По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

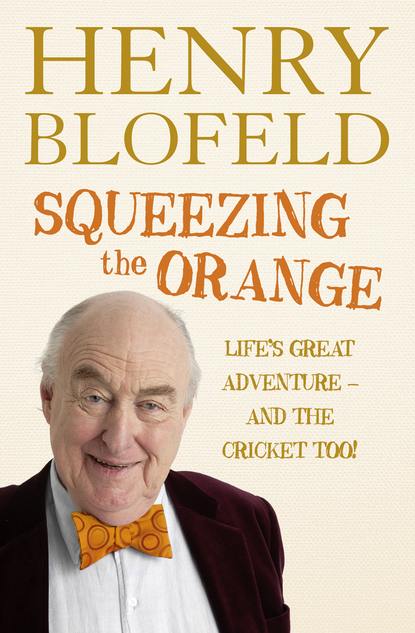

Squeezing the Orange

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The farm manager, the slightly austere, bespectacled and white-haired Mr Grainger, tootled about the place in his rather severe-looking car. I was extremely careful of him, for I knew that anything I got up to would go straight back to Tom. Mr Grainger had a small office in the Home Farm yard which I avoided like the plague. In fact I think it was a mutual avoidance. As far as I was concerned, Mr Grainger, who lived in a small house down the drive, was always hard work, and if he had a lighter side, I never found it. My father’s office was presided over by the ebullient, bouncing and eternally jolly, but not inconsiderable, figure of Miss Easter, a local lady from Salhouse who was a close ally of Nanny’s. I loved it when she paid us a visit in the nursery. ‘Miss Easter’ was a tongue-twister for the young, and she was known affectionately by all of us, including Grizel, as ‘Seasser’, although Tom never bent from ‘Miss Easter’. I suppose she must have had a Christian name, but I can’t remember it. Sadly for us, she left Hoveton when approaching middle age, and became Mrs Charles Blaxall. He was a yeoman farmer, and they lived somewhere between Hoveton and Yarmouth. I used to go with Nanny to visit her in her new role as a farmer’s wife. She remained the greatest fun, always provided goodies and was one of the real characters of my early life. I can hear her cheerful, echoing laughter even now.

Freddie Hunn, a small man with the friendliest of smiles, was in charge of the cattle feed, which was ground up and mixed in the barn across the yard from my father’s office. I loved to go and help Freddie. There was a huge mixer, which was almost the height of the building. All the ingredients were thrown in at the top, mixed, and then poured into sacks at the bottom. The barn had a delicious, musty smell. Freddie’s other role was to look after the cricket ground at the other end of the farmyard, through the big green gate and up the long grassy slope to Hill Piece. After his day in the barn had finished he would go up to the ground and get to work with the roller or mower or whatever else was needed. The day before a match between Hoveton and Wroxham and one of the neighbouring villages, out would come the whitener, and the creases would be marked. I found it all fascinating, and Nanny could hardly get me back to the house in time for a bath on Friday evenings.

Freddie was a great Surrey supporter, while I was passionate about Middlesex and Compton and Edrich. But Freddie always thought he had trumped my ace when he turned, as he inevitably did, to Jack Hobbs. Freddie’s wife, the large, smiling Hilda Hunn, supervised the delicious cricket teas, and sometimes allowed me a second small cake in an exciting, coloured paper cup.

One of my favourite farmworkers was Lennie Hubbard, whom we all, including my father, called by his Christian name. I never discovered why or how such distinctions were made: why most of the workers on the farm were known by their surnames, while Freddie, Lennie and one or two others went by their Christian names. Lennie was tall, and had been born in the Alms Houses in Lower Street, the rather upmarket name for the lane that ran past these cottages down to the marshes. Once, a great many years earlier, that lane had been part of the main road from Norwich to Yarmouth, which had originally gone past the front of Hoveton House. During the Second World War Lennie had been taken prisoner by the Germans, but had managed to escape – perhaps it was his gallantry that had caused his Christian name to be used. Tom always enjoyed talking to Lennie, and regarded him as one of his best and most faithful employees. There was an irony in that, as Lennie told me much later, long after Tom had died, he and one or two others, for all their outward godliness, had been diehard poachers. He told me, with a broad smile, of an occasion when one day my father had suddenly appeared around the corner of a hedge and spoken to him for ten minutes. Under his greatcoat Lennie was hiding his four-ten shotgun and a recently killed cock pheasant. I dare say he never came closer to losing both his job and his Christian-name status.

Shooting was another highlight of my early life. I fired my first shot when I was nine, missing a sitting rabbit by some distance. I am afraid I was the bloodthirstiest of small boys, and I have loved the excitement and drama of shooting for as long as I can remember.

Tom used to arrange six or seven days’ shooting a year with never more than seven guns. They would kill between one and two hundred pheasants and partridges in a day. As a small boy I found these days hugely exciting. Then there was the early-morning duck flighting on the Great Broad. This was always a terrific adventure, getting up in the dark and eating bread and honey and drinking Horlicks in the kitchen before setting off by car for the Great Broad boathouse soon after five o’clock in the morning. There was also the evening flighting on the marshes, when each of us stood in a small butt made of dried reeds. This was also thrilling, and of course by the time we got home night had set in.

