По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

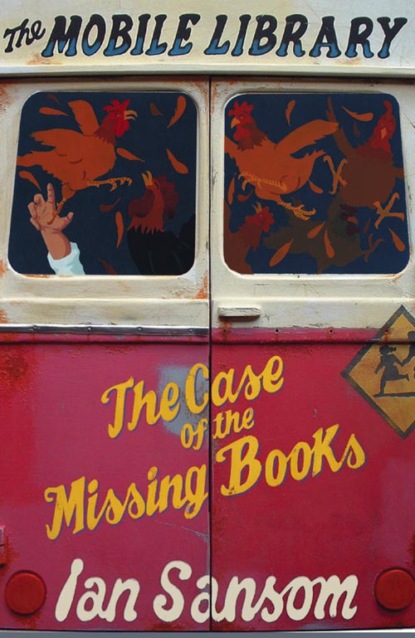

The Case of the Missing Books

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Israel started fiddling with the ropes. ‘These are tight knots. I’m not sure if I can—’

‘Quit your gurnin’ and get on with it,’ advised Ted.

So Israel did.

‘Now. Pull,’ commanded Ted eventually, and he started pulling, and Israel started pulling, and ‘Pull!’ commanded Ted again, and Israel did again, and ‘You’re as weak as water,’ shouted Ted, and ‘Pull!’ again and suddenly the whole big damp dirty tarpaulin came off in a storm of dust and bird and chicken shit, right on top of Israel, who lost his balance and fell back onto the filthy dust and bird – and chicken-shit floor.

‘Aaggh!’

‘What?’ said Ted. There was a muffled sound from under the tarpaulin. ‘You there, you big galoot?’ More muffled sounds. Ted lifted up the heavy tarpaulin and helped Israel out and onto his feet: he was covered, head to foot, in grey dust and black and white and bright green bird and chicken shit.

‘Aaggh,’ said Israel.

‘There she is,’ said Ted.

‘Aaggh,’ said Israel, rubbing his eyes.

The van came into focus. He could just make out what looked like the remains of a bus in a faded, rusting cream and red livery: there were rust patches as big as your fist, and what looked like mushrooms growing around the windscreen.

Ted was down on his knees, examining the wheel arches and the paintwork.

‘Aye,’ he said to himself, lost in rapture. ‘Aye, aye.’ Having eventually circled the bus and patted it fondly, as though calming a beast, he stood back. ‘Well?’

‘Well,’ agreed Israel.

‘Well?’ said Ted. ‘What do you think?’

‘Erm. It looks like a bit like a…bus,’ said Israel. ‘Except without windows.’

‘You’re not wrong, Sherlock Holmes,’ said Ted. ‘It’s a Bedford. Built on a VAM bus chassis. Beautiful, isn’t she?’

‘Beautiful’ was not quite the word that Israel had in mind: the words he had in mind were more like ‘write-off’, ‘wreck’, ‘filthy dirty’, ‘yuck’, and ‘I want to get out of here and go home.’

‘You are joking me, are you?’ he said.

‘Joking?’ said Ted.

‘This is not the mobile library,’ said Israel.

‘That she is.’

‘But we can’t possibly drive that…thing. It’s a wreck.’

‘Lick of paint, be as good as new,’ said Ted.

Israel put his hand into a rust hole.

‘Come on,’ he said.

‘And a bit of bodywork,’ admitted Ted.

And then there was the soft sound of something heavy and metal falling onto the ground and Ted got down on his hands and knees and looked underneath the vehicle.

‘And some spot-welding,’ he admitted. ‘But she’s no jum.’

‘I see,’ said Israel, who had absolutely no idea what a jum was. He was up on tiptoe trying to peer into the bus’s dark interior.

Ted produced some keys from his pocket and weighed them heavily in his hand, as if they were precious jewels. He then placed them ceremonially in Israel’s hands.

‘Over to you, then,’ said Ted.

‘No, really,’ said Israel.

‘She’s all yours,’ said Ted.

‘No. I—’

‘Take. The keys,’ said Ted insistently.

‘Right,’ said Israel.

‘So,’ said Ted.

‘Well,’ said Israel, hesitating and trying to think of something appropriately moving to say. He couldn’t. ‘It’s an—’

‘Get on with it.’

‘Right.’

He went to open the door on the driver’s side of the mobile library, but there was no door on the driver’s side.

‘Oh,’ said Israel.

‘Other side,’ said Ted.

Israel went round to the right side and placed the key in the lock, turned, and nothing happened. He looked helplessly at Ted.

‘Jiggle her,’ said Ted.

Israel jiggled as best he could, but he was getting nowhere. He let Ted have a jiggle. That was no good either.

‘Ach,’ said Ted, examining the keys. ‘Rust.’

‘Oh well. Another time maybe.’

‘Not at all,’ said Ted, pointing up at the top of the van. ‘Skylight.’

‘What about it?’