По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

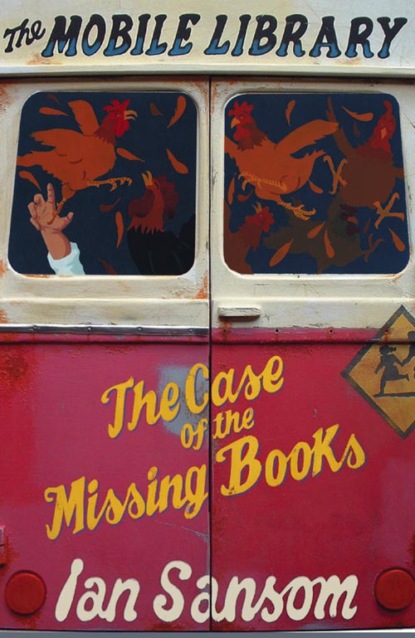

The Case of the Missing Books

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Well. Yes. I shall.’

‘Good.’

‘Today.’

‘Fine.’

‘Immediately.’

‘Good.’

‘Goodnight!’

‘Goodnight to you. And when you’re done with your carrying on,’ shouted George after his retreating figure, ‘if you go on into the house Brownie’ll help get your clothes dried off.’

‘Thank. You!’ said Israel. And he slammed the door of his room – his coop – behind him.

He hated losing his temper. He never usually lost his temper. He never usually had anything to lose his temper about. But this, this place was different: it made you lose your temper.

He surveyed his surroundings: a small broken-down chest of drawers, an old sink plumbed into one corner, attached to the brick wall with wooden battens. The rug on the concrete floor. The big rusty cast-iron bed…

And on the centre of the bed, four chickens, looking at him accusingly.

He slammed back out of the door, past George, who simply pointed at a door in a building on the other side of the farmyard.

Israel walked in.

‘Right!’ he called furiously. ‘Hello! Hello!! Good morning? Anyone about here? Anyone up in this nuthouse?’

He walked through to the kitchen, where there was a young man reading a newspaper, sitting at a scrubbed-pine table next to a dirty white Rayburn solid-fuel stove.

‘Hi,’ the young man said, in a disarmingly friendly manner, as Israel stormed in. ‘You must be Mr Armstrong.’

‘Yes. That’s right.’

‘Pleased to meet you,’ said the young man, holding out his hand towards the sopping wet, brown-corduroy mess of Israel. ‘Nice suit. I’m Brian. But everyone calls me Brownie. Hey, Granda?’ he continued, apparently shouting to a heap of filthy rags piled on a ratty old armchair on the other side of the Rayburn, and which turned out to be a stubbly old man wrapped up in pyjamas and jumpers. ‘This is Mr Armstrong. This is my granda, Israel. Granda, this is the fella who’s going to be staying with us…’

Israel was now regretting his rudeness – old people and polite people can do that to you, if you’re not careful.

‘It’s really very kind of you—’ he began.

The stubbly old man stared at Israel with beady, watery blue eyes for a moment before speaking.

‘Surely, doesn’t the Good Lord tell us that if you entertain a stranger you entertain Me.’

‘Right,’ said Israel. Oh, God.

‘And we’re being paid for it, Granda.’

‘Aye, well.’

‘He’s the librarian, Granda. Do you remember?’

‘He doesn’t look like a librarian. He looks as if he’s the blavers.’

‘Blavers?’ said Israel.

‘Ach, Granda,’ said Brownie scoldingly. ‘Can I get you some coffee, Israel?’

‘Erm, yes, thanks,’ said Israel, disarmed by the boy’s easy-going manner. ‘A cup of coffee would be great.’

‘Espresso? Cappuccino?’

‘Young people today,’ mumbled the old man, to no one in particular.

‘I’ll take an espresso if you have one—’ began Israel.

‘No, I’m joking,’ said Brownie. ‘It’s instant.’

‘Right. Well, whatever.’ He became conscious of his dripping onto the floor. ‘And I…erm. If you don’t mind, while you’re…The lady – erm – George?’

‘Yes.’

‘Right. Yes. George said you’d be able to dry off these clothes for me? They got a bit wet. Out in the farmyard there?’

‘Spot of rain?’

‘Yes,’ said Israel, abashed. ‘You could say that.’

‘No problem. We’ll just put them on the Rayburn here. That’ll do it. And what happened to your eye?’

‘It was just an…accident,’ said Israel, remembering now why his whole head hurt, and why he couldn’t see properly.

‘You’ve a rare ‘un there,’ said Brownie. ‘Should have seen the other fella though, eh?’

‘Yes.’

‘It’s an absolute beauty.’

‘Right.’

‘Like a big ripe plum so it is.’

‘Yes.’

‘Does it hurt?’

‘Yes. Thanks. Well. I’ll just pop and get some spare trousers and what have you.’