По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

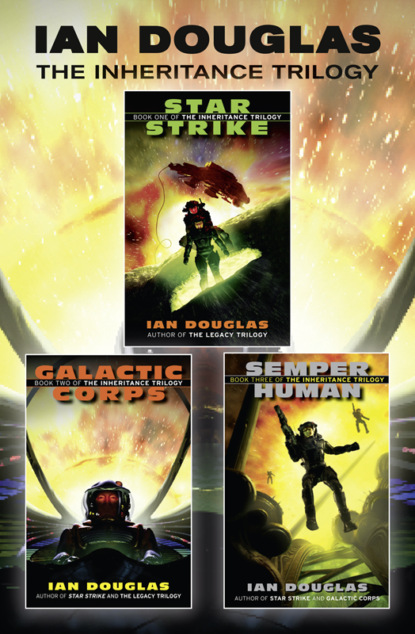

The Complete Inheritance Trilogy: Star Strike, Galactic Corps, Semper Human

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgments (#ulink_d965179a-e76e-5184-8ae4-a5c4f08983c5)

My special thanks to David Plottel, friend, programmer, mathematician, and ubergeek, for his insights into Leonhard Euler and the God-equation known as Euler’s Identity.

Keep it simple. Secure the spaceport. Hold until relieved.

Nothing new there.

Remember your training.

The question was whether the landings would be enough. Alighan was a heavily populated world in the Theocracy of Islam, with over two billion people in the ocean-girdled world’s teeming cities. The Marine assault force consisted of the four companies of the 55th Marine Aerospace Regimental Strikeforce, a total of five hundred eighty men and women … against an entire world.

True, they were exceptionally well armed and armored men and women, and they seemed—for the moment at least—to have the element of surprise. Even so, fewer than six hundred Marines against a population of two billion who would fight to the death and take as many Marines with them as they could.

Impossible.

Ridiculously impossible.

But the United Star Marines specialized in the impossible, as they and their predecessors had done for the past eleven hundred years …

Prologue (#ulink_ce2f18e1-a654-57b7-9127-b48ade547351)

Deep within the star clouds of the Second Galactic Spiral Arm, a sentient machine detected the blue-white shriek of tortured hydrogen atoms, and a program hundreds of thousands of years ancient switched from stand-by to active. Something was out there … something massive, something moving at very nearly the speed of light.

Even the hardest interstellar vacuum contains isolated flecks of matter—hydrogen atoms, mostly, perhaps one per cubic centimeter or so. The object’s high-speed passage plowed through these atoms, ionizing many, leaving a boiling hiss in its wake easily detectable by appropriately sensitive instrumentation. The disturbance was a kind of wake, created by a mass of some hundreds of millions of tons plowing through the tenuous matter of the interstellar void at near-c.

The sentry machine had taken up its lonely vigil half a million years before, during the desperate and no-quarter war of extermination against the Associative, a war that had laid waste to ten thousand suns and countless worlds scattered across a third of the Galaxy. Occasionally, it conversed with others of its kind—a means of staying sane through the millennia—but for most of its existence it had been asleep, dreaming the eldritch dreams of a being neither wholly mechanism, nor wholly biological.

The builders of the Sentry called themselves something that might have translated, very approximately, as “We Who Are.” Other species across light centuries of space and hundreds of millennia called them many other things. The inhabitants of Earth, once, had called them “Xul,” a name that in ancient Sumeria had come to mean “demon.”

A far older civilization had called them the Hunters of the Dawn.

However they were known to themselves or to others, how they were identified was less important for their view of themselves than was their evolutionary imperative, the drive, refined over millions of years, that made them what they were. For the Xul, existence—more, survival—was an absolute, the defining characteristic of their universe. In their worldview, survival meant eliminating all potential competition. Their culture did not have anything like religion, but if it had, their religion would have been a kind of Darwinian dogmatism, with the fact that they had so far survived serving as proof that they were, indeed, the fittest.

For the Xul, the first requirement for continued survival was the detection and identification of potential threats to existence. An object with the mass of a fair-sized asteroid traveling through the Galaxy at near-c velocities indicated both sentience and a technology that might represent a serious threat.

With an analytical detachment more characteristic of the computers in its ancestry than of organic beings, the Sentry tracked the disturbance through local space. A ripple twisted the fabric of space/time, and the Sentry shifted across light-years, emerging alongside the massive object, traveling at precisely the object’s velocity.

At this speed, a hair’s breadth short of the speed of light itself, the universe appeared weirdly and beautifully compressed, a ring of solid starlight encircling the heavens slightly ahead of the hurtling vessels. With the patient calm of a lifespan measured in millennia, the Sentry reached out with myriad senses, tasting the anomalous traveler.

Outwardly, the object was an ordinary asteroid, a carbonaceous chondrite of fairly typical composition, with a dusty, pocked surface of such a dark gray color as to be nearly coal black. Outwardly, there was no indication of intelligent design—no lights, no artificial structures on the surface, no thruster venturis or other obvious clues to the object’s propulsive system. Even the high velocity might be an artifact … a souvenir of a long-ago close-passage of a black hole or neutron star, with the resultant slingshot effect whipping a random, dead rock to within one percent of c.

But the Sentry’s gentle probings elicited other evidence, proof that the fast-moving object was both the product of technology and inhabited. A steady trickle of neutrinos proved the presence of hydrogen fusion plants, providing power for life-support and secondary systems. The tick and flux of even more subtle, virtual particles revealed the operation of a quantum effect power system, tapping the base state of space itself for the energies necessary to move that much mass at that high a speed. The drive was quiescent now, but the potential remained, a subtle aura of shifting energies representing fields and forces that might engage at any moment. Perhaps most telling of all, a powerful shield composed of interplaying gravitic and magnetic fields swept space far ahead of the starship—for starship is what the object was—clearing its path of stray subatomic particles lest they strike rock and cascade into deadly secondary radiation, frying the ship’s passengers as they slept away the objective decades.

