По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

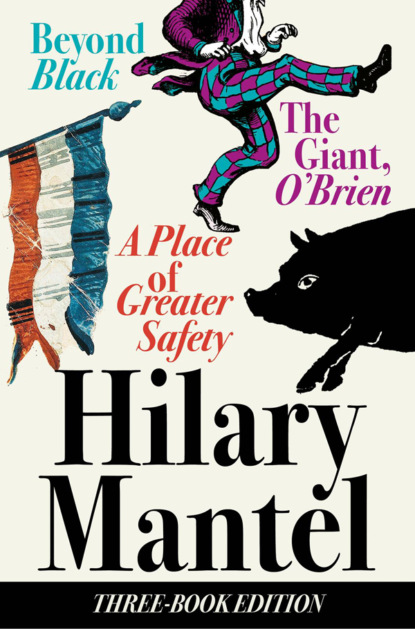

Three-Book Edition: A Place of Greater Safety; Beyond Black; The Giant O’Brien

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

I DON’T CARE what the Estates-General do,’ said Philippe d’Orléans, ‘as long as I am there when they deal with the liberty of the individual, so that I can use my voice and vote for a law after which I can be sure that, on a day when I have a fancy to sleep at Raincy, no one can send me against my will to Villers-Cotterêts.’

Towards the end of 1788 the Duke appointed a new private secretary. He liked to embarrass people, and this may have been a major reason for his choice. The addition to his entourage was an army officer named Laclos. He was in his late forties, a tall, angular man with fine features and cold blue eyes. He had joined the army at the age of eighteen, but had never seen active service. Once this had grieved him, but twenty years spent in provincial garrison towns had endowed him with an air of profound and philosophic indifference. To amuse himself, he had written some light verse, and the libretto of an opera that came off after one night. And he had watched people, recorded the details of their manoeuvres, their power-play. For twenty years there had been nothing else to do. He became familiar with that habit of mind which dispraises what it most envies and admires: with that habit of mind which desires only what it cannot have.

His first novel, Les Liaisons Dangereuses was published in Paris in 1782. The first edition sold out within days. The publishers rubbed their hands and remarked that if this shocking and cynical book was what the public wanted, who were they to act as censors? The second edition was sold out. Matrons and bishops expressed outrage. A copy with a blank binding was ordered for the Queen’s private library. Doors were slammed in the author’s face. He had arrived.

It seemed his military career was over. In any case, his criticism of army traditions had made his position untenable. ‘It seems to me I could do with such a man,’ the Duke said. ‘Your every affectation is an open book to him.’ When Félicité de Genlis heard of the appointment, she threatened to resign her post as Governor of the Duke’s children. Laclos could think of bigger disasters.

It was a crucial time in the Duke’s affairs. If he was to take advantage of the unsettled times, he must have an organization, a power base. His easy popularity in Paris must be put to good use. Men must be secured to his service, their past lives probed and their futures planned for them. Loyalties must be explored. Money must change hands.

Laclos surveyed this situation, brought his cold intelligence to bear. He began to know writers who were known to the police. He made discreet inquiries among Frenchmen living abroad as to the reasons for their exile. He got himself a big map of Paris and marked with blue circles points that could be fortified. He sat up by lamplight combing through the pages of the pamphlets that had come that day from the Paris presses; the censorship had broken down. He was looking for writers who were bolder and more outspoken than the rest; then he would make overtures. Few of these fellows had ever had a bestseller.

Laclos was the Duke’s man now. Laconic in his statements, his air discouraging intimacy, he was the kind of man whose first name nobody ever knows. But still he watched men and women with a furtive professional interest, and scribbled down thoughts that came to him, on chance scraps of paper.

In December 1788, the Duke sold the contents of his magnificent Palais-Royal art gallery, and devoted the money to poor relief. It was announced in the press that he would distribute daily a thousand pounds of bread; that he would defray the lying-in expenses of indigent women (even, the wits said, those he had not impregnated); that he would forgo the tithes levied on grain on his estates, and repeal the game laws on all his lands.

This was Félicité’s programme. It was for the country’s good. It did Philippe a bit of good, too.

RUE CONDÉ. ‘Although the censorship has broken down,’ Lucile says, ‘there are still criminal sanctions.’

‘Fortunately,’ her father says.

Camille’s first pamphlet lies on the table, neat inside its paper cover. His second, in manuscript, lies beside it. The printers won’t touch it, not yet; we will have to wait until the situation takes a turn for the worse.

Lucile’s fingers caress it, paper, ink, tape:

IT WAS RESERVED for our days to behold the return of liberty among the French…for forty years, philosophy has been undermining the foundations of despotism, and as Rome before Caesar was already enslaved by her vices, so France before Necker was already enfranchised by her intelligence…Patriotism spreads day by day, with the devouring rapidity of a great conflagration. The young take fire; old men cease, for the first time, to regret the past. Now they blush for it.