Carter was the first gamekeeper I remember. He was a small, rather gnarled man with a lovely Norfolk voice. Apart from looking after the game and trying to keep the vermin in check, his other job each morning was to brush and press the clothes my father had worn the day before. He did this on a folding wooden table on the verandah by the back door. When he had done this, if I asked politely and he was in an obliging mood, he would come out to the croquet lawn and bowl at me for a few minutes. I had to tread carefully with Carter. I think he was the first person ever to bowl overarm to me with a proper cricket ball. Sometimes I hit him into the neighbouring stinging nettles, which ended play for the day, for his charity did not extend to doing the fielding off his own bowling. Carter was the village umpire during the summer. I’m not sure about his grasp of the laws of the game, but you didn’t question his decisions – you merely moaned about them afterwards. When Carter retired he was succeeded by Watker, a brilliant clay-pigeon shot and, to me, a Biggles-like figure; and then by Godfrey, the nicest of them all. I would spend a huge amount of time with the keepers during the holidays. Once or twice I looked after Godfrey’s vermin traps when he had his holiday. Sadly, neither Watker nor Godfrey had a clue how to bowl, but Nanny, who was up for most things, would bowl to me on the croquet lawn. Her underarm offerings often ended up in the nettles, and being the trouper she was, she would dive in after them, and usually got nastily stung.

It was a fantastic world in which to be brought up. Looking back on it, it was quite right that I should have been taught how to use it and respect it. I can almost feel myself forgiving Tom for those cherries. In a way it was sad when my full-time enjoyment of Hoveton came to an end. But when I was seven and a half I was sent away to boarding school at Sunningdale, almost 150 miles away, which may now seem almost like wanton cruelty, but was par for the course in those days. When I was young, all I wanted to do was to grow older, and going away to school seemed a satisfactory step in the right direction.

TWO (#ulink_3d8793ee-5e31-5732-a037-04071e80d6a2)

A Wodehousian Education (#ulink_3d8793ee-5e31-5732-a037-04071e80d6a2)

I was not unduly alarmed at the prospect of being sent away to school. John had been to Sunningdale, and had survived, although of course as he was seven years older than me, we were never at school together. Grizel had been calling me ‘Blofeld’ for some while before I went, for she wanted to make sure that I would be used to being called by my surname when I got to the school. For some reason I was not made to call Tom ‘sir’, which was how I would have to address the masters. Ordering the school uniform and all the other clothes I would need had gone on for weeks, and Nanny had sewn smart red name-tapes onto all the shirts, pants and stockings, revealing to anyone who chose to look – but principally, I suspect, the laundry – that they belonged to H.C. Blofeld. I won’t say I jumped happily into the back of my father’s dark-green Armstrong Siddeley in early May 1947, but I was nothing like as homesick as I was to become over the next couple of years when going back to school at the end of the holidays. I think Nanny was the person who minded it all the most, and she was probably the closest to tears amid the frantic waving as we tootled off.

The journey went on for nearly five hours before we turned left into the school drive, with rhododendrons on either side. We went up a short hill to what then appeared to me to be a huge gravelled area in front of the house, where half a dozen cars were parked. It all seemed uncomfortably large, and I think I began to quiver. I was greeted with formal handshakes by Mr and Mrs Fox, the headmaster and his wife. Mr Fox’s black hair gleamed with oil, which made him smell of mildly austere flowers. He was wearing a rather severe three-piece suit, with fiercely polished black shoes, and gave me an exceedingly creased half-smile. By now I was beginning to think I had been sold an ungovernably fast one by Tom and Grizel when they had told me what a smashing place Sunningdale would be.

Tom was being pleasantly avuncular in the background while Grizel, with considerable gusto, was shooing me around the Foxes’ drawing room to shake hands with everyone in sight. Having been through it all with John, she knew the leaders of the pack well enough, and briskly brushed aside an under-matron and a junior master. False bonhomie was very much the order of the day. I think we were all given a cup of tea and, who knows, a cucumber sandwich. Mrs Fox, wearing glasses and with a good deal of grey hair, did not exactly clutch me to her bosom. Her efforts to be kind did nothing to steady my nerves.

