По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

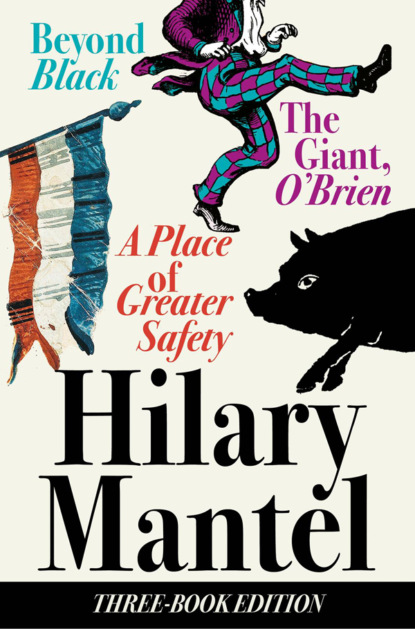

Three-Book Edition: A Place of Greater Safety; Beyond Black; The Giant O’Brien

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘He has no weaknesses, as far as I can see. And he certainly has no vices.’

Laclos was perturbed. ‘Everyone has some.’

‘In your novel, perhaps.’

‘Well, this is certainly stranger than fiction,’ Laclos said. ‘Are you telling me the man is not in want of funds? Of a job? Of a woman?’

‘I don’t know anything about his bank account. If he wants a woman, I should think he can get one for himself.’

‘Or perhaps – well now, you’ve known each other for a long time, haven’t you? He isn’t perhaps otherwise inclined?’

‘Oh no. Good God.’ Camille put his cup down. ‘Absolutely not.’

‘Yes, I agree it’s difficult to imagine,’ Laclos said. He frowned. He was good at imagining what went on in other people’s beds – after all, it was his stock-in-trade. Yet the deputy from Artois had a curious innocence about him. Laclos could only imagine that when he was in bed, he slept. ‘Leave it for now,’ he said. ‘It sounds as if M. Robespierre is more trouble than he’s worth. Tell me about Legendre, this butcher – they tell me the man will say anything, and has a formidable pair of lungs.’

‘I wouldn’t have thought he was in the Duke’s class. He must be desperate.’

Laclos pictured the Duke’s bland, perpetually inattentive face. ‘Desperate times, my dear,’ he said with a smile.

‘If you want someone in the Cordeliers district, there is someone much much better than Legendre. Someone with a trained pair of lungs.’

‘You mean Georges d’Anton. Yes, I have him on file. He is the King’s Councillor who refused a good post under Barentin last year. Strange that you should recommend to me someone who recommends himself to Barentin. He turned down another offer later – oh, didn’t he tell you? You should be omniscient, like me. Well – what about him?’

‘He knows everybody in the district. He is an extremely articulate man, he has a very forceful personality. His opinions are – not extreme. He could be persuaded to channel them.’

Laclos looked up. ‘You do think well of him, I see.’

Camille blushed as if he had been detected in a petty deception. Laclos looked at him with his knowing blue eyes, his head tilted to one side. ‘I recollect d’Anton. Great ugly brute of a man. A sort of poor man’s Mirabeau, isn’t he? Really, Camille, why do you have such peculiar taste?’

‘I can’t answer all your questions at once, Laclos. Maître d’Anton is in debt.’

Laclos smiled a simple pleased smile, as if a weight had been taken off his mind. It was one of his operating principles that a man in debt could be seduced by quite small amounts, while a man who was comfortably-off must be tempted by sums that gave his avarice a new dimension. The Duke’s coffers were well-supplied, and indeed he had recently been offered a token of good will by the Prussian Ambassador, whose King was always anxious to upset a French reigning monarch. Still, his cash was not inexhaustible; it amused Laclos to make small economies. He considered d’Anton with guarded interest. ‘How much for his good will?’

‘I’ll negotiate for you,’ Camille said with alacrity. ‘Most people would want a commission, but in this case I’ll forgo it as a mark of my esteem for the Duke.’

‘You’re very cocksure,’ Laclos said, needled. ‘I’m not paying out unless I know he’s safe.’

‘But we’re all corruptible, aren’t we? Or so you say. Listen, Laclos, move now, before the situation is taken out of your hands. If the court comes to its senses and starts to pay out, your friends will desert you by the score.’

‘Let me say,’ Laclos remarked, ‘that it does appear that you are less than wholly devoted to the Duke’s interests yourself.’

