По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

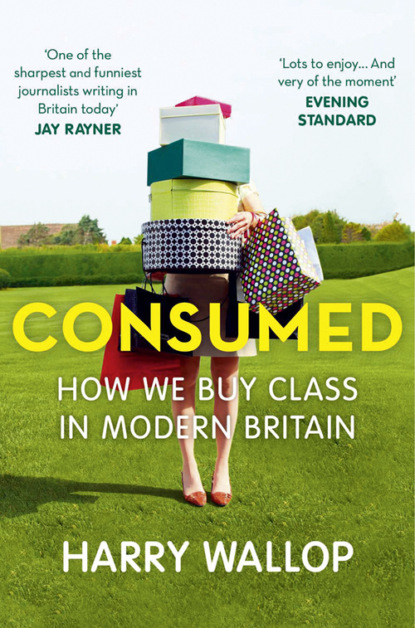

Consumed: How We Buy Class in Modern Britain

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

I am aware that a book on class, which ignores the old pillars of social status – family, education, work – is one that only tells half the story, so I have attempted to tackle these topics as well, though even here, I argue, consumption plays a significant part in determining status. There are not many children that made it to Oxford whose parents never spent a penny on a tutor, music class or educational trip out.

It is all these consumer decisions that help separate the ‘middle classes’ that somehow include the Duchess of Cambridge – in her Le Chameau green wellies, Zara tops and Boden skirts – from the ‘middle classes’ that include Asda Mums, living off tinned food just before pay day. With a dazzlingly varied array of shops, brands and products available to furnish our lifestyles, there are many different types of middle class. This book attempts to categorise these different middle classes along patterns of consumption and explain why some brands remain exclusive and desired and others succumb to ‘prole drift’, why Iceland is despised by so many while Aldi is worshipped, why holidaying in Norfolk in a tent is so much more high class than in a hotel in Florida. For ease of reference I have given all these groups labels, many of them a bit flippant. Despite the stereotypes, we are not as a nation easily split into discrete groups, and I realise many of the labels are far from perfect.

There are the Portland Privateers, high earners and high spenders, who stamp their status (often newly won) onto their children before they have even been born by booking into the private maternity unit, preferably the Portland Hospital in London. They are some of the key supporters of a number of successful high-end, high-visibility brands that have flourished even in the economic downturn: Mulberry, Belstaff, Smythson. To the untrained eye they may appear similar to the Rockabillies. This lot is a broad church of consumers, but they have very much a rural attitude to life, even if they live in Fulham rather than Fairford. They are often wealthy individuals, sometimes not at all, whose defining feature is holidaying at home, ideally at the resort of Rock in Cornwall, where they can mingle with fellow Prosecco-sipping holidaymakers in their Jack Wills hoodies and Boden swimming trunks, red trousers, whipping up a Jamie Oliver recipe on the barbecue.

Similar in attitude to the Portland Privateers, but a million miles away from them in terms of income, are the Hyphen-Leighs – acutely aware of the power of brands and labels and keen to assert their status through spending. Their ability to latch onto the latest fashions and make them their own stretches even to the naming of their children – invariably double barrelled and unusually spelt. Paul’s Boutique and Sports Direct are their natural high street habitats, places where smart casual takes on a whole new meaning.

Sun Skittlers couldn’t really give two hoots about whether their polo shirt has a penguin in a top hat, a crocodile, a polo player or a hippo in a bath on the front. Money is spent on leisure, not fashion – from a 40p copy of the Sun to a game of skittles down at their local working men’s club. None of them defines themselves as middle class, but they are fully paid up members of the modern consumer class who despite fairly low incomes are usually home owners, sun seekers and season ticket holders.

The Middleton classes, named in honour of Carole, rather than Catherine, started off life in almost an identical situation to the Sun Skittlers, but have spent many of their waking hours escaping from their red-top, blue-collar, hire-purchase background. They too embraced all the opportunities that consumer Britain threw at them but they wanted more; and trips to Torremolinos were upgraded to Tuscany, the Daily Herald was swapped for the Daily Mail, the Co-op meat counter for M&S ready meals. This does not make them traitors to their roots; they are the golden generation that helped drive post-war Britain out of austerity and are proud to declare themselves ‘middle class’.