Most of the staff were present, including Matron, Miss Cryer, who had been at the school for many years and had once met Nanny when John was there. Nanny had generally given her the OK, and she made friendly noises at this somewhat stilted gathering as she bustled around with tea and whatever while Grizel told me to be careful not to spill crumbs on the carpet. Mr Burrows, Mr Fox’s second-in-command, was there, tall, stiffly formal, with a greyish moustache and a smile which resembled one of Carter’s gin traps in repose. We were eventually to become quite good friends, but I would never have guessed it at our first meeting. Mr Tupholme, ‘Tuppy’ to one and all, was grinning cheerfully away and doing his best to bring a touch of jollity to the proceedings. Tuppy was an all-round good egg. Mr Sheepshanks, quite a bit younger, was also cheerful in a black-moustached, ‘What-fun-it-will-all-be-oh-my-goodness-me’ sort of way, and Miss Paterson put in a tight-lipped appearance just to make sure things did not get too jolly. Conversation, if it can be called that, hardly flowed. There were two or three other new boys there with their parents. I have forgotten their names although I think one was Laycock, but I well remember being introduced to one by Mrs Fox, who said in a formal voice, ‘This is Blofeld.’ I was grateful for Grizel’s tuition.

Being the start of the summer term, there was not the influx of new boys that arrived in late September at the start of the school year. We were taken by Mrs Fox and Matron to see the lower dormitory. I was shown the bed in which I was going to sleep, and I think an under-matron may have flitted by. Grizel came with us, and kept telling me how much I would enjoy it once I got used to it. I wished I had shared her confidence. There must have been eight or ten beds, a wash stand and a bowl for each of us in a row at the foot of the beds, a po cupboard underneath, and a basket under the bed for the clothes I would take off before jumping into my pyjamas. The longer this introduction to my new quarters went on, the more I felt my enthusiasm draining. Then it was back along the passages, the walls of which were covered with school groups from prehistoric times. One new boy was shown a photograph and told, ‘There’s your father.’ I hope it gave them both encouragement. It was not long after that that Tom and Grizel decided the time had come for them to leave. Tom certainly never specialised in emotional farewells, and Grizel did her best, giving me the briefest of pecks on the cheek, although she will have been alarmed by the thought that I might burst into tears. Then I watched, helpless, as they strode across the gravel to the car, got in, started the engine and disappeared from view. I was well and truly on my own, and I didn’t like the look of it. I managed not to blub which would have been letting the side down.

I was the youngest boy in the school, and, funnily enough, found this to be a good deal more of a liability than I had expected. It seemed to bring in its wake a disdainful hostility rather than the sympathy I had hoped for. The lower dormitory passed off without too much worry, but I had problems a term or two later for as soon as I was promoted to the upper dormitory, I got on the wrong end of some nasty bullying. There was a monitor in each dormitory who slept in a bed by the door. He didn’t come up until about two hours after the rest of us, which left scope for bullying. Next door to him was a little horror who I don’t think I’ve seen since the day he left Sunningdale, although he probably went on to Eton – most of the boys did, but I don’t remember him there. He forced me to do a number of things which went severely against the grain.

The worst was when I was made to go to the stairwell with my tortoiseshell-backed hairbrush, which had a piece of sticking plaster on it proclaiming ‘Blofeld’ in bold ink. Then, as the girl who carried the cocoa and the cups to the library for the older boys before they went to bed walked underneath, I was instructed to drop the hairbrush so that it landed on the tray, or better still, hit her on the head. Mercifully, I didn’t get it right – if I had, it might have finished her off – and the brush fell with a sickening thud on the floor beside her. She was a good girl, because she didn’t drop the tray or swerve or even scream, but carried steadfastly on. However, retribution was swift. I was in appalling trouble, and came head-to-head for the first time with Mr Burrows, who lived in a part study, part bedroom and part torture chamber in which there was a visible array of canes sticking out of a tall basket which he was never reluctant to use. And when he did, he put a good deal more vim into it than Mr Fox. For some strange reason, Mr Burrows did not tell me to bend over on this occasion. I have no idea what I said to him about the incident, but I didn’t sneak, for that would have meant that my life in the upper dormitory and everywhere else would have been hell. Sneaking was the worst of crimes.

I am not sure why I got away with this early misdemeanour so lightly. It may have been that the powers-that-were had a fair idea of why the hairbrush incident had happened. Mr Burrows had an armour-plated exterior, but a streak of kindness underneath, even if, for the most part, he disguised it well. Anyway, if I was still able to recognise the chap who forced me to drop the hairbrush, I would even now be sorely tempted to step across the street and have a word with him. His name was Baring, and he was almost certainly one of the banking lot. I remember thinking all those years later what a splendid chap the wretched Nick Leeson must have been, and how miserably he was treated. He had no greater supporter than me. I mean, to be sent to a Singaporean gaol for performing such a notable public service …

I couldn’t have enjoyed Sunningdale too much at the start of my five years there, because I was terribly homesick, and at the end of the holidays I had to be hauled off back to school. I howled outrageously in the car most of the way. But not everything was bad. I dipped my toes into the waters of cricket for the first time in my first term, and fell for it just like that. There were other good things too. The sausages we had for breakfast once a week – Wednesdays I think – were delicious, although the daily dose of porridge which preceded them was more awful than anything I have ever eaten in my life. We were made to finish it, then or at lunch, and I have never eaten porridge since. Even the unspeakable mincemeat we were given for lunch on Fridays, which gloried in the splendid name of ‘Friday Muck’, was a couple of lengths better than the porridge and I have struck up a more meaningful relationship with the present-day equivalent of Friday Muck. The name was invented by my contemporary at the school Nicholas Howard-Stepney from the family which owned Horlicks. He was also responsible for Wednesday lunch’s ‘Pharaoh’s Bricks’, a cake pudding cut in Eastern European-like rectangular blocks with the merest soupçon of jam on the top, and ‘Thames Mud’, a terrifyingly solid chocolate blancmange which seemed both to wobble and frown at you. I suppose post-war food rationing hardly helped Mrs Fox when it came to creating the menu.