VI. Last Days of Titonville (1789)

A DEPOSITION to the Estates-General:

The community of Chaillevois is composed of about two hundred persons. The most part of the inhabitants have no property at all, those who have any possess so little that it is not worth talking about. The ordinary food is bread steeped in salt water. As for meat, it is never tasted, except on Easter Sunday, Shrove Tuesday and the feast of the patron saint…A man may sometimes eat haricots, if the master does not forbid them to be grown among the vines…That is how the common people live under the best of Kings.

Honoré-Gabriel Riquetti, Comte de Mirabeau:

My motto shall be this: get into the Estates at all costs.

NEW YEAR. You go out in the streets and you think it’s here: the crash at last, the collapse, the end of the world. It is colder now than any living person can remember. The river is a solid sheet of ice. The first morning, it was a novelty. Children ran and shouted, and dragged their complaining mothers out to see it. ‘One could skate,’ people said. After a week, they began to turn their heads from the sight, keep their children indoors. Under the bridges, by dim and precarious fires, the destitute wait for death. A loaf of bread is fourteen sous, for the New Year.

These people have left their insufficient shelters, their shacks, their caves, abandoned the rock-hard, snow-glazed fields where they cannot believe anything will ever grow again. Tying up in a square of sacking a few pieces of bread, perhaps chestnuts: cording a small bundle of firewood: saying no goodbyes, taking to the road. They move in droves for safety, sometimes men alone, sometimes families, always keeping with the people from their own district, whose language they speak. At first they sing and tell stories. After two days or so, they walk in silence. The procession that marched now straggles. With luck, one may find a shed or byre for the night. Old women are wakened with difficulty in the morning and are found to have lost their wits. Small children are abandoned in village doorways. Some die; some are found by the charitable, and grow up under other names.

Those who reach Paris with their strength intact begin to look for work. Men are being laid off, they’re told, our own people; there’s nothing doing for outsiders. Because the river is frozen up, goods do not come into the city: no cloth to be dyed, no skins to be tanned, no corn. Ships are impaled on the ice, with grain rotting in their holds.

The vagrants congregate in sheltered spots, not discussing the situation because there is nothing to discuss. At first they hang around the markets in the late afternoons, because at the close of the day’s trading any bread that remains is sold off cheaply or given away; the rough, fierce Paris wives get there first. Later, there is no bread after midday. They are told that the good Duke of Orléans gives away a thousand loaves of bread to people who are penniless, like them. But the Paris beggars leave them standing again, sharp-elbowed and callous, willing to give them malicious information and to walk on people who are knocked to the ground. They gather in back courts, in church porches, anywhere that is out of the knife of the wind. The very young and the very old are taken in by the hospitals. Harassed monks and nuns try to bespeak extra linen and a supply of fresh bread, only to find that they must make do with soiled linen and bread that is days old. They say that the Lord’s designs are wonderful, because if the weather warmed up there would be an epidemic. Women weep with dread when they give birth.

Even the rich experience a sense of dislocation. Alms-giving seems not enough; there are frozen corpses on fashionable streets. When people step down from their carriages, they pull their cloaks about their faces, to keep the stinging cold from their cheeks and the miserable sights from their eyes.

‘YOU’RE GOING HOME for the elections?’ Fabre said. ‘Camille, how can you leave me like this? With our great novel only half finished?’

‘Don’t fuss,’ Camille said. ‘It’s possible that when I get back we won’t have to resort to pornography to make a living. We might have other sources of income.’

Fabre grinned. ‘Camille thinks elections are as good as finding a gold-mine. I like you these days, you’re so frail and fierce, you talk like somebody in a book. Do you have a consumption by any chance? An incipient fever?’ He put his hand against Camille’s forehead. ‘Think you’ll last out till May?’

When Camille woke up, these mornings, he wanted to pull the sheets back over his head. He had a headache all the time, and did not seem to comprehend what people were saying.

Two things – the revolution and Lucile – seemed more distant than ever. He knew that one must draw on the other. He had not seen her for a week, and then only briefly, and she had seemed cool. She had said, ‘I don’t mean to seem cool, but I – ’ she had smiled painfully – ‘I daren’t let the painful emotion show through.’

In his calmer moments he talked to everyone about peaceful reform, professed republicanism but said that he had nothing against Louis, that he believed him to be a good man. He talked the same way as everybody else. But d’Anton said, ‘I know you, you want violence, you’ve got the taste for it.’

He went to see Claude Duplessis and told him that his fortune was made. Even if Picardy did not send him as a deputy to the Estates (he pretended to think it likely) it would certainly send his father. Claude said, ‘I do not know what sort of man your father is, but if he is wise he will disassociate himself from you while he is in Versailles, to avoid being exposed to embarrassment.’ His gaze, fixed at a high point on the wall, descended to Camille’s face; he seemed to feel that it was a descent. ‘A hack writer, now,’ he said. ‘My daughter is a fanciful girl, idealistic, quite innocent. She doesn’t know the meaning of hardship or worry. She may think she knows what she wants, but she doesn’t, I know what she wants.’