Asda Mums, mostly on low incomes, shy away from defining themselves as middle class. But their subtle understanding of status and brands, their insistence that their babies are given organic Ella’s Kitchen mango pouches (while the older one gets a McDonald’s as a treat), their championing of Pampers and Thorpe Park, prove that so much of modern consumption is driven by parents buying for their children. No more so than with this group.

Then there are the Wood Burning Stovers, the descendants of the original Habitat-shopping generation. A well-turned garlic press and a wood-burning stove, rather than an electric whisk and a large TV, is what gives them pleasure – you can spot them with their Daunt book bags tripping their way to pick up a box of yellow courgettes from their farmers’ market in their Birkenstock sandals, trying not to look too smug.

These groups are introduced throughout the book, and will I hope shed a little light on the country we are. Of course many people straddle more than one group and throughout their life have travelled through different classes. I am already on about my third class, having strived to squash my pheasant-plucking background ever since I was at school. I now fall mostly within the Wood Burning Stover category, which is not something I feel particularly comfortable with. No one likes to be pigeon-holed; we all understandably believe that our consumption patterns are unique. But, as the book explains, the consumer companies that supply us with our food, drink, leisure and clothes spend a considerable amount of time categorising us. We might as well try to beat them at their own game.

There are a small number of consumers who claim, with some legitimacy, to be entirely outside the consumer society – to never shop at a supermarket, to never fly abroad and to take great pleasure in shredding the Argos catalogue onto their compost heap. But these too are defined just as much by their opposition to the branded, consumer world as those who shop at JD Sports. And you’ll find a fair few of them happily scouring the John Lewis kitchen department or their local car boot fair and picking up a cut-price smoked salmon at Aldi.

Crucially, I hope to explain why this ability to define ourselves through what we buy or don’t buy is partly out of our control. Many of our choices have already been ‘edited’ by the shop, the restaurant, the food manufacturer, the holiday company. Sir Terence Conran – one of the towering figures in the rise of the consumer classes – was always very firm in refuting the idea that he ‘instructed’ people how to live their lives, that his restaurants and shops somehow imposed on us a manual for middle-class living. But though he was never as crass as to tell people that the only route to happiness was sipping an espresso or snuggling under a duvet, his ‘philosophy’ was choice editing. ‘I want to show people things they may not have seen before. After all, people can only buy what they are offered and what I want to do is offer them things in as honest and genuine way as I can manage; offer things that people may not have known they might want.’

Over the last two generations one of the triumphs of capitalism has been consumer companies’ ability to anticipate what their customers wanted, or thought they wanted, and provide it for them. They have done this through relentless analysis of their customers, where they live, what they buy, when they shop. Supermarkets have been at the forefront of this trend, but others have learnt to be just as adept and spend millions of pounds every year to refine their marketing, their choice of stock and where they site shops. Often what you put into your basket or which outlet you visit is determined not by you, but by the company, many of whom have worked out exactly who they want through their doors. And who they don’t.

I too have tried to mine the data and find out more about these different middle classes – and indeed about those that are still outside the 70 per cent. From toffs to chavs, from posh wankers to gyppos. The class system still throws up terms of abuse with a vitriol that would be unacceptable when describing race, sex or age. Working class is only occasionally heard as a straight description; it is usually as a nostalgic badge of honour worn by those who have made it to the House of Lords. Instead we have the underclass, the benefits spongers, the feckless, the scroungers. What’s left of the upper classes, too, come in for an equally rough ride. Posh, public-school toffs are to be laughed at, in their ‘Look at my fucking red trousers’ and appearances in the pages of Tatler. The middle classes, in becoming ever wider, have pushed those outside of its ranks to the margin, so far away from normal life as to be comic-book creations fit only for ‘scripted reality’ shows.