The cast at Sunningdale was nothing if not Wodehousian. Mr Fox, who went by the Christian names of George Dacre (PGW had a housemaster called Dacre in Tales of St Austin’s), had signed up in 1906. Maybe there was something of the Reverend Aubrey Upjohn (Bertie Wooster’s private-school headmaster) in Mr Fox, and I have no doubt that they would have hit it off like a couple of sailors on shore leave. By the time I met Mr Fox his face was inordinately lined, craggy and ancient, and would have made the Gutenberg Bible look to its laurels. To us, Mr Fox seemed older than God, and spoke in a slow, sepulchral tone that did nothing to make me think I was about to make a lifelong friend. He frightened me out of my socks, and beat me in the fourth-form classroom at the top of the stairs on the left whenever I kicked over the traces. A stern lecture would be followed by six relatively mild strokes, after which I would be told to leave. As many of the other boys as possible would have been standing outside the door to count the number of strokes. Six was the usual complement, but for something truly hideous, the count may have reached eight, making the recipient a sore-bottomed hero, but even to receive six did your street cred no harm. Mr Fox was known to us as ‘Foe’, and come to think of it, it was not a bad nickname, for I don’t think I ever felt entirely convinced that he was on my side. He was five foot seven or eight, and his strong head of black hair was combed back and much adorned with Mr Thomas’s finest unction. Mr Thomas was the school haircutter, and he came down from his HQ in Bury Street SW1 twice a term with two or three of his cohorts to cut our hair. Several masters had their hair cut too, including Foe, who was on Christian-name terms with the rotund, avuncular, noisy and highly genial Mr Thomas, who laughed a good deal as he snapped the scissors like the well-seasoned performer he was. I don’t know why, but it went slightly against the grain that Mr Fox was on first-name terms with his barber. When the two of them laughed there was always something slightly conspiratorial in the air, as if they were planning a visit to a particularly shady club.

Mr Fox took the fourth form, and never encouraged jocularity, although there were times when I am sure he felt he was being the star of the party. But he always made teaching seem a solemn business, and was seldom fun and never funny. He had written a well-known green-covered history date book, which was not so much compulsive as compelled reading. It was all there, from Hengist and Horsa and Ethelred the Unready to the present day. Mr Fox was as proud of his date book as if he had made up the dates himself and given the history of this country both order and meaning. He did have another side to him – to keep themselves sane, a good many schoolmasters must lead double lives. The day the term finished at Sunningdale, the sofa in the Foxes’ drawing room was pushed back, and out came the bridge tables, swiftly followed by the packs of cards and scoresheets, and then by those of his neighbours who participated. The stakes were said to be high; I imagine Foe was probably a gambler, but in a guarded rather than a reckless manner. I should think he was a pretty good player who seldom settled for three no trumps when a slam was in the air.

He was a great racing man too, and a number of important trainers sent their boys to Sunningdale. Cecil Boyd-Rochfort’s twin stepsons, David and Henry Cecil, were naughty and great fun. Of course Henry went on to become a remarkable trainer in his own right, picking up a knighthood and Frankel along the way before dying horribly of cancer. Peter Cazalet, the Queen Mother’s trainer, sent both his sons to Sunningdale. Edward, the elder, became a High Court judge, and as his mother, Leonora, had been PGW’s stepdaughter, controls all things Wodehouse today with charm, skill and high good humour. Noel Cannon’s son was also at the school. Royal Ascot week caused a good deal of activity on the private side, as Mr Fox’s quarters were known. Lots of chaps were seen wandering about the place in morning coats and silk toppers, and ladies in extravagant hats were plentiful. I don’t think a hat, however extravagant, would have made a significant difference to Mrs Fox, who may once have been a great beauty, but if she had been, by the time I met her she was playing from memory.

I don’t know if Foe’s gambling inclinations explored other avenues. I doubt that he was a casino man, unlike R.J.O. Meyer, the famous headmaster of Millfield, who when the day’s duties were over would drive all the way from Somerset to a gaming club in Mayfair with a goodly portion of that term’s school fees in his trouser pocket. Rumour has it that when he plonked it all on red, black almost invariably turned up. On the somewhat daunting return journey in the middle of the night I dare say he would have found it difficult to stick to the speed limit.

