По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

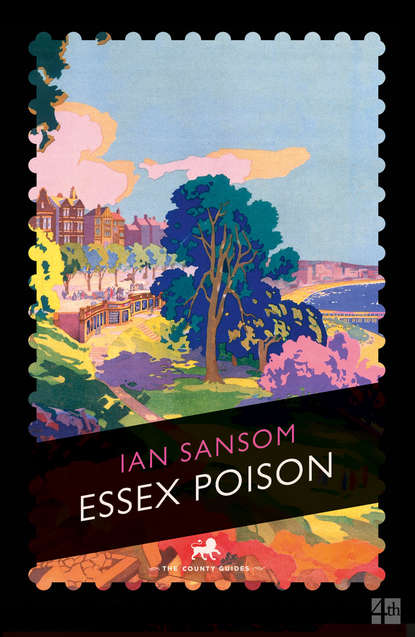

Essex Poison

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

I was about to reply when there came a horrible sharp dinning in my right ear: I wondered for a second if I had perhaps burst an eardrum after my fall down the stairs. I hadn’t: it was just Miriam, with a trumpet to her lips, attempting some sort of reveille.

‘How did you find me?’ I managed to ask them, through my confusion.

‘Really, Sefton. It doesn’t exactly take a Miss Marple to track your movements,’ said Miriam. She laid down the trumpet and was about to pick up a trombone.

‘I’ve got a bit of a headache, actually,’ I said.

‘I’m not surprised. You look dreadful. What on earth’s happened to you? Have you been in another fight?’ I saw that her eyes had alighted upon the xylophone in the corner.

‘Please,’ I said. ‘I really do have a—’

‘Well, if you will insist on drinking and carousing, Sefton, what on earth do you expect?’

‘A most singular method of enjoying oneself, if you don’t mind my saying so,’ added Morley. ‘Not at all good for one. The old ivory dome.’ He tapped a finger to his head. ‘One has to take care of it, you know. I was at Madison Square Garden when Max Baer beat Primo Carnera – goodness me, that was a fight. Couldn’t you take up chess instead? Do you know Max Euwe?’

‘I can’t say I do,’ I said.

‘World champion? Defeated Alekhine?’

‘I must have missed that,’ I said.

‘Good dose of Eno’s Fruit Salts will see you right,’ said Morley.

‘Mmm,’ I agreed.

‘Or this,’ said Miriam, and she thrust her left wrist under my nose. ‘Have a sniff. It’s Schiaparelli’s Shocking. My new scent. Given to me by an admirer. Do you like it?’

I took a quick sniff. It smelled like all other perfume.

‘Well?’ said Miriam.

‘Very nice,’ I said, finally beginning to gain full consciousness.

Miriam and Morley certainly had a way of waking a man up in the morning.

Morley was opposite, at the piano, looking as spruce and as chipper as ever: bow tie, light tweeds, dazzling brogues. Miriam was doing her best to lounge on Ron Pease’s office chair – and her best was more than good enough. She somehow looked at this unearthly hour as she always looked: as though she had just finished a photo-shoot, perhaps for Vogue magazine, or some publicity stills for MGM. Her eye make-up was fashionably smudged, her white dress and matching jacket exquisite. She was also sporting some sort of barbaric necklace that looked as though it might recently have been wrenched from the neck of an aboriginal tribesperson, and then set with diamonds, the sort of necklace that one sometimes sees in the window of Asprey – the sort of necklace that might cost at least one hundred pounds or more.

I put the thought immediately from my mind.

‘Who let you in?’ I asked.

‘Well, it’s a surprisingly busy little building, isn’t it?’ said Morley. ‘A charming young lady from the first floor escorted us up. I think she said her name was Desiree?’

‘I think you’ll find her name is probably not Desiree,’ said Miriam, looking knowingly at me.

‘Sorry?’ said Morley.

‘“That one may smile, and smile, and be a villain – At least I am sure it may be so in Denmark.”’

‘Hamlet?’ said Morley. ‘I can’t see the relevance, my dear.’

‘Denmark. Street,’ said Miriam.

‘Anyway,’ I said.

‘Yes, quite,’ said Morley. ‘Anyway. No time to lose, eh, Sefton? Another book to write.’

‘Sorry, did we finish the last one?’

‘Yes, we did,’ said Miriam.

‘Westmorland,’ said Morley. ‘Almost finished.’

‘In your absence,’ said Miriam.

‘Few tweaks, few i’s to dot and some t’s to cross, but we should have it done by the end of next week, Miriam, shouldn’t we?’

‘I would have thought so, Father, yes.’

‘So, ready for the printers and into the shops by the end of October, I would have thought. Excelsior!’

‘Right,’ I said.

Morley was publishing books almost faster than I could read them. I’d been in his employ since early September, working on The County Guides, and we’d already covered Norfolk, Devon and Westmorland. I’d travelled more widely in England within a month than I had in the previous twenty-six years of my pre-Morley existence.

‘You’ll be thrilled to hear, Sefton, that our next county is Essex,’ said Miriam.

‘Essex?’

‘That’s right,’ said Morley. ‘When you think of Essex, Sefton, what do you think of?’

‘When I think of Essex.’ When I think of Essex? It was not a place I had ever given a first – let alone a second – thought to. ‘When I think of Essex I think of …’ I thought of Willy Mann asking if I’d like to work for Mr Klein on some project.

‘Oysters!’ said Morley. ‘Correct! And cockles, sprats, whitebait, flounder, dab, plaice, sole, eels, halibut, turbot, brill—’

‘Yes, Father, we get the picture.’

‘Lobster, haddock, whiting, herring, pike, perch, chub—’

‘Yes, Father.’

‘Gudgeon, roach, tench—’

‘Father!’

‘Winkles. But above all the Ostreaedulis! The English native!’

‘Sorry? The English native …?’