Although this book is mostly concerned with products, shops and brands, it is really about people, all of them in some way members of the modern British consumer classes. Class does not reside in products, it only takes shape in ownership of those things or rejection of them. I hope their stories, and my story too, will explain a little bit about where we have ended up in Britain today.

CHAPTER 1

FOOD (#ufbdc2ae3-c675-5cbb-b0ba-32a2c48ddca8)

How did something as innocent as a lunchtime sandwich or morning coffee become the cause of social anxiety? Here we meet the Asda Mums.

The ready meal was nothing new in 1979. TV dinners were in existence before the advent of colour television, and Fray Bentos pies had long been available to consumers unwilling or unable to take the time to cook their own evening meal.

But in 1979, the year Margaret Thatcher swept to power promising to bring harmony to the discordant classes, the ready meal went upmarket, thanks to Cathy Chapman, then 24-year-old head of poultry development at Marks & Spencer. She had already enjoyed success thanks to the simple, though radical for the time, idea of removing first the skin from a chicken breast, and then the bone from a thigh. The following year the breast became coated in Japanese breadcrumbs – crunchier, denser breadcrumbs than a home cook could ever produce from a stale piece of sliced white. Her next product, however, took it to another level.

It was the chicken Kiev. Now, for some, an object of derision, as naff as a tie-dye shirt or snowball cocktail, then, a sophisticated bistro dish that had been appearing on the menus of London restaurants for a few years. It was the first ‘middle-class’ ready meal and helped pave the way for the produce we see on our supermarket shelves today: everything from cheese and ham chicken Kievs from Iceland (£1 for 2) to Charlie Bigham’s Moroccan chicken tagine from Waitrose (£5.99). The ready meal industry is now worth £1.22 billion every year and is at the front line of a never-ending class war over food. Mealtimes have always been fraught, but over the last generation as our diets have become ever more varied, exotic and full of choices, the opportunities to feel bad about what you have put on your plate have been been greater than ever.

Back in 1979, when most people probably thought a Moroccan tagine was something you either smoked or sat on, high-quality cuisine meant French cuisine. Chapman lived in Islington, north London, just 400 yards from Robert Carrier, a restaurant in Camden Passage named after its owner, by then a television star, best-selling cookery writer, innovator of the wipe-clean recipe cards, and proud owner of two Michelin stars. In 1975 the restaurant had hosted dinner for the Queen Mother and Lord Grimthorpe, the first time Her Majesty had dined out in a public restaurant since before her marriage in 1923.

Chapman was encouraged by her bosses at M&S to eat at the best restaurants, and it was at Carrier that she first tried chicken Kiev.

‘Yes, I liked it. What’s not to like? Butter, garlic and a crisp outside,’ she recalls. Her taste of crispy, buttery heaven coincided with the rise of an entrepreneur called John Docker, ‘who believed this kind of food – chicken Kiev, prawn cocktail, duck à l’orange – could and should be available to a wider audience,’ explains Chapman. He set up a factory and staffed it with professional chefs who would then sell their pre-prepared meals for restaurants to re-heat. But he had ambitions for families at home also to enjoy this sophistication. And when he showed the dish to M&S, Chapman and her team decided Britain was ready for the first-ever chilled ready meal.

This is what made it different. It was not a boil-in-the-bag meal that you bought from the freezer cabinet, or a dismal pie in a tin. This was a dish presented in an aluminium tray, in the chiller cabinet of a supermarket, still a relatively small area dedicated to dairy products. It was protected by a cardboard box, with a glossy photograph on the front, and sold for £1.99 – the equivalent of about £8 in today’s money, a premium price for a premium product. They even, in the early days, came with a little paper chef’s hat on the sprig bone that protruded from the meat to make it look worthy of a magazine photo shoot. ‘It was really upmarket, fresh prepared food, the first time we’d done restaurant quality meals. It was a very big launch.’ This was food for the middle classes, and the upper middle classes at that.

