. That’s my life for the last three months.”

“I don’t see any obvious signs of suffocation,” Brigadier Smith observed.

McConnell took a scalpel from a soapstone table and neatly sliced the rat’s throat. Then he squeezed its body to express arterial blood. “See that? The blood is cherry red, as if it were fully oxygenated. Cyanide attaches to the hemoglobin molecule in place of oxygen. A soldier will look like he’s in the bloom of health while he’s suffocating.”

While the assistants disposed of the rodents, Smith leaned closer. “I’d like to speak to you in private, Doctor. How about the Mitre Inn? We could take a room.”

“I’d prefer to talk here.” McConnell glanced over Smith’s shoulder at the silent stranger, then called to his assistants, “We’ll start back up after dinner.”

When the assistants had gone, Smith pulled up a chair and straddled it, resting his right arm on its back. The gesture emphasized his missing limb. “We’ve had some more disturbing news,” he said. “Out of Germany.”

“I’m all ears.”

“First, if you don’t mind, I’d like you to bring Mr. Stern here up to speed on the chemical warfare situation. He’s a Jew, originally from Germany. Fresh in from Palestine, if you can believe it. Gas isn’t his line. Just a brief overview. German nomenclature, if you please.”

“You’ve read the classification manual.”

“But you helped write it,” Smith said patiently. “I like my information from the horse’s mouth.”

McConnell directed his answer to Stern. “Four classes, designated by colored crosses. You just saw Blue Cross in action. White Cross is tear gas. Green Cross denotes chlorine, phosgene, diphosgene, et cetera. They’re the oldest chemical weapons, but still first-rank battlefield choices. They kill by causing pulmonary edema—internal drowning. The last is Yellow Cross, which also dates back to World War One.” McConnell wiped his brow and spoke in a mechanical voice. “Yellow Cross denotes the ‘blister’ gases, or vesicants. Mustard … Lewisite. Highly persistent gases. Wherever they touch the body, they produce burns, blisters, and deep ulcers of the most painful kind. The body’s ability to heal is impaired, making the effects of Yellow Cross especially long lasting.”

“Thank you,” Smith said. “But you left out a class, I believe.”

McConnell’s eyes narrowed. “The last class has no cross classification,” he said carefully.

“As of yesterday it does. Black Cross.”

“Schwarzes Kreuz,” McConnell said softly. “A fitting name for a tool of the devil.”

“Come now, Doctor. If I didn’t know you were a scientist, I’d swear you were superstitious.”