По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

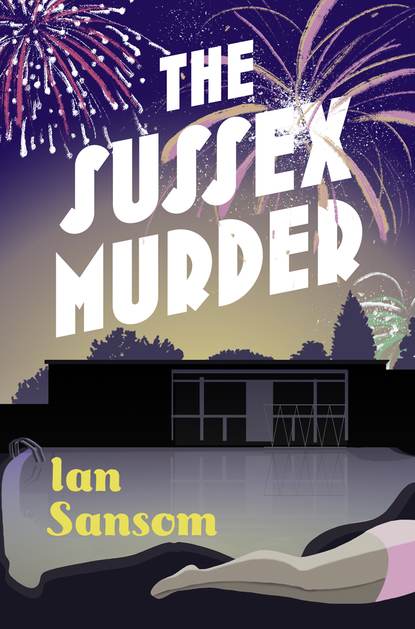

Flaming Sussex

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Not as easy as it sounds, is it?’ said Morley.

‘Indeed,’ I agreed.

‘We’ve not met, have we?’ asked Molly, breaking off from her tongue-twisting but remaining seated among the flowers and fruit and extending her hand.

‘No. I’m Stephen Sefton,’ I said, leaning forward, not entirely sure whether to kiss her hand, shake it, or kneel before her and receive a blessing.

‘Ah, yes, Swanton has told me so much about you,’ said Molly. No one called Morley Swanton.

We shook hands.

‘All of it good, I hope,’ I said.

‘Hardly any of it good,’ Molly said with a laugh. ‘And all the better for that. Can I offer you a drink?’ She indicated some unopened bottles – champagne, wine, lemonade – on the dressing room table.

I looked at Miriam out of the corner of my eye. She gave a sharp, vigorous shake of her head.

‘I won’t, thank you,’ I said. ‘It’s been a long day. Miriam and I have just motored down from London. We should probably retire.’

‘You are clearly as self-disciplined as your famously abstemious employer,’ said Molly.

‘Perhaps not quite,’ I said.

‘You must have something,’ she said. ‘Here.’ She got up, took two bottles of what looked like American lemonade, pushed down the marbles in the two bottle tops simultaneously, one in each hand, and thrust them towards us. ‘A little trick I learned back home.’

‘Flexibility of the lips is very important, you see,’ said Morley, who was still on the subject of tongue-twisters.

‘Oh yes, flexibility of the lips is very important, isn’t it, Miriam?’ said Molly.

‘I have no idea,’ said Miriam, rather huffily.

‘Vowels as well as consonants suffer terribly from a lack of good lip movement,’ said Morley. ‘The lips are part of the resonating system, you see, which is what makes each human voice unique.’ His own voice was as rapid as ever and as strange, rattling like a kettle on the range. ‘The lungs and the diaphragm are the bellows, the larynx the vibrator, and this’ – he tapped a finger to his head – ‘the resonator. Molly has a magnificent resonator, Miriam.’

‘I’m sure she has, Father,’ said Miriam, as Morley and Molly started to make a humming sound together.

Miriam huffed.

Even by the high standards of embarrassment I had become accustomed to while working with Morley and Miriam, it was all rather embarrassing. Morley was clearly as fascinated with Molly as she was intent on fascinating him. They had first met, I later discovered, at a meeting of Morley’s so-called Bonhomie Club, a group of friends whom he brought together once a month in London, for the purposes of discussion, playing chess, and listening to music. Molly had been invited by Morley to give a recital, and the two of them had quickly become inseparable.

‘Your father, Miriam!’ said Molly, breaking her gaze and her hum with Morley. ‘He’s incredible. I mean, his life, his experiences. His capacity for hard work! I’m surprised it doesn’t simply sap all the energy out of him!’

‘Oh, I’m sure you’ll find other ways of sapping the energy out of him.’

‘His knowledge!’

‘A little knowledge is a dangerous thing,’ said Miriam.

‘“A little learning is a dangerous thing,”’ corrected Morley.

‘“Drink deep, or taste not the Pierian spring: There shallow draughts intoxicate the brain,”’ said Miriam.

‘“And drinking largely sobers us again,”’ said Morley, completing the quotation. ‘Sefton?’ he asked.

‘Dryden?’ I suggested.

‘Pope!’ said Morley. ‘Essay on Criticism.’

‘Marvellous!’ said Molly, clapping her gloved hands together. ‘You know, you’re all just so … curious.’

‘That’s one word for it,’ said Miriam.

‘I’m terribly curious myself,’ said Molly.

‘Really?’

‘Oh yes. I married my first husband entirely out of curiosity.’

‘Isn’t one supposed to marry for love?’ said Miriam.

‘One is supposed to do a lot of things, my dear,’ said Molly. ‘Do you know the final trio from Der Rosenkavalier?’

‘Not off the top of my head,’ said Miriam. ‘No.’

‘“Hab mir’s gelobt”,’ said Morley.

‘Indeed,’ said Molly. ‘In which the Marschallin gives up her young lover, Octavian, when she realises that he is in love with Sophie.’

Molly closed her eyes for a moment and then quietly began to sketch out the melody with her – admittedly – extraordinary voice, a soft, clear, luminous soprano. Morley closed his eyes and hummed along.

I thought for a moment that Miriam might actually be physically sick, but fortunately we had the Bedlington with us, who made his presence known at this point by attempting to climb up onto Molly’s lap, interrupting the impromptu recital.

‘Well, well, who is this little fellow?’ Molly said, scooping him up.

‘This is Pablo,’ I said.

‘Pablito, surely,’ said Molly, petting him like a baby.

Miriam snorted derisively.

‘I met Picasso at a dance in Madrid some years ago. Did I ever tell you, Swanton?’

‘I don’t think so, my dear,’ said Morley.

‘Yes. I’d been performing – Teatro de la Zarzuela – and there had been a dinner in my honour and we all went dancing in this wonderful little taverna, and Picasso was there and he really was quite a … bull of a man.’

‘The minotaur of modern art,’ said Morley.

‘Exactly!’ said Molly. ‘The minotaur of modern art! How clever!’