По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

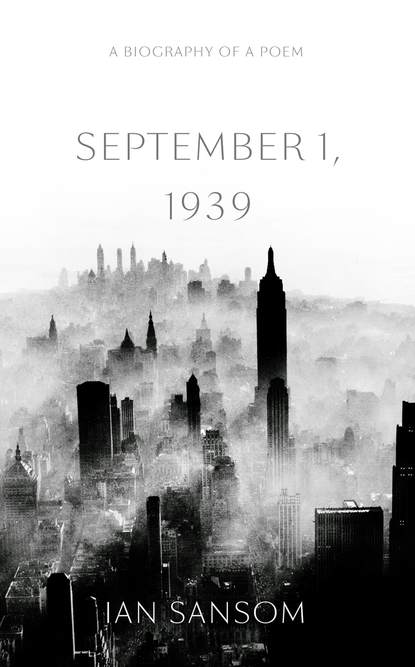

September 1, 1939: A Biography of a Poem

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

(Philip Roth describes the urge to live on paper in his novel Exit Ghost: ‘Isn’t one’s pain quotient shocking enough without fictional amplification, without giving things an intensity that is ephemeral in life and sometimes even unseen? Not for some. For some very, very few that amplification, evolving uncertainly out of nothing, constitutes their only assurance, and the unlived, the surmise, fully drawn in print on paper, is the life whose meaning comes to matter most.’ To write is to live the unlived.)

To write is to reveal oneself.

*

It is also a wonderful disguise. Poets, like all other writers, are liars, confabulators and cheats – just read a biography of a poet. Any poet. They’re all the same: poets are self-pleasuring beings who like to play around with their ‘I’, just as they like to play around with everything else.

*

With his ‘I’ at the beginning of this poem, Auden is donning a disguise. He is putting on a mask.

*

In middle age his face indeed became a mask – a ‘wedding cake left out in the rain’ is how he liked to describe it. He looked, he said, like ‘an unmade bed’. That face, that ruined, piteous, covetable, comfortable face – ‘I have a face of putty,’ he told Stephen Spender, ‘I should have been a clown’ – has long been a source of fascination to writers and artists. The philosopher Hannah Arendt remarked that it was ‘as though life itself had delineated a kind of face-scape to make manifest the “heart’s invisible furies”’. (Humboldt, in Saul Bellow’s Humboldt’s Gift, is described as having ‘developed in his face all the graver, all the more important human feelings’. Wouldn’t you just love a face, like Auden’s, like Humboldt’s, in which you had developed all the more important human feelings?) According to Randall Jarrell, Auden looked ‘like a disenchanted lion’. The poet Gavin Ewart charted his appalled fascination with Auden’s face – what another poet, John Hollander, calls simply ‘The Face’ – in a poem titled ‘Auden’:

Photographed, he looked like Spencer Tracy

or even Danny Kaye –

in the late Forties. But later it was wiser

to look the other way.

A young David Hockney, asked to sketch a portrait of Auden, was absolutely horrified: ‘I kept thinking, if his face looks like this, what must his balls look like?’

*

Whatever it looks like, whatever it appears to be, perhaps all we can be sure of is that the ‘I’ in the work of a poet is a complex act of self-dramatisation, a performance. The ‘I’ in a poem may appear to be referring to something – to someone – but we need not postulate the poet’s self as its referent. The ‘I’ in a poem is not necessarily a proxy for a name.

The I ≠ Auden.

*

I ≠ A.

*

‘I’ is a persona. Though the persona may of course be Auden: it may be a clever double bluff; ‘I’ am I; either I am the mask, or the mask has eaten into the face, the performance having become the true self. Henry David Thoreau, at the beginning of Walden, reminds his readers that even when the ‘I’ appears to be absent it’s always there, hiding: ‘In most books, the I, or first person, is omitted; in this it will be retained; that, in respect to egotism, is the main difference. We commonly do not remember that it is, after all, always the first person that is speaking.’

Writers are always hiding in plain sight.

Madame Bovary, c’est moi.

*

(A couple of years ago I published a book of short stories. Everyone assumed they were autobiographical. Some were autobiographical. But not the ones that people thought.)

*

Whether we know it or not, we bring great expectations to a poem: we are conditioned to expect something from a poem, as soon as it declares itself a poem, and even more so when an ‘I’ declares itself at the beginning of a poem. A poetic ‘I’ implies a particular kind of poem, a lyric poem, the kind of poem we are familiar with from school, a poem which usually promises and delivers intense personal emotions presented in the first person. M. H. Abrams, who was one of those literary critics everyone used to read and now almost no one has heard of – the fate of all critics – defined the Romantic lyric poem as a meditation that ‘achieves an insight, faces up to a tragic loss, comes to a moral decision, or resolves an emotional problem’. This is the kind of poem we know what to do with.

So what are we going to get here, in ‘September 1, 1939’? An insight? A reckoning? A decision? A resolution?

*

In ‘September 1, 1939’ we get all of that, and more – which is exactly the trouble, and what Auden hated about the poem, which he described as ‘the most dishonest’ he had ever written.

*

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves. Let’s just assume for a moment – as we naturally do – that the ‘I’ here is an unproblematic person, that the ‘I’ here is Auden.

Fine.

*

Who the hell is W. H. Auden?

The Modern Poet (#litres_trial_promo)

‘It’s odd to be asked today what I saw in Auden,’ replied the American poet John Ashbery to a wet-behind-the-ears interviewer in 1980. ‘Forty years ago when I first began to read modern poetry no one would have asked – he was the modern poet.’