Like all big launches for M&S it had to be approved by the board of directors. At this point the Kiev was nearly torpedoed. ‘My boss at the time, the head of food, said when he tasted it, “It’s got garlic in. I don’t like garlic, people don’t like garlic” – and said it shouldn’t be put on the shelves.’ This was not an uncommon view at the time. But with six weeks to go before launch it was too late to back out. With all the boxes printed, Chapman was forced to persuade the director he was wrong, and a Kiev without garlic was pointless.

She was right. It was an immediate hit. The dish was the height of sophistication, with its very name evoking exotic, Cold War Russia (Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy was one of television’s hits of 1979), while the oozing, melting, garlicky butter hinted at a continental elegance that most people in winter-of-discontent Britain could only dream of. The first weekend, £10,000-worth was sold, and they ran out; production was immediately doubled. Within four weeks this one dish was bringing £50,000 a week into the M&S tills. ‘The sales were phenomenal and it became a talking point at the time. People would have dinner parties and serve it, saying, “Here’s one I made earlier,” and it wasn’t; it was one they’d bought at the end of the road.’ To this day, Marks & Spencer, despite its food sales being one-tenth the size of Tesco, sells more chilled ready meals than any other retailer in Britain

and its dine-in-for-£10 meal deal during the recent recession was the salvation for many Portland Privateers and Middleton class people who had been forced to cut back on eating out at their local restaurant.

M&S’s timing was impeccable and Chapman’s persistence was prescient. Ever since Tetley introduced the tea bag in 1953, convenience food had been growing more sophisticated, but it had never really won over either gourmets or the upper middle classes, the customers that had helped M&S become Britain’s biggest clothing retailer. There was always a fear that processed food was either a bit gimmicky, or frankly just a little common, especially when it was frozen or dehydrated. Fresh ready meals that could be passed off as restaurant-quality dishes you had magically whipped up in your kitchen were a salvation for a generation of women, who were now out during the day working, and didn’t have the time to slave over a stove as their mothers had done.

But though the Kiev was a hit, and helped encourage all the other supermarkets to launch chilled ready meals – in turn fuelling their amazing success at grabbing more of consumers’ disposable income – it exposed class divides when it came to eating, divides that are now deeper than ever before. Greggs versus Pret à Manger, McDonald’s versus Wagamama, frozen chicken dippers versus sous-vide smoked duck. Something as innocent as a slice of white bread may have had the salt content reduced, but it has never been so loaded with social anxieties. It used to be about whether you asked Norman to phone for the fish knives, and whether you called it tea, supper or dinner (or even ‘country supper’ if you are in the Chipping Norton set). Those old-fashioned distinctions about terminology and cutlery still exist to some extent, but the deeper divides are about what you put in your mouth and sip from your morning cup.

Some people not only turn down but actively despise certain meals because they are ‘for chavs and idiots’ and refuse to step inside particular food shops. Food writers are both worshipped – Delia, Jamie, Nigella all so famous they go by first names only – but also reviled for promoting an unobtainable, Wood Burning Stover lifestyle, where the windowsill always has fresh basil, the sausages are always organic and the olive oil is always Fair Trade, and preferably Palestinian too.

Indeed, one’s supermarket of choice has now become almost a short-hand for what socio-economic group you belong to – are you an Asda Mum or Tescopoly drone? A Waitrose deli-counter devotee, an Aldi acolyte or a member of the Farmfoods underclass? Which one are you?

It was all so different back in 1954, when food rationing finally ended with the lifting of meat restrictions. Ration books were burnt in celebration and Smithfield market opened at midnight for the first time since before the war. It had been a slow process allowing Britons unfettered access to food. Indeed, food rationing had been in place for nearly half of the period between 1954 and the end of the First World War.