To us boys there was no visible lighter side to dear old Foe, who said grace before lunch with a basso profundo solemnity and sang in chapel in a toneless voice somewhere around the baritone mark. He never made much of the high notes. His sermons always seemed to contain some less than compelling strictures; Mr Burrows was not a giggle a minute in the pulpit either and he made it all too plain what the devil had in store for us if we didn’t look sharp. They both made you feel they were arm in arm with the wrath of God. Tuppy took the services in chapel, and wore a surplice as a jovial sort of holy disguise. Miss Paterson (‘Patey’), who sang with a rigorous and tuneless vigour, sat two rows behind the Foxes, who were immediately behind us new boys. Mr Ling, whom we have not yet come across, and who more closely resembled a Chinese god than any Chinese god I have ever seen, did his best in the row in between. The more jolly Mrs Ling clocked in only on Sundays. They sang dutifully, while Mr Sheepshanks, ‘Sheepy’ to us all, played the organ and sang enthusiastically at the same time. Psalms were always harder work than the hymns, and I was glad when we had got the Magnificat and the Te Deum out of the way as well.

Mrs Fox went by the name of Nancy, which didn’t really fit the bill – although Lucretia would have been a bit too severe. I can’t remember Mr Fox ever looking dreamily at her and murmuring, ‘Nancy.’ Maybe he only did this in extremis. Anyway, she remorselessly called him ‘Foxy’, and they begat two sons, both Sunningdalians. By the time I came across George Dacre and Nancy, I suspect they were well past moments of high passion, and neither of them appeared particularly flighty. Mrs Fox looked a little bit like my idea of B. Wooster’s Aunt Agatha, with more than a touch of Lady Constance Keeble, Lord Emsworth’s bloody-minded sister, thrown in. She gave out boiled sweets by the stairwell outside the dining room after lunch on Sundays, Tuesdays and Thursdays with gratuitous suspicion. Eight on Sundays, six on Thursdays, and a chocolate or Mars bar on Tuesdays. They were counted with great exactitude. If, on a recount, she discovered one sweet too many, it was a capital offence and you were lucky if she only took two away.

Mr Burrows was number two in the batting order after Mr Fox, and he didn’t come across well. To a small boy he was alarming, and anyone could be forgiven for thinking at first that he was an all-round shit. I don’t think he liked or felt comfortable with the smallest boys, and there was always a suspicion that he may have been a repressed homosexual. As far as Wodehouse was concerned, most of the time Burrows would have made Roderick Spode, alias Lord Sidcup, alias Oswald Mosley, seem a decent sort of cove. He was slim, reasonably tall and slightly bent. I think he probably had a sense of humour, but he was careful whom he showed it to. When I first came across him he was very much the Dickensian schoolmaster, but if, for whatever reason, you came into prolonged contact with him – as I did when I kept goal for the school and went on to become an unlikely captain of soccer – he was much easier. I then found a friendlier, more amenable side to him. Perhaps he was rather shy at heart, and it was only when he felt comfortable with certain boys that his outer shell fell away. I never knew what his football qualifications were, but obviously he knew a bit about the game. Whenever we played against other schools he would be mildly unforgiving at half time as we surrounded him in a group, each sucking a quarter of a raw lemon in the hope that it might turn us into Stanley Matthews. Burrows was a serious supporter of Newcastle United, and if you mentioned Jackie Milburn there was an outside chance that he might smile, and he would certainly look more favourably upon you. George Beaumont, a good friend of mine who was a member of the Allendale family, came from Northumberland, and was also passionate about Newcastle and Milburn, which meant that he and Mr Burrows became friends. He was a fine outside right, who ran fast and controlled the ball well. George was sadly killed in an aeroplane crash in New Zealand soon after leaving Eton.

Mr Burrows lived in a room, full of heavy dark-brown furniture, between the upper dormitory and the upper cubicles, from where he administered justice and discipline. He was a recognised and fully-paid-up beater, and a cane in his hands was much more a weapon of war than in Mr Fox’s. His initials were JB – for John Berry, perhaps – and his nickname was ‘Budgie’. I never remember any of his teaching colleagues slapping him on the back and calling him John, or Berry for that matter. When I joined the third form, over which he presided, I found him frighteningly unforgiving. If you were clever and were at the top of the form and gained his respect, he was a bit better. If it had not been for the soccer I would have got it in the neck.

I wonder if Mr Burrows was ever truly happy. But before we leave him, I should mention that when some of us had reached a certain age, he would allow us into his room by the upper dormitory at a quarter to seven in the evening to listen to Dick Barton, Special Agent. Agog, we followed the machinations of Barton, Snowy, Jock and the others as though our lives depended upon the breathtaking drama. Dick Barton was definitely not Mr Burrows’ cup of tea, and he never stayed to listen. Later in life I wondered if Mr Burrows ever found an obliging woman. I doubt it. But then, did he ever want one? I imagine every private school in those days had its Mr Burrows.