He left Claude. They were not to meet again for some months. He stood in the rue Condé looking up at the first-floor windows, hoping that he might see Annette. But he saw no one. He went once more on a round of the publishers of whom he had hopes, as if – since last week – they might have become devil-may-care. The presses are busy day and night, and their owners are balancing the risk; inflammatory literature is in request, but no one can afford to see his presses impounded and his workmen marched off. ‘It’s quite simple – I publish this, I go to gaol,’ the printer Momoro said. ‘Can’t you tone it down?’

‘No,’ Camille said. No, I can’t compromise: just like Billaud-Varennes used to say. He shook his head. He had let his hair grow, so when he shook his head with any force its dark waves bounced around somewhat theatrically. He liked this effect. No wonder he had a headache.

The printer said, ‘How is the salacious novel with M. Fabre? Your heart not in it?’

‘When he’s gone,’ Fabre said gleefully to d’Anton, ‘I can revise the manuscript and make our heroine look just like Lucile Duplessis.’

If the Assembly of the Estates-General takes place, according to the promise of the King…there is little doubt but some revolution in the government will be effected. A constitution, probably somewhat similar to that of England, will be adopted, and limitations affixed to the power of the Crown.

J. C. Villiers, MP for Old Sarum

GABRIEL RIQUETTI, Comte de Mirabeau, forty years old today: happy birthday. In duty to the anniversary, he scrutinized himself in a long mirror. The scale and vivacity of the image seemed to ridicule the filigree frame.

Family story: on the day of his birth the accoucheur approached his father, the baby wrapped in a cloth. ‘Don’t be alarmed…’ he began.

He’s no beauty, now. He might be forty, but he looks fifty. One line for his undischarged bankruptcy: just the one, he’s never worried about money. One line for every agonizing month in the state prison at Vincennes. One line per bastard fathered. You’ve lived, he told himself; do you expect life not to leave a mark?

Forty’s a turning point, he told himself. Don’t look back. The early domestic hell: the screaming bloody quarrels, the days of tight-lipped, murderous silence. There was a day when he had stepped between his mother and his father; his mother had fired a pistol at his head. Only fourteen years old, and what did his father say of him? I have seen the nature of the beast. Then the army, a few routine duels, fits of lechery and blind, obstinate rage. Life on the run. Prison. Brother Boniface, getting roaring drunk every day of his life, his body blowing out to the proportions of a freak at a fair. Don’t look back. And almost incidentally, almost unnoticed, a bankruptcy and a marriage: tiny Émilie, the heiress, the little bundle of poison to whom he’d sworn to be true. Where, he wondered, is Émilie today?

Happy birthday, Mirabeau. Appraise the assets. He drew himself up. He was a tall man, powerful, deep-chested: capacious lungs. The face was a shocker: badly pock-marked, not that it seemed to put women off. He turned his head slightly so that he could study the aquiline curve of his nose. His mouth was thin, intimidating; it could be called a cruel mouth, he supposed. Take it all in all – it was a man’s face, full of vigour and high breeding. By a few embellishments to the truth he had made his family into one of the oldest and noblest in France. Who cared about the embellishments? Only pedants, genealogists. People take you at your own valuation, he said to himself.

But now the nobility, the second Estate of the Realm, had disowned him. He would have no seat. He would have no voice. Or so they thought.

It was all complicated by the fact that last summer there had appeared a scandalous book called A Secret History of the Court at Berlin. It dealt in some detail with the seamier side of the Prussian set-up and the sexual predilections of its prominent members. However strenuously he denied authorship, it was plain to everyone that the book was based on his observations during his time as a diplomat. (Diplomat, him? What a joke.) Strictly, he was not at fault: had he not given the manuscript to his secretary, with orders not to part with it to anyone, especially not to himself? How could he know that his current mistress, a publisher’s wife, was in the habit of picking locks and rifling his secretary’s desk? But that was not quite the sort of excuse that would satisfy the government. And besides, in August he had been very, very short of money.

The government should have been more understanding. If they had given him a job last year, instead of ignoring him – something worthy of his talents, say the Constantinople embassy, or Petersburg – then he would have burned A Secret History, or thrown it in a pond. If they had listened to his advice, he wouldn’t be getting ready, now, to teach them the hard way.

So the Nobility rejected him. Very well. Three days ago he had entered Aix-en-Provence as a candidate for the Commons, the Third Estate. What resulted? Scenes of wild enthusiasm. ‘Father of his Country’, they had called him; he was popular, locally. When he got to Paris those bells of Aix would still be ringing jubilee, the night sky of the south would still be criss-crossed by the golden scorch-trails of fireworks. Living fire. He would go to Marseille (taking no chances) and get a reception in no way less noisy and splendid. Just to ensure it, he would publish in the city an anonymous pamphlet in praise of his own character and attributes.

So what’s to be done with these worms at Versailles? Conciliate? Calumniate? Would they arrest you in the middle of a General Election?

A PAMPHLET by the Abbé Sieyès, 1789:

What is the Third Estate?

Everything.