In an age when sushi is so ubiquitous that Marks & Spencer sells enough seaweed to wrap around the M25 every year

it is hard to imagine quite how dismal the diet of most families was. As the 1950s were about to start, the weekly ration for a man was 13 ounces of meat, 8 ounces of sugar, 6 ounces of butter or margarine, 2 pints of milk, 1.5 ounces of cheese, 1 ounce of cooking fat and 1 egg.

It was just not possible to have a food revolution on those provisions. Or even a particularly tasty meal. Of course the rich, as always, enjoyed some immunity because they could afford to eat in restaurants, which were free from rationing – though certain limitations were in place, such as meat and fish not being allowed to be served at the same sitting.

Even when eating out, however, the options were limited. Before the war, most food eaten out of the home was consumed, if not in a work canteen, either in a fish and chip shop, a tea room or department store café at one end of the scale, or in an intimidating hotel restaurant at the other end. Outside London, the idea of a reasonably priced, unpretentious restaurant where a working-class family could enjoy a meal was almost unheard of. The most popular option was Lyons corner houses, a chain that had dominated the eating-out market for decades, which made a fortune for its founders, the Jewish immigrant Salmon family (Nigella Lawson is one of the heiresses). Hot meals were served, and some were waitress service, but it was hardly sophisticated fare.

The first (1951) edition of The Good Food Guide, produced by an army of amateur reviewers (a full half-century before TripAdvisor), lays bare quite how uncosmopolitan the British restaurant scene was. Of the 484 restaurants and pubs reviewed outside London, only 11 served primarily foreign food, and of those ten were European, with just one Chinese included.

The idea of the guide came from Raymond Postgate, who had been a founding member of the British Communist party. Though by the 1950s he had put aside Marxism, he took a militant approach to eating out. He believed that diners had a duty to approach their Dover soles or brandy snaps with a certain hostility if they were to ensure they were not to be diddled by the owners of the means of production. ‘On sitting down at the table polish the cutlery and glasses with your napkin. Don’t do this ostentatiously or with an annoyed expression, do it casually. You wish to give the impression not that you are angry with this particular restaurant, but that you are suspicious, after a lifetime of suffering.’ He deserves credit just as much as Elizabeth David, the ground-breaking food writer, for freeing the British from brown meat and browner sauces.

The old hotel dining rooms were crucibles of class. Intimidating, and so often depressing, they were a test for most families eating out. Cutlery, china, wine lists and waiters – all were traps to trip you up and make you feel a fool. My father-in-law can remember clearly the tension in the house as his own father prepared to go off on a trip down from their home town, Workington, to London to represent his union at a dinner. The dinner was to be a formal one at a big West End hotel. So, his father was sat down at the ‘best kitchen’ table (what most working-class people would have called the parlour) and given a tutorial by his wife about the arcane rules of fish knives, soup spoons and which glass to touch first. She had been in service and knew the pitfalls and was determined that he wouldn’t let the side down.

As a family they never ate out, except for when they went on a trip to the department store in Carlisle or Newcastle. ‘Department stores had quite nice restaurants in those days. The prices in Binns [now owned by House of Fraser] were quite reasonable. We’d have fish and chips or a pie, nothing spectacular. Certainly no coffee.

‘But we would never have eaten out in Workington. There was a chap called Walter Archer, who had a bakery and confectionery business, who opened a café in one of his shops, which survived no more than a year or so. He told us that the trouble with the people of Workington is that the moment they’re within five miles of home they don’t see the point of eating out. He was right.’ And if a café or tea room was considered a wasteful luxury, the restaurant at one of the town’s two hotels was out of the question.

The playwright Alan Bennett, a butcher’s son who won a scholarship to Oxford, recalls the horror of his parents visiting him at university and the trip to the hotel. The waiter came with the menu. ‘Mam would say the dread words, “Do you do a poached egg on toast?” and we’d slink from the dining room, the only family in England not to have its dinner at night.’ They were also befuddled by the wine list. But then, as Bennett asks plaintively, ‘What kind of wine goes with spaghetti on toast?’