Miss Paterson, or Patey, who came onto the books in 1940, was not quite polished enough to have been a contender for the Lady Constance Keeble spot, but she, like Mrs Fox, would have been a definite runner for aunt-like status. I think she and Aunt Agatha would have got along pretty well, although she had about her more than a hint of Rosa Klebb, who made James Bond’s life pretty uncomfortable in From Russia, with Love. The debate about her Christian name continues. ‘Emmeline’ has its supporters, but ‘Eileen’ is probably just the favourite. They both fitted. She was spectacularly uncompromising, and did not tolerate nonsense in any way whatever. If she had a sense of humour, she wasn’t letting on. She had the unfortunate habit of shaping her ‘R’s with a loop, as they appear on Harrods vans. This particularly distressed Nicholas Howard-Stepney who spoke contemptuously of ‘Patey Rs’. Patey had a feminine enough shape, but with a keep-your-distance sort of face – and never to my knowledge did she have a single suitor. I think she would have discouraged passion in any form, and might not have been very good at it. She wore sensible shoes and even more sensible stockings, and spoke like a regimental sergeant-major. I can’t imagine her in a warm, let alone a passionate embrace, although people who give that impression can sometimes come up against the wind. Patey was also, rather surprisingly, my first cricketing mentor. She was in charge of the third-form game, and was forever marshalling the troops. The game was played on a small piece of roughish ground somewhere between the raspberry cages and the railway line, which may give it a romantic connotation it does not deserve.

Miss Paterson must have been in her upper thirties, and there was a fair amount of her. She wobbled a good deal, both fore and aft. She loved to take part in the cricket, or at any rate she felt it was her duty to do so. I don’t ever remember her batting, but she always opened the bowling. The pitch was only about fifteen yards long, if that, and while there were two sets of stumps, there were no bails. We had puny little bats, but there were no pads or gloves, and boxes were not even a gleam in anyone’s eye. Patey ran in off about five paces, and bowled underarm with a certain nippiness. If she hit you on the shin, it made you yelp a bit, and she would launch herself into an extravagant, almost Shane Warne-like appeal. This was a little strange, because there was no umpire. That didn’t worry her in the least, because she immediately metamorphosed herself into the umpire and gave you out. You certainly did not question her decision. She wasn’t the worst bowler, and I can tell you that her swingers went both ways all right.

They were the first swingers I ever took a serious interest in. She had another interesting physical attribute: her front teeth were unstoppable. If you ran round a corner in a passage in the school and she was there, you would put your hands up in front of your face to protect yourself from the upper lot. I remember thinking some years later that if there was such an event at the Olympic Games as eating corn on the cob through a Venetian blind, Miss Paterson would have been on top of the rostrum accepting the gold medal and shaking up the champagne with the best of them.

As far as the runners and riders were concerned at Sunningdale, those were most of the bookies’ favourites. But there was also a pretty good list just behind the leaders. Charlie Sheepshanks, ‘Sheepy’, who had clocked in from the Brigade of Guards soon after hostilities had been concluded in 1945 with a scar on his face which was evidence of close contact with the enemy, was a congenial, Bertie Wooster-like figure. His brother had been killed in the Spanish Civil War, and at Sunningdale Sheepy lived with his mother in a house in the grounds. He played the organ in chapel, or the tin tabernacle, as we knew it, and did so with a certain brio. Good-looking, black-moustached with a ready smile, a bit of a leg-spinner and greatly liked by us all, he shared Mr Fox’s schoolroom where he presided over maths, genially, unpretentiously, amusingly and with indefatigable cheerfulness. He was the dearest of men, and went on to marry Mary Nickson, who was the daughter of my first housemaster at Eton. He also ran the cricket at Sunningdale, taking over from a Mr Kemp, who left soon after I arrived.

After Sheepy retired from educational activities, he and Mary moved to his family home in the village of Arthington in Wharfedale, where they would entertain the Test Match Special team to dinner in splendid style during the Headingley Test match. The banter between the Bishop of Ripon and Jim Swanton will not easily be forgotten. Jim regarded the bishop as an extremely close cohort of the Almighty, and tried to speak to him with a humble sanctity, while the bishop, who was only a suffragan, would leave religion at home for the evening. Sheepy was a passionate gardener and fisherman, and a great friend of Brian Johnston – they were both infectious laughers – with whom he fought innumerable battles on the tennis court. He was also a wizard on the Eton fives court. While at Sunningdale – of which he became headmaster for a time after Fox had retired – he joined forces with J.M. Peterson, an Eton housemaster whose sons were at Sunningdale, and together they won the old boys’ Eton fives competition, the Kinnaird Cup, for year after year. For me, Charlie Sheepshanks was a real-life mixture of Biggles, Bulldog Drummond and Bertie Wooster.

