По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

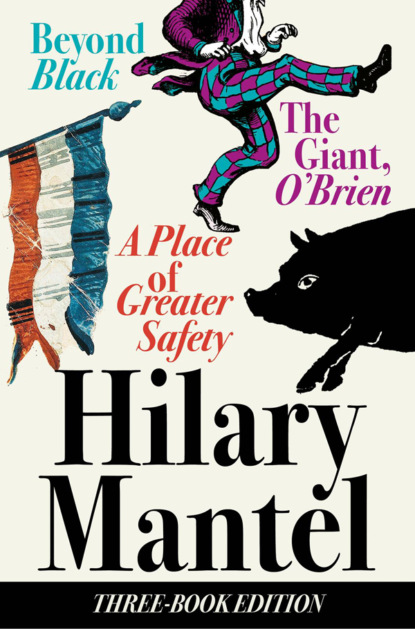

Three-Book Edition: A Place of Greater Safety; Beyond Black; The Giant O’Brien

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

M. Danton had been clerk to one of the local courts. There was a little money, some houses, some land. Madame found herself coping. She was a bossy little woman who approached life with her elbows out. Her sisters’ husbands came by every Sunday, and gave her advice.

Subsequently, the children ran wild. They broke people’s fences and chased sheep and committed various other rural nuisances. When accosted, they talked back. Children of other families they threw in the river.

‘That girls should be like that!’ said M. Camus, Madame’s brother.

‘It isn’t the girls,’ Madame said. ‘It’s Georges-Jacques. But look, they have to survive.’

‘But this is not some jungle,’ M. Camus said. ‘It is not Patagonia. It is Arcis-sur-Aube.’

Arcis is green; the land around is flat and yellow. Life goes on at a steady pace. M. Camus eyes the child, where outside the window he throws stones at the barn.

‘The boy is savage and quite unnecessarily large,’ he says. ‘Why has he got a bandage round his head?’

‘Why should I tell you? You’ll only bad-mouth him.’

Two days ago, one of the girls had brought him home in the early warm dusk. They had been in the bull’s field, she said, playing at Early Christians. This was perhaps the pious gloss Anne Madeleine put on the matter; it was possible of course that not all the Church’s martyrs agreed to be gored, and that some, like Georges-Jacques, went armed with pointed sticks. Half his face was ripped up from the bull’s horn. Panic-stricken, his mother had taken his head in her hands and shoved the flesh together and hoped against hope it would stick. She bandaged it tightly and put another bandage around his head to cover the bumps and cuts on his forehead. For two days, with a helmeted, aggressive air, he stayed in the house and moped. He complained that he had a headache. This was the third day.

Twenty-four hours after M. Camus had taken his leave, Mme Danton stood at the same window and watched – as if in a dazed, dreadful repeating dream – while her son’s remains were manhandled across the fields. A farm labourer carried the heavy body in his arms; she could see how his knees bent under the dead-weight. There were two dogs running after him with their tails between their legs; trailing behind came Anne Madeleine, bawling with rage and despair.

When she reached them she saw that the man had tears in his eyes. ‘That bloody bull will have to be slaughtered,’ he said. They went into the kitchen. There was blood everywhere. It was all over the man’s shirt, the dogs’ fur, Anne Madeleine’s apron and even her hair. It went all over the floor. She cast around for something – a blanket, a clean cloth – on which to lay the corpse of her only son. The labourer, exhausted, swayed against the wall, marking the plaster with a long rust-coloured streak.

‘Put him on the floor,’ she said.

When his cheek touched the cold tiles of the floor, the child moaned softly; only then did she realize he wasn’t dead. Anne Madeleine was repeating the De profundis in a monotone: ‘From the morning watch even until night: let Israel hope in the Lord.’ Her mother hit her across the ear to shut her up. Then a chicken flew in at the door and got on her foot.

‘Don’t strike the girl,’ the labourer said. ‘She pulled him out from under its feet.’

Georges-Jacques opened his eyes and vomited. They made him lie still, and felt his limbs for fractures. His nose was broken. He breathed bubbles of blood. ‘Don’t blow your nose,’ the man said, ‘or your brains will drop out.’

‘Lie still, Georges-Jacques,’ Anne Madeleine said. ‘You gave that bull something to think about. He’ll run and hide when he sees you again.’

His mother said, ‘I wish I had a husband.’

NO ONE HAD LOOKED at his nose much before the incident, so no one could say whether a noble feature had been impaired. But the place scarred badly where the bull’s horn had ripped up his face. The line of damage ran down the side of his cheek, and intruded a purple-brown spur into his upper lip.

The next year he caught smallpox. So did the girls; as it happened, none of them died. His mother did not think that the marks detracted from him. If you are going to be ugly it is as well to be whole-hearted about it, put some effort in. Georges turned heads.

When he was ten years old his mother married again. He was Jean Recordain, a merchant from the town; he was a widower, with one (quiet) boy to bring up. He had a few little eccentricities, but she thought they would do very well together. Georges went to school, a small local affair. He soon found that he could learn anything without the least trouble, so he did not allow school to impinge on his life. One day he was walked on by a herd of pigs. Cuts and bruises resulted, another scar or two hidden by his thick wiry hair.

‘That’s positively the last time I’ll be trampled on by any animal,’ he said. ‘Four-legged or two-legged.’

‘Please God it may be,’ his stepfather said piously.