This partly explains why Britain, more than any other country outside America, was to embrace fast food. It offered the promise of being classless. No waiters, no wine list, no pretentious French terms, no embarrassment about the bill. The first in Britain, opening the year that food rationing ended, was Wimpy. Within a few years it was already starting to change the face of Britain’s high streets and diets, as the Observer reported at the end of the decade: ‘Dirty and lethargic cafés with fly-blown sandwiches and antique sausage rolls have given way to mechanised eating places, though the staff have not always kept pace with jet-age eating.’

Each table came with a wipe-clean menu and the Wimpy signature condiment: a ketchup bottle in the form of a plastic, squeezy tomato; and burgers cost just one shilling and sixpence, the equivalent of a cinema ticket or three loaves of bread – more expensive than it is now in relative terms, but considerably cheaper than a café meal.

The concept, American of course, was brought to Britain by Lyons. In 1958, 5.5 million burgers were sold, enough for one in ten of the population to have eaten a Wimpy that year. What was their success? the newspaper asked. ‘For the customer, particularly the all-important teenager, they are quick, simple and classless. A Wimpy can be eaten in less than ten minutes, leaving the rest of a lunch hour for shop gazing, flirting or jazz.’ Sadly, the nearest today’s office workers get to flirting and jazz at lunchtime is a quick trawl on Facebook.

‘The Wimpy bars, with their bright layout and glass fronts, are inviting and casual, with none of the inhibiting air of posher places. In contrast to the working-class egg-and-chip cafés or middle-class ABCs [Aerated Bread Company tea rooms] the Wimpy bars have the same kind of American class neutrality as TV or Espresso bars.’

Of course eating out in fast food places, or indeed any places, never became a classless activity. As with so many exciting, new, American activities that hit Britain in this period – pop music, jeans, frozen fish – classless merely became a euphemism for working class. No more so than with fast food, which over time took on a demonic quality, at least in the eyes of those who refused to eat it. Junk food for the junk classes.

This demonisation was mostly peddled by the Wood Burning Stovers, who as time went on were more than happy to have someone else cook their meal in bistros, trattorie and pho noodle bars – but not if it was ‘mechanised’, nor if it was American. McDonald’s, by the sheer force of being successful and American, became the whipping boy. By the mid-1980s, a decade after it arrived in Britain, it was expanding fast, rapidly taking market share from Wimpy and Wendy’s, another chain, and the company wanted to open an outlet in Hampstead, invariably described in tabloid newspapers as ‘leafy’. It is a particularly charming borough of north London, whose heath has majestic views down to the City and Westminster. Home of Keats, Sidney Webb, D.H. Lawrence and Edith Sitwell, it was, in its own estimation, a cut above McDonald’s. There proceeded an almighty 12-year-long row that ended up in the High Court.

‘The last rampart has fallen,’ The Times declared in 1992 when the burger chain finally won the right to open – on the site, symbolically, of a disused bookshop. Everyone quietly forgot that prior to that it had been occupied by a branch of Woolworths. The Hampstead residents, led by local MP Glenda Jackson, the only elected member of parliament to have won an Oscar, and author Margaret Drabble, insisted they were neither being snobs nor prejudiced against burger bars, they just didn’t like the idea of extra traffic and litter. The Heath and Old Hampstead Society said the result would be a rash of copy-cat chains, low-grade boutiques instead of proper shops ‘where one could buy a reel of cotton’.

The true feelings of residents, however, were revealed in a letter to Camden Council, which complained about an influx of ‘noisy undesirables’, while the actor Tom Conti said, ‘McDonald’s is sensationally ugly.’ As the Washington Post rather neatly put it, Hampstead was not so much a village, more a rather smug state of mind. The residents of Hampstead always have been Wood Burning Stovers to a man, Radio 4 devotees, owners of Ottolenghi cookbooks, recipients of organic food boxes. They sip flat white coffees from their local Ginger & White café (slogan: ‘We don’t do Grandes’), which offer organic marmite and soldiers for toddlers who have learnt to order a babycino before they can wipe their own nose.