Then there was Mr Tupholme, who came from Bournemouth or thereabouts, and was a long-standing taker of the fifth form. He was an excellent schoolmaster who made everything fun for the boys, while the more solemn members of the staff across the landing would have made the prophet Job seem a bit of a laugh. We listened to Tuppy because he had the knack of making everything fun, but interesting and important at the same time. He was in charge of rugger in the Lent term, bowled a bit in the nets during the summer, and presided genially over the swimming pool. Everyone loved him. Medium-height, plump, eternally cheerful, eyebrows that curled like Denis Healey’s, he was never fierce, never shouted, and bought us Dinky Toys to order on his frequent visits to Windsor. As a boy, one always felt that Tuppy was up for anything, and we loved him. PGW would have turned him into Lord Ickenham. Another of Tuppy’s sidelines was the model railway, which he organised in the Army Hut, a rather Spartan, military-looking building at the far end of the school where the school concert was held. In my first concert, which Tom and Grizel dutifully, and I suspect reluctantly, attended, I had to sing one verse of ‘Cock Robin’. I doubt there has ever been a more tuneless rendering of any song since mankind first put its larynx on the stage.

I have briefly mentioned Mr Ling, who was the Venerable Bede of Sunningdale, and an awesome figure. Like Mr Fox and Mr Burrows, he had joined up with the school before the First War. He was a classical scholar, and was the principal reason why Sunningdale won so many scholarships, mainly for Eton, where most of its pupils ended up. Mr Ling was a genius as a schoolmaster. He took the sixth-form classics, and taught Greek and Latin with astonishing skill and amazing results. His most famous top scholar was Quintin Hogg, who went on to become Lord Hailsham and the Lord Chancellor, and who paid Mr Ling a most generous tribute in his autobiography, The Door Wherein I Went. When I first came across Mr Ling I thought he was even older than Methuselah. He was gruff, quietly and classically humorous, and his gleaming and absolute baldness positively oozed Greek and Latin verse and always looked as if he was made of jade. He was wisdom personified, and wore his rimless glasses in a way that suggested they were an essential adjunct to classical scholarship. He was also a passionate man of Suffolk. This gave us both a certain East Anglian affinity – I did not have the smallest affinity with the classics – even if he regarded Norfolk as the lesser of two equals. Lord Emsworth might have had dinner with him by mistake at the Senior Conservative Club in St James’s.

Mr Ling always came hurriedly into the classroom as if he had just bumped into Socrates on the stairs and, with time running short, had had quickly to put him right about a couple of things. Having virtually lost the use of his right hand by kind permission of the Kaiser in the First War, he wrote on the blackboard and elsewhere with his left hand, and in doing so was magnificently illegible. You needed to have been on the payroll at Bletchley Park to have had the slightest chance of interpreting his offerings. He did not suffer fools gladly, and as I remember he found it jolly nearly incomprehensible that anyone could be as stupid and as unreceptive to the classics as I was. He had a good sense of humour, a pleasant chuckle, and bowled gentle slow left-arm in the nets when it came to the summer term. I don’t think he ever looked much like getting anyone out, but that did not prevent him from having firm views on the forward defensive stroke.

Just occasionally I was asked to tea with Mr and Mrs Ling at their house in nearby Charters Road. Mrs Ling, who was kind in a charming, elderly way, provided more than acceptable strawberry jam and a tolerable scone or two and always loved to pull her husband’s leg. Mr Ling, because of his injured hand, was not as accurate with the teapot as he had been in his heyday, and Mrs Ling was more than prepared to give him a bit of stick for this. He would laugh at his failing, and was always more fun outside the classroom than in it. He was a remarkable man, a brilliant teacher and a friend in a slightly distant, but loyal way, even if academically you were batting well down the order.

Bob (R.G.T.) Spear was young, tall and fair-haired, and taught goodness knows what for a time. He had an electrifying affair with the under-matron, Kitty Dean, whom he married. I once caught her sitting on his knee in the tiny masters’ room between Mr Fox’s and Mr Ling’s schoolrooms, which was as near as one came in those days to hard porn. The marriage did not last, and he eked out his days as a rather penniless handicapper at Newmarket, where he died. I once or twice came across him in the Tavern at Lord’s during a Test match. A long time before, he had bowled fast for Eton: Bingo Little, perhaps, although he never met his Rosie M. Banks.

There was the altogether more garrulous and clubbable Eustace Crawley, son of the immortal golfing correspondent Leonard Crawley, who wrote for the Daily Telegraph for many years. Leonard had also been a master at Sunningdale in the twenties, and in 1925 he was picked to tour the West Indies with the MCC. He was always greatly encouraged with his golf by Mr Fox, who was captain of Sunningdale Golf Club in 1940. This was the reason why in the winter whenever it was shut we were allowed to play French and English on the course.

Eustace must have taught something, but in those days he seemed to be Gussie Fink-Nottle to his eyebrows, and was immense fun without appearing to be devastatingly effective. This was a completely false impression, for he not only won a golf Blue at Cambridge for three years, but ended up as managing director of Jacksons of Piccadilly – Gussie F would have had no answer to that. I remember lots of floppy dark hair and a most engaging chuckle.

There was also the ever genial, tall and robust Mr Squarey, who was poached from neighbouring Lambrook. He was fun, with grey hair and glasses, and was up for everything when it came to games. He also bowled a bit in the nets, without devastating effect, but he was full of good honest cricketing theory, and always gave terrific encouragement. He was a friend.