‘Some of us were discussing what plans you might have, afterwards, for the less-than-wholly-devoted.’

Camille waited. Laclos thought, how about a one-way ticket to Pennsylvania? You’d enjoy life among the Quakers. Alternatively, how about a nice dip in the Seine? He said, ‘You stick with the Duke, my boy. I promise you’ll do well out of it.’

‘Oh, you can be sure I’ll do well out of it.’ Camille leaned back in his chair. ‘Has it ever occurred to you, Laclos, that you might be helping me to my revolution, and not vice versa? It might be like one of those novels where the characters take over and leave the author behind.’

Laclos brought his fist down on the table and raised his voice. ‘You always want to push it, don’t you?’ he said. ‘You always want to have the last word?’

‘Laclos,’ Camille said, ‘everyone is looking at you.’ It was now impossible to go on. Laclos apologized as they parted. He was annoyed with himself for having lost his temper with a cheap pamphleteer, and the apology was his penance. As he walked he composed his face to its usual urbanity. Camille watched him go. This won’t do, he thought. If this goes on I’ll have no soul to sell when someone makes me a really fair offer. He hurried away, to break to d’Anton the excellent news that he was about to be offered a bribe.

JULY 11: Camille turned up at Robespierre’s lodgings at Versailles. ‘Mirabeau has told the King to pull his troops out of Paris,’ he said. ‘Louis won’t; but those troops are not to be relied on. The Queen’s cabal is trying to get M. Necker sacked. And now the King says he will send the Assembly to the provinces.’

Robespierre was writing a letter to Augustin and Charlotte. He looked up. ‘The Estates-General is what he still calls it.’

‘Yes. So I came to see if you were packing your bags.’

‘Far from it. I’m just settling in.’

Camille wandered about the room. ‘You’re very calm.’

‘I’m learning patience through listening to the Assembly’s daily ration of drivel.’

‘Oh, you don’t think much of your colleagues. Mirabeau – you hate him.’

‘Don’t overstate my case for me.’ Robespierre put his pen down. ‘Camille, come here, let me look at you.’

‘No, why?’ Camille said nervously. ‘Max, tell me what I should do. My opinions will go soft. The republic – the Comte laughs at it. He makes me write, he tells me what to write, and he hardly lets me out of his sight. I sit beside him each night at dinner. The food is good, so is the wine, so is the conversation.’ He threw his hands out. ‘He’s corrupting me.’

‘Don’t be such a prig,’ Robespierre said unexpectedly. ‘He can get you on in the world, and that’s what you need at the moment. You should be there, not here. I can’t give you what he can.’

Robespierre knows – he almost always knows – exactly what will happen. Camille is sharp and clever, but he gives no evidence of any ideas about self-preservation. He has seen Mirabeau with him in public, one arm draped around his shoulders, as if he were some tart he’d picked up at the Palais-Royal. All this is distasteful; and the Comte’s larger motives, his wider ambitions, are as clear as if Dr Guillotin had him on a dissecting table. For the moment, Camille is enjoying himself. The Comte is bringing on his talents. He enjoys the flattery and fuss; then he comes for absolution. Their relationship has fallen back into its old pattern, as if the last decade were the flick of an eyelid. He knows all about the disillusionment that Camille will suffer one day, but there’s no point in trying to tell him: let him live through it. It’s like disappointments in love. Everyone must have them. Or so he is told.

‘Did I tell you about Anaïs, this girl I’m supposed to be engaged to? Augustin tells me I suddenly have rivals.’

‘What, since you left?’

‘So it seems. Hardly repining, is she?’

‘Do you feel hurt?’

He considered. ‘Oh, well, you know, I have always been vastly full of amour propre, haven’t I? No…’ He smiled. ‘She’s a nice girl, Anaïs, but she’s not over-bright. The truth is, it was all set up by other people anyway.’

‘Why did you go along with it?’

‘For the sake of a quiet life.’

Camille wandered across the room. He opened the window a little wider, and leaned out. ‘What’s going to happen?’ he asked. ‘Revolution is inevitable.’

‘Oh yes. But God works through men.’

‘And so?’

‘Somebody must break the deadlock between the Assembly and the King.’

‘But in the real world, of real actions?’

‘And it must be Mirabeau, I suppose. All right, nobody trusts him, but if he gave the signal – ’