По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

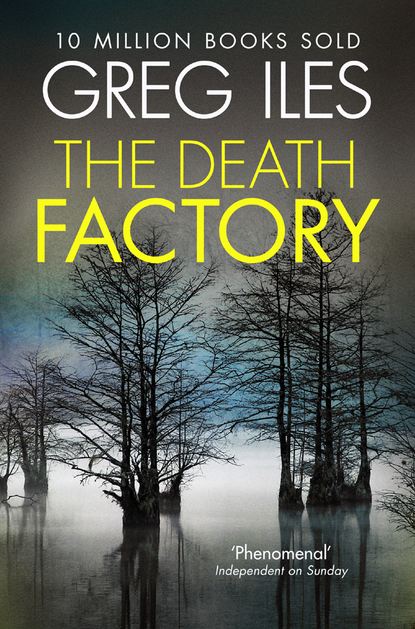

The Death Factory: A Penn Cage Novella

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“Smells like cigars,” Jack says with a smile. “Every car he ever had smelled like this.”

“I hope this one always does.”

The heavy doors close with a satisfying thunk.

“Tom loves this car,” Jack says. “He says it reminds him of his time serving in Germany.”

I back out of the parking space and pull up to Jefferson Davis Boulevard. “Where do you want to go?”

“Why don’t we go to a drive-through and get some coffee, then take a drive? I haven’t been to Natchez in six years, and that was just for Christmas. I must have seen a hundred downed trees during my ride in from the airport. Big oaks.”

“Katrina hit us pretty hard, even up here. Some families were without power for a week.”

“I’d like to see that gambling boat that nearly sank. Or that you nearly sank. Is it still down under the bluff?”

“No. They’ve towed it to a refitting yard in New Orleans for repairs. I hear the company’s going to sell it, and the new owners may reopen in three or four months. Can’t let a cash cow sit idle.”

“I’d like to see the river, anyway,” Jack says. “Being near something of that scale has a way of putting problems into perspective.”

“The river it is.”

St. Catherine’s Hospital stands on high ground about two miles inland from the Mississippi River. I turn north on Highway 61, then pull into a McDonald’s drive-through lane and order two coffees, and a chicken sandwich for Jack.

“What’s happening in California?” I ask, making conversation.

“Same as it ever was, ever was, ever was.”

“And Frances?” This question carries some weight; Jack’s wife was diagnosed with lupus eight years ago.

“She’s doing as well as can be expected. Up and down, you know. She lives for the grandkids now. Jack Junior just extended his fellowship at Stanford, so we see him a lot. And Julia just moved from Sun to a start-up you haven’t heard of yet.”

“But will soon, I suppose?”

Jack laughs. “From your lips to God’s ears.”

As the line of cars inches forward in fits and starts, Jack taps his fingers on the dash. “You know,” he says, “there’s something I’ve always wanted to ask you.”

“What’s that?”

“Why have you stayed in Natchez? I mean, I understand why you came back. Your wife’s death, right? And your daughter having trouble with it?”

“That was most of it. More than half.” I hesitate, wondering whether today is the day to delve into darker chapters of the past. But the idea that my father might be hiding something makes me think of another mentor who threw my lifelong opinion of him into doubt. “But there was more to leaving Houston than that.”

“More than Sarah’s death? And your daughter?”

I hesitate a final moment, then plunge ahead. “Yes. Something strange happened just before Sarah died. She only lived four months after the diagnosis, you know. And right near the end, this other thing came out of nowhere. It knocked the cork out of something that had been building in me for a long time, while I was working as a prosecutor. I just didn’t know it. After I resigned from the office to focus on writing, I repressed it. I thought I’d put all that behind me. But I hadn’t.”

“Does this have to do with you shooting that skinhead guy? Arthur Lee Hanratty?”

That name triggers a silent explosion of images behind my eyes: a pale face leering in the dark, a bundled baby blanket clutched in one arm below it, the other reaching for the handle of our French doors in the moonlight shining through them—

“It was Joe Lee Hanratty I shot,” I say softly. “Arthur Lee was executed in 1998.”

“Oh.”

“No. This was something else.”

Jack nods thoughtfully. “Your death penalty cases?”

“How did you know?”

“I sensed a change in you over the years you worked that job. I could tell you were glad to get out of it. I’ve been surprised that you haven’t written about it, though. Not as a central focus, anyway.”

