По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

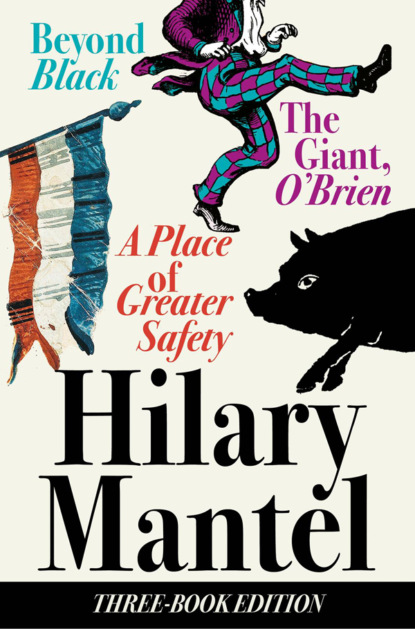

Three-Book Edition: A Place of Greater Safety; Beyond Black; The Giant O’Brien

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Well…’ Maître Desmoulins considered this large question. ‘People like me, men of the professional classes, we would like a little more say, I suppose – or let me put it this way, we would welcome the opportunity to serve.’ It is a fair point, he thinks; under the old King, noblemen were never ministers, but, increasingly, all the ministers are noblemen. ‘Civil equality,’ he said. ‘Fiscal equality.’

Condé raised his eyebrows. ‘You want the nobility to pay your taxes for you?’

‘No, Monseigneur, we want you to pay your own.’

‘I do pay tax,’ Condé said. ‘I pay my poll tax, don’t I? All this property-tax business is nonsense. And so, what else?’

Desmoulins made a gesture, which he hoped was eloquent. ‘An equal chance. That’s all. An equal chance at promotion in the army or the church…’ I’m explaining it as simply as I can, he thought: an ABC of aspiration.

‘An equal chance? It seems against nature.’

‘Other nations conduct themselves differently. Look at England. You can’t say it’s a human trait, to be oppressed.’

‘Oppressed? Is that what you think you are?’

‘I feel it; and if I feel it, how much more do the poor feel it?’

‘The poor feel nothing,’ the Prince said. ‘Do not be sentimental. They are not interested in the art of government. They only regard their stomachs.’

‘Even regarding just their stomachs – ’

‘And you,’ Condé said, ‘are not interested in the poor – oh, except as they furnish you with arguments. You lawyers only want concessions for yourselves.’

‘It isn’t a question of concessions. It’s a question of human beings’ natural rights.’

‘Fine phrases. You use them very freely to me.’

‘Free thought, free speech – is that too much to ask?’

‘It’s a bloody great deal to ask, and you know it,’ Condé said glumly. ‘The pity of it is, I hear such stuff from my peers. Elegant ideas for a social re-ordering. Pleasing plans for a “community of reason”. And Louis is weak. Let him give an inch, and some Cromwell will appear. It’ll end in revolution. And that’ll be no tea-party.’

‘But surely not?’ Jean-Nicolas said. A slight movement from the shadows caught his attention. ‘Good heavens,’ he said, ‘what are you doing there?’

‘Eavesdropping,’ Camille said. ‘Well, you could have looked and seen that I was here.’

Maître Desmoulins turned red. ‘My son,’ he said. The Prince nodded. Camille edged into the candlelight. ‘Well,’ said the Prince, ‘have you learned something?’ It was clear from his tone that he took Camille for younger than he was. ‘How did you manage to keep still for so long?’

‘Perhaps you froze my blood,’ Camille said. He looked the Prince up and down, like a hangman taking his measurements. ‘Of course there will be a revolution,’ he said. ‘You are making a nation of Cromwells. But we can go beyond Cromwell, I hope. In fifteen years you tyrants and parasites will be gone. We shall have set up a republic, on the purest Roman model.’

‘He goes to school in Paris,’ Jean-Nicolas said wretchedly. ‘He has these ideas.’

‘And I suppose he thinks he is too young to be made to regret them,’ Condé said. He turned on the child. ‘Whatever is this?’

‘The climax of your visit, Monseigneur. You want to take a trip to see how your educated serfs live, and amuse yourself by trading platitudes with them.’ He began to shake – visibly, distressingly. ‘I detest you,’ he said.

‘I cannot stay to be abused,’ Condé muttered. ‘Desmoulins, keep this son of yours out of my way.’ He looked for somewhere to put his glass, and ended by thrusting it into his host’s hand. Maître Desmoulins followed him on to the stairs.

‘Monseigneur – ’

‘I was wrong to condescend. I should have sent my agent.’

‘I am so sorry.’

‘No need to speak of it. I could not possibly be offended. It is not in me.’

‘May I continue your work?’

‘You may continue my work.’

‘You are really not offended?’

‘It would be ungracious of me to be offended at what cannot possibly be of any account.’

By the front door, his small entourage had quickly assembled. He looked back at Jean-Nicolas. ‘I say out of my way and I mean well out of my way.’

When the Prince had driven away, Jean-Nicolas mounted the stairs and re-entered his office. ‘Well, Camille?’ he said. A perverse calm had entered his voice, and he breathed deeply. The silence prolonged itself. The last of the light had faded now; a crescent moon hung in pale inquiry over the square. Camille had retired into the shadows again, as if he felt safer there.

‘That was a very stupid, fatuous conversation you were having,’ he said in the end. ‘Everybody knows those things. He isn’t mentally defective. They’re not: not all of them.’

‘Do you tell me? I live so out of society.’

‘I liked his phrase, “this son of yours”. As if it were eccentric of you, to have me.’

‘Perhaps it is,’ Jean-Nicolas said. ‘Were I a citizen of the ancient world, I should have taken one look at you and popped you out on some hillside, to prosper as best you might.’

‘Perhaps some passing she-wolf might have liked me,’ Camille said.

‘Camille – when you were talking to the Prince, you somehow lost your stutter.’

‘Mm. Don’t worry. It’s back.’

‘I thought he was going to hit you.’

‘Yes, so did I.’

‘I wish he had. If you go on like this,’ said Jean-Nicolas, ‘my heart will stop,’ he snapped his fingers, ‘like that.’

‘Oh, no,’ Camille smiled. ‘You’re quite strong really. Your only affliction is kidney-stones, the doctor said so.’

Jean-Nicolas had an urge to throw his arms around his child. It was an unreasonable impulse, quickly stifled.

‘You have caused offence,’ he said. ‘You have prejudiced our future. The worst thing about it was how you looked him up and down. The way you didn’t speak.’

‘Yes,’ Camille said remotely. ‘I’m good at dumb insolence. I practise: for obvious reasons.’ He sat down now in his father’s chair, composing himself for further dialogue, slowly pushing his hair out of his eyes.

Jean-Nicolas is conscious of himself as a man of icy dignity, an almost unapproachable stiffness and rectitude. He would like to scream and smash the windows: to jump out of them and die quickly in the street.

THE PRINCE WILL SOON forget all this in his hurry to get back to Versailles.