Finally there was Matron Cryer, a veritable, and adorable, Florence Nightingale who never failed to make you feel better, and could even persuade you that the weekly dose of cod-liver oil tasted pretty good. I personally went for syrup of figs, which was a legitimate alternative and tasted much nicer. Her deputy, who later reigned for years as her successor as matron, was the indomitable Pauline, who was to become every bit as much an intrinsic part of Sunningdale as Mr Fox or any of the others. I suspect she enjoyed a bit of mischief too, and she and Roberta Wickham would have hit it off. Pauline was a great character, and before I left Sunningdale she gave me a photograph of the England side to tour Australia in 1928–29.

I may have missed one or two, but what fun it was. I lived in this milieu for five years, climbing my way up the pole under the auspices of the above-mentioned dramatis personae. I played in the cricket first eleven for four years – having moved fairly rapidly from being a leg-spinner to a wicketkeeper, and I think I could always bat a bit – and in the soccer team for two. I also played fives for the school, against Ludgrove, and we invariably lost. The only real blot was my consistent slacking on the academic side of things.

My years in the Sunningdale first eleven were fantastic fun. The star of the side was Edward Lane Fox and we not only played together in the first eleven for four years at Sunningdale, we also both played for Eton for three years. He was a wonderful all-round cricketer with the discipline I always lacked. Edward also won his colours at soccer and rugger, an impressive triple Blue. He was a remarkable games player, a cricketer who went on to play for Oxfordshire and for the Minor Counties against at least two touring sides and then became an estate agent, running his own eponymous firm with a brilliance few could have matched. He also hits a pretty mean golf ball. It would be hard to imagine a kinder, more charming and less pretentious man. He has never changed in character or in looks, and well into his seventies he is still easily identifiable as the chap sitting in the captain’s seat in the 1952 Sunningdale cricket eleven photograph. Edward was a wonderful orthodox left-arm spinner who bowled with great accuracy and turned the ball sharply away from the right-hander. The representatives of Earlywood, Scaitcliffe, St George’s, Lambrook, Heatherdown and a few other schools could make little of it. As a result, stumped Blofeld bowled Lane Fox was an oft-repeated dismissal.

Edward was also an excellent and solid left-hand batsman. The one school we had difficulty with was Ludgrove, who collectively played left-arm spin more than adequately. I think I am right in saying that the last time Sunningdale beat Ludgrove home and away in the same season was in 1952, which was Edward’s and my last year. Sunningdale may have started a trifle gloomily for me, but success on the playing fields turned it into huge fun, and rapidly put an end to all that silly homesickness.

I was given my first-eleven colours for cricket when the team photograph was about to be taken at the end of the 1950 summer term, my second year in the side. Later that afternoon I was ferried off by Mrs Fox to St George’s hospital in Windsor to have my tonsils removed. I remember Matron packing my new dark-blue cap, and when Mrs Fox unpacked my case at the hospital she thrust this cap under my pillow. When you got your colours this was the accepted modus operandi. The nursing sister was more than mildly surprised, but Mrs Fox pretty well told her to mind her own business. I never felt closer to her than I did at that moment, and I was able, with considerable pleasure, to try on the cap during the night. I had to wait until the chap with whom I shared a room, who probably wouldn’t have understood, was asleep.

What an adventure Sunningdale was and a splendid way to start learning about the highs and lows of life. In the schoolroom I was never remotely a candidate for a scholarship to anywhere except Borstal, but I suppose I did just about enough work to get by, and when I came to take Common Entrance to Eton, I achieved a humble middle fourth, which was lower than was hoped, but probably higher than was feared. I was never any good at exams. That rather apprehensive five-hour journey in my father’s old green Armstrong Siddeley at the start of May five years before had been well worth it. In the end Grizel had got it right, as she usually did.

THREE (#ulink_7e07a20e-f9cc-5676-9e31-61f1781e2870)

The French Women’s Institute (#ulink_7e07a20e-f9cc-5676-9e31-61f1781e2870)

Cricket had me in its grip before I had been at Sunningdale for a year. The following June, in 1948, I found myself at Lord’s with Tom and Grizel sitting on the grass in front of Q Stand eating strawberries they had brought up from Hoveton and watching the third day of the second Test against Australia. I became one of what is now a sadly diminishing band of people to have seen the great Don Bradman bat. He made 89 in Australia’s second innings before being caught at shoulder-height by Bill Edrich at first slip off Alec Bedser. I can still see the catch in my mind’s eye. As he departed, dwarfed by that wonderful and irresistible baggy green Australian cap, I was sad that he hadn’t got a hundred, but everyone else seemed rather pleased. I distinctly remember him facing Yorkshire’s Alec Coxon, a fast bowler playing in his only Test match. A number of times Coxon pitched the ball a little short, and Bradman would swivel and pull him to the straightish midwicket boundary, where we were sitting on the grass. Once I was able to touch the ball – what a moment that was.