For passengers there were—some fifty thousand of them, stored in a cybernetic hibernation that let them pass decades of subjective time without the need for millions of tons of food, water, and other expendables. At the moment, the only member of the starship’s crew that was actually awake was a being far more closely related, in its basic nature, to the Sentry than it was to the slumbering beings in its care, a sentient computer program named Perseus.

For over five hundred years, Perseus had overseen the routine operation of the asteroid starship and her refugee passengers, monitoring drive systems and power plant, life support and cybe-hibe stasis capsules. The ship, christened Argo, had fled distant Earth a few years after the devastating attack on that world by the Xul; her destination was another galaxy entirely, M-31, in Andromeda, something over two million light-years distant.

The voyage as planned would take almost 2.3 million years objective, but on board the clocks would record the passage of barely thirty years. Argo’s sleeping passengers, for the most part, were members of Earth’s political and economic elite. Many were representatives of the governments of the United States and of the American Union who’d felt Humankind’s only hope of survival lay in avoiding all-out war with the technologically advanced Xul, in escaping the enemy’s notice, in fleeing to another galaxy entirely and beginning anew.

Their decision proved to be a supreme exercise in wishful thinking. The Xul sentry engaged Perseus as the sentient program was still shifting to full operational mode. It had time to engage a single emergency comm channel before the Xul group-mind overwhelmed it in an electronic cascade of incoming data.

Parts of Perseus were hijacked by the alien operating system; others were wiped away, or simply stored for later exploration.

And within the Argo-planetoid’s heart, fifty thousand human minds cried out as one as they were patterned and replicated by the intruder. Moments later, the asteroid’s immense kinetic energy was instantly transformed into heat and light, bathing the Xul Sentry in the actinic glare of a tiny nova.

By the Xul way of thinking, the asteroid starship represented both a threat and unfinished business.

Neither could be tolerated.

1 (#ulink_9bfe3d7c-c7a6-5b72-9427-b93ad4979578)

0407.1102

Green 1, 1-1 Bravo

Alighan

0340/38:22 hours, local time

The Specters descended over the Southern Sea, slicing north through turbulent air, their hulls phase-shifted so that they were not entirely within the embrace of normal space. Shifted, they were all but invisible to radar, and little more than shadows to human eyes, shadows flickering across a star-clotted night.

On board Specter One-one Bravo, Gunnery Sergeant Charel Ramsey sat huddled pauldron-to-pauldron with the Marines locked in to either side of him. The squad bay was red lit and crowded, a narrow space barely large enough to accommodate a platoon of forty-eight Marines in full Mark 660 assault battlesuits. He tried once again to access the tacnet, and bit off a curse when all that showed within the open mindwindow was static. They were going in blind, hot and blind, and he didn’t like the feeling. If the Muzzies got twitchy and started painting their southern sky with plasma bolts or A.M. needlers, phase-shifting would not protect them in the least.

“They’re holding off on the drones,” Master Sergeant Adellen said over the tac channel, almost as if she were reading his mind. Likely she was as nervous as the rest of the Marines in the Specter’s belly. She just hid it better than most. “They don’t want to tip the grounders off that we’re on final.”

“Yeah, but it would be nice to see where the hell we’re going,” Corporal Takamura observed. “We can’t see shit through the LV’s optics.”

That was not entirely true, of course. Ramsey had a window open in his mind linked through to the feed from the Specter’s cockpit. Menu selections gave him a choice of views—through cameras forward or aft, in visible light, lowlight, or infrared, or a computer-generated map of the planet that showed twelve green triangles in a double-chevron formation moving toward the still-distant coastline. Ramsey had settled on the map view, since the various optical feeds showed little now but water, clouds, and stars.

The MLV-44 Specter Marine Landing Vehicles were large and slow, with gull wings and fusion thrusters that gave them somewhat more maneuverability than a falling brick, but not much. Each mounted a pair of AI-controlled high-speed cannon firing contained micro-antimatter rounds as defense against incoming missiles, but they relied on stealth and surprise for survival, not firepower, and certainly not armor. A Specter’s hull could shield those on board from the searing heat of atmospheric entry, but a mag-driven needle or even a stray chunk of high-energy shrapnel could puncture its variform shell with shocking ease. Ramsey had seen the results of shrapnel impact on a grounded Specter before, on Shamsheer and on New Tariq.

The Specter jolted hard, suddenly and unexpectedly, and someone vented a sharp curse. They were falling into denser air, passing through the cloud deck, and things were getting rougher.

“One more of those,” Sergeant Vallida said, her voice bitter, “and Private Dowers gets jettisoned.”

“Hey, Sarge! I didn’t do anything!”

“Don’t pick on Dowers,” Adellen said. “He didn’t know.”

“Yeah, but he should have. Fucking nectricots. …”

It was rank superstition, of course. Even if it went back over a thousand years. Maybe it was the sheer age of the tradition that gave it so much power. But somehow, back in the twentieth or twenty-first century, it had become an article of faith that if a Marine ate the apricots in his ration pack before boarding an alligator or other armored transport, the vehicle would break down. Over the centuries, the focus of the curse had gradually shifted from apricots to genegineered nectricots, but the principle remained the same.

And Ela Vallida had walked in on Dowers back on board the Kelley just before the platoon had saddled up that morning, to find him happily slurping down the last of the nectricots in his drop rats. Dowers was a fungie, fresh out of RTC, and not yet fully conversant with the bewildering labyrinth of tradition and history within which every Marine walked.

“Fucking fungie,” Vallida added.