A YEAR PASSED. One day he collapsed suddenly, with a burning fever, chattering teeth. He coughed sputum stained with blood, and a scraping, crackling noise came from his chest, quite audible to anyone in the room. ‘Lungs possibly not too good,’ the leech said. ‘All those ribs driven into them at frequent intervals. Sorry, my dear. Better fetch the priest.’

The priest came. He gave him the last rites. But the boy failed to die that night. Three days later he still clung to a comatose half-life. His sister Marie-Cécile organized a cycle of prayers; she took the hardest shift, two o’clock in the morning till dawn. The parlour filled up with relations, sitting around trying to say the right thing. There were yawning silences, broken by the desperate sound of everyone speaking at once. News of each breath was relayed from room to room.

On the fourth day he sat up, recognized his family. On the fifth day he cracked jokes, and demanded food in quantity.

He was pronounced out of danger.

They had planned to open the grave, and bury him beside his father. The coffin, which they had put in an outhouse, had to be sent back. Luckily, they had only put a deposit on it.

When Georges-Jacques was convalescent, his stepfather made an expedition to Troyes. Upon his return, he announced that he had found the boy a place in the minor seminary.

‘You dolt,’ his wife said. ‘Confess it, you just want him out of the house.’

‘How can I give my time to my inventions?’ Recordain asked reasonably. ‘I’m living on a battlefield. If it’s not stamping pigs it’s crackling lungs. Who else goes in the river in November? Who else goes in it at all? People in Arcis have no need to know how to swim. The boy’s above himself.’

‘Perhaps he could be a priest, after all,’ Madame said, conciliatory.

‘Oh yes,’ Uncle Camus said. ‘I can just see him ministering to his flock. Perhaps they’ll send him on a Crusade.’

‘I don’t know where he gets his brains from,’ Madame said. ‘There’s no brains in the family.’

‘Thanks,’ her brother said.

‘Of course, just because he goes to the seminary it doesn’t mean he has to be a priest. There’s the law. We’ve got law in the family.’

‘And if he disliked the verdict? The mind recoils.’

‘Anyway,’ Madame said, ‘let me keep him at home for a year or two, Jean. He’s my only son. He’s a comfort to me.’

‘Whatever makes you happy,’ Jean Recordain said. He was a mild, easy-going man who pleased his wife by doing exactly as she told him; much of his time nowadays he spent in an outlying farm building where he was inventing a machine for spinning cotton. He said it would change the world.

His stepson was fourteen years old when he removed his noisy and overgrown presence to the ancient cathedral city of Troyes. Troyes was an orderly town. The livestock had a sense of its lowly place in the universe, and the Fathers did not allow swimming. There seemed an outside chance that he would survive.

Later, when he looked back on his childhood, he always described it as extraordinarily happy.

IN A THINNER, greyer, more northerly light, a wedding is celebrated. It is 2 January, and the sparse, cold congregation are able to wish each other the compliments of the season.

Jacqueline Carraut’s love affair occupied the spring and summer of 1757, and by Michaelmas she knew she was pregnant. She never made mistakes. Or only big ones, she thought.

Because her lover had now cooled towards her, because her father was a choleric man, she let out the bodices of her dresses, and kept herself very quietly. When she sat at her father’s table and could not eat, she shovelled the food down to the terrier who sat by her skirts. Advent came.

‘If you had told me earlier,’ her lover said, ‘we would have only had the row about a brewer’s daughter marrying into the de Robespierre family. But now, the way you’re swelling up, we have a scandal as well.’

‘A love child,’ Jacqueline said. She was not romantic by nature, but she felt the posture forced upon her. She held up her chin as she stood at the altar, and looked the family in the eye all day. Her own family, that is; the de Robespierre family stayed at home.

François was twenty-six years old. He was the rising star of the local barrister’s association and one of the district’s most coveted bachelors. The de Robespierre family had been in the Arras district for three hundred years. They had no money, and they were very proud. Jacqueline was amazed by the household into which she was received. In her father’s house, where the brewer ranted all day and bawled his workers out, great joints of meat were put upon the table. The de Robespierres were polite to each other, and ate thin soup.

Thinking of her, as they did, as a robust, common sort of girl, they ladled huge watery platefuls in her direction. They even offered her father’s beer. But Jacqueline was not robust. She was sick and frail. A good thing she had married into gentility, people said spitefully. There was no work to be got out of her. She was just a little china ornament, a piece of porcelain, her narrow shape distorted by the coming child.

François had stood before the priest and done his duty; but once he met her body between the sheets, he felt again the original, visceral passion. He was drawn to the new heart that beat in her side, to the primitive curve of her ribs. He was awed by her translucent skin, by the skin inside her wrists which showed greenish marble veins. He was drawn by her myopic green eyes, wide-open eyes that could soften or sharpen like the eyes of a cat. When she spoke, her phrases were like little claws, sinking in.

‘They have that salty soup in their veins,’ she said. ‘If you cut them, they would bleed good manners. Tomorrow, thank God, we shall be in our own house.’

It was an embarrassed, embattled winter. François’s two sisters hovered about, taking messages and being afraid of saying too much. Jacqueline’s child, a boy, was born on 6 May, at two in the morning. Later that day, the family met at the font. François’s father stood godparent, so the baby was named after him, Maximilien. It was a good, old, family name, he told Jacqueline’s mother; it was a good, old family to which her daughter now belonged.