*

In his 1937 ‘Letter to W. H. Auden’, the poet Louis MacNeice addressed his friend, ‘Dear Wystan, I have to write you a letter in a great hurry and so it would be out of the question to try to assess your importance. I take it that you are important.’

*

He was more than important: he was an absolute star. In his book The Personal Principle (1944), the literary critic D. S. Savage claimed that during the 1930s Auden was ‘the centre of a cult’ and, in a telling phrase, described Auden’s position thus: ‘A new star had arisen, it seemed, in the English sky.’ John Berryman recalled that even in America ‘by 1935 … the Auden climate had set in strongly’. What Tom Driberg in the Daily Express called ‘awareness of Auden’ was everywhere: it affected things generally; as Boswell breathed the Johnsonian ‘oether’, so the 1930s breathed the air of Auden. When the London Mercury was published for the last time on the eve of the Second World War, Stephen Spender summed things up in an article titled ‘The Importance of W. H. Auden’: ‘Auden’s poetry is a phenomenon, the most remarkable in English verse of this decade.’

*

Now, to be clear: not everyone admired Auden. Some people despised him. Hugh MacDiarmid thought him a ‘complete wash-out’. Truman Capote, when asked what he thought of Auden’s poetry, replied, ‘Never meant nothin’ to me.’ (Though – note – even MacDiarmid, in his polemical autobiographical prose work Lucky Poet (1943), attempting to define ‘The Kind of Poetry I Want’, had to devote much of his time to defining ‘the kind of poetry I don’t want’, i.e. ‘the Auden–Spender–MacNeice school’.) The argument against Auden is certainly worth stating and goes something like this:

‘W. H. Auden is to blame for everything that went wrong with English poetry in the late twentieth century. Absurdly overpraised when young, he remained naive and immature both as a person and as a poet, his preciosities and youthful good looks becoming vile and monstrous. He was dictatorial in his approach and his opinions, imprisoned by his own intelligence, intellectually dishonest, irresponsible and incoherent, atrociously showy in diction and lexical range, technically ingenious rather than profound, pathetically at the mercy of contemporary cultural and political fashions and ideas, facetious, frivolous, self-praising, self-indulgent, vulgar and ultimately merely quaint: the ruined schoolboy; an example, indeed the ultimate example, the epitome, the exemplum, not of mastery but of Englishness metastasised. Auden undoubtedly thought he was it and the next big thing, when in fact he was It: the disease, the enemy, The Thing.’

*

This sort of argument has been thoroughly rehearsed down through the years by readers such as F. R. Leavis, and Randall Jarrell (during the hate phase of his love–hate relationship), and Philip Larkin (ditto), and Hugh MacDiarmid, and William Empson. One would perhaps expect all of them to complain – they were world-class complainers – but when someone like Seamus Heaney, that Seamus Heaney, the Seamus Heaney, a poet and critic with perfect manners, whose kindness and generosity knew almost no bounds, when even Seamus Heaney, in a review of Auden’s Collected Poems, writes dismissively of Auden’s ‘educated in-talk’ and of his tone ‘somewhere between camp and costive’, one might begin to think that there is indeed a serious case to be made against him. Maybe Auden was just a coterie poet; maybe he was just a flash in the pan; a poet merely of his class and his place and his time. William Empson has a poem, ‘Just a Smack at Auden’, which is certainly very funny, mocking Auden’s 1930s doom-mongering (‘Treason of the clerks, boys, curtains that descend, / Lights becoming darks, boys, waiting for the end’), but Heaney’s summation of Auden’s achievement as ‘a writer of perfect light verse’ is potentially more wounding.

(We may well return to the question of ‘light’ verse later. But an obvious question has to be, does great literature necessarily have to be ‘heavy’? Does it have to be serious and difficult? Does it have to be exhausting and challenging and exceptional? Does every book have to be a pick-axe breaking the frozen sea in our souls? Sometimes it’s nice – isn’t it? – to hear the sound of a swizzle stick tinkling away at the ice.)

*

Anyway, and nonetheless, and despite the quibbles and the doubts, it would be safe to say that in the 1930s, for those whom it affected, the Auden phenomenon was as disturbing as it was remarkable. The title of Geoffrey Grigson’s contribution to the special 1937 New Verse Auden double issue, ‘Auden as a Monster’, is indicative of the fear and excitement generated by Auden’s reputation. ‘Auden does not fit. Auden is no gentleman. Auden does not write, or exist, by any of the codes, by the Bloomsbury rules, by the Hampstead rules, by the Oxford, Cambridge, or the Russell Square rules,’ enthused Grigson; Auden’s poetry, he claimed, had a ‘monstrous’ quality. Other contributors to New Verse were similarly impressed by Auden’s peculiar strength and power: Edwin Muir described Auden’s imagination as ‘grotesque’; Frederic Prokosch described his talents as ‘immense’; Dylan Thomas described him as ‘wide and deep’; Bernard Spencer claimed that he ‘succeeds in brutalizing his thought and language’.

*

Auden was clearly regarded – as great writers often are by their contemporaries – as somehow superhuman, or rather subhuman, inhuman, freakish. (Stephen Spender, in his Journals, recalls being accused of making Auden ‘sound a bit inhuman’: ‘This did ring a bell,’ he writes, ‘because I remember when we were both young thinking of him as sui generis, not at all like other people and of an inhuman cleverness. I did not think of him as having ordinary human feelings.’)