“Not honestly, you mean.”

Jack shrugs. “It’s your life, man. I’d like to hear about it, but I understand if you’d rather not go there.”

An awkward silence fills the car. Thankfully, the SUV ahead of us moves, and the McDonald’s server passes me the coffee and a white bag. One minute later I’m turning off Highway 61 onto 84, heading west toward the river while Jack munches on his chicken sandwich.

The road that leads toward downtown Natchez cuts through old plantation lands still verdant with foliage in late October. Where slaves once walked, a foursome of black golfers in bright caps and polo shirts putt white balls across a manicured green. Behind them the sun falls on oak and elm trees hardly dotted with autumn browns, but heavy with Spanish moss. When we reach the intersection with Homochitto Street, I turn right, into town, and soon we’re passing Dunleith, the antebellum mansion that I always say makes Tara from Gone with the Wind look like a woodshed.

“Why haven’t you bought that yet?” Jack asks, elbowing me in the side.

“You couldn’t pay me to take on that kind of headache. Besides, a friend owns it, and even he spends most of his time out of town. It’s tough living in a house people fly to every weekend to get married.” As I brake for the red light at Martin Luther King, I say, “I’ve actually been thinking about writing about what happened in Houston. But that would upset a lot of people. Maybe damage some careers. It’s erupted into a major scandal over the past year, and it’s going to get worse.”

“Now I’m really interested. You said this happened near the time of Sarah’s death? How long before she got sick had you resigned from the DA’s office? A while, right?”

“Three years. I left shortly after I killed Hanratty. That experience scared Sarah so bad that she simply couldn’t handle me staying in the job.”

“So whatever it was took three years to come to a head?”

“If it had been left to me, I probably would have buried it for life. But then someone came walking out of the past, almost like a messenger. And he was bearing in his hands the very thing I thought I’d escaped.”

“That sounds ominous.”

“It was.”

The light changes, and I head into the center of old Natchez, where the doors of the police cars once proclaimed WHERE THE OLD SOUTH STILL LIVES—and not so long ago. I turn left on Washington Street, where my town house stands, then drive slowly toward the river between the lines of crape myrtles drooping over parked cars.

“When I took the assistant DA job in Houston, I was one year out of UT law school. Sarah and I had gotten married my senior year. I was pro–capital punishment, always had been. And in a world of perfect cops, lawyers, crime labs, and juries, I still would be. But Harris County tries more capital cases than any other in the nation. It also sends more people to death row, and they don’t linger there for decades. They get executed. I saw that sausage grinder from the inside, Jack. Unlike in the rest of America, the death penalty system in Houston pretty much works as the law intended. Mainly because it’s adequately funded. We had enough courts and judges to handle the caseload—or a good part of it—and we could afford to pay visiting judges, experts to testify, and order complex forensic analyses. That streamlined the process, made it practicable. Then you have the Texas ethos that’s persisted from the frontier days. ‘West of the Pecos justice,’ they call it. If somebody stole a horse or shot somebody in the back, they hung him. You can bet the gangbangers who evacuated New Orleans during Katrina aren’t finding Texas to their liking.”

Jack says, “I’ve heard Harris County called ‘the Death Factory’ on talk radio in California.”

“They call it that all over the country, and not without reason. Harris County sends more people to death row than the other forty-nine states combined.”

“Jesus, Penn.”

“I know. I spent most of my time working for the Special Crimes Unit, prosecuting complex cases like criminal conspiracies, serving on joint task forces, that kind of thing. But I also handled a certain number of capital murder cases. It’s like a rite of passage in that office, and I did my share. And I don’t mind telling you, I had no problem with it. Because when you deal with the victims, as we did, it’s hard to see any flaw in capital punishment. I studied the brutalized corpses, examined crime scenes, hugged distraught parents and siblings—some of whom never recovered from losing their loved ones in that way. I heard audio and saw video recordings that killers had made of their crimes. And in every death case I prosecuted, I realized that there was a moment in which the killer had coldly made a decision to take his victim’s life. The rapist who strangled a girl after raping her, then stomped on her throat to be sure she was dead. The robber who shot terrified cashiers and clerks who had obeyed every order given to them. The skinheads who chained a guy to a bumper and dragged him over gravel until he was in pieces. When you see that . . . it’s hard to see justice in